Takeshi Honda is a highly respected animator amongst anime fans, known for his exceptional work on several popular anime series, including Hideaki Anno’s Nadia: The Secret of the Blue Water and Neon Genesis Evangelion, and Satoshi Kon’s Perfect Blue, and Millenium Actress. Over the years, he has become a household name among anime fans and is regarded as one of the best animators in Japan.

However, his role as animation director on Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron brought him into the mainstream spotlight, introducing him to a new audience that may not have been familiar with his work.

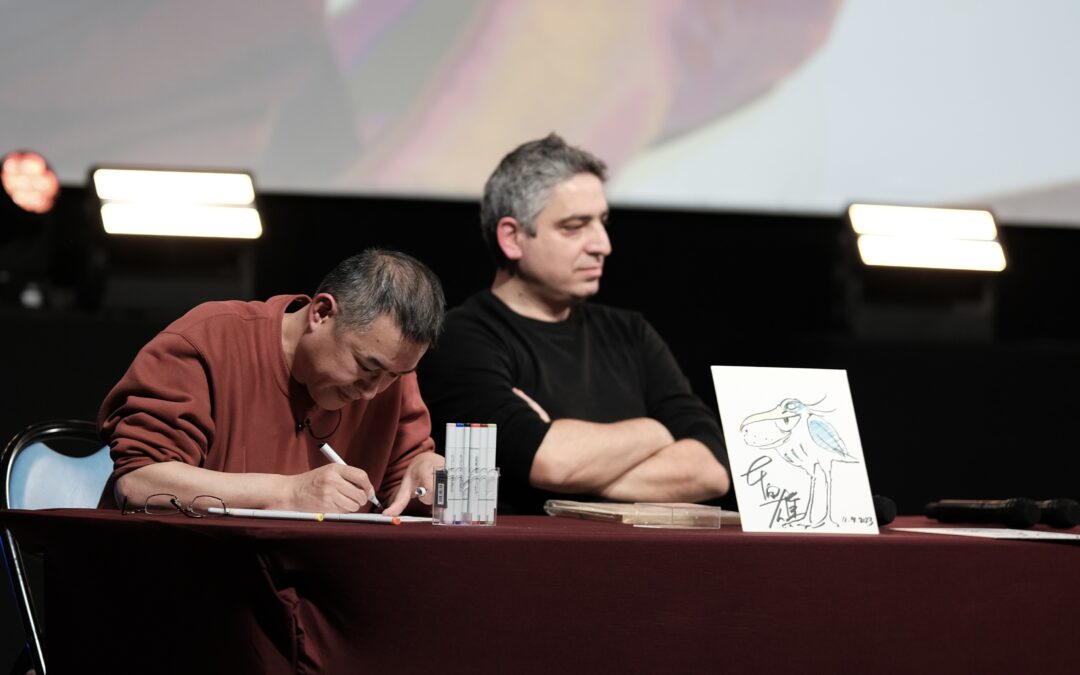

Last month, Mr. Honda made an appearance at the Art to Play convention in Nantes, France – his first overseas appearance since the 2016 London Comic Con, where he gave a panel that provided a unique insight into his career. He spoke candidly about his experiences and shared anecdotes from some of the most notable anime works of the past 50 years.

Being able to listen to the history of half a century of anime, since Takeshi Honda worked on some of the most important works of that period, was a treat, although many of them had already been covered in the past by Japanese publications. We decided to share his words and anecdotes with you by compiling them in this short summary.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

Takeshi Honda opened the panel by briefly sharing his opinion on the city of Nantes. He spent the night in the historical part of town and thought that Hayao Miyazaki would’ve really enjoyed visiting.

When he was young, Honda didn’t really know what he wanted to work in, but he had always loved to draw, inspired by anime such as Mazinger Z. When Takeshi Honda grew older, after watching Future Boy Conan at around 10, he realized the potential of animation as an art form and started pursuing it. When Honda was 16, his older brother entered university. His brother asked him to lend a hand with the opening animation his anime club did for the local convention, Uracon. He remembered drawing tanks and one of the girl characters with her clothes torn up but noted he only did a few cuts.

This experience is what made him aim to go further in this craft. Once he graduated from High School, he convinced his parents to let him move from Ishikawa prefecture to Tokyo to pursue a career in animation. His first professional experiences were in small, now-defunct studios such as Thunder Pro and Atelier Giga. But after the latter closed down, he went freelance and eventually joined Gainax. He answered their offer after realizing this was where Yoshiyuki Sadamoto worked, whose work on Royal Space Force: Wings of Honneamise he admired.

Gunbuster was his first assignment at Gainax. Aim for the Top! was a sort of parody of the groundbreaking shoujo sports manga Aim for the Ace. He then naturally thought he would be working on something just like the original manga, but as the series advanced, he realized things were completely different and getting increasingly dramatic! At first, he was not so fond of the parodic nature of the show but gradually enjoyed the dramatic tone, reminding him of what he loved in Honneamise. At that moment, he understood the talent of his seniors, Anno and Sadamoto.

After that, Nadia was Gainax’s first long-running series. It was a hard time! The staff wasn’t ready for the workload and the pace of respecting the deadlines set by the TV broadcast. Takeshi Honda also mentioned the chaos provoked by director Anno’s changing opinions, especially his decision to go back to a serious story and in-house production for the last few episodes of the series after the comical and controversial “Island Arc”. To this day, Honda is still dissatisfied with his work on the series, mulling over how much better it’d have been under better conditions and with his current skills.

Nadia was a tough experience, but it was nowhere close to Honda’s next and nearly final work at Gainax, Otaku no Video. He described it as “painful”: no time, no funding, a story he wasn’t interested in… and a problematic relationship with the producer. Conflict over his wages for his work on the series is what led him to quit Gainax and join studio AIC.

At AIC, he worked on Ah! My Goddess. It was a fun experience on some points since he was with some acquaintances, notably the director and animation director with whom he was friends. But “just animating girls” wasn’t Honda’s thing and left him frustrated – it’s not a good memory for him even today. And, just as he feared that he would have to work on projects like that for all his life, he was called back to Gainax to work on the sequel of the film he loved so much, Wings of Honneamise: Uru in Blue. Directed by Hideaki Anno, written by Hiroyuki Yamaga, and designed by Yoshiyuki Sadamoto, it was a dream project, ambitious enough to bring him back to the studio he had left.

However, Uru in Blue was never completed, mainly because Honneamise’s sponsor decided to leave Gainax hanging and did not put out funds for this projected sequel. Honda also noted that it was during Uru’s preproduction he first met with Satoshi Kon, who was supposed to contribute layouts to the film. Honda already knew about Kon and was a big fan of his. He also had the chance to be sitting just next to him, so he thought up a strategy to break the ice. He left one of Kon’s manga open on his desk, which tickled Kon’s curiosity. When he finally asked, the young Honda revealed how much he liked his work and begged him to sign the book, which he did. This was the beginning of a long relationship between them.

However, with Uru in Blue abandoned, Gainax was left in a dire financial situation. They had to produce something new to get back on their feet, and that’s when the Evangelion project started. Little did they know at the time it would end up being quite a costly production as well! Tight scheduling and budgeting were in order, and Gainax hell started again. A big part of the problem had to do with the director, Hideaki Anno: he didn’t know where he wanted to go, didn’t deliver scripts or storyboards in time, and just left the rest of the team wondering what they were even supposed to be aiming for. Delays kept accumulating, and that’s how the last two episodes ended up the way they did.

The series’ success was a real surprise for everyone, but it allowed Gainax to retry their chances, particularly to redo episodes 25 and 26. It was the first time Honda worked on a feature film, and it wasn’t exactly a great experience – once again, because of Anno! The advancement of the screenplay and storyboard went so slowly that the animation team only had two months before the theatrical release to work on the actual animation production – all the staff was at their limit and ready to go wild with anger. So, as an emergency measure, only half of the projected film ended up being made and would be shown after re-edited recap footage: this was Death and Rebirth. The staff was given more time to produce a “complete edition”, The End of Evangelion.

This was, however, the limit for Honda. He was on the verge of quitting the industry altogether and left Gainax a second time. He then started collaborating with other directors than Anno, such as Hiroyuki Okiura on Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade or Satoshi Kon on Perfect Blue, both of which were great experiences.

Satoshi Kon liked Honda’s work on Perfect Blue and personally called him on his next film, Millennium Actress. Kon was a master in many more ways than one. Honda was very impressed by his ability to merge quality and quantity: he was faster than most animators. Getting to work alongside him was a life-changing experience, and there, Honda met with many other talents with whom he would keep collaborating in the years to come. It felt like a fresh start, which made him want to step up his game.

The projects Honda worked on afterward were more diverse: the one he remembered the most was Kôji Morimoto’s short on Animatrix. Next was Mamoru Oshii’s Innocence. It was a difficult project, as Honda was asked to animate some unconventional scenes. Oshii’s instructions were always either vague or abstract, and it was tough for Honda to know what to do with the layouts he received.

Innocence was followed by a pretty hard experience: Dennô Coil, with director Mitsuo Iso. According to Honda, so much happened on that series that you could write an entire book about it. They ran out of time, as usual, but Honda also got into fights with Iso, who debuted as a director on the series. Thankfully, it seems like they’re on better terms nowadays. But, at the time, things were so tense that Honda left mid-way – he felt like he could do so thanks to the presence of Toshiyuki Inoue, who took over his duties as chief animation director and ensured that the series would retain the same amount of quality.

Honda then went on to work for Oshii’s Sky Crawlers, on which he had a great time. Right after that was Shin Evangelion, for which he came back to work for Anno again. He didn’t expect to get called back by Anno after he had left Gainax the way he did, but things just have a way of happening. The conditions were better this time, but as usual, the director was just too slow… In Honda’s opinion, Anno’s main issue is that he never aims for a goal while writing his stories. He often starts with great ideas but falls short when trying to tie all of them together. There was no clear throughline to the new series, which is why, according to Honda, its production took so much time. This uncertainty led him to drop from the last Shin Evangelion film production, where he was supposed to work as chief animation director.

Indeed, as the production of the last film started, another contender stepped into Honda’s ring: Hayao Miyazaki expressed his interest in hiring him. Miyazaki knew Takeshi Honda had accepted to work with Anno, but it didn’t matter. He had a movie idea with Honda’s name in the credits… And when you get called by Ghibli, you pick up the phone. Of course, Honda wanted to accept, but his previous engagement was important to him. He answered that he’d need a bit more time to smooth things over, but the then-77-year-old Miyazaki shot back at him, saying, “No one in the Miyazaki family ever lived past 80. There’s no time left!” For Honda, being able to work with Miyazaki is the dream of any animator: the possibility of missing his chance convinced him to drop Shin Evangelion.

The Boy and the Heron ended up being a 7-years affair. Honda got used to tight deadlines throughout his career, so this was a whole new kind of experience. Seven years of being able to create one satisfying work of art was a true breath of fresh air.

Going from Anno to Miyazaki ended up being an eye-opening experience. Both are somewhat difficult to work under, but not for the same reasons. In Miyazaki’s case, the main difficulty is following up on his expectations and managing to work with his storyboards, which can be very difficult. It’s almost like a challenge from one artist to another, but Honda didn’t feel like it was a problem: what might be a hard time for other animators is his idea of a good challenge. He’d choose this over Anno’s time constraints any day of the week.

Honda then commented on his collaboration with Miyazaki before The Boy and the Heron, the Ghibli Museum short film Boro the Caterpillar. It was originally planned to be in full 3DCG, but as can be expected, Miyazaki hated the first results. So he called for the help of some 2D animators, among whom Honda himself served as animation director. Miyazaki did all of the layouts of the first half, which is animated in 3DCG, while Honda animated most of the second half in 2D. But Miyazaki was still frustrated with the 3D, saying, “What’s on the screen isn’t what I drew!” He particularly complained about the amount of detail in the animation and the timing, creating something too clean and fluid. There was something of a contest between the 2D and 3D animators – for instance, Honda remembered that he was sometimes faster than the 3D animators on some scenes. So he decided to animate by himself some of the scenes that were supposed to be in 3D but weren’t completed yet! So, while the entire short was meant to be animated in 3D, the result is more 50-50. This 15-minute film took about a year to make.

Takeshi Honda then went back to talking about The Boy and the Heron and discussed the challenge of adapting his style to Miyazaki’s. He noted that he didn’t particularly try to do something “new” or “original” but instead worked hard to imitate Miyazaki’s style. In that regard, the hardest thing was not changing his style too much during the 7-year production. For Honda, there’s a clear difference between the film’s first and second half, the first being closer to Miyazaki’s style and the second to his own – he started getting more comfortable and found his own footing. He thought this wouldn’t sit too well with the director, but found out that he didn’t really care that much when characters weren’t exactly on model.

On top of the visual style, Honda was asked about the references to Miyazaki’s previous works in The Boy and the Heron. Maybe they mattered to Miyazaki, but he never really talked about it. For Honda, it’s more that Miyazaki has a certain style and certain things he wants to draw, and he’ll just naturally gravitate towards these things. Continuing on the topic of Miyazaki, Honda discussed his directing style and, notably, the way he works closely with the background and coloring staff: he would often make notes and define the colors himself, as this is something he particularly cares about.

Then, Honda noted that Miyazaki likes it when things are done the way he wants: he closely controls the pictures down to the most minor details – Honda particularly noted Miyazaki’s insistence on the shapes of eyes and noses. But he also remarked that Miyazaki got too tired at some point to redraw everything and left most of the corrections to Honda by the second half of the film. Honda gave the example of creases in clothing: Miyazaki tends not to draw them in detail, whereas Honda loves them. As it went, Honda got the opportunity to add more and more creases and could put his own style in the film.

Then, Honda went on to discuss character emotions and character acting. He noted that Mahito is quite an unusual character: his psychology and representation of it are uncommon. The acting always had to be subtle and nuanced and avoid the exaggerated expressions Miyazaki had tended to use in his previous films. All of this happens to be Honda’s specialty, and he puts a lot of effort into it.

Besides the humans, there are also all the animals in the film. Honda told an anecdote related to that. Approximately one year after the production began, Miyazaki and the staff made a company trip to Tochigi prefecture. Many activities were available, and Honda chose to visit the local zoo – where he ended up going alone! There was sadly no heron, but Honda could observe a real pelican and was impressed by the size of its beak and the width of the movement of its wings. He recorded it all and used it as reference on the film.

He added that every day, Miyazaki goes for a walk in a park where there is a heron. But this very heron doesn’t move a single bit; he just stands here without doing anything. So every day, Miyazaki returned to the studio saying, “It doesn’t want to move…”.

Finally, after humans and animals, Honda discussed natural elements. One of the things that fascinates him the most is the movement of the sea and how to reproduce it in animation. He has some painful memories of failing to animate the sea satisfyingly in a previous production, so this time, he challenged himself to draw the sea much better than he did before.

Ultimately, Honda concluded by saying that this movie is not like the previous ones at all. Even though Toshio Suzuki told everyone at Ghibli to let Miyazaki do everything he wanted, the director himself probably considered it as his last piece of work and had quite a specific mindset. Maybe 2 or 3 rewatches are necessary to fully understand it, but it’s very different from what the audience knows.

Translation and summary by Florian Abbas, Loïc André, and Matteo Watzky.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Benoît Chieux, a career in French animation [Carrefour du Cinéma d’Animation 2023]

Aside from the world-famous Annecy Festival, many smaller animation-related events take place in France over the years. One of the most interesting ones is the Carrefour du Cinéma d’Animation (Crossroads of Animation Film), held in Paris in late November. In 2023,...

Do anime events have room for creators? – Interview with Koji Takeuchi

The Annecy International Animation Film Festival is a place of many little pleasures, and one of them is to meet with Kouji Takeuchi, a pillar of the anime industry, and learn a little bit more of Studio Telecom's lore, which you can read more about in our previous...

Directing Mushishi and other spiraling stories – Hiroshi Nagahama and Uki Satake [Panels at Japan Expo Orléans 2023]

Last October, director Hiroshi Nagahama (Mushishi, The Reflection) and voice actress Uki Satake (QT in Space Dandy) were invited to Japan Expo Orléans, an event of a much smaller scale than the main event they organized in Paris. I was offered to host two of his...

Recent Comments