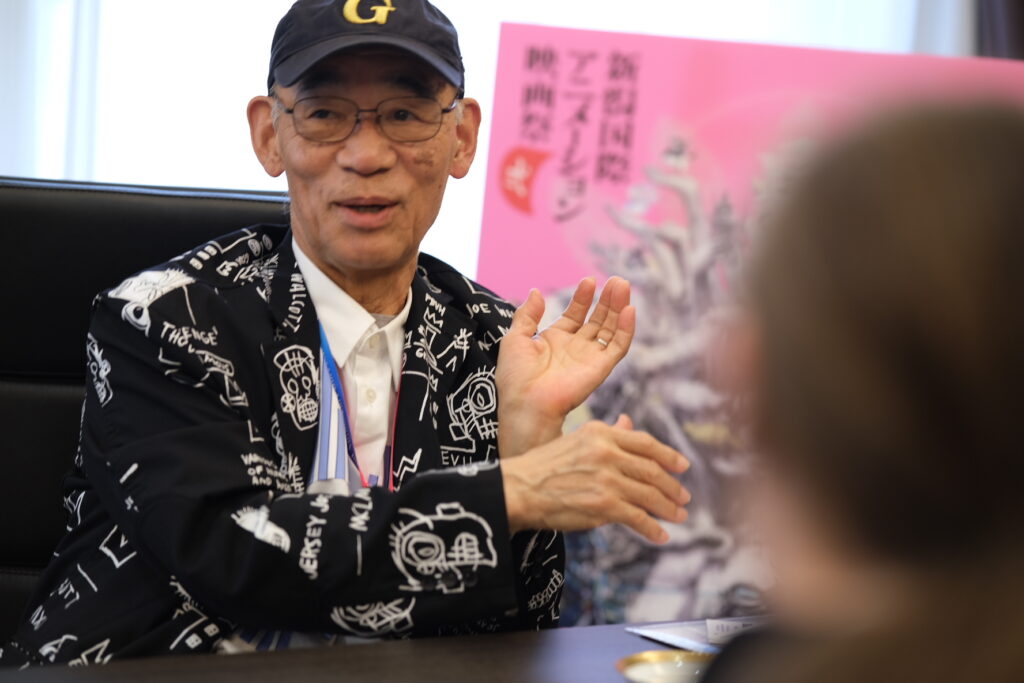

Toshiyuki Inoue is one of the most important animators in Japan. Nicknamed “the perfect animator” for his proficiency, ability, and range of expression going from cartoony deformation to absolute photorealism, Inoue is a legendary artist. Beginning his career in 1982, he was quickly promoted to character design and animation direction on Gu Gu Ganmo. His work on Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honneamise, Akira, and Kiki’s Delivery Service propelled him to fame in the following years. He became one of the leading artists in the “realist” movement that developed after Akira and worked on many iconic productions such as Ghost in the Shell, Jin-Roh, A Tree of Palme, and Millennium Actress.

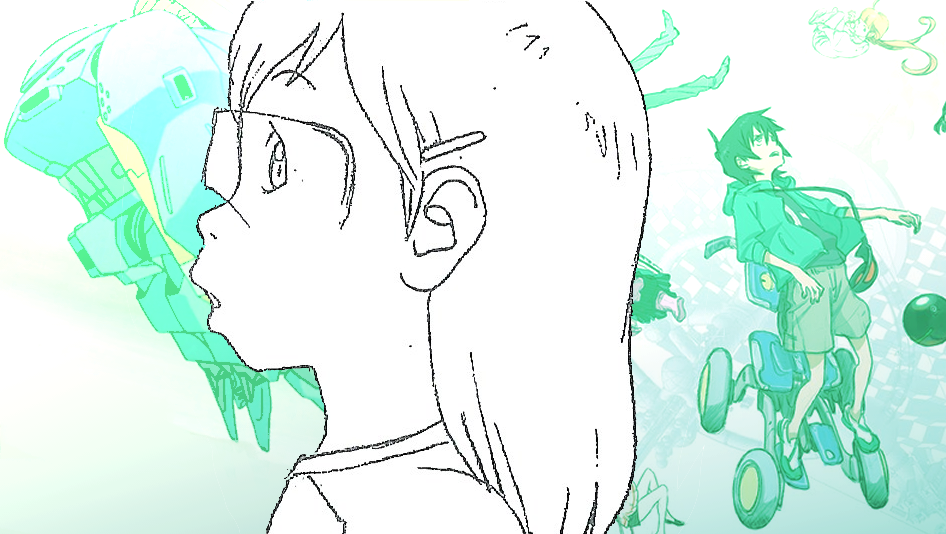

Most recently, Inoue has taken on even more important jobs that attest to his stature in the anime industry: in 2018, he was Main Animator on the movie Maquia: When the Promised Flower Blooms, and is also credited as such on the series The Orbital Children, available on Netflix at the time of publication of this interview.

The Orbital Children is the work of one of Inoue’s closest friends, legendary animator Mitsuo Iso. For this interview, we asked Inoue about his relationship with Iso, their collaboration on the latter’s 2007 series Dennou Coil, and their latest work together, The Orbital Children.

Even though he is busy working on Hayao Miyazaki’s upcoming movie, How Do You Live? M. Inoue was kind enough to grant us some of his precious time and answer our questions. He had the following to say about his current work on Director Miyazaki’s movie:

“I am working on How Do You Live? right now. Most cuts left to do are mine. I’m a bit late because I left Ghibli mid-production to work on The Orbital Children… When I’m done, the key animation should be complete.

As you may know, the animation director is Takeshi Honda, who’s doing a wonderful job. I can’t wait to see the movie when it’s finished: it’s a great balance between Ghibli’s animation and Honda’s unique sensibilities.”

This article is available in Japanese. 日本語版はこちら

We are happy to bring you this interview, but we can only do so with your help!

Help us finance future interviews by supporting us!

“Iso pursued the essence of movement.”

We would like to discuss your relationship with Mitsuo Iso for this interview. The work that made Iso famous was his sequences on War in the Pocket [1], especially as an effects and mecha animator. Did you see it back then? What was your impression of Iso and his work?

Toshiyuki Inoue: I watched War in Pocket at Satoru Utsunomiya’s [2] house when it came out. He invited me to come to watch the first episode of Gosenzosama Banbanzai [3], and I went in the middle of the night. That’s when he showed me the beginning of War in the Pocket, which Iso animated. In a bitter tone, he said, “some impressive new guy has appeared…” He has a strong sense of rivalry!

But I suppose Utsunomiya watched it because he wanted to know more about Iso’s ability as he was supposed to participate in Gosenzosama Banbanzai #04.

By the way, Gosenzosama Banbanzai #01 hadn’t come out yet: Utsunomiya showed me his exclusive copy. You may be familiar with it from the anime Shirobako [4], but I’ll explain just in case. The “shirobako” (white box) is a video copy in a white case of a work distributed to the staff before it is released or broadcast. Today, it’s not a tape anymore but rather DVDs or Blu-rays, but we still call them a “white box.”

Alongside animators like Takashi Nakamura [5] and Satoru Utsunomiya, you were strongly influenced by Hayao Miyazaki, Yasuo Otsuka, and the artists from the studio Telecom Animation Film [6]. Do you think Iso received the same influence?

Toshiyuki Inoue: I don’t know if they influenced Iso, but it’s hard to think that anyone in our generation wasn’t. In fact, I think the way he animates water, like the surface of the sea, is clearly inspired by Tôei movies such as Animal Treasure Island: for example, look at the first episode of Final Fantasy – Legend of the Crystals, or the sixth episode of the Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure OVA.

I’ve repeatedly heard him say that he liked Yoshinobu Inano [7] and Yoichi Akino – I think he only realized later that they were just one person. In the 70s and 80s, Inano was someone who did some very realistic animation. Although Inano’s drawings were “realistic” in terms of “movement,” they weren’t innovative enough to inspire Iso. I think Iso may have acquired his own way of animating by trying to develop a “realistic movement” that was appropriate for Inano’s “realistic drawings.”

You just mentioned Final Fantasy. It’s the 1994 OVA, right? As far as I know, Iso only worked on the second episode… did he work on the first one as well?

Toshiyuki Inoue: As you said, it’s episode 2 – in fact, I don’t think I’ve seen any other episode…

I believe he did all the animation from the point where the young hero gets on his motorcycle until the end. As you may know, I’ve heard that Iso worked on the OVA from a studio in China. He drew the rough key animation (that is the first key animation), and the second key animation must have been done by the Chinese staff. That’s why the number of cuts he was in charge of is unprecedented. On the other hand, for the same reason, some cuts don’t look like his drawings at first glance. Still, I really like it because I think his work on the OVA is wonderful.

How would you define Iso’s style, and how is it different from yours?

Toshiyuki Inoue: We’re completely different! My animation is quite “conservative”: it’s just about making the influences I received cleaner and more polished. When I began animating (and it’s probably still the same now), it was common for animators to practice and learn using a set method for how to make animation drawings. Instead of just getting bored with this, Iso pursued the essence of movement by observing human beings and natural phenomena – and he succeeded in integrating this into his own animated movement.

After Char’s Counterattack and Gosenzosama Banbanzai, Iso worked a lot with Shin’ya Ohira [8]. As someone who worked with both, do you think there are some particular affinities in their way of animating? Or in their personalities?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Maybe they became close at the time of Gosenzosama Banbanzai because they were from the same generation. In fact, after that, there were a lot of disagreements between them. But I think that’s normal: they consider themselves rivals.

As for their style, they both worked on Gosenzosama Banbanzai, and because of that experience, they were very close, for example, on The Hakkenden [9] #01. However, just after that, their paths diverged quite a lot. I believe that, in the beginning, Ohira’s animation was strongly influenced by Iso’s. I directly asked Ohira about that once, and he firmly denied it – but I don’t believe him. I think he refused to admit it because Iso is his rival (bitter laugh).

Both you and Iso collaborated with Mamoru Oshii on multiple works. On Patlabor and Ghost in the Shell, there was a tightly-knit team of “realist” animators around Oshii. Can you talk a bit about the atmosphere that reigned at the time?

Toshiyuki Inoue: At the time, the “realist” generation was around its thirties. By then, we began to have enough experience, and we were able to draw the things we wanted with a certain freedom. However, personally, I couldn’t catch up with the innovative styles of Iso, Ohira, or Osamu Tanabe [10] : I think I remained quite conservative because the only thing I was doing was refining the animation style of the 70s and 80s. But even then, I felt that I could express things that I wasn’t able to express before and to do it on a higher level. For that reason, I’m happy I could work with excellent directors such as Mamoru Oshii or Katsuhiro Otomo.

It was not long after that time that the transition from cel to digital happened. How did you feel about the change?

Toshiyuki Inoue: In Japan, “digitalization” remained confined to finishing (coloring) and photography divisions for a long time. It’s only recently that the animation itself has started to become digital. For that reason, at the time, our work as animators didn’t really change, whereas the difficulties of cel-era photography decreased: things are now more practical.

“He’s a genius that nobody else can imitate.”

You played an essential part in Iso’s TV series Dennou Coil. Could you tell us what your role was in the production?

Toshiyuki Inoue: My credit on Dennou Coil was “chief animation director,” but it was slightly different from the usual work of a chief animation director.

The usual function of a general animation director is to correct all the layouts (i.e., the rough key animation) so that the characters remain consistent throughout. But I only did that for some episodes of Coil: instead, I acted as regular animation director on as many episodes as possible, and I also did key animation. I was also in charge of doing the animation retakes on each episode under the director’s instructions.

At what point did you become involved in the production?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Coil wasn’t made in order, starting with the first episode: the first one to be made was episode 2. I was busy on Paprika at that time, so I had to take two weeks off from it to help on Coil #02. After that, I completed my work on Paprika, and then I joined Coil in earnest. Episodes 1 to 10 of the series were being produced simultaneously (Gainax was in charge of episode 10), and I remember working on episodes 5, then 4, then 9, and so on… Because of that, the production went on quite irregularly.

Sadly, soon after I joined, Takeshi Honda [11] fought with Iso and left. Without him there, the second half of the production was quite an uphill battle. That’s why Yoshimi Itazu [12] and I had to take on the role of chief animation director. (In the credits, Honda kept being mentioned as chief animation director, but in truth, he was absent during the second half of the show)

I remember that Mr. Honda said he would never want to work with Mr. Iso again back then. But do you maybe know how their relationship is on a personal level? Are they on good terms?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Honda told me, “I can talk to Iso normally these days.” So they don’t seem to be fighting anymore. I don’t think I can say they’re on good terms yet.

What kind of director was Iso on Dennou Coil?

Toshiyuki Inoue: On many of the early episodes (such as episodes 1, 3, 4, or 8), he corrected some of the key animation himself (sometimes, he added corrections on top of Honda’s). Still, by the middle of the production, he was too busy with storyboarding and voice recordings to keep doing it. He only gave verbal instructions to the chief animation directors and regular animation directors regarding the corrections he wanted from that point on. That’s how directors usually do it, but I’d have been content with just rough corrections, and I wish that Iso could have done more key animation corrections, just like what Hayao Miyazaki does! He’s a genius that nobody else can imitate, and it’s hard to match the kind of movement and drama that Iso wants with just verbal instructions as a guide.

Do you think Iso’s training as an animator played a part in his direction style? [Editor’s note: This question got lost in translation, and Mr. Inoue understood it as “Do you think Iso training animators plays a part in his direction style?”]

Toshiyuki Inoue: I’m not sure I quite understood your question, but I don’t think him “training animators” had a lot of influence on his “style as a director.” As a fan of Iso’s animation, it’s a bit disappointing…

Sorry for the misunderstanding. What we meant to ask is, since Mr. Iso is also an animator, has it influenced his way of directing? Does he maybe listen to animators’ opinions or have particular requests?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Of course, since he’s an animator, he’s able to correct bad drawings or the ones that don’t match what he wants by himself. In that sense, he followed a “special” method. But as I said, he could only do that for the first few episodes. I would have wanted him to do it all the way through, the Miyazaki way…

He’s an animation genius, so what he expected from the movement was often very specific and hard to communicate. Unfortunately, it was hard for ordinary animators, and even for me, to follow up with that in our drawings.

Besides Iso, you’ve worked a lot with Hiroyuki Okiura [13], who’s also an animator-turned-director. Are his style and direction similar to Iso’s?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Okiura is an even more conservative animator than me, and he doesn’t really like innovative expressions. As a director, what he expects from layouts and animation are “high precision” and “accuracy without any lies.” On Okiura’s works as a director and animation director, I feel that the best you can do is to take care of every single detail. Of course, a sense of detail is important, but you can do better than that.

On the other hand, Iso doesn’t seek such high precision in his animation and sketches. On the contrary, he would rather make a lot of lies in order to create the expression he wants. It seems that being “accurate” is only a secondary concern for him. I agree with him on this.

“The unique and awe-inspiring style of the 70s declined into something not well suited for animation.”

Dennou Coil was a very ambitious production with both veterans and rising stars. Do you think a show like Dennou Coil could still happen today?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Instead of decreasing, the number of anime being produced has only risen in recent years. For that reason, it’s become harder for veterans and talented youngsters to work together, as was the case on Coil. However, I feel that the number of young talents has risen recently, so veterans’ presence isn’t indispensable. I think that young artists have enough ability to make great productions on their own. In fact, this may already be happening.

Thinking about it now, I believe that the young artists who worked on Coil (such as Kiyotaka Oshiyama [14], Yoshimi Itazu, or Akira Honma [15]) were different from today’s generation: they worked fast, were mentally tough, and had strength. During the second half of the production, there wasn’t anything to worry about, even in the most intense moments. I believe it’s thanks to them that we could do it.

Mitsuo Iso has been working on The Orbital Children for over ten years. When did you first hear about it? How long have you been involved in the project yourself?

Toshiyuki Inoue: I forgot the details, but I believe the first time I heard about The Orbital Children was two years ago?

I think that at this point, the show’s scenario was finished. As I started, I was still working on Miyazaki’s movie in December 2020, and I drew the key animation to three cuts of the first episode.

Following that, I joined The Orbital Children for real in 2021, until September 2021. After that, I went back to Ghibli, and I am still working there. I should be done in February.

You’re credited as “main animator” on The Orbital Children. What does this mean precisely? Is it similar to your work on Maquia: When the Promised Flower Blooms, where you did most of the layouts yourself?

Toshiyuki Inoue: I got the “main animator” title once the production was done. Because I was involved in every episode on layout and key animation, as well as helping out on animation direction, the director and producer said, “let’s make Inoue Main Animator.” So there’s nothing exceptional behind the credit.

In that sense, it’s similar to my work on Maquia. For that movie, I drew the layouts for around 300 cuts. Among those, I made the key animation for 120 and the roughs for the other 180.

The character designer for The Orbital Children is Kenichi Yoshida [16]. What do you think makes his designs so appealing? How do you feel animating his characters?

Toshiyuki Inoue: Yoshida is probably trying to become something like what Yoshikazu Yasuhiko [17] and Akio Sugino [18] were in the 70s: people who were both animators and genuine “artists” in their own right. In terms of technology, Japanese animation evolved between 1980 and 2000, when the members of our generation became animators. But in that process, I feel that the unique and awe-inspiring style of the 70s declined into something not well suited for animation. Maybe Yoshida felt the same way, which is why he dared to make such unique designs on Eureka Seven and Mobile Suit Gundam: Reconguista in G. For that reason, his character designs are a bit difficult to move and animate. But this tendency was restrained for The Orbital Children…

Our utmost gratitude goes towards Mr. Inoue for his availability and kindness.

Interview by Watzky Matteo and Seraki Dimitri

Translation by Renault Fabrice and Watzky Matteo

Notes

(1) Mobile Suit Gundam 0080: War in the Pocket. 1989 Sunrise OVA, dir. Fumihiko Takayama. Iso’s work on this OVA, especially the Antarctic base attack at the beginning of episode 1, is what made him famous among fellow animators and animation fans. It is also there that Iso first used his signature “full-limited” animation technique, which consists of him not using the services of an in-betweener and gaining full control over the movement by treating all drawings as keyframes.

(2) Satoru Utsunomiya (1959 – ). Freelance animator who quickly became one of the leaders of the realist group after Akira. He is known for his free and expressive movement, which comes out in, among others, the two OVAs he was animation director on in the early 90s: Gosenzosama Banbanzai! and Fly! Peek the Whale.

(3) Gosenzosama Banbanzai! 1989 – 1990 Pierrot OVA, dir. Mamoru Oshii. This OVA is one of the first great masterpieces of the realist school in the post-Akira landscape. Under the animation direction of Satoru Utsunomiya, the animators from Akira came into contact with different, radical artists such as Mitsuo Iso and Shin’ya Ohira. They heralded a new era for animation where dynamic motion, deformation, and realism would no longer be opposites but complementary.

(4) Shirobako. 2014 PA Works TV series, dir. Tsutomu Mizushima. Shirobako tells how anime production happens from the inside from the point of view of a production assistant. Toshiyuki Inoue contributed a famous and spectacular scene in episode 12.

(5) Takashi Nakamura (1955 – ). Originally from Tatsunoko, Nakamura is arguably the leader of the realist school as it developed in the 80s. As a very popular animator and the animation director of Akira, he directly taught or inspired most of the realist group, including Toshiyuki Inoue and Satoru Utsunomiya. He has since then moved on to become a director and is most famous for A Tree of Palme, Fantastic Children, and The Picture Studio.

(6) Telecom Animation Film. Created in 1977, this animation subsidiary of studio Tokyo Movie Shinsha was led for a long time by Yasuo Otsuka, who trained many of its animators. It was used as a pool for new talents by Ghibli throughout the 80s and 90s. Among the most famous Telecom alumni, we find Kazuhide Tomonaga, Satoru Utsunomiya, Sunao Katabuchi, Tatsuyuki Tanaka, Shinji Hashimoto, Shin Itagaki, Yoshiyuki Sadamoto…

(7) Yoshinobu Inano (1953 – ). Animator from studio Bird, currently affiliated with A-1 Pictures. Famous for his collaborations with director Yoshiyuki Tomino and animation director Tomonori Kogawa, he was one of the leading character animators revolving around studio Sunrise in the 80s, on works such as Space Runaway Ideon, Aura Battler Dunbine, or Mobile Suit Gundam: Char’s Counterattack. He has since then moved on to 3DCG animation.

(8) Shin’ya Ohira (1966 – ). Animator in Studio Break, one of the most experimental and radical artists in the Japanese animation industry. Known as an animator favoring expressionism and deformation, he was also one of the most notable artists in the realist movement. He was animation director on some of its most radical works: “The Antique Shop” (part 4 in the Yumemakura Baku Twilight Gekijô anthology OVA) and the Junkers Come Here pilot – to both of which Iso participated.

(9) The Hakkenden. 1990 – 1991 AIC OVA. Another one of the major works of the post-Akira era featured many contributions from the luminaries of the realist movement: Shin’ya Ohira, Takashi Nakamura, Mitsuo Iso, Hiroyuki Okiura, Osamu Tanabe…

(10) Osamu Tanabe (1965 – ). Former Oh! Production & Ghibli animator, known as Isao Takahata’s “right hand” since the late 1990s. As a member of the realist school, he is among the artists who, like Iso, Utsunomiya, and Ohira, favored expressive and sometimes deformed motion rather than strict adherence to photorealism.

(11) Takeshi Honda (1968 – ). Former Gainax animator, nicknamed “Master” (師匠, “shishô“). He has been one of the best character animators at Gainax since his debut on Aim for the Top! Gunbuster. He also was one of the members of the realist school and a close friend of Mitsuo Iso. A renowned animator, he is also hailed for his character designs, especially on Dennou Coil and the Rebuild of Evangelion series.

(12) Yoshimi Itazu (1980 – ). After going through studios Gallop and Madhouse, Itazu became a close collaborator of director Satoshi Kon on Paranoia Agent and was supposed to act as character designer on the latter’s unfinished project Dreaming Machine. His work as animation director on Dennou Coil was particularly well received. He has since then moved to direction on works such as the movie Pigtails and the TV series Welcome to the Ballroom.

(13) Hiroyuki Okiura (1966 – ). Originally from studio Anime R, Okiura became one of the greatest talents in the realist movement after he participated in Akira. After moving from effects and mecha to character animation, Okiura has established himself as one of the greatest draftsmen in Japan. He is famous for his steadfast adherence to photorealism, sometimes leading to the misconception that his work is rotoscoped. A close collaborator of Mamoru Oshii, he has moved on to directing movies that still bear the standard of realism: Jin-Roh, A Letter to Momo…

(14) Kiyotaka Oshiyama (1982 – ). Originally from studio Xebec, Oshiyama’s first significant work was Dennou Coil. After that, he became the representative of a new generation of artists, first on Space Dandy and then on his directorial debut, Flip Flappers. Today, he is especially appreciated for his design work and is expected to do the creature designs on Chainsaw Man.

(15) Akira Honma (?? – ). Freelance animator who, after Dennou Coil, has largely moved on to movies and contributed to some of the most important productions of the last 15 years: Sky Crawlers, A Letter to Momo, Evangelion 3.0, Your Name, The Night is Short Walk on Girl…

(16) Kenichi Yoshida (1969 – ). Ex-Ghibli animator nicknamed “God” (神) by his friends and fans. He is famous for his work with studio Sunrise first as an animator and then as an extremely popular character designer on Overman King Gainer and especially Eureka Seven.

(17) Yoshikazu Yasuhiko (1947 – ). Animator, illustrator, mangaka, director, and character designer well-known for his collaboration with studio Sunrise as the character designer and animation director of Mobile Suit Gundam. There, he revolutionized character design philosophy. He was also an extremely talented animator who set a gold standard for realistic character acting in the 1970s. Today, he is still active as a manga artist and director and plans to release a new movie, Mobile Suit Gundam: Cucuruz Doan’s Island, in 2022.

(18) Akio Sugino (1944 – ). One of the most important character designers of all time, he was one of the founding members of studio Madhouse and is well-known for his collaborations with legendary director Osamu Dezaki. Their most famous works together include Ashita no Joe, Aim for the Ace, Nobody’s Boy Remi, Space Adventure Cobra, Dear Brother, Black Jack… As of 2019, Sugino was still active as an animator.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Oshi no Ko & (Mis)Communication – Short Interview with Aka Akasaka and Mengo Yokoyari

The Oshi no Ko manga, which recently ended its publication, was created through the association of two successful authors, Aka Akasaka, mangaka of the hit love comedy Kaguya-sama: Love Is War, and Mengo Yokoyari, creator of Scum's Wish. During their visit at the...

Ideon is the Ego’s death – Yoshiyuki Tomino Interview [Niigata International Animation Film Festival 2024]

Yoshiyuki Tomino is, without any doubt, one of the most famous and important directors in anime history. Not just one of the creators of Gundam, he is an incredibly prolific creator whose work impacted both robot anime and science-fiction in general. It was during...

“Film festivals are about meetings and discoveries” – Interview with Tarô Maki, Niigata International Animation Film Festival General Producer

As the representative director of planning company Genco, Tarô Maki has been a major figure in the Japanese animation industry for decades. This is due in no part to his role as a producer on some of anime’s greatest successes, notably in the theaters, with films...

Hello! Thank you so much for such an awesome interview. Can you clarify, please, Iso and Honda are literally been fighting (beat each other)? Or was it about a quarrel or something?

Hello, thank you for your comment 🙂

The fight was an argument, not throwing punches at each other. Still, they had big resentment for each other for a while.