The following is a translation of an interview with Yasuo Otsuka published in the 2003 Lupin III Perfect Book as a celebration of the show’s 30th anniversary. The interview goes over Yasuo Otsuka’s involvement in the license, the conditions of the show’s production and his relationship to other staff members, among others Hayao Miyazaki.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

Special Interview

Otsuka Yasuo – Looking Back on 30 Years of Lupin III and Forward to New Possibilities

Yasuo Otsuka

Born in 1931, in Shimane Prefecture, he entered Toei Douga in 1957.

After supervising visuals on works such as Hakujaden, he became the animation director for Taiyou no Ouji Horus no Daibouken, and subsequently transferred to Tokyo Movie. He has served as animation director on Moomin, Lupin III, Mirai Shonen Conan, Jarinko Chie, and others.

A Tumultuous Start

I must warn you from the start that, as it’s been over 30 years since the airing of the first Lupin series, and it’s been talked about in so many places and so many ways, it’s not like I have any new secrets to share with you. And also, the animation of Lupin I’ve been involved with is, at most, 1/60th of what exists. So many people have been involved in the anime version of Lupin, and I think it’s somewhat unfair that the spotlight hasn’t shone on some of them. For example, I’d personally be interested in hearing what Aoki Yuzo¹, among others, has to say.

Since we’ve settled those two items, I think it’s ok for me to start talking.

I first encountered the work now known as Lupin III as a result of my meeting one Fujioka Yutaka (President of Tokyo Movie/Deceased). Fujioka-shi had secured the adaptation rights for the Lupin III manga being serialized in Manga Action at the time, but the sponsors were as-yet undecided, and the project hadn’t gotten much traction.

Around that time, while I was still affiliated with Toei Douga, he came to me, saying, “I hear you like cars, Otsuka-san. I have this Lupin project here which you simply must be a part of.” I sensed some potential in the project, so I finished up at Toei and transferred to his studio.

Though we created a pilot film, the talks for a film adaptation were stuck in the mud.

A good 2 years had passed since we had entered production, with the project being dubbed ‘The Alleged Lupin.’

It was finally set to be aired on Yomiuri TV as a weekly anime. However, once the broadcast began, the ratings hovered between 6-9%, absolutely abysmal numbers for an anime program. The station instructed us to change the original concept, ‘A fresh anime program targeting older viewers,’ to that of ‘A kid-friendly program that could garner ratings.’ Osumi Masaaki, who had been very particular about the original concept, left as a result, and the reins were passed to the pair of Takahata Isao and Miyazaki Hayao, who at the time were affiliated with A Production.²

Takahata and Miyazaki Became Involved in Condition of Anonymity

The reason why those two became involved is fairly straightforward. As A Production was getting all its work from Tokyo Movie, that studio had no choice but to respond to our request for help. It just so happened that those two were on a separate, stalled project at the time, so they drew the short straw.

Also, since it was for me, an old colleague from their Toei Douga days, I guess they agreed to do it under the condition of anonymity.

The actual task of shifting the course of an anime already being broadcast was an exceptionally difficult one. The two would look over the storyboards, adjusting the story where possible, but it was a series where, time-wise, corrections were almost impossible to make. They took on the job requiring anonymity, so the two won’t talk about what was changed and where. And it’s been 30-odd years at this point, so digging up accurate records would be quite difficult. Really, though, you can basically guess what changes were made where, which is amusing.

In the end, it did end up as ‘The Alleged Lupin’ lasting not even 2 full cours before ending at episode 23. However, the more it was rebroadcast, the more praise it got, becoming increasingly more popular. Some factors there were, perhaps, the short, 23-episode length, a handy size that let local stations use it as filler, and that, thanks to the low ratings, the broadcast fees were cheap. Local stations are still airing reruns, even now.

The fans made their voices heard, spurring the station to act. When the new Lupin production was set, the one in charge at the station told me, “Otsuka-san, be happy! You can make part 2!” I remember being really happy when I heard this, but I couldn’t maintain my joy when I heard exactly what the new Lupin project would entail…

Have Computers Solved Mecha?

I’m often told, “You sure are strong when it comes to mecha,” but I feel it’s wrong to lump ‘mecha’ into a single term like that. Mechanical devices run on basic fundamentals; “There’s a clear cause, and the motion is the effect,” so it’s normally just a matter of following those logical principles. Animation means showing motion through art, depicting it with your art, so you simply have to start by studying those fundamentals and then building exaggerations on top of them.

Recent animation works are losing the budgets, the numbers, and the time to study the logic behind those movements before drawing them. There’s been no choice but to seize this stationary aesthetic and run with it, and, in exchange, the ‘art’ has become unstable in a way I can’t respect. Personally, I would want a work of animation to be something where, even knowing the story, one can watch it over and over for the satisfying motion, the appealing performances.

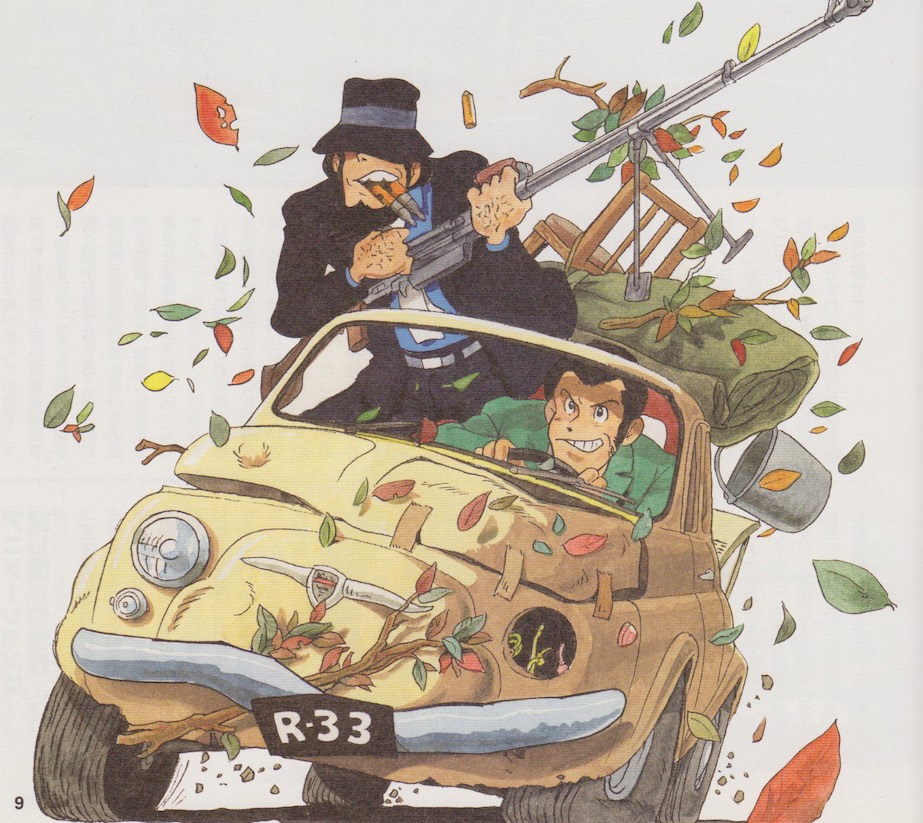

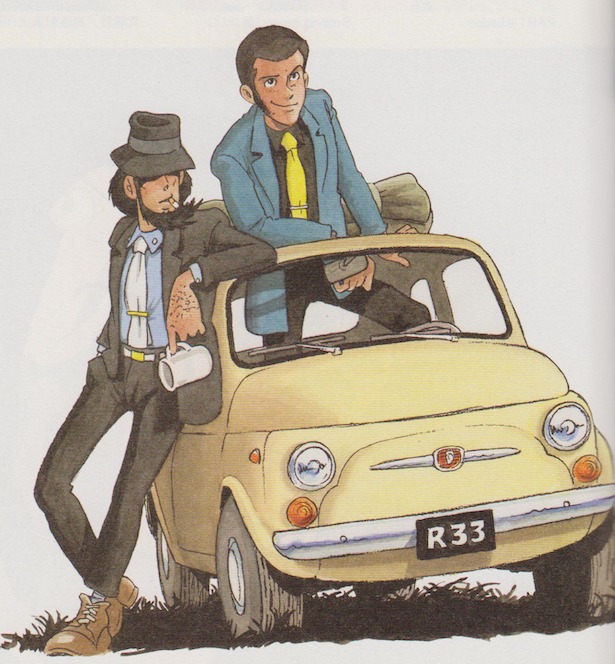

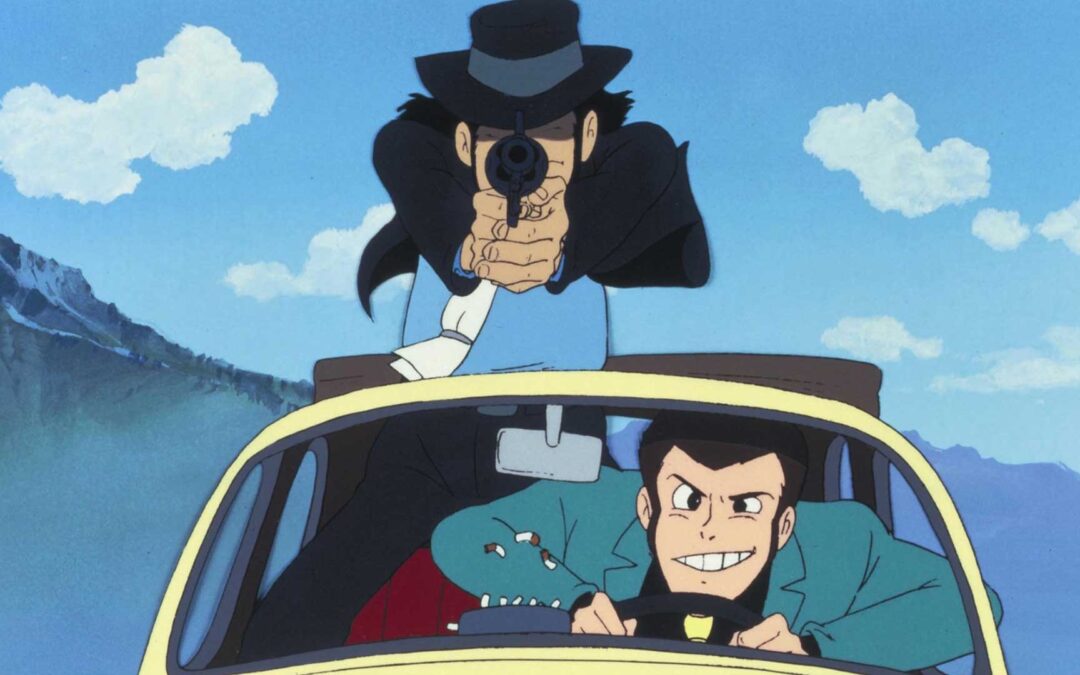

I often put a Fiat 500 (Cinquecento) into the show, but that was for no better reason than because I had driven it in the past and understood its mechanisms and depicted them enticingly on-screen. The recent digitization has advanced to the extent where you can show just the mecha component moving smoothly, realistically, without struggling much. But seeing realistic art suddenly pop in amidst traditional animation is not interesting at all, to say the least. It’s a field in need of further study.

The World of Animation is All About Give and Take

The reason Miyazaki-shi became the director for Castle of Cagliostro was that I accepted the job of animation director on his TV debut, Mirai Shonen Conan. As repayment me for that, when Tokyo Movie decided to make a theatrical film for the series, I told him, “I helped you out with Conan, and now it’s your turn,” which made it happen. It’s a world of Give and Takes, no matter what era.

The producer had prepared a script, but Miyazaki-shi thought things over himself within a short time period and created his own image of Lupin. The Lupin in Cagliostro is a slightly older, middle-aged one, and I think that’s the one that existed within Miyazaki-shi’s memories.

After that, he continued to lead the second TV series. At that time, around when part 2 was wrapping up, he directed two episodes, ‘#145: Wings of Death, Albatross‘ and ‘#155: Thieves Love the Peace‘, which have now garnered broad acclaim. However, when we delivered the finished film to the TV station, they outright refused to accept it.

The designs and plot both differed so significantly from what we had provided up to that point, so I may at least be able to see where they were coming from, but I can, at least, say with certitude that they were unable to recognize good work of substance. Apparently, it took Tokunaga Motoyoshi-shi³ (currently an executive producer for Walt Disney Animation Japan) desperately begging the person in charge for them to accept it.

Making a Work Appealing for Animators

There are several underlying reasons why we’ve had 30-odd years to get to know Lupin. It really matters that the original creator, Monkey Punch-shi, has said, “The art will change as the people do.” and that, when it comes to animation, “Interpretations will vary from person to person.”

It’s also hard to ignore the sheer number of talented animators who have been involved in its production at some point. There are those who have represented anime as a whole, people like Miyazaki Hayao, Takahata Isao, Dezaki Osamu, Yoshikawa Souji, as well as Kitahara Takeo-shi, who oversaw the renewed character designs, and part 3’s Aoki Yuzo-shi.

But most important of all, I suppose, is the fact that the series itself makes animators think, I want to try! and I want to make it move!

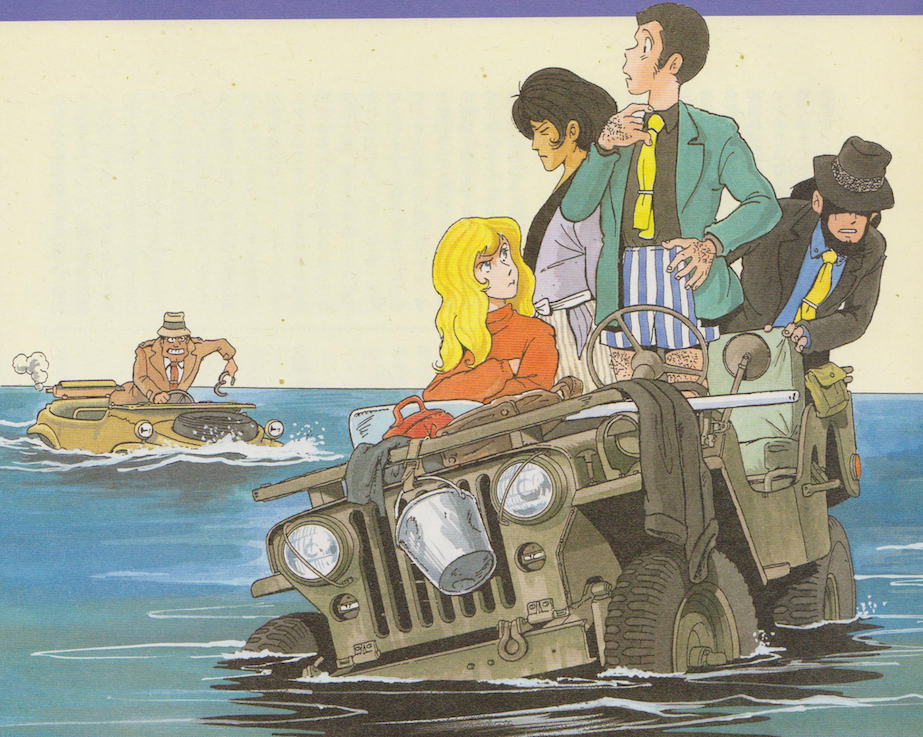

What appealed to me about Lupin, what got me attached, was that it was a vessel I could pour my interest in things like cars and guns into by animating them. Back in the Toei Douga days, we were always working on things like Shonen Sarutobi Sasuke, Saiyuuki, and Hakujaden. So I wasn’t the only animator back then who felt like the whole Lupin project was particularly atypical and refreshing. I think that much should be evident from the sheer bounty of talented animators who have been involved with it.

Then, how can we guarantee Lupin will continue to shine on into the future…? I think we’re facing a major crossroads. Certainly, the franchise has been embraced by a massive army of fans and can thus count on high levels of support. But I worry that the production side may, as a result, end up making too-safe choices, valuing the status quo, and fearing a mistake. In doing so, I must worry that they may overburden the creators with demands during production, spoiling chances to add new angles to Lupin’s charm. We’ve also got our work cut out for us with the voice actors. What will happen next? Will we be able to renew the roles, discover new, appealing people to play them?

Studio Ghibli has been able to turn out world-renowned works one after the other precisely due to the acumen shown by Tokuma Yasuyoshi (Founder of Tokuma Shoten/Deceased) and Suzuki Toshio (Company President of Studio Ghibli). I want young producers to foster a similar eye for young talent. I don’t necessarily think that the current producer-centric method of anime production is bad. Still, I pray that when they find people with the talent to create new possibilities for anime, they’ll have the courage to put those people in charge and step aside.

I believe that’s an essential requirement for giving Lupin a new charm, giving it a sense of true permanence.

Translation: Andrew Gallagher

Translator’s notes:

[1]: Aoki Yuzo directed the TV series Lupin III: Part 3

[2]: A Production is the predecessor to Shin-Ei Animation. Osumi Masaaki came back to Lupin III to direct the Ansatsu Shirei TV special in 1993. Takahata and Miyazaki should need no introduction.

[3]: Tokunaga Motoyoshi is the founder and current president of studio The Answer. It was established in 2004 by former Walt Disney Japan staffers after staff cuts.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Do anime events have room for creators? – Interview with Koji Takeuchi

The Annecy International Animation Film Festival is a place of many little pleasures, and one of them is to meet with Kouji Takeuchi, a pillar of the anime industry, and learn a little bit more of Studio Telecom's lore, which you can read more about in our previous...

Takeshi Honda’s The Boy and the Heron – Long Interview

Nicknamed “Master” since his early days in animation, Takeshi Honda is one of anime’s greatest artists. After a brief period at the studio Atelier Giga, he spent most of the 1980s and 1990s at studio Gainax, where he worked on its most iconic productions:...

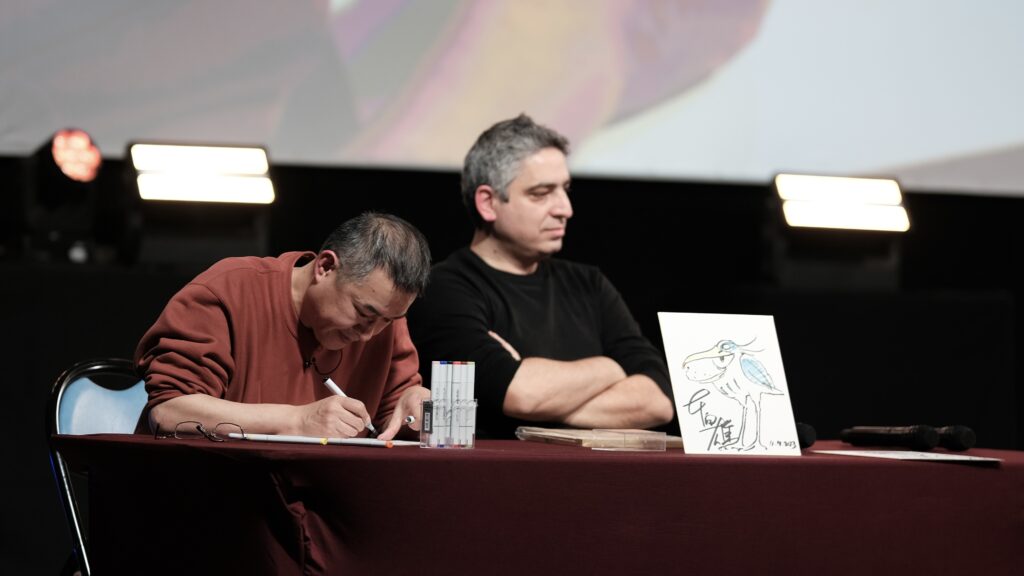

Who is Takeshi Honda, from Evangelion to The Boy and the Heron – Panel at Art to Play 2023

Takeshi Honda is a highly respected animator amongst anime fans, known for his exceptional work on several popular anime series, including Hideaki Anno's Nadia: The Secret of the Blue Water and Neon Genesis Evangelion, and Satoshi Kon's Perfect Blue, and Millenium...

Recent Comments