Ekura Animal, or Eclat Animal, is an animation studio with a long history: created in the early 1980s, its roots go back to the very beginnings of Japanese animation and the students of one of anime’s greatest artists, Yasuo Otsuka.

At Full Frontal, we have known about Ekura Animal for some time, as some of our members had been supporters of their crowdfunded project Kaze no You Ni, a film adaptation of Tetsuya Chiba’s work reuniting some of the most famous veterans in the anime industry, among which legendary animator Manabu Ohashi.

Today, Ekura Animal is organizing a new crowdfunding campaign, with the help of JETRO’s initiative to support independent anime studios and their creations. You can read more about the other campaigns supported by the initiative here. Ekura Animal’s project is an adaptation of a classic of Japanese literature, the Heike Monogatari in an original format: papercut animation. We had the opportunity to discuss the challenges of such an adaptation with the studio’s representative, Ms. Hitomi Toyonaga.

If you want to learn more about the studio, you can also check out their Youtube channel.

Could you begin by introducing your studio, Ekura Animal?

Hitomi Toyonaga: I am currently the third representative of the company, which was created in 1982 under the name Animaru-Ya by 7 animators from studio Shin-Ei Douga. Then, the name “Eclat” comes from another studio called Eclat, which merged with Animaru-Ya when I joined, so we merged the two names. Eclat means “shining” in French, I guess you could say our name is “Shining Animals”?

As for our vision, it rests on three pillars. First, there’s TV work, which we call “food work”, or what we do to keep eating and maintaining a sustainable business. Then, there’s our original projects, which we make on our own and call “life work”: what keeps our hearts and spirits going. Finally, we make various contributions to society and local initiatives. This is what Eclat Animal is about.

You mentioned the production of original works, what original projects have you done so far?

Hitomi Toyonaga: As a company, we’re specialized in works for small children, so a lot of our independent productions are aimed at children as well. The first one we made was called Okaa-san no Yasashii Te (Mom’s Gentle Hands)… but it wasn’t completely made by us, as many other people and other companies contributed to it. Then, among our next projects, the most important one was the Daruma-chan series, adapted from Satoshi Kako’s picture books. There are around 6 books, which are quite popular among very young children in kindergarten. However, due to various difficult IP-related circumstances, we can’t commercialize our work and we can only provide it for free on the net… Now, in general, whenever we encounter a work that we love or that moves us, we try to find ways to adapt it.

Among your independent productions, there’s the film Kaze no You Ni, which you made a few years ago. Can you tell us about its origins?

Hitomi Toyonaga: Actually, there’s quite a romantic, beautiful story behind Kaze no You Ni. It started in 2003. In Japan, there are two great female manga artists: Machiko Hasegawa, the creator of Sazae-san, and Toshiko Ueda. Since Sazae-san was adapted in animation, Ms. Hasegawa’s work has become very, very famous. On the other hand, Ms. Ueda, even though she has a lot of talent, has also done various things outside of manga. One of our members, animation director Toshiyuki Honda, has loved Ms. Ueda’s work since his childhood, and when Ms. Ueda’s Fuinchin-san was republished, his passion was rekindled and he wanted to adapt it to animation. This adaptation was announced at a small wedding venue in Shibuya called Blue Hall. Originally, during the war, Ms. Ueda lived in occupied Manchuria, and there she acted like an older to many other manga artists, including Tetsuya Chiba, who came to the screening. Mr. Honda and I are huge fans of Mr. Chiba’s work, especially of Kaze no You Ni. So even though it was a party for Ms. Ueda, we went to ask him if we could adapt Kaze no You Ni in animation, and he accepted. That’s how it happened.

On Kaze no You Ni, there were a lot of veteran animators such as Keiichirô Kimura or Manabu Ohashi. Were you or Mr. Honda closely acquainted with them?

Hitomi Toyonaga: Well, the world of animation is quite small, you know! So even if you haven’t directly worked with someone before, you may have seen them somewhere, or know where they work and how to contact them.

But in this case, it wasn’t just about connections between animators. Mr. Honda is from Gunma prefecture, which is where Kaze no You Ni takes place. And it so happens that many members of the team also had connections with Gunma: Keiichirô Kimura came from there and the actress Masako Nozawa, who played the protagonist, had been evacuated there during the war. So “Gunma” was the keyword which connected the entire team.

We were also very happy, because Ms. Nozawa won a prize at the Nihon Eiga Hihyouka Taishou for Kaze no You Ni, which isn’t even a real feature. Ms. Nozawa played lots of roles during her career, but it was the first time she received such a prize and it made us all extremely happy. That’s why Kaze no You Ni is extremely precious for all of us.

I believe Kaze no You Ni was financed by a crowdfunding campaign as well. Can you tell us about it and what you learnt from it?

Hitomi Toyonaga: We began this campaign at around the same time as the one for another animated film, set in Hiroshima, In This Corner of the World. Someone from a film distribution company came to see us one day, and told us how popular In This Corner of the World’s campaign was, so that’s how we became aware of crowdfunding. The goals were naturally very different, and In This Corner of the World eventually gathered millions of yen, which made us a bit jealous but also motivated us…

The biggest difficulty we faced with crowdfunding is how to advertise and present our work. We’re involved in production, so we don’t really know about things like that: we know how to make animation, not how to sell it. We believe that if what we’re doing is really good, it might reach people, but things aren’t always that simple.

In the end, crowdfunding is the collection of people’s good will, unlike production committees which are all about generating revenue for all the people involved. But the consequence is that, with crowdfunding, we have to think about how to pay back the supporters: as I said, we’re people from production, so we need help from people able to support this process, and we had to hire part-timers to help us with this. At the end of the day, what made Kaze no You Ni work was Mr. Chiba’s fame and the power of his creation.

Regarding the difficulty of promoting your works, I suppose JETRO’s help this time was quite useful.

Hitomi Toyonaga: Indeed. In JETRO, there are people who have a background in marketing, who play the role of producers, and they provided helpful support for us, because that’s precisely what we’re missing. We’d like our productions to spread to the entire world, and so we’re very happy for their help.

This crowdfunding campaign is international, but you’re adapting a very Japanese work, the Heike Monogatari. How do you think it can appeal to overseas audiences?

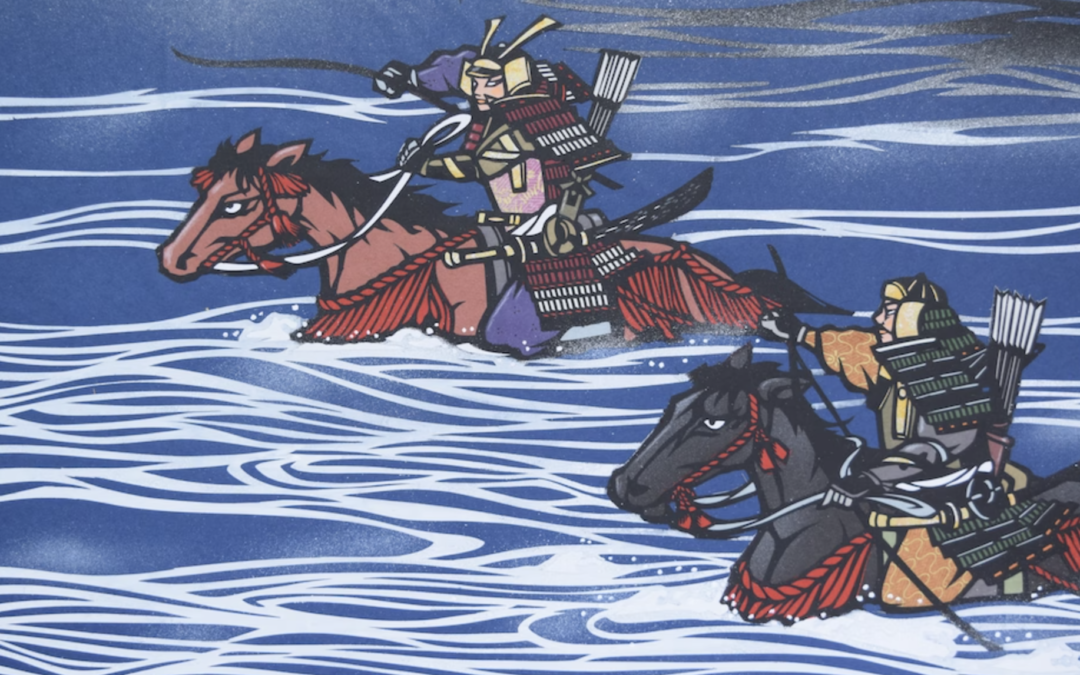

Hitomi Toyonaga: First, I’d like to tell how we decided to make this. At first, we encountered the work of papercut artist Shû Koide when he published an artbook. I thought I wanted to spread his work by making it in animation and directly asked him. In 2011 or 2012, he won a prize at a contest in France, so work like his is already appreciated: perhaps not in all of Europe, but at least in France, Japanese culture is strongly valued. So I thought that we had to make it more well-known. First, we received Mr. Koide’s original works and started production from there.

As I said earlier, Ekura Animal is focused on productions for children, and one of the questions we often ask ourselves is, what do we leave for the future generations? The Heike Monogatari may be for adults, but there’s no real distinction for us: as creators, we create what we want to create and deliver the messages we want to deliver. We just happen to specialize in animation for children. We’re putting all our passion in the Heike Monogatari. It’s a difficult text, but it’s possible to spread it to the entire world through pictures and animation, and I’d be happy if more people could receive it.

So the original work is papercut illustrations. Will the animation be traditional 2D animation? How will you adapt the papercut style?

Hitomi Toyonaga: First, Mr. Koide sent us the drawings he cut, and we didn’t want to lose the special atmosphere and sense of presence of papercut drawings. That would have happened with normal 2D animation, and it would have killed the artwork. So we had Mr. Koide draw some of the movements, for example someone shooting a bow, and then we scanned them and added some effects during the compositing, for example for flames. The compositing is more-or-less done right now, but we still want to go further with image processing. We really don’t want to do ordinary 2D animation.

What will be the format?

Hitomi Toyonaga: A bit shorter than 50 minutes, but with the opening and ending it should be a bit longer than that.

How is it to work from papercut animation?

Hitomi Toyonaga: We’re a 2D animation studio, but we also did some stop-motion or illustration work for kamishibai. We’ve also worked on series like Nihon Mukashibanashi, which is done through the traditional process. But before this Heike Monogatari project, Mr. Koide was already interested in animation and moving pictures, so we asked him to do papercut artwork for Nihon Mukashibanashi: he cut every frame, instead of drawing it, and in the end he said he had enjoyed it a lot. But cutting every single frame is very long and difficult. In the end, papercut and drawings are very different, and it might have been the only time that Mr. Koide did everything by himself like this.

Last year, there was another animated adaptation of the Heike Monogatari, by studio Science Saru. Did you have the opportunity to see it?

Hitomi Toyonaga: I’ve watched some of it. The animation was very good, and the music very original: not Japanese-style, but a bit different. I really like music, so I appreciated the way the music was integrated… The Heike Monogatari is a difficult work, and I was very glad to see how well it made it available to a broader, younger audience. Adaptations of classics happen from time to time, and as a creator, even though every interpretation of the work might be different, I’m always happy to see them being shared with more people.

I see. To conclude, would you have a final message for the people supporting the campaign?

Hitomi Toyonaga: I’d like to come back on why we’re making the Heike Monogatari now. It’s a war story, about the conflict between the Heishi and Genji clans, with the central theme of impermanence. But what I feel from the Heike Monogatari is a reflection on how to approach death, and how we should live with that perspective. It’s a sort of memento mori: we’re all going to die one day. It’s possible to take this negatively, as if everything was always bound to end, but personally I take it differently: if we’re all going to die, how should our life end? How do we live in the time that’s left? As human beings, I think it’s something very important, that we should all be thinking about. So in the end, I think that the main question is, how should we live now? I’d like to think about this together with our viewers, and I believe that’s a message that transcends borders. Conflicts and wars are going on all over the world, and of course we can’t just stop them like this, and what animation can do is very limited, but I’d like to offer even a small opportunity for more people to consider these things.

All our thanks go to Ms. Toyonaga for her time and the JETRO Marketing division for their help in organizing this interview.

Interview & transcription by Matteo Watzky.

You might also be interested in

From picture books to animation: Noko Yukawa & Studio Gorilla [JETRO x Kickstarter]

Studio Gorilla is a small studio with a long history. As is often the case in the anime industry, its creators are fueled by simple things: love and passion. With these, they have participated in a variety of projects aimed at children, which have always been their...

Looking for a Japanese new CG: Yuta Sano & Studio 4°C [JETRO x Kickstarter]

Studio 4°C is one of the most famous animation companies in Japan. For decades, they have created many experimental films and have acquired a passionate fandom overseas. Right now, the studio is embarking on a new project which will require the help of such fans -...

Breaking the Mold: making Hana the Last Diviner – Interview with Hiroki Taniguchi [JETRO x Kickstarter]

Hiroki Taniguchi is an independent anime and film producer and director who is the head of the studio Public Arts, a tiny company as it has only one permanent member: himself. Mr. Taniguchi has been selected to participate in the ongoing initiative by JETRO aiming...

Trackbacks/Pingbacks