One of Fullfrontal’s constant endeavors in the last few years has been to gather and share information about Hayao Miyazaki’s next film, The Boy and the Heron, from early information about its production to a review published on the day of its release in Japan. It was therefore a matter of course for us to interview some of the film’s staff. We turned to one of our acquaintances, legendary animator Toshiyuki Inoue.

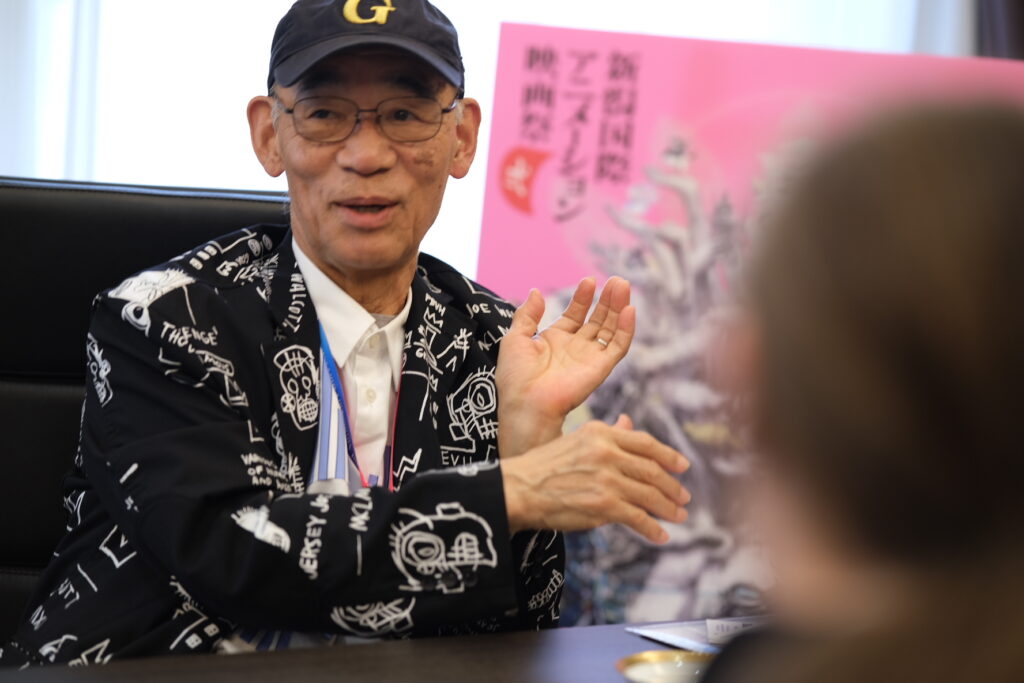

Inoue, nicknamed “the perfect animator” by some, is widely considered to be both one of the greatest craftsmen and one of the most knowledgeable people in animation history in Japan. He served as a key artist behind some of Japanese animation’s greatest masterpieces: Akira, Ghost in the Shell, Millennium Actress, Dennō Coil, The Wolf Children… But, aside from Kiki’s Delivery Service, he remarkably worked very little with Hayao Miyazaki before The Boy and the Heron.

We therefore took the occasion of a long talk with Inoue to discuss his history and relationship with Miyazaki, the production and art of The Boy and the Heron, and much more.

This interview is available in Japanese. 日本語版はこちらです

This article would not have been possible without the help of our patrons! If you like what you read, please support us on Ko-Fi!

“I can’t even pretend to rival Miyazaki”

In our interview from a year and a half ago, you said that The Boy and the Heron strikes the perfect balance between Takeshi Honda’s [1] taste and Ghibli’s animation. I couldn’t imagine what this could mean back then, but now I understand how right you were.

Toshiyuki Inoue: Right, they’re well mixed together, aren’t they? People who don’t know what it looks like may imagine that Honda’s sensibility would come out more because he’s the animation director, but Miyazaki and Ghibli’s own flavor are perfectly blended in.

You’re right. It’s a beautiful movie, thank you very much for your hard work.

Toshiyuki Inoue: Thanks to you. It wasn’t easy work. (laughs)

Actually, before talking about How Do You Live, I’d like to ask about Kiki’s Delivery Service, since it was your first collaboration with Miyazaki. First, how did you arrive on the production? Was Sunao Katabuchi [2] still the director at that stage?

Toshiyuki Inoue: He was.

So did you participate in the location scouting trip to Europe?

Toshiyuki Inoue: I didn’t. I was invited on Kiki towards the end of Akira’s production. Multiple animators from Ghibli helped out on the film, among which Shinji Otsuka. He told me about this project they had for a new film made by the young staff from the studio. Miyazaki would just write the script, Katabuchi would be the director and Katsuya Kondō[3] the animation director. That’s how he invited me to join. I had heard pretty scary things about how it was working with Miyazaki, so if he had been the director maybe I wouldn’t have agreed to work on it. Since the director was Katabuchi, I took Otsuka’s offer and he got me the job at Ghibli. But I didn’t go to the studio before the get-together of all the staff, where everybody introduces themselves and so on. I went to that meeting, and here was Miyazaki, who welcomed everybody saying, “Nice to meet you. I’m Hayao Miyazaki, the director of this film.”

I hadn’t heard anything about what happened, so I was quite surprised – it kind of felt like I had been tricked. It was too late to back out, so I remained on the movie. But I remained a bit puzzled about it the entire time.

I believe you’ve always been a fan of Miyazaki’s, why were you scared to work with him?

Toshiyuki Inoue: I had heard quite a few scary stories. A lot of acquaintances had worked on Nausicaä, Laputa and Totoro before that, so I knew how scary he could be when he got angry – I had heard stories of people being fired mid-production, things like that.

How was it actually?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Not as scary as I had imagined. He’d only rarely scream in the studio. But he did get angry. I’d sometimes be called to some separate room and lectured alongside Kōji Morimoto and Masaaki Endō. It felt like being in school all over again.

Was it educational, then?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Rather than that, I realized my lack of ability. I became painfully aware that I couldn’t get to the level Miyazaki wanted.

There are lots of reasons for that, but the first is that I’m not fit for Ghibli’s style. I can’t draw Miyazaki’s characters. Just before Kiki, I was on Akira, where I tried my hardest to make characters look three-dimensional from every possible angle, and by the end of it, I had more-or-less mastered that skill. But Ghibli’s characters are different: volume and accuracy aren’t the most important, because they’re more flexible, more cartoony. In terms of movement as well, Miyazaki doesn’t look for anatomical truth. Rather, he wants to express emotions and feelings as directly as possible. But I had been pulled in by Akira just previously, and I became incapable of not approaching things logically.

In fact, I’d say that Akira was much closer to my own personality. That logical approach and all that… I’m not that smart overall, but I tend to consider things very analytically, and it’s on Akira that I realized that it was what suited me best in terms of work. But on the other hand, I couldn’t understand Ghibli’s way of doing things.

But Kiki’s layouts are particularly complex, aren’t they? Doesn’t it require an analytical approach like yours to pull such layouts off?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Of course, you need to be analytical to some extent to draw correct perspectives and such, but Miyazaki doesn’t want the perspectives to be too correct. Besides, he expected people to know about all kinds of other stuff, which wasn’t my case. For instance, Kiki’s setting looks like Europe, and I didn’t know anything about European architecture back then. Since I didn’t particularly look into the subject, obviously I couldn’t draw much. It might be exaggerating to say that it feels like a failure on my part, but even though I could do so much on Akira, I suddenly faced all the things I couldn’t do: not being able to realize what Miyazaki wanted, not knowing about Europe or history or architecture… Whereas Miyazaki knows so much about all of that.

So he also expected animators to be as knowledgeable as him, is that it?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Exactly. If something I drew wasn’t exactly right, he’d notice it and call me out, asking why I didn’t know about how it actually was. I was told the ships I drew were no better than a kid’s drawings, that I probably didn’t even know about how a ship was built. (Bitter laugh) And of course I didn’t know any of that, so I had nothing to answer: I just realized how much I lacked to be able to draw as many things as I wanted, and it was very painful.

“It was worth it”

With that in mind, would you say that for you, The Boy and the Heron is like Kiki’s return match?

Toshiyuki Inoue: I’ve always wished for a return match or a way to redeem myself. But even if I say that, I know I can’t even pretend to rival Miyazaki. I just can’t win. He’s extremely smart and learned, and on top of that, as an animator he always transcends common sense: he’s so talented that I know very well there’s nothing I can do against it. The more I learn about him, the more I realize I’ll never be on that level.

Thinking about it, if it hadn’t been Honda inviting me on The Boy and the Heron, I probably wouldn’t have participated. He really insisted, you know, so I decided to join him. Now I’m happy I took his offer: it was worth it, and I really like the film as a whole. I saw it three times, once at the staff screening and twice more at the theater. I’d like to go another time.

I understand that very well, I think I’ve seen it 4 or 5 times already. (laughs)

Toshiyuki Inoue: That’s impressive. (laughs)

Speaking hypothetically, if Isao Takahata were still alive, would you think you’d be a better fit to work with him?

Toshiyuki Inoue: It would be different with Takahata. His approach was very logical, he really thought about how things would move in reality… So I think I could have met his expectations to some degree.

And personally, would you say you’re satisfied with your own work this time?

Toshiyuki Inoue: I feel like I got better since Kiki. That was over 30 years ago, and I’ve seen all of Ghibli’s works in that meantime. Back then, I was locked into the mindset I had gotten from Akira, but as time passed my way of thinking has changed: I think I’ve become perhaps a bit better at creating that thing in animated movement that doesn’t completely boil down to logic. And finally, Miyazaki’s been getting old and can’t draw as much as he did: when I joined, you could really feel it. His drawings aren’t as powerful, he’s not as fast, he can’t focus for a long time anymore. So I feel like maybe my contributions served the film better this time.

From time to time during the film, the movement felt very much like Miyazaki’s own. Did he do key animation himself or anything in spite of what you’re saying?

Toshiyuki Inoue: I believe that in some interview, Toshio Suzuki said that Miyazaki just focused on the storyboard and didn’t review the animation, but that’s not quite what happened. Miyazaki probably intended to review all of the film by himself. But as age was starting to catch up, he couldn’t focus as much anymore, so he’d give the most difficult shots to Honda. He also wasn’t as strict as before: he would approve drawings that wouldn’t have passed before just because he didn’t have the strength to correct them. But in many of those cases, Honda wasn’t sold and completely redrew some of these drawings.

Regarding the designs, they feel very close to Honda’s sensibility. How involved was he in the designing process?

Toshiyuki Inoue: For the designs, Miyazaki made some original designs, like illustrations of the characters, which were then copied exactly as is. I should have brought that with me today… (laughs) Honda really traced Miyazaki’s drawings just as they were, so I’d say that 90% of the designs come from Miyazaki. In that sense, it wasn’t different from Miyazaki’s other movies. Honda’s own flavor comes through the mob and background characters.

What about Natsuko? She really doesn’t look like a Miyazaki character…

Toshiyuki Inoue: Ah, yes, you’re right on target. The reference sheet is entirely Honda’s. After all, Miyazaki isn’t very good at designing adult women, so when he tries to draw women with lipstick or who just look mature, it ends up looking weird. That’s what happened in Porco Rosso, it felt like there was something missing – if it had been someone like Katsuya Kondō, he could have done better. It’s not like there’s nobody in Ghibli able to draw realistic, adult women who fit in the films, but since the original design is always Miyazaki’s…

What actually happened until now is that Miyazaki himself would review the key animation and that the animation director just traced and cleaned up his corrections, so they’d inevitably get caught up in his style. But I believe that this time, Honda was thinking the same thing I just told you. So he just copied Miyazaki’s drawings for Mahito, the old men and women, but in Natsuko’s case, he made his own changes.

What about Mahito’s father? Is he 100% Miyazaki as well?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Probably. Honda only changed Natsuko. He first did some changes on the reference sheets, and then some more while he was correcting the drawings, so it completely became his character. Once they’re in the other world, when Mahito finds Natsuko and all the papers fly around, that scene was completely redrawn by Honda, and he changed the style all over again. Even if Miyazaki sort of did his own reference drawings, as the animation and story were progressing, the characters progressively changed as well. Miyazaki is particularly good at adopting different styles that perfectly fit each individual scene, but on top of that, you have to add the fact that Honda tends to stop following his own designs when he works. It was the same on Dennō Coil [4] and Millennium Actress [5], the way characters look progressively changes as the production goes on.

This isn’t just something that Honda does: it happens a lot in Japan. When the same person does both the character designs and the animation direction, they often end up changing things on their own. It’s the same with Hiroyuki Okiura[6], for instance. He had done the designs for Run, Melos, but the finished film looks nothing like the reference he drew. That left the animators pretty surprised… Of course, there are people who do corrections following what they drew in the first place, but when the character designer and animation director are the same person, some seem to think that it’s alright to change things as it goes. (Wry laugh)

By the way, there’s no “character design” credit on Miyazaki’s movies, and this time as well. Do you have any idea of why that is?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Now that you say it… Isn’t there any even on Nausicaä?

(Checks credits) Looks like not.

Toshiyuki Inoue: None, huh. I wonder why. (laughs) That’s pretty strange indeed. If I were to try to explain, it might go like this. Certainly, the original draft is Miyzaki’s, but the ones to actually draw the reference sheets are the animation directors of each film. Then, when he does his rough corrections, Miyazaki does them in his style and brings yet more changes to the designs. These are cleaned up by the animation directors and get referenced instead of the actual reference sheets. And of course, if the key drawings are good enough, that’ll influence everybody else, so looking at the final picture, it’s hard to tell for sure who’s the individual who designed what.

Aah, I get it, thank you very much.

“The Boy and the Heron is very much Honda’s film”

Coming back to what we were saying earlier, of course it’s a single film, but it feels like it switches between multiple styles. Sometimes it looks like it’s following in The Wind Rises’ footsteps, sometimes it looks like Evangelion, and some other times it’s closer to something designed by Masashi Andō[7] or Hiroyuki Okiura… What do you think about this?

Toshiyuki Inoue: You’re right, I completely agree with you.

I actually just joined the production in the latter half. You could say I joined two times: first I did around 25 cuts, left to work on Extraterrestrial Boys and Girls and then came back for 20 cuts on the last scene. I only worked on the second half, so I don’t know how things went on the first half – the film was made in the same order as the story, first the A part, then the B part, then the C part, then the D part, then the E part… That was to follow Miyazaki’s pace as he progressively completed the storyboard. I would say that when the A part was done, Miyazaki was still comparatively young and full of strength, so he could put all of his energy into correcting the animation. Honda wasn’t used to Miyazaki’s way of doing things either, so he mostly still just cleaned up Miyazaki’s corrections. So in terms of drawings and acting, the first half of the story is closer to what Miyazaki’s been doing until now. That would be why you feel like it resembles The Wind Rises. However, the scene when Natsuko first appears, from Mahito’s arrival at the station to the point when they enter the manor, is Honda’s animation. I don’t mean that he redrew someone else’s animation or that he worked on top of Miyazaki’s corrections: that’s his own key animation all the way through. Because of that, it probably feels very much like Honda and particularly like Evangelion…

After that is Katsuya Kondō’s part, right?

Toshiyuki Inoue: I see you’re well-informed. (laughs)

I just wanted to make sure. (laughs) But it’s precisely the A part which I found the least Miyazaki-like.

Toshiyuki Inoue: Ooh, is that so? That’s a bit unexpected. But now that you say it, there’s both Honda and Ohira’s[8] scenes, so I see where you’re coming from.

It was particularly the opening scene, even before Ohira’s part. In the very first shots where you first see Mahito, he’s got a big, aquiline nose. That’s very different from what you usually see in Japanese animation, even Miyazaki works, so I was really surprised.

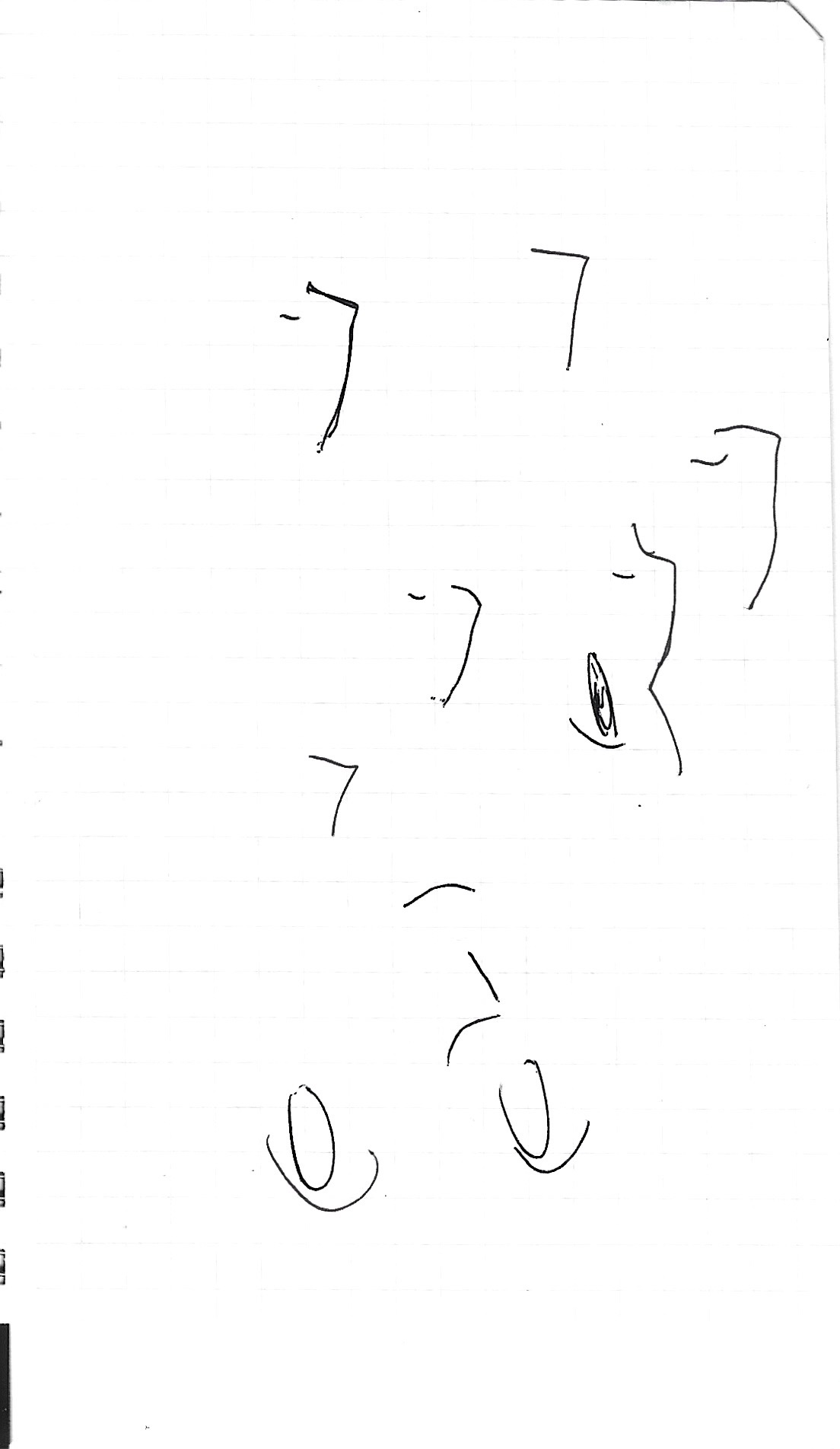

Toshiyuki Inoue: You’re right, the shape of noses is pretty different from what you usually see in Miyazaki’s work. The noses became like that mid-way, and they’re pretty noticeable. Honda told me Miyazaki told him to do so, but I don’t know the details, he just said it was his advice or something. But the noses don’t look like this in the reference sheets. [starts sketching a few faces]

Usually, anime characters have pretty big eyes and the nose is pretty small, almost invisible – like this one on top. They’re all like that, aren’t they? Perhaps Miyazaki doesn’t like these kinds of faces, and that’s what he might have told Honda. Mahito has a nose like that, Natsuko as well, Himi as well… That’s how they look from the side.

Mahito’s father also has a nose like that.

Toshiyuki Inoue: The father is the most extreme case. I just said maybe Miyazaki didn’t want usual anime noses, especially for adults, and in Mahito’s case he probably wanted him to look like his father and gave him a nose like that. However, I think the aquiline nose doesn’t fit Himi well, she’s supposed to be a little girl after all… In any case, I don’t know if Honda took a liking to aquiline noses all of a sudden, or if Miyazaki just tended to approve the drawings more easily if the noses were like that… But you’re saying they’re already like this in the A part?

Especially the cut when Mahito’s waking up. That really struck me.

Toshiyuki Inoue: Is that right… That didn’t strike me as much.

Because there was no promotion or anything, I really focused on the animation in a different way. As soon as the movie started, I got like, “ah, this is what they’re going for?” and went from surprise to surprise. That made it really interesting. But anyways, after that nose thing comes Shin’ya Ohira’s scene, right? He wasn’t even corrected…

Toshiyuki Inoue: He was, for Mahito’s face. It’s still necessary to correct Ohira a bit to preserve the exact intent he’s going for. Also, if you just leave Ohira’s drawings as they are, it’s hard for the in-betweeners to follow up, so you need to focus the lines a little bit more. But the mob characters or the firemen are probably Ohira’s raw drawings.

You just said you weren’t there yet at this point in the production, but do you have any idea if the choice to not do corrections was Miyazaki’s or Honda’s?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Rather than someone’s individual decision, I’d say they probably both agreed on it. They must have discussed it and decided that it was the best possible approach. Miyazaki himself knows Ohira’s work very well.

But in Miyazaki’s previous films, Ohira’s animation was corrected, though I don’t know if that’s Miyazaki or the animation director…

Toshiyuki Inoue: That’s true. When Ohira’s scenes take place in more normal settings, there might be no other choice than to correct him. But in this case, you can’t really tell whether the scene is real or a dream. You see Mahito waking up, but it doesn’t really feel real, and everytime that happens it’s Ohira’s animation. For instance, when Mahito arrives at the manor, falls asleep and sees his mother in a dream – it looks just like the opening scene. Or when Mahito looks at the entrance of the house, waiting for his father from the top of the stairs, falls asleep and then the image of his mother appears. Mahito himself was drawn by Honda, but the drawings of the mother are Ohira’s. Miyazaki’s probably aware that this kind of scene is what fits Ohira the best and that you don’t need to correct him too much in such cases, so that would be why he decided to have him.

The truth is, when Honda asked Ohira to join, he was a bit worried. On a Miyazaki film, the characters have to remain on-model to some degree, so Honda was worried that he’d have to correct Ohira. He asked Miyazaki if it was ok to call for him because he was so worried, but Miyazaki was perfectly alright with it. He convinced Honda, and I believe he suggested using Ohira on these special scenes so that he could go all the way without getting in the way of the rest of the film. In fact, I’d say Miyazaki drew the storyboard for the opening scene with the assumption that Ohira would animate it. I mean, can you imagine anyone else than Ohira on it? (laughs)

Regarding that, do you have any idea of how the animation casting went about? For instance, how were you assigned your scenes?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Hm, I don’t know about that… But Miyazaki doesn’t really work with people he doesn’t know, so Honda or someone else would have introduced them, showing some of their work to Miyazaki. If he knew them Honda would say what kind of people they were, what they were good or bad at… Nowadays you can watch things pretty easily, so he would have shown him some of their work and then let him decide.

Looking at the credits, it feels like we’re back to the golden age of the realist school[9]. Everybody’s there except Mitsuo Iso and Hiroyuki Okiura. (laughs)

Toshiyuki Inoue: Shinji Hashimoto[10] isn’t there, though.

Ah, that’s right.

Toshiyuki Inoue: I believe he only worked on Spirited Away… Miyazaki and him weren’t a good fit for each other, apparently. I don’t think Miyazaki quite realized the extent of Hashimoto’s ability… It’s a real shame, since Hashimoto is one of the few whose talent stands up to Ohira’s.

Coming back to what we were saying earlier, even beyond the designs, one of the strong points of The Boy and the Heron is how you can feel the individuality of each animator. In a way, would you say that what happened between Honda and Miyazaki is a sort of repeat of what happened between Kazuo Komatsubara and Miyazaki back on Nausicaä?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Actually, I love Nausicaä. It’s admittedly pretty common in Japanese animation, but I like it when each animator’s quirks are visible in the final film. Perhaps that’s because I’m an animator myself. Of course it’s probably not the best when the style completely changes every time a new animator comes in, but you can strike a certain balance between the two – and I’m always happy to see it realized. That’s the case for Nausicaä, with for instance Takashi Nakamura’s scenes, or Yoshinori Kanada’s… For instance Nakamura’s scene at the beginning, when the Ohmu comes out: it’s unmistakably his work.

So even though I was just one of the members of the staff on The Boy and the Heron and can’t see it as normal viewers do, it makes me happy to hear that people saw it that way. Though I must say that Honda redrew a lot of scenes, so his own style probably comes out the most. But Honda has a very wide range, so sometimes it feels very realist-school, sometimes it’s more cartoony, sometimes it looks like any other Ghibli work… Precisely because of that diversity, I would say that The Boy and the Heron is very much Honda’s film.

“I feel bad about it now”

Honda was the animation director, of course, but did you receive any instructions from Miyazaki himself? Regarding how to animate certain things, for instance.

Toshiyuki Inoue: Not that much, actually. It would have been easier if he had explained some things in more detail or done roughs, of course, but he’s the type to leave it to the animators. Moreover, if he had been as healthy as before, he would have used the original animation as a springboard as he always does. He uses it as a template, and then progressively adds his own thing: that’s how he works. Everybody tries to do things as Miyazaki would, but he rarely approves drawings, and rather uses them as the ground upon which he can build when doing corrections. But I actually think it would be more efficient if he just did all the rough keys himself instead of redrawing everything after the fact…

And what about the storyboard?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Actually, I brought it here! Do you want to see it? (takes the storyboard out)

Wait, what? (laughs)

Toshiyuki Inoue: I’m not quite sure about The Wind Rises, but Miyazaki’s sight is getting a bit bad, so the drawings are rougher than in his previous works.

(Flipping through the storyboard) Oh, it’s colored!

Toshiyuki Inoue: The beginning is. Then he gave up.

(Flipping through the station scene) You were right, Natsuko looks totally different in the storyboard…

Toshiyuki Inoue: She looks more like a character from Millenium Actress in the end, doesn’t she?

Yes, in particular that scene later on when Mahito finds Natsuko again in the other world… The way bodies are drawn, it’s very volumetric, I thought that looked like a Satoshi Kon film. At first I wasn’t sure if it was you, Honda or Masashi Andō…

Toshiyuki Inoue: Yes, it looks like a lot of people thought that, but it’s all Honda’s corrections. Or rather than corrections, you could call that his own key animation.

The original animator was someone from Ghibli, but the chemistry between Ghibli’s animators and Honda wasn’t ideal. Honda’s lines are sharper and he’s going for something realistic, whereas Ghibli people will go for round, expressive things – maybe a bit too round sometimes… That’s not Honda’s thing at all, so… That doesn’t apply to Katsuya Kondō and Akihiko Yamashita[11], though. He has a lot of respect for them, so he almost didn’t correct Yamashita’s drawings, whereas in Kondō’s case, he did do corrections but always in such a way that Kondō’s art would stay visible. It was different for the other Ghibli animators: when their drawings arrived to him, he’d tend to correct them. Miyazaki knows their work well, so he’d let them do what they were good at and approve their drawings, but then Honda looked at them and increasingly corrected them… or something like that.

I see.

Toshiyuki Inoue: About the scene with Mahito and Natsuko, it’s really complex, so first he drew Mahito, even the parts that are covered by the paper, and then all the papers that stick to him on another sheet.

Is that all on 1s?

Toshiyuki Inoue: That’s right, most shots are.

In your case, what timing do you usually go with?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Animating on 1s is a bit too much work so I usually go with 2s or 3s. If you’re on 1s, you have to draw the keys in such a way that the in-betweener can follow. On 2s or 3s, it’s possible to not use in-betweens and control the movement with just the key frames. But if you’re on 1s and need the in-betweener to be able to do their work, you have to specify everything: which drawing, how, where it should be… you have to lay everything out and that’s a bit annoying. If I did the in-betweens myself, it would be a different story, but it’s too much work to do it all yourself on 1s. That’s what Ohira does, though. (laughs)

Back to key animators, there’s one scene I’m really curious about, because I think it’s one of the best in the entire film: when the heron calls out Mahito and the frogs climb on his body and everything…

Toshiyuki Inoue: That’s Akihiko Yamashita’s animation. I’ve heard he did at least one fourth of the film, something like 400 cuts by himself, and he also helped out with animation supervision.

Since you’re so fast, I thought you’d have done at least as much, but…

Toshiyuki Inoue: No, I really just helped out at the end, I didn’t do anything more than 50 cuts.

You did the finale, right? When Mahito and Natsuko come out of the other world, and the birds fly out…

Toshiyuki Inoue: Right, that’s me.

Is that all?

Toshiyuki Inoue: No, I did 2 scenes. The finale is the second one: when they all come back to the real world for good, the tower collapses, the birds come out, until the heron says his farewell. And the first one… (flips through the storyboard) is when Mahito and Himi come out in the real world for the first time, Mahito’s father comes running and fights against the parakeets…

Animating animals is said to be the hardest of all, how was it to do the parakeets? There’s so many all around…

Toshiyuki Inoue: (laughs) That was difficult! I had never drawn any pelicans or parakeets, and there are so many coming out, it wasn’t easy. (laughs) In another studio, you could do it digitally and do copy-paste, but Miyazaki doesn’t really get how that works, so he told me to draw it all by hand. (Wry laugh)

How many birds are there? (laughs)

Toshiyuki Inoue: I don’t know! (laughs) A lot!

Animating the transformation mustn’t have been easy either…

Toshiyuki Inoue: It was pretty hard… The heron’s transformation as well.

Reminds me of that rotation, when the background turns all black, the camera turns around Mahito… that was really great.

Toshiyuki Inoue: Thank you very much. My part went until that shot.

And after that?

Toshiyuki Inoue: After that is Yamashita, and then the last scene is Katsuya Kondō.

So he did all the scenes inside the manor?

Toshiyuki Inoue: He did a lot, but not all. For instance, the first scene with the old women is by Shinji Otsuka. Kondō drew a lot of scenes in the other world as well.

It looks like everybody drew a lot of shots. Something striking about your scenes is the acting of Mahito’s father. It’s realistic, but also exaggerated… His emotions are always so intense.

Toshiyuki Inoue: That was on Miyazaki’s request. What I drew at first was quieter, more realistic, but Miyazaki advised me, told me it wasn’t like that… He didn’t correct my drawings, but I changed them based on what he said, and Honda didn’t correct them that much either.

For the birds, did you use any reference? Photos or videos or anything?

Toshiyuki Inoue: I had never drawn pelicans before, so I used a lot of photos, and also videos of birds flying. What I realized is that pelicans have very long feathers. They’re very long and thin – that really struck me, but in the end I think the feathers in my cuts are too long, and I feel a bit bad about it now.

“Miyazaki’s method is really a reference”

This is a very weird question, but every time birds come out on screen, you can also see their droppings everywhere…

Toshiyuki Inoue: Yes, I drew some of that. (laughs)

Is it even indicated in the storyboard?

Toshiyuki Inoue: It is, it is!

Do you have any idea of the reason? Does Miyazaki hate birds or something?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Why is that. (laughs) That’s just what birds do, I guess. That’s probably how Miyazaki sees birds: if you don’t see their droppings, it’s not really birds or something…

As you can see, the storyboard actually isn’t that detailed about the acting or movement of the characters. Nowadays, the acting is often laid out in utmost detail so that the animators don’t get lost. A lot of things are specified in the storyboard, to the point that it sometimes feels like animators just have to make clean copies of it. But in Miyazaki’s case, he leaves animators free for the layout, and it’s only at the key animation stage that he starts actually considering how things move and how characters should act.

We talked about this before, but it’s only when he checks the key animation that Miyazaki rethinks everything and does his corrections. He adds all the things that aren’t in the storyboard at that point. But on the other hand, all the rest, like the compositions and camera angles and movements, are already perfectly decided in the storyboard. Same thing for the special effects and the photography. It was already the case at the time of Cagliostro and Nausicaä. I think someone expressed it that way: it’s like he does the storyboard after the movie is already finished.

Which is to say, the film and storyboard are so identical that people who see one of his storyboards for the first time often feel that the film isn’t done as is written in the storyboard, but rather that it’s a storyboard made after the film just to be sold. Usually, the storyboard isn’t really the final cut: lots of changes are made at the layout stage – when you draw the layout or the key frames, you might realize that something is missing and add shots, or instead cut some out. But in Miyazaki’s case, there’s no room for improvement, there’s nothing to change or to add. Even Miyazaki himself doesn’t change his own storyboards.

Talking of storyboards, you’ve worked a lot with Satoshi Kon, whose storyboards are legendarily detailed. What would you say is the difference?

Toshiyuki Inoue: (Thinks) Similarly, once Kon completed the storyboard, there were nearly no changes, but… it’s hard to say.

Kon wasn’t an animator at first, so was his approach different?

Toshiyuki Inoue: They’re different. The reason Kon’s storyboards are so detailed is that his pictures would be enlarged and used as layouts. Miyazaki’s storyboards aren’t used in that way, and he doesn’t focus that much on the perspective or the small details of each image at that stage.

What about photography? Does Miyazaki control it closely in his storyboards?

Toshiyuki Inoue: He does, he absolutely does. Nowadays, photography is digital so you can do lots of things regarding camerawork and compositing, but in the analog days, Miyazaki came up with lots of new techniques. Photography back then had a lot of constraints, so you couldn’t exactly do what you wanted. There was a limited set of techniques, like double exposure, superimposition, depth-of-field… Miyazaki was really good at making something out of those limitations, how to combine techniques or use them individually. He was always thinking about what process would be both the most efficient and best-looking.

He had been in charge of layouts for some time, so I suppose that led him to take an interest in all that…

Toshiyuki Inoue: Yes, considering how many layouts he drew in his time, that must have been a very important experience. He’s always been very talented, but his work as a layout artist only developed that talent. He knew how to come up with camerawork and effects efficiently and create exactly the kind of images he wanted. He was really gifted. Even when you watch them today, Miyazaki’s analog-era works are incredibly well-crafted – they haven’t aged one bit. Miyazaki’s method is really a reference.

So with that in mind, I’d say that the big difference between Kon and Miyazaki’s storyboards is that Kon didn’t want to depend on the animators. He made it so that each shot wouldn’t be too difficult to understand and animate. Whereas Miyazaki’s boards require good animators: they’re very complicated and the movement can be very complex – too much for weak animators.

“The style changed naturally as the tone changes”

Coming back to The Boy and the Heron… I was curious about the heron. Looking at real herons, they’re actually pretty small and look kind of fragile, but the one in the film is…

Toshiyuki Inoue: It’s pretty big.

Exactly! I know you didn’t work on the A part, but do you have anything to say on that? In terms of how it’s designed, or animated…

Toshiyuki Inoue: If I had been drawing it, I’d probably have done it more realistically, studying how herons actually look and fly. But Miyazaki doesn’t look at reference or anything, you see.

Personally, I’d have loved to draw more of the heron. Actually, I love drawing birds and animals. I don’t really like drawing humans. (laughs) That’s because I’m not very good at drawing faces.

In the second half, including in your scenes, the heron becomes really grotesque – you don’t know if he’s supposed to be scary or ridiculous.

Toshiyuki Inoue: That’s the word. Whereas he’s really scary at first.

It’s not just the heron, but the film’s first and second half are pretty different, aren’t they? Do you think the approach to animation changed as well?

Toshiyuki Inoue: I don’t think there were any explicit instructions, at least. It probably just changed naturally as the tone changes: the first half is rather serious, scary and quiet… so Honda’s realistic style is a perfect fit, and I think it’s perfect that way. As it goes, the tone becomes more comical, especially with the heron, so the animation changes as well. It becomes more like one of Miyazaki’s old so-called ‘cartoon films’, closer to Future Boy Conan. But it’s not like Miyazaki said it should become like that, or Honda explicitly told us to make it cartoony. You get it just by reading the storyboard: the heron becomes more comical, so animating him very realistically would feel weird.

Talking about that, doesn’t the scene when all the parakeets have their big procession and Mahito and the heron try to sneak in remind you of Cagliostro?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Ah, that scene is by Masahi Andō. It looks like Honda and Miyazaki almost didn’t correct him…

The shots just afterwards with all the stairs in the tower don’t look simple…

Toshiyuki Inoue: That’s also Andō. It wasn’t easy as you said. In the end, he drew quite a lot.

So I guess most of the comical scenes with the parakeets are Mr. Andō’s?

Toshiyuki Inoue: You could say that, in that part of the film at least. From the point where the parakeet king first appears…

Regarding the production, it appears to have been quite long, so does that mean the schedule or deadlines were less intense than usual?

Toshiyuki Inoue: I guess they were. It did feel like we had time. Back at the time of Kiki’s Delivery Service, Miyazaki would arrive at the studio at 10AM and work until midnight, and you’d better not leave before he did, so it was pretty intense. This time, he’d arrive sometime in the morning and leave at 8PM, so thanks to that we could work on reasonable hours. However, Honda brought his work back home, so it mustn’t have been as easy for him. And even for us animators, even though we had time, the contents of the film were pretty difficult to animate, so it remained very challenging. I think it was particularly the case for Yamashita. He’s got a strong sense of responsibility, so he probably thought that the movie wouldn’t be over if he didn’t do his best on all the many scenes he was in charge of.

Was everybody working in Ghibli?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Most animators were, though some people worked from home. In my case, I only came to the studio on Mondays and Thursdays.

Is there one shot or scene that you’re particularly fond of?

Toshiyuki Inoue: (thinks) In terms of impact within the entire film, I’d say Honda’s scene between Mahito and Natsuko and all the bits of paper flying around… But perhaps it goes too hard there. (laughs) It’s like the movie’s already reached its end by that point. It’s a bit like in Laputa, when Pazu comes to save Sheeta… After that the rest of the film kind of feels like a letdown. (laughs) That’s how it felt for Laputa, and it was a bit similar here. In terms of visuals, story, music, everything, that scene feels like the real climax.

But in the end I love all of it.

“You don’t need to understand everything about movies sometimes”

I’m sorry about the difficult question. (laughs)

Toshiyuki Inoue: What about your friends living in Japan? Did they like it?

I think everybody liked it, but it’s a pretty difficult film so they all said they weren’t sure what it’s supposed to be about. Though I believe Japanese have the same reaction.

Toshiyuki Inoue: Yes, it might be difficult to understand but it’s a good film overall. There might be some strange parts in the second half, but it raises some truly interesting questions, and I think it’s what makes the film so good. I don’t think it’s possible to understand all of it. Miyazaki himself said he doesn’t understand it all, so it’s not made to be understood.

Yes, it feels like he put the things he doesn’t understand himself into the film.

Toshiyuki Inoue: And it’s good that way. You don’t need to understand everything about movies sometimes.

How did the rest of the staff feel about it?

Toshiyuki Inoue: I didn’t really have occasions to ask what the rest of the staff feels, since I didn’t spend that much time at the studio. However, Honda really seems to have liked The Boy and the Heron. He’s fallen in love with it. He can be rather harsh and it’s really rare for him to praise even things he worked on. With that in mind, it’s kind of exceptional for him to like that one.

What are your projects from now on?

Toshiyuki Inoue: I have lots of work coming up, but I’m already 62, so I have maybe 10 years left at best? Miyazaki’s in his 80s, so maybe you can make that 20 years, but my eyesight is getting bad and doing animation is becoming increasingly hard. Compared to other people my age, I’m still doing good, but I’m not a director or anything. Ultimately, I’m going to remain an individual animator until the end.

Why didn’t you ever want to do at least some storyboarding?

Toshiyuki Inoue: If I were as good as Miyazaki, I’d like to do it, but… I just can’t, that’s how it is. I can’t draw anything as detailed as Satoshi Kon, I can’t draw like Okiura or Hosoda… And I can’t win against Miyazaki. So I have no reason to even try.

Is that for the same reason that you’ve almost never done any character designs?

Toshiyuki Inoue: I don’t really like designing that much, and I’m not that good at it. I don’t really have any images or ideas that I’d like to turn into designs, so I have more fun just doing key animation. Moreover, what happens if there are no animators? If everybody starts doing designs or direction, nobody’s there left to animate. I’d rather like it for the good animators to remain animators. Recently, all the young artists start doing episode direction or storyboards and stop animating. I think it’s a real shame – even though the number of young talents has been going up, they’re all quitting animation…

The number of talents isn’t only going up in Japan – even in France, there’s a lot of fantastic things coming out, I never run out of things to look forward to.

Do you watch a lot of foreign animation?

Toshiyuki Inoue: I do. Strangely, Japanese animators rarely have an interest in foreign works, but I like watching Disney works, both old and new, European or Chinese animation… I want to see all the good things regardless of the technique, whether it’s 2D, 3D or stop-motion. But it never ends: there’s so much good stuff you’re never done.

I feel that. (laughs)

Toshiyuki Inoue: On top of that, foreigners upload a lot of animated clips on the web, just watching that is more than enough. For instance there’s been all the clips from One Piece recently, the young people are doing some fantastic things… But I only watch those by bits.

By the way, I think I’m speaking for all overseas fans by saying this: thank you for always helping out identifying the animators behind certain sequences on Twitter.

Toshiyuki Inoue: The scope of my knowledge is limited, but if I find mistakes within that, I correct them. That’s one of the good points of the Internet: people who were actually there and know how things happen can share the correct information and leave it for passionate researchers such as you. That’s why I try not to write about the things I don’t know or I’m not sure about. So that the things that Toshiyuki Inoue took responsibility to certify might keep some value online.

I understand very well. Thank you very much for this and today.

Words fail us to express how thankful we are to Mr. Inoue for his time and kindness.

Interview by Matteo Watzky and Dimitri Seraki.

Transcript by Karin Comrade.

Translation, introduction and notes by Matteo Watzky.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

Notes

[1] Takeshi Honda (1968 – ). The Boy and the Heron’s animation director. Former Gainax animator, nicknamed “Master”. He has been one of the best character animators at Gainax since his work on Aim for the Top! Gunbuster. He is also praised for his character designs, especially on Dennō Coil and the Rebuild of Evangelion series.

[2] Sunao Katabuchi (1960-). Director who worked in Nippon Animation, Telecom, Studio Ghibli and Madhouse, he is now the lead creative in studio Contrail. Famous for his movies Mai Mai Miracle, Arete Hime and In This Corner of the World, he is considered to be Isao Takahata’s disciple and closest follower. He was initially supposed to direct Kiki’s Delivery Service but was relegated to assistant direction for unknown reasons.

[3] Katsuya Kondō (1963-). Animator, character designer. A pillar of studio Ghibli since nearly its creation, he has contributed to many of the studio’s movies as either animator, animation director or character designer. He is particularly famous for being character designer on Kiki’s Delivery Service and animation director on Ponyo on the Cliff by the Sea.

[4] Dennō Coil. 2007 TV series, Madhouse, dir. Mitsuo Iso. The first director work of legendary animator Mitsuo Iso, it is generally regarded as one of the best TV anime of its decade. Supported by a staff of star animators from the realist school, it was pioneering in many ways, including promoting the work of young animators and its use of digital technology.

[5] Millennium Actress. 2001 movie, Madhouse, dir. Satoshi Kon. Satoshi Kon’s second film, retracing the life and career of a fictional actress. Featuring Takeshi Honda’s character designs and animation direction, it is lauded for its realistic animation.

[6] Hiroyuki Okiura (1966 – ). Originally from studio Anime R, Okiura became one of the greatest talents in the realist movement after he participated in Akira. After moving from effects and mecha to character animation, Okiura has established himself as one of the greatest draftsmen in Japan. He is famous for his steadfast adherence to photorealism, sometimes leading to the misconception that his work is rotoscoped. A close collaborator of Mamoru Oshii, he has moved on to directing movies that still bear the standard of realism: Jin-Roh, A Letter to Momo…

[7] Masashi Andō (1969-). Animator. Former member of Studio Ghibli, he became one of the closest collaborators of director Satoshi Kon following his departure. One of the foremost animation directors and character designers in Japan, he is scheduled to work on Sunao Katabuchi’s next film, The Mourning Children.

[8] Shin’ya Ohira (1966-). Animator. One of the most radical artists in Japanese animation, known for his extremely detailed and expressionist animation. Initially one of the leaders of the realist school in the 1990’s, his work now verges on the experimental. He has been a regular presence on Hayao Miyazaki films since Porco Rosso.

[9] Realist school. Group of animators formed in the late 1980s, just before and after Akira. Although styles and approaches largely differ between members, this “school” partly rewrote anime’s visual vocabulary throughout the 1990s, bringing it towards more detailed layouts and a more accurate reproduction of human anatomy and movement. Representative works include Akira, Ghost in the Shell and Jin-Roh; foremost members include Toshiyuki Inoue, Hiroyuki Okiura, Mitsuo Iso, Shinji Hashimoto…

[10] Shinji Hashimoto (1967-). Animator, character designer. One of Shin’ya Ohira’s closest friends since the early 1990s, he was one of the major members of the realist school of animation. While his style is similar to Ohira’s in its use of deformation, Hashimoto is also famous for his adaptability to all kinds of styles and has been a regular presence in studio Ghibli’s works.

[11] Akihiko Yamashita (1966-). Animator, character designer. Best known for his character designs on Giant Robo, he has become a regular presence on Ghibli and Ghibli-related works since his first collaboration with Miyazaki on Spirited Away. After becoming animation director on Howl’s Moving Castle, he became one of the most important artists in Ghibli throughout the 2010’s.

If you want to learn more about the topic, you might be interested in:

The following are affiliate links

By clicking on the following links and placing an order, fullfrontal.moe earns a small amount on your order, which helps support the website.

This article would not have been possible without the help of our patrons! If you like what you read, please support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Oshi no Ko & (Mis)Communication – Short Interview with Aka Akasaka and Mengo Yokoyari

The Oshi no Ko manga, which recently ended its publication, was created through the association of two successful authors, Aka Akasaka, mangaka of the hit love comedy Kaguya-sama: Love Is War, and Mengo Yokoyari, creator of Scum's Wish. During their visit at the...

Ideon is the Ego’s death – Yoshiyuki Tomino Interview [Niigata International Animation Film Festival 2024]

Yoshiyuki Tomino is, without any doubt, one of the most famous and important directors in anime history. Not just one of the creators of Gundam, he is an incredibly prolific creator whose work impacted both robot anime and science-fiction in general. It was during...

“Film festivals are about meetings and discoveries” – Interview with Tarô Maki, Niigata International Animation Film Festival General Producer

As the representative director of planning company Genco, Tarô Maki has been a major figure in the Japanese animation industry for decades. This is due in no part to his role as a producer on some of anime’s greatest successes, notably in the theaters, with films...

I could read Inoue for hours without getting bored

This was really insightful, I always get curious about how animators who pass by Ghibli think about their work once it’s over.

i have read many articles about this latest movie but omg THIS goes into SO MUCH depths compared to all the rest. Man miyazaki sounds like a boss from hell from these anecdotes : angry screams, making all work until midnight… not allowing modern techniques . I feel sorry for the animators xD

Make sure to check out the website next week, more like this is coming! 🙂