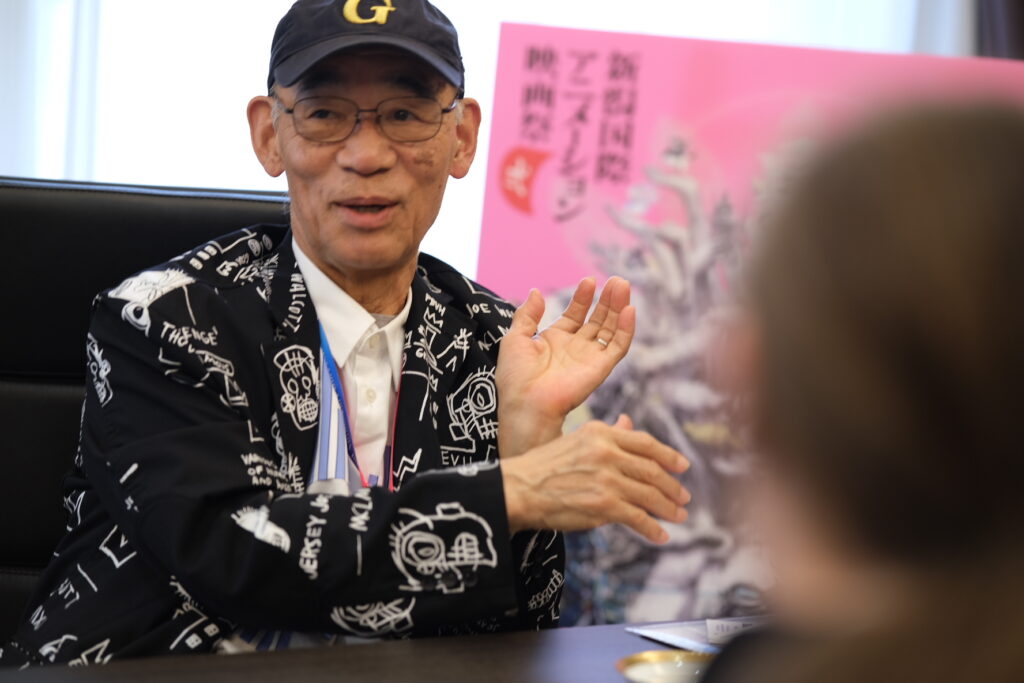

Toshiyuki Honda’s name may not be familiar to many anime fans, but he is the very definition of a veteran, one of those people who have supported the anime industry for decades. He started his career in 1969 in the genre-defining sports anime Star of the Giants and has since then worked on many staples of anime, most notably Doraemon.

Aside from his work as an animator, Honda has worked alongside some of the greatest names in the industry and has been involved in a variety of activities. As a member of Daikichirô Kusube and Yasuo Otsuka’s legendary studio, A Production, he worked next to future Studio Ghibli members Hayao Miyazaki and Yoshifumi Kondô. He was also involved in union activities, which were extremely active in the anime industry of the 1970s.

Today, Mr. Honda is the main creative at the animation studio Ekura Animal. At fullfrontal.moe, we’ve had many opportunities to talk with people from the studio, from president Hitomi Toyonaga to director Hiroki Taniguchi.

This article would not have been possible without the help of our patrons! If you like what you read, please support us on Ko-Fi!

This interview is available in Japanese. 日本語版はこちらです。

The studio where you’re working is Ekura Animal. I believe that it used to be called Animaru-ya, right?

Toshiyuki Honda: I like French, which is why it was changed to Ekura Animal, because “éclat” means “shining” in French, right?

Apparently, you have to be able to lift a heavy barbell in order to enter the studio. Is that true?

Toshiyuki Honda: To become an animator, you have to have a light pencil touch. I thought about that back when we created the studio, and I decided that they’d also have to be able to lift a 40kg barbell. Because you can’t just rely on your pencil! (laughs) You need to have some physical endurance as well.

Aah, I see. (laughs) I’d like to ask about your career. It started in 1969 at studio A Production[1]. How did you enter it?

Toshiyuki Honda: After high school, I initially wanted to become a civil servant. But I failed the entrance exam, and I kinda drifted for some time. It was then that my high school teacher introduced me to the father of Daikichirô Kusube, the president of A Pro, and he gave me a recommendation. That’s how I joined, through personal connections. It was pretty frustrating: I got in not through my artistic abilities but because of connections.

How did you learn to draw? Did you have a master?

Toshiyuki Honda: At A Pro, I was taught by Yasuo Otsuka[2], and Hayao Miyazaki, and there were many other experienced people who taught me, but they tended to reject everything I drew. (laughs)

So they were pretty strict?

Toshiyuki Honda: They were, but it was a really fun studio. There was no distinction between men and women, which was unusual at the time. Everybody was fun and liked to make pranks, so it was a really good time. And my seniors were all good as well, so I also learned a lot.

I believe you joined a labor union there, right?

Toshiyuki Honda. Yes, I believe they wanted to call it the “Motion Pictures & Broadcasting Industries Labor Union”, but it ended up with another name… Personally, I wasn’t really interested in politics, but my colleagues invited me, so I joined anyway. You know, there was this writer called Takiji Kobayashi, who was a member of the Communist Party and got tortured and murdered by the police back in the 30s. Once, there was a reading of his stuff, and I said I didn’t want that to happen to me! But they told me that wasn’t the kind of thing that happened in unions, so I ended up joining.

I guess my role was to bring in new members. I’d invite freelance animators, people like Yoshinori Kanada[3] and such were there. Everybody was really nice, and we’d mostly just eat and drink! We were pretty relaxed back then.

You also made your own film, Tsugu no Sugomori, right?

Toshiyuki Honda: That was adapted from a story by Terutoyo Takakura. With other people from the union, we rented a small apartment in Ichigaya, in Tokyo – there was a JSDF base in the area back then, and we were next to it. It was around the time Yukio Mishima committed suicide, so that must have been in 1975. You might still be able to find that film today… But basically, we gathered there to work on it after we were done with our day jobs and did it at our own pace.

Nowadays, there are lots of debates regarding the working conditions of animators. As a former union member, do you think that the return of labor unions could be a solution?

Toshiyuki Honda: You know, we were really small. The production companies were really small and weak, so when we approached their owners to ask for raises in wages and guarantees, they didn’t have the money to do that, and it went nowhere. That’s why we tried to emphasize our position as a union and cooperate with the major agencies and TV stations.

However, the future was uncertain, and for some reason, performance-based management was gaining ground in Japan. Especially since the 1980s, we saw an increase in freelancers and non-regular employees in the animation industry, which weakened the union’s organizing power. Maybe this encouraged animators to unite and become more organized, but… And weirdly, it was at the same time that animation started to become really popular.

I’ve heard that Yoshifumi Kondô[4] joined the Communist Party because of you…

Toshiyuki Honda: I don’t know about that! (laughs) Back then, most left-wing movements were supervised by either the Communist or the Socialist Party. One day, they both joined together to support Ryōkichi Minobe as the Governor of Tokyo. I guess that led a lot of people to get into politics.

As for Kon-chan, we worked together at A Pro, and after that, he joined Ghibli, where he directed Whisper of the Heart, right? He was really good at drawing, a true genius.

Do you think Mr. Kondô ever considered joining Animaru-ya?

Toshiyuki Honda: After A Pro became Shin-Ei, Kon-chan joined Mr. Miyazaki and others at Nippon Animation. In our case, we created Animaru-ya after everybody was gone from Shin-Ei: first people left to create Ajia-Dô, then Nippon Animators Group, then Studio Colorido, and we were the only ones left… There was nobody in-house, but we still got work, and that’s how we started working on Doraemon and Kaibutsu-kun. It was only a gag series, and of course, at some point, we started wanting to do something else. So we got together in a bar and asked Kusube if it was alright to create our own thing as well. Kusube was someone really kind, and he really understood us – he had done the same thing, going independent from Tôei when he was young after all – so he told us, “Ah, men always want to fight their own battles at least once in their life” and “go for it, I’ll give you work”. He really supported us, as far as helping us find a place.

By the way, Kusube was originally my high-school senior from back in my hometown. Same for Keiichirô Kimura[5].

Oh! Was Mr. Kimura really a yakuza, then?

Toshiyuki Honda: No, not at all! He was really kind, but with how he looked… (laughs)

He looked like Ikki Kajiwara, didn’t he?

Toshiyuki Honda: That’s a good comparison! (laughs) He really had a unique body… He looked just like a pro wrestler, and he used to wear gold necklaces or open up his shirt… So, of course, he’d stand out! But he was really kind.

Do you have any particular stories of being with Mr. Kimura?

Toshiyuki Honda: Well, you know, his wife owned a bar. So every time we wanted to get a drink, we’d go there. But when we entered, his wife would shout, “Dear, don’t come in from the front! What will people think, take the back entrance!” (laughs)

(laughs) Going back to your career, I’d like to ask about Panda! Go, Panda! What was it like working with Mr. Takahata and Mr. Miyazaki?

Toshiyuki Honda: Panda! Go, Panda! was a pretty special project. At first, Miyazaki planned to make an adaptation of Pippi Longstocking, but in the middle of that, Toho suddenly asked us to produce something involving pandas when Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka and Premier Zhou Enlai shook hands, restoring diplomatic relations between Japan and China.

How was the production? Was it fun?

Toshiyuki Honda: I had a lot of trouble on it. I was responsible for the scene where Miichan, the main character, makes some fried eggs. My seniors advised me that learning through experience was crucial and that I had to be patient. But when I brought my drawings to Miyazaki, he just took a glance and threw them away. (laughs) I redid it I don’t know how many times, and I kinda gave up in the end. I cooked so many eggs for that scene! And I could never tell what was wrong with my animation. But now, I guess that Miyazaki wasn’t happy with the animation of the oil splashes; maybe they should have been more random.

That’s how we learned back then. Miyazaki’s own teacher, Yasuo Otsuka, was similar. He played baseball, you see. And when I worked on Star of the Giants, the same thing happened. There’s a scene where the main character’s face looks like it’s burning, and his rival’s face appears under it on the screen. I was told that the flames I drew weren’t good so many times, I redrew them over and over. At some point, I was fed up with it, so I asked them to let me get away with it, and Otsuka showed me how it should go with the flame of his lighter.

Everybody was like that. Also, you couldn’t really rewatch things back then: TV shows aired once, and you wouldn’t really be able to rewatch them unless there was a rebroadcast. So everybody kinda drew as they liked. For instance, Miyazaki and Otsuka put their own portraits in Lupin III a lot. For instance, there’s this car chase scene, and Lupin drives through the middle of the house, and the family eating there is Miyazaki’s.

This kind of thing happened all the time. It also did on Tensai Bakabon. Everybody was just having fun. I learned how to make gags at the same time as animation – it was the moment I passed the exam to go from in-betweens to key animation. There were three exercises: first, you had to draw a boy jumping from a box, then the second was a girl lifting a rock, and the third was a gun action sequence from Lupin III. Most people failed one or two times, and only Yûzô Aoki, whom everyone considered a genius, passed it the first time.

As for me, for the second exercise, I couldn’t imagine how a little girl could lift such a heavy stone. So what I did was draw her drinking some magical potion, which made her super strong. Otsuka saw that and liked it, and that’s how he suddenly admitted me to the key animation team. I guess he liked that I never stopped making jokes! (laughs)

(laughs) After that, you worked on Gamba’s Adventure. Unlike the previous shows you worked on, most of the staff didn’t originate from Tôei but from Mushi Pro.

Toshiyuki Honda: That’s right, it was a sort of collaboration between the Mushi and the Tôei people. Osamu Dezaki[6], from Mushi, was the director, and the animation director was Yoshio Kabashima, originally from Tôei. Tôei and Mushi had pretty different approaches, but it’s on this series that they were first brought together.

Did you feel that difference between the two?

Toshiyuki Honda: Yes, they were pretty different. Mushi Pro was created by Osamu Tezuka, who was a mangaka. So, for example, in Jungle Emperor, the main character runs with the neck straight, as he would if it were manga. But the Tôei people thought this wasn’t really animation. For them, movement was about realism. It wasn’t supposed to resemble manga. In particular, it seems that Miyazaki and Dezaki didn’t really get along. Miyazaki kept making fun of Tezuka’s style, and that didn’t really sit well with Dezaki. (laughs)

I helped out at a signing session held by Tezuka once, and it was there that I realized what a genius he was. His drawing ability was really exceptional.

Anyways, a lot of stuff like that happened, and at the end of the meetings with the animators for Gamba, Dezaki would ask us what scenes we wanted to do. We’d say we wanted to do such a scene, but we were always given something else than what we had asked for! In my case, Dezaki asked me to do the very first scene of the show.

Not long after Gamba, A Pro and TMS stopped working together. Do you know why that is?

Toshiyuki Honda: I believe that just after Gamba, we still worked for TMS on Hajime Ningen Gyatorz. It was an adaptation of a manga by Shunji Sonoyama, and I think that was our final project together.

The director of Shin-Ei Dôga and the president of TMS were brothers-in-law. Also, Sankichirô Kusube, the younger brother of Shin-Ei’s president Daikichirô Kusube, was a producer at TMS. I think these familial relationships are one of the reasons why both companies went their separate ways. Then, Shin-Ei started working on Doraemon, which was a huge hit, and it became truly independent.

But A Pro/Shin-Ei animators still worked on TMS’ Ganso Tensai Bakabon after the split happened, right?

Toshiyuki Honda: That’s right. Things are a bit special in this industry, you know. You could say it was an underground deal: basically if someone you knew asked you to assist them, you’d do it like a part-time job. Everybody knew each other, so we’d always help out. We did that kind of stuff but asked to remain uncredited when it happened.

Ah, yes, so for instance, on Shin-Ei’s Tenguri, Boy of the Plains, Hayao Miyazaki or Yôichi Kotabe did animation, but they weren’t credited. Was that the same thing?

Toshiyuki Honda: Back when I joined A Pro, Miyazaki and the others weren’t members of the company yet. They only joined after a few years. Anime production started to change quite a bit after that: the production standards and the quality of the shows increased. They worked really well together. For instance, Heidi, Girl of the Alps happened because Takahata, Miyazaki, and Kotabe worked together. They formed a very good and efficient team.

Tenguri and Heidi feel similar, don’t they?

Toshiyuki Honda: Yes, they do. If I remember correctly, Tenguri was a promotional film for a milk company called Snow Brand, and it was Otsuka’s first work as director. Miyazaki did a lot of key animation on it. Back then, A Pro had a thing with Mongolia: Mr. Kusube was a big Genghis Khan fan, and he planned to make a show called The Blue Wolf about him. I worked on that pilot; there were tons of horses, and Kusube asked me to work on it. A single shot took me a week! (laughs)

Why did Otsuka direct Tenguri in the first place?

Toshiyuki Honda: Hm, maybe because there was no one else available? I don’t really know, but Otsuka could do pretty much anything: he’d help the production assistants on TV series, for instance. And perhaps he wanted to try out direction as well. Of course, he was an animator first and foremost, and I don’t know what the higher-ups had in mind, but Otsuka ended up directing.

It was around that time that you became close with Hiroshi Fukutomi [7] on Manga Sekai Mukashibanashi. How did the two of you meet?

Toshiyuki Honda: I’m one year older than him, you see. We got close because we both like drinking, especially shôchû. There were a lot of bars next to the Koenji station back then, and we went there to drink all night – we were so drunk we’d often throw up in the street! (laughs) Back then, people in the neighborhood used to call me “Macchan”, which is a reference to a character from Tetsuya Chiba’s Notari Matsutarô. Apparently, I looked like him. I guess that’s because I was kinda big and tough back then.

(laughs) That’s pretty fun! You also worked on Ore Wa Teppei back then, and this time, Shin-Ei was a subcontractor for Nippon Animation. How was it?

Toshiyuki Honda: I was still working at Shin-Ei back then, but since we had broken away from TMS, we went back to square one with subcontracting, and that’s how Nippon Animation approached us for Ore Wa Teppei. The director was Tadao Nagahama, who had become famous with Star of the Giants, and Otsuka was there to provide support. Nagahama and Otsuka were really good friends. They used to play poker, go out, and joke all the time. What they said about the show was that there should be one gag in every shot. It went wild. (laughs) Isn’t that crazy?

Wasn’t Teppei your debut as animation director?

Toshiyuki Honda: No, I started animation direction just after that, on the baseball anime Ikkyu-san, adapted from Shinji Mizushima’s manga. Mizushima just loved baseball, so when we first met for the show, we just talked about that! He smoked a lot… Back then, manga artists didn’t really care about anime, so he told us we could do as we pleased. Things aren’t the same now, though.

You then moved on to Doraemon. At first, there was one new episode aired each day. Didn’t that make it really difficult?

Toshiyuki Honda: Well, after the first Doraemon movie, I moved to Kaibutsu-kun, and I didn’t really work a lot on the TV series. I guess I must have done a few storyboards under a pen name, tough.

You’re credited under “layouts” on a lot of Doraemon movies as well.

Toshiyuki Honda: Yes, I did a lot of that. Basically, I drew all the layouts for the film myself. It was a pretty important job.

All the layouts by yourself?

Toshiyuki Honda: That’s right.

You were also very close to Shin’ichi Suzuki and Yoshiji Kigami[8]. How did that happen? Was that also because you went out drinking?

Toshiyuki Honda: It was during the production of the Kaibutsu-Kun TV series. I was also working on the movie and the TV special, and I was too busy to do it all myself. So I asked for their help. The three of us managed to complete all of it together. Kigami was extremely talented: he was extremely quick and so good that he got promoted to animation director very quickly. People said that there was nothing he couldn’t draw or that he was just as talented as Miyazaki.

You created Animaru-ya together, is that right?

Toshiyuki Honda: Yes, we all liked drinking, as you said. The first president, Yoshinobu Sanada, loved drinking as well, and he ended the ideal way for a drinker: he died from cirrhosis of the liver. Everybody had a lot of respect for him, and that’s how people naturally gathered around him. It felt like we were the Seven Samurai from Kurosawa’s film. We didn’t have to do anything for work to arrive, and it felt like we were partying all the time. These were really fun days.

I believe you did some uncredited work at the time? Outside of Animaru-ya.

Toshiyuki Honda: Well, rather than a proper company, Animaru-ya was like a gathering of freelancers. So, for instance, Kigami would go help out at Ghibli, he also worked on Akira, and he got all kinds of offers from great animators. We were all in the same situation, receiving a lot of offers. Among those, I remember working on a gag manga adaptation called Ojamanga. Suzuki was also approached by Nippon Animation for Locke the Superman. That’s how things happened.

The first thing we produced together as a company was the baseball OVA Midori Yama Kouko no Koushien. Each episode lasted around 40 minutes. We also worked on multiple American co-productions, things for Disney or Warner Bros. We also did the pilot and opening for Powerpuff Girls… I never thought it would become so popular! There was also some project for Steven Spielberg. We really worked on all kinds of things.

But the American system is so streamlined that they do things in a way that would be impossible to imagine in Japan. For example, if a mistake is found during production, the Japanese would try to do something about it, but the American director would say that correcting it isn’t their job. There were a lot of differences like that. I also worked in Taiwan, and the studio was huge, huge enough to have its own baseball team with American and Japanese players. I kinda let them do their own thing, but they came to call me “the baseball monster” because I only hit home runs! I guess it’s a fun memory! (laughs)

You also served as animation director for a film in Hong Kong, Old Master Q and Little Ocean Tiger. How did you get involved in Chinese films?

Toshiyuki Honda: I was introduced there by a friend from Taiwan. It was to adapt a comic that was quite popular in Taiwan, but things were a bit strange. The publisher held the copyright for the series, and the son of the original author continued it under his father’s name. I was introduced to the publisher around 2010, and the film was produced by a Chinese company, Huayi Brothers.

I went to Shanghai, known for its many buildings along the famous Huangpu River. There, a young Chinese couple approached me and asked me to take their picture. I didn’t expect to be asked for pictures, but I later learned that there’s a tradition where having one’s picture taken by 1,000 different people is supposed to bring happiness to a couple’s life. At that time, I felt like: “Leave me alone! I’m an animator, not a photographer!”. (laughs)

I believe that Animaru-ya was also involved in the film Gamba to Kawauso no Bouken. How did it feel working on Gamba again?

Toshiyuki Honda: Well, we were approached by TMS, and I worked on the animation, but the main member was Suzuki. We got to know the director from TMS, Shunji Oga, over drinks, and I guess it all went from there! You could say most deals in the anime industry are made over drinks! (laughs)

Wasn’t it lonely without Dezaki directing?

Toshiyuki Honda: It’s true that Dezaki wasn’t there, but I think that Oga directed it precisely because he was Dezaki’s disciple. Anyway, Oga and Suzuki really got along. They spent their time drinking.

You’ve worked on a lot of very different productions during your career, but which one would you say is your favorite?

Toshiyuki Honda: That’s a difficult question. To be honest, I’m not a huge fan of animation. (laughs) Actually, did you know that I worked on some French productions? It was produced by Jean Chalopin[9] at C&D. I think it was a comedy called “Manu” or something like that…

How did you get involved in Jean Chalopin’s works?

Toshiyuki Honda: C&D was created by people who had left TMS and Jean. And I got work from them, since I knew all the people who had worked at TMS. I also worked on Michel Vaillant.

Did you know Jean Chalopin is working for a bank now and was connected to the Panama Papers incident?

Toshiyuki Honda: I only met him once, and I thought he looked like John Lennon, didn’t he? (laughs)

Did you go to France for this occasion?

Toshiyuki Honda: No, I’ve never been to France. But I like French food! (laughs)

All our thanks go to Mr. Honda for his kindness and all the people at Ekura Animal for their welcome.

Ekura Animal has started offering studio tours in English, Korean, and Chinese, allowing to discover their production processes and learning more about how anime is made from veterans. For more information, you can contact Mr. Hiroki Taniguchi at gukoukun@gmail.com

Interview by Ludovic Joyet.

Assistance by Toadette, Matteo Watzky, Federico Antonio Russo, and Dimitri Seraki.

Transcription by Antoine Jobard.

Translation by Antoine Jobard and Matteo Watzky.

Introduction and notes by Matteo Watzky.

Notes

This article would not have been possible without the help of our patrons! If you like what you read, please support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Oshi no Ko & (Mis)Communication – Short Interview with Aka Akasaka and Mengo Yokoyari

The Oshi no Ko manga, which recently ended its publication, was created through the association of two successful authors, Aka Akasaka, mangaka of the hit love comedy Kaguya-sama: Love Is War, and Mengo Yokoyari, creator of Scum's Wish. During their visit at the...

Ideon is the Ego’s death – Yoshiyuki Tomino Interview [Niigata International Animation Film Festival 2024]

Yoshiyuki Tomino is, without any doubt, one of the most famous and important directors in anime history. Not just one of the creators of Gundam, he is an incredibly prolific creator whose work impacted both robot anime and science-fiction in general. It was during...

“Film festivals are about meetings and discoveries” – Interview with Tarô Maki, Niigata International Animation Film Festival General Producer

As the representative director of planning company Genco, Tarô Maki has been a major figure in the Japanese animation industry for decades. This is due in no part to his role as a producer on some of anime’s greatest successes, notably in the theaters, with films...

Recent Comments