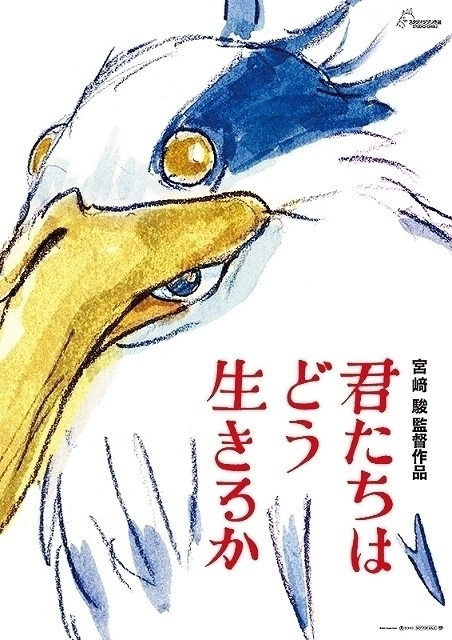

Saying that Hayao Miyazaki’s latest (last, definitely?) film, How Do You Live? was highly anticipated would be an understatement. The complete lack of promotion and secrecy around it until the day of release, expected to last some more as I’m writing this, has only increased the mystery surrounding it. This review will not completely lift it – it will be as spoiler-free as possible, although I will obviously not be able to avoid some reveals about its contents.

First, it appears necessary to underline how exceptional this film is. The lack of promotion around it is just the external sign of a completely independent production – no production committee, no company besides Ghibli itself involved in its financing. As has been noted many times already, this is a bold move coming from the company which popularized, not to say almost initiated, this now controversial financing and distribution model. Begun, it is said, around 2016, its credits might give the impression of a small production, key animated by only around 20 people over the course of multiple years. Among them, we find Ghibli regulars like Akihiko Yamashita or Katsuya Kondô, people who have not been seen on the master’s production for some years like Masashi Andô (and rumors of an uncredited Osamu Tanabe, although he had retired from animation), some of Japan’s greatest animators such as Toshiyuki Inoue or Shin’ya Ohira, but also younger artists one would not expect to find alongside Hayao Miyazaki, chief among which Yoshimichi Kameda.

As was already well-known, all of them worked under the supervision of Rebuild of Evangelion designer and animation director Takeshi Honda, whose presence on How Do You Live? plays no little part in the quality and novelty of the film. Miyazaki’s rich and round designs and movement remain as beautiful as they have always been, but are balanced by thinner, more elegant lines and features and more liberated expression than the highly-controlling Miyazaki has been used to – particularly visible in Ohira’s uncorrected, harrowing opening sequence or the film’s impressive climax. This may be the most original take on Miyazaki’s style since Katsuya Kondô’s wonderfully delicate designs on Kiki’s Delivery Service.

Unsurprisingly, How Do You Live? is technically stunning. Almost entirely focused on character animation – there are remarkably few effects performances for a Miyazaki film – it is also served by a powerful, diverse art direction, open about its influences ranging from Miyazaki’s previous works to Western painting, but also, as always, by Joe Hisaishi’s music, which seems to become increasingly minimal as time goes by. Although Ghibli’s difficulties have been no secret – the studio closed down and reopened repeatedly according to Miyazaki’s entries and exits of retirement – the master has managed to gather around him some of the best artists in the Japanese animation industry, to produce splendid results.

Praising How Do You Live?’s artistic qualities is the easy part. Narratively, the film is difficult to assess – I’m not sure how to feel about it after the first watch, and I think it should prove divisive among audiences, like its predecessor The Wind Rises. By that, I am not saying that it is similar – it is completely different, although the autobiographical elements are both more pronounced and less obnoxious this time. It is, in fact, quite unlike most of Miyazaki’s previous films, especially its early part.

Indeed, How Do You Live? can be neatly divided into two very different parts. The first one could be described as a slowburn fantasy horror film, reminiscent of Pan’s Labyrinth. Exceptional in Miyazaki’s body of work, it makes for a slow, disturbing, masterfully handled opening act – think of it like Spirited Away’s beginning, but far longer and even more unsettling. Following from there, it slowly transitions into what I’d call “fairy-tale” territory, that is more classical Miyazaki-esque, self-pandering fantasy. The characters and viewers progressively enter an incredibly rich, imaginative and complex world, one of those things for which the Japanese director has become so famous. While I am not sold on all of its aspects – after such a unique first act, the attempts at comic relief and some of the most self-referential moments fell flat – it is perhaps one of the most ambitious fictional universes built by Miyazaki: the landscapes are varied, never repetitive, and never fail to conjure a sense of wonder. One of the film’s most striking aspects, and perhaps what might make it a difficult watch for some, is how slow it is. This does not just apply to the atmospheric beginning, but also to the second part: while a classical Miyazaki adventure, it takes pains to keep the universe and its laws as impenetrable as possible. There is none of the exhilarating energy one might find in Laputa or even the density of Spirited Away‘s world: the sense of wonder is still there, but it is far more contemplative.

That dimension can probably be understood in the continuity of The Wind Rises and How Do You Live? certainly follows it in its introspective aspect, perhaps the product of an aged artist coming back on his life and creations. But, thankfully, it does not fall into one of the trappings that could be expected from this and the title: I feared a moralizing, perhaps even bitter film coming from an old man whose controversial positions have never been a secret. Nothing could be further from the truth: unexpectedly borrowing from sekai-kei and portal fantasy tropes, this film about trauma and grief closes on an optimistic, hopeful message. It certainly has something to say to younger generations, but is never patronizing – in that, it is one more proof of Miyazaki’s talent as a writer.

Thanks to its ambition, variety and depth, it is difficult to think of How Do You Live? as Miyazaki’s last film, the testament that we have all been led to expect. Treading both old and new ground, it illustrates how the director’s creativity is a deep well that never seems to dry up. It might be absurd, but at this point I just want to wish for another film in that vein, that would build upon its strengths, continue to tread the new roads it opened, and correct some of its faults. It is a difficult work, and as written, I do not think that it will work for everyone – I’m not even sure it worked for me. But this difficulty and ambiguity might be its best quality, Miyazaki’s ultimate showcase of talent, nuance and imagination.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

Thank you for the impressions! I hope for a fast release oversees.

Thank you ! I’m not sure I’ll read a better piece any time soon about this film without spoilers.