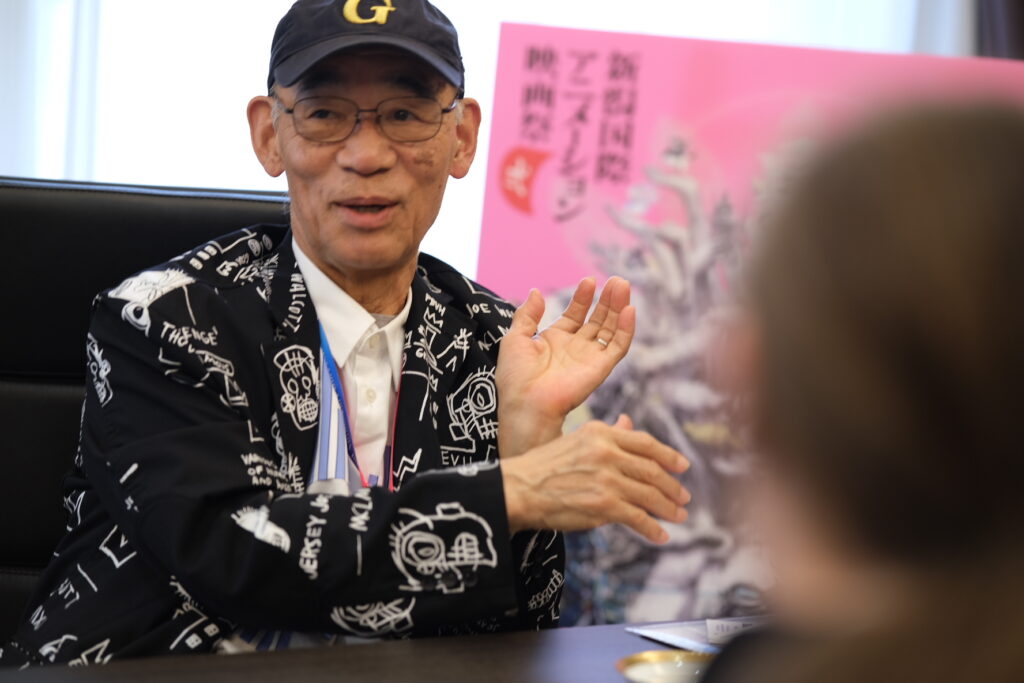

Nicknamed “Master” since his early days in animation, Takeshi Honda is one of anime’s greatest artists. After a brief period at the studio Atelier Giga, he spent most of the 1980s and 1990s at studio Gainax, where he worked on its most iconic productions: Gunbuster, Nadia, and Evangelion. After his departure, he worked with some of the greatest names in the industry, such as Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii.

Honda’s status only rose with the announcement that he would serve as animation director on Hayao Miyazaki’s latest feature, The Boy and the Heron. Honda’s presence in the movie can be strongly felt, and we were very curious to know more about it when we discussed its production with two of its animators, Toshiyuki Inoue and Akihiko Yamashita. Then, we learned Mr. Honda would attend an event in France, the Art to Play convention in Nantes, Brittany. Meeting him was a matter of course and, after much effort, we managed to spend over an hour with him. It was an incredibly entertaining conversation, full of insights on The Boy and the Heron and Honda’s art and career.

This interview is brought to you through a partnership with Animeland, France’s first anime and manga magazine

This article would not have been possible without the help of our patrons! If you like what you read, please support us on Ko-Fi!

This interview is available in Japanese. 日本語版はこちらです

“The film had barely started, and we were already changing things!”

Last month, I listened to the recording of the Animestyle event dedicated to Kazuchika Kise and Tetsuya Nishio. You appeared at the end and said you’d like to talk more about Tomonori Kogawa[1] and Space Runaway Ideon. I’d be very happy to oblige, but I’m afraid we have to talk about The Boy and the Heron first…

Takeshi Honda: (laughs) No problem!

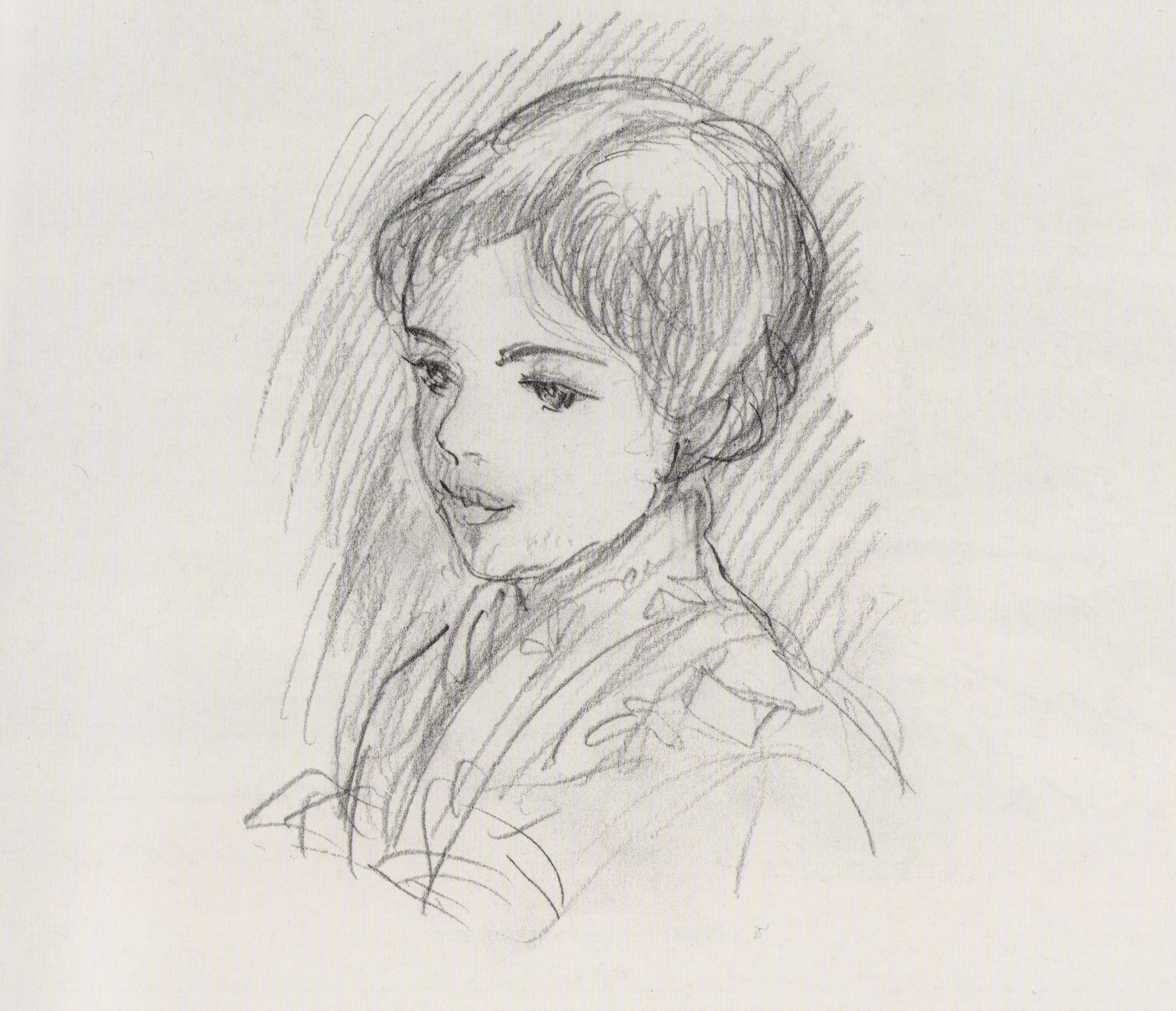

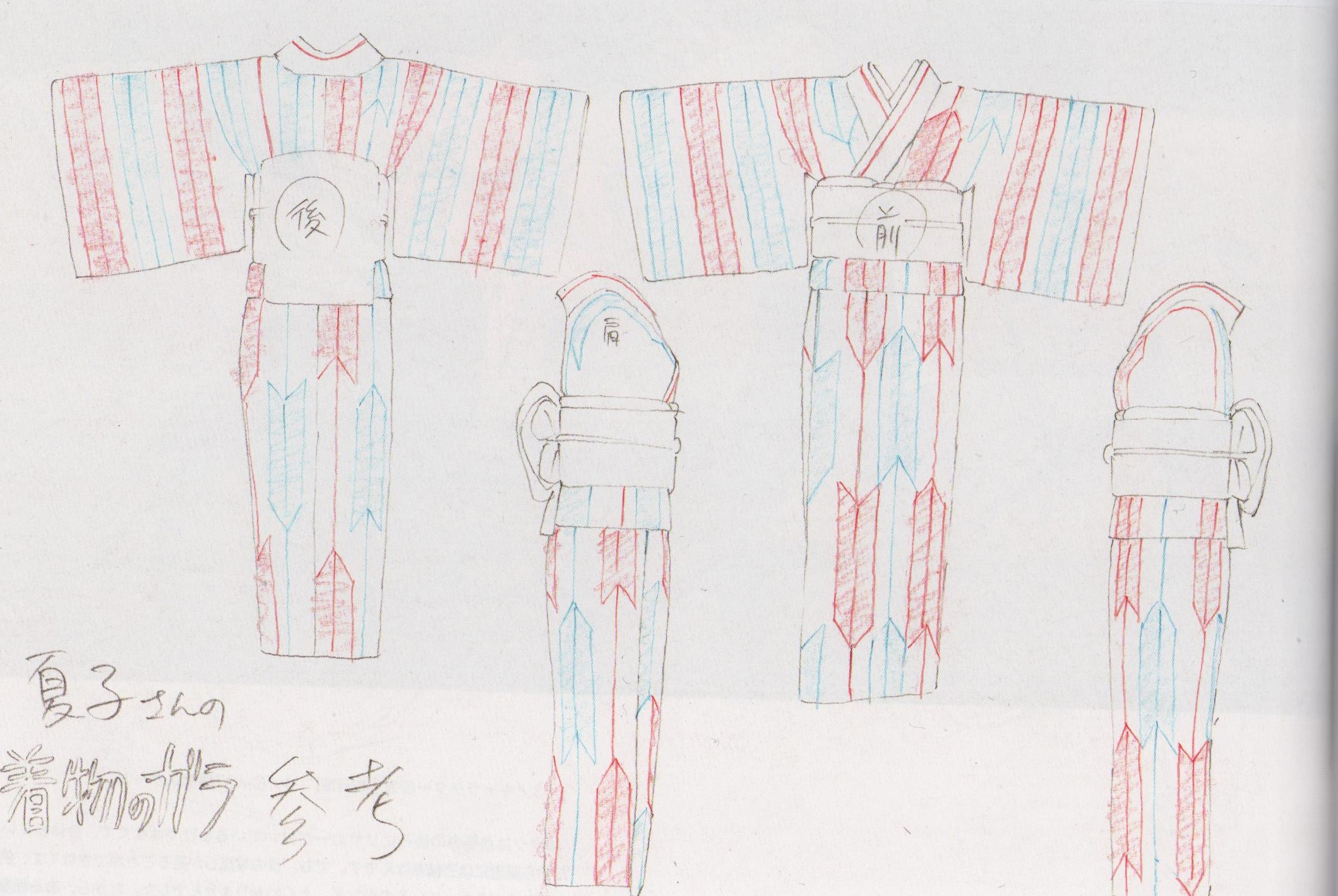

So, first, according to Toshiyuki Inoue[2], Natsuko is the only character for which you didn’t just clean up director Miyazaki’s rough but did the design entirely on your own. Why is that?

Takeshi Honda: That’s right. The reason is that there was only one rough, which was really rough and impossible to use as is. The pattern of the kimono wasn’t settled; Miyazaki had drawn without really thinking about it.

Why is that? Was Natsuko a difficult character for Miyazaki?

Takeshi Honda: Well, at the beginning, Miyazaki used a novel, The Book of Lost Things, as a base. I read it as well, by the way. There’s a character who more-or-less matches Natsuko, but she’s a bit unstable psychologically, and the impression she gave off wasn’t right. But on my end, I just drew Natsuko’s design as I imagined it from the book. I showed that to Miyazaki, and he immediately approved it.

Ah, I see. I was right to think that it’s entirely your character! When I first saw her, I thought she could be an Evangelion character…

Takeshi Honda: (laughs) Miyazaki seemed quite satisfied with my design, but as the actual animation began, we started making quite a few changes. On Miyazaki’s films, the reference drawings are ultimately just there to settle on the colors and nothing more.

I see. So, more concretely, first you did the reference drawings, then as the key animation and supervision work progressed, you did your own changes?

Takeshi Honda: Right, Miyazaki’s initial drawings, which are used to decide the colors, are the most important. But in many cases, the actual style changes at the layout stage.

See Mahito in the station scene: his hair wasn’t meant to be as long as first. When he takes off his hat in front of Natsuko, Miyazaki wanted his hair to get ruffled in the motion. But to do that, we had to make the hair longer, and the character looks different from the actual references! I was pretty surprised; the film had barely started, and we were already changing things! (laughs) I must say that it kinda wracked my nerves at first.

It mustn’t have been easy for the staff who joined later either: I had to tell them to draw something different from the actual reference…

Regarding these changes, the two scenes you drew with Natsuko look pretty different. The station scene is in your usual style, very sharp and just like the reference, but the delivery room scene looks nothing like it.

Takeshi Honda: Even though I animated these two scenes, there were actually 3 or 4 years between the two. So, of course, my own style changed over the course of such a long time…

The other thing is that, with beautiful women, the hair is very important: if the hairstyle changes, the overall impression completely changes as well. In the station scene, Natsuko’s hair is properly made, but in the delivery room, it’s all loose. The impression it gives isn’t the same, and it was impossible to return to the initial image. Miyazaki understood that very well, and I think it makes sense story-wise.

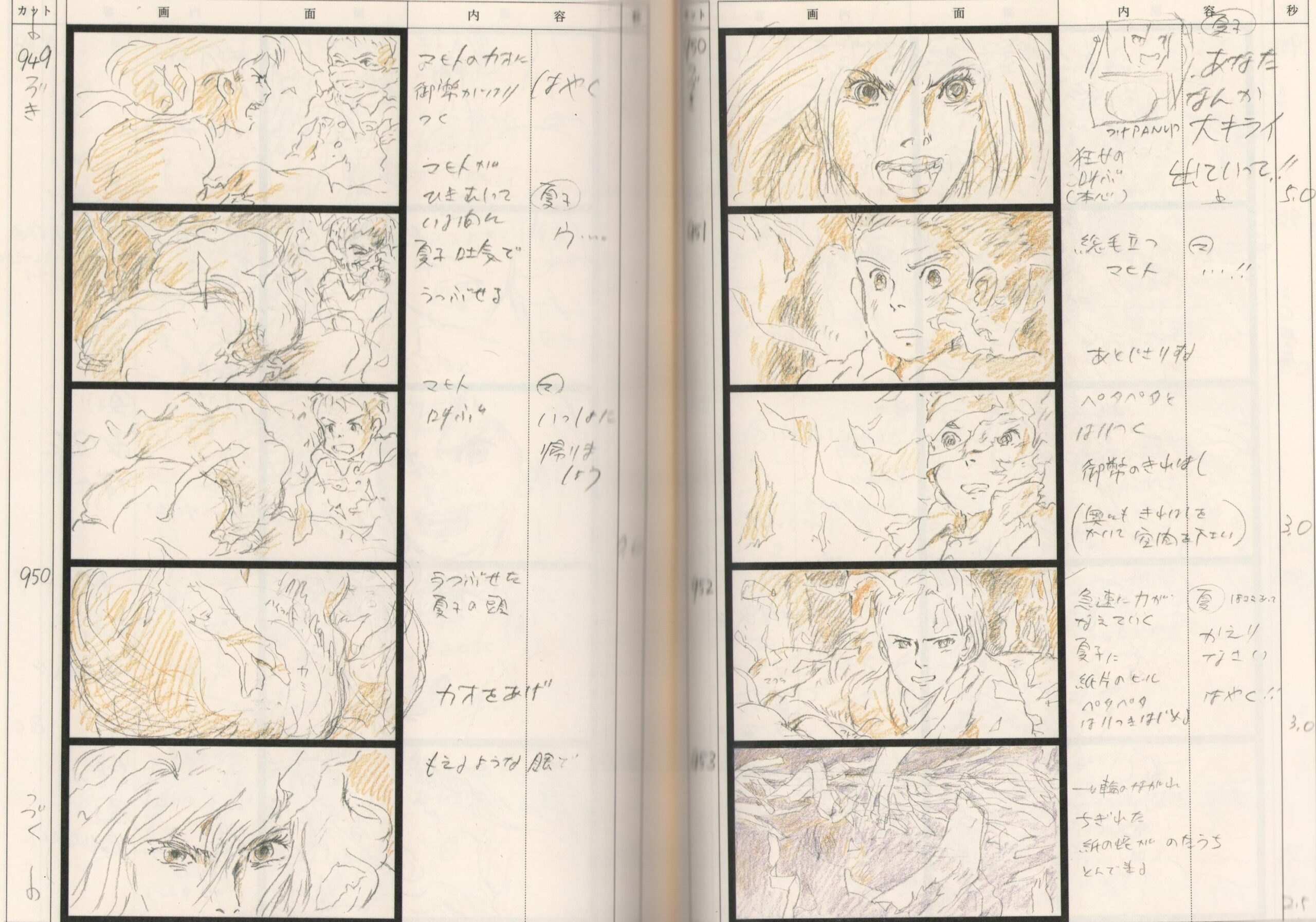

Miyazaki’s own storyboards for these scenes look quite different. In the first case, Natsuko is drawn with somewhat round, soft lines and looks beautiful, whereas in the second case, she’s wild and scary. Your own drawings are different from the storyboard: she almost doesn’t look like a human being in the storyboard…

Takeshi Honda: Ah, yes, that’s just it.

But your animation is much cleaner. The reason it’s scary is because it’s so realistic. A bit like Patlabor 2[3], in a sense…

Takeshi Honda: Aah, there might be some of it.

I did that scene towards the end of the production, so it felt like anything would go. (laughs) Also, there are a lot of close-ups on the face, right? In animation, you must be very careful with shots like that: if there’s too little detail, the linework doesn’t hold, and the overall image collapses. So I had to make it realistic so there would be more detail… And in the end, it looks completely different! But really, I didn’t really care anymore at that point! (laughs)

I believe you weren’t supposed to do the key animation for this scene at first…

Takeshi Honda: That’s right. It was originally Eiji Yamamori’s animation…

Why did you decide to redraw it?

Takeshi Honda: Well, Yamamori’s drawings were scary as intended, but a bit too much – it turned repulsive. He went a bit too far. For me, a maternal character like Natsuko couldn’t be repulsive. I thought she should rather look devilish, as in the storyboard, and that’s why I made corrections.

Maybe not “repulsive”, but there are some disgusting scenes in the film, aren’t there? Like when the heron shows up with teeth, or when the fishes and frogs come out… All of that was pretty good.

Takeshi Honda: Yes, I think these worked out pretty well. At first, the heron was supposed to feel gross, and I think he really is. That part with the teeth you mentioned was by Takayuki Hamada, a former Telecom animator. Then he moved on to Studio Chizu, where he worked on Summer Wars – he did the meal with all the family. It’s absolutely incredible.

“Miyazaki doesn’t like settling on everything beforehand”

So in that sense, the staff really came from everywhere: you were a Khara employee during the production, Mr. Hamada was from Chizu…

Takeshi Honda: Right. Hamada’s a Ghibli employee now, though. Inoue as well…

Just like you, right?

Takeshi Honda: Yes.

I believe your and the Ghibli veterans’ approaches were somewhat different. Everybody says Miyazaki and the Ghibli people draw with their instinct…

Takeshi Honda: I guess that’s what people say, but I don’t think they totally do. I’m sure they decide some things before they actually start drawing. It’s just that Miyazaki doesn’t like settling on everything beforehand. Usually, when you do a layout, you start with the vanishing point and vanishing lines to get the perspective right. But Miyazaki gets angry when he sees layouts like that! He says it makes the drawings go bad or something. That’s what he says, but you just can’t do without the vanishing lines whenever you have a character moving into depth. So I’m sure he does them in one way or another.

Anyways, even if Miyazaki’s layouts aren’t always perfectly correct, they’re extremely flexible and easy to use.

With that in mind, would you say you’ve got a more logical approach?

Takeshi Honda: I wouldn’t go as far! (laughs)

So, for example, compared to Toshiyuki Inoue…

Takeshi Honda: Inoue’s on a completely different level! He’s the best animator in Japan, after all…

Going back to that difference in approaches, did it cause any difficulties in communicating with the Ghibli veterans?

Takeshi Honda: Right, but there were some great people: for instance, Katsuya Kondô[4], who’s incredibly good and fast, he helped me out a lot. Also, people like Atsuko Tanaka[5] or Takeshi Inamura. I really realized how good all the Ghibli people are.

Ah, I wanted to ask about Ms. Tanaka! She’s famous for her food scenes, so did she animate the one where Mahito eats bread and jam this time?

Takeshi Honda: Actually, this scene is by Akihiko Yamashita[6].

Or rather, it went through a lot of people. At first, it was Hideki Hamasu, but Miyazaki redrew it all and then sent it to Yamashita.

So that’s why this scene is so lively! It’s really expressive; that’s pure Miyazaki…

Takeshi Honda: Right. Miyazaki really put a lot of effort into this scene. Even after he left the final touches to Yamashita, there was still something bothering him, so he redrew it again. It feels like we were just there to clean up his drawings. (laughs)

Overall, did Miyazaki make a lot of corrections like that?

Takeshi Honda: He’d do a lot of corrections at first. But he did less as it went: towards the end, when the Parrot King appears, he let most drawings pass. He didn’t touch Inoue’s drawings, for instance. But well, I had nothing to correct on those myself. They were already perfect as they were!

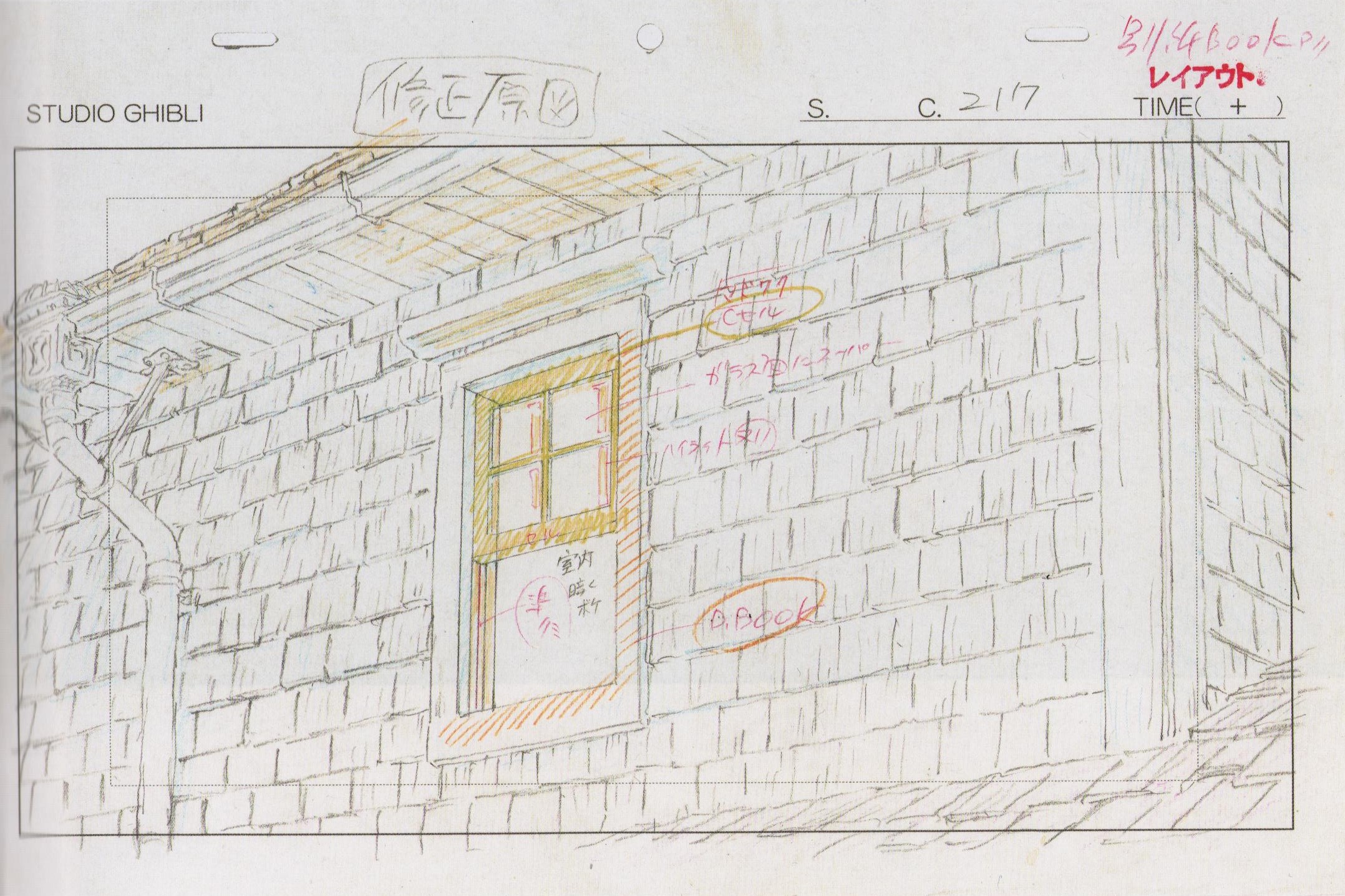

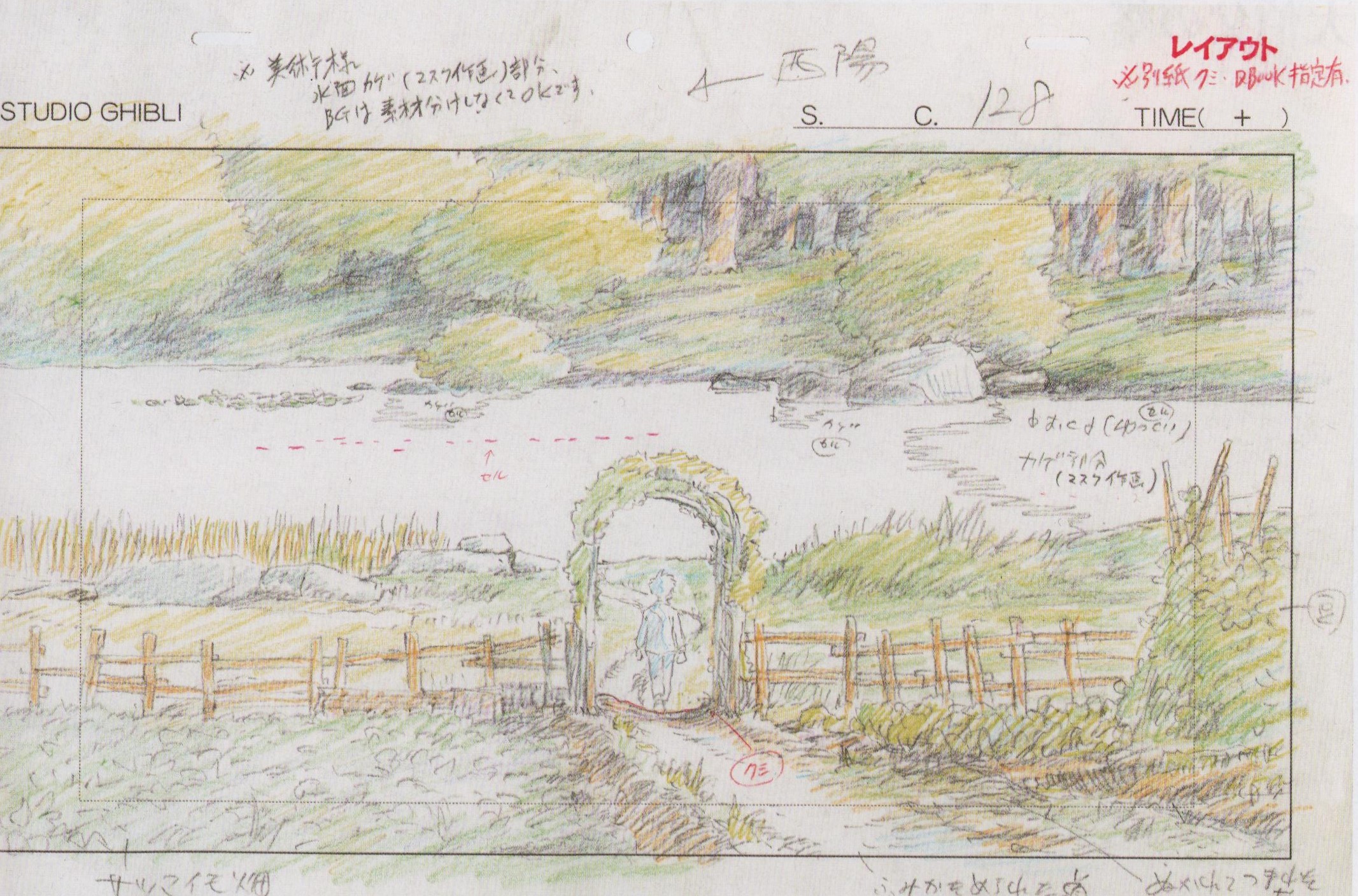

That’s Mr. Inoue for you! In the Art Of The Boy and the Heron, many layouts are attributed to Miyazaki himself. For instance, this one from the scene when Mahito tries to close the window of his room, and Natsuko helps him out. Did Miyazaki do such layouts from the start himself?

Takeshi Honda: (Looks at the layout) Hmm, this is probably Yamashita’s layout. And then I’d say Miyazaki drew on top of it?

So he kinda cleaned up the animators’ layouts?

Takeshi Honda: I wonder… Looking at this layout, only Yamashita would write that many annotations. (Flips through the book) But for this one, where Mahito is heading towards the pond, the writing is Miyazaki’s.

In general, he’d add details on top of the animators’ drawings.

Miyazaki didn’t just do that, but also some rough key animation: that’s the reunion between Mahito and Himi at the end. Did he do it all himself?

Takeshi Honda: Yes, the layout and keys.

Did you ask him to do that scene, or did he decide to do it himself?

Takeshi Honda: He decided by himself. Then, Takayuki Hamada cleaned up his keys.

Were you brave enough to correct Miyazaki’s drawings?

Takeshi Honda: Actually, I didn’t know if it was ok at first. But correcting the drawings was my job, wasn’t it? So I hesitated, but in the end, I went and did it. I only heard afterward that you’re not really supposed to do that… I wish I had been told that sooner! (laughs)

Going back to your own process, I’d like to know how you decide on the timing for your animation…

Takeshi Honda: Hmm, I’d say that I begin with the drawings rather than with the timing. So, first, I imagine the movement and start from the most important poses. It’s easier that way. Then, once I’ve got the overall flow, I progressively fill things in with more detailed intermediary drawings, and it’s only at the very end that I decide on the timing while using a quick action recorder.

About that, when we talked to Mr. Yamashita, he told us Shin’ya Ohira[7] doesn’t use an action recorder…

Takeshi Honda: Ah, that must be because he works from home. That might explain why he wouldn’t use one.

Is that so? Mr. Yamashita told us it’s because he’s a genius!

Takeshi Honda: (laughs) Ohira’s a veteran, after all.

I had a similar experience with Yamashita back when I first entered an anime studio, Atelier Giga: he got me depressed. He was only two years older than me, yet he was already so good! Even today, I don’t think I’ll ever be able to catch up to him.

“I got kinda angry at Miyazaki at some point!”

Ah, I wanted to ask about that, but let’s keep it for later. Although The Boy and the Heron is both yours and Miyazaki’s film, I didn’t feel any eroticism in the drawings…

Takeshi Honda: Yes, I restrained myself. I was afraid Miyazaki would get angry at me if I went down that way! (laughs) It’s not really his thing…

Really? There can be something erotic in his films…

Takeshi Honda: That’s right, but it applies to his older works. Women could be pretty sensual… But he’s lost interest in this kind of stuff now.

The Oedipus complex is a pretty big theme of the film, though.

Takeshi Honda: Yes, but that’s precisely it! Because it’s about the Oedipus complex, if things became too erotic, it would have been too much.

For instance, when Natsuko says “I hate you!” to Mahito in the delivery room scene, I initially wanted to open her kimono and show her chest. But it would have been going overboard, so I gave it up in the end.

Ahh, that’s a shame… (laughs)

Takeshi Honda: Well, since she’s wearing a kimono, she’d be naked under. But I preferred to keep it safe!

I see. (laughs) It’s perfect that you mentioned kimonos because I wanted to talk about that. With Millenium Actress[8], you’ve become an expert in drawing them, haven’t you?

Takeshi Honda: Millennium Actress was the first time I had to draw kimonos. Thankfully, in her kimono scenes, Chiyoko doesn’t move a lot, so it was okay. However, this time, Natsuko moves quite a lot, making it pretty difficult. The arrow pattern on her kimono is particularly complex as well, and that didn’t help one bit.

On Millennium Actress as well, the pattern on Chiyoko’s kimono was pretty complex, and this time, I could rest on that experience: back then, I did a dedicated reference sheet for the kimono pattern, and I made one as well this time. Without something like that, it would have been pretty much impossible.

On The Wind Rises, the clothes look pretty thick and stuffy, but this time, it is different. There’s more focus on creases and shadows…

Takeshi Honda: In previous films, the clothes looked like they were padded, but as we just discussed, if we did that for Natsuko, it might have ended up a bit too suggestive… So, I was careful to make the folds of her clothes more realistic. But for the old ladies, I kept things as they were in other Ghibli films.

Also, in previous Miyazaki films – especially in Howl’s Moving Castle, actually – the clothes are somewhat shiny as if they were wet. But there’s none of that this time.

Takeshi Honda: That must be because I didn’t do anything on Howl! (laughs) I wasn’t influenced by that.

I see. (laughs) Apparently, there were some disagreements between Miyazaki and you regarding the visual style…

Takeshi Honda: Is that so? Not really.

But I guess you didn’t always have the same opinion on everything?

Takeshi Honda: Right, but I was the one who had to adapt to Miyazaki and not the other way around, so in that sense, we never really “disagreed”.

Rather than that, there were times when Miyazaki would start correcting the drawings on some scene and approve all the other stuff that was submitted to him at that time, which could be pretty long. He’d even approve things that really shouldn’t have been. But he really didn’t change his mind, and I must say I got kinda angry at him about that at some point, like, “Shouldn’t you correct these instead?” (laughs)

Wow. So I guess that, in the 6 or 7 years the production lasted, your relationship with Miyazaki really changed.

Takeshi Honda: Yes, I’d say we became rather close.

Did you get the courage to submit your own ideas to him?

Takeshi Honda: Rather than that, sometimes I simply needed to hear his opinion, so I had to go talk to him and listen to what he had to say. He didn’t get angry or anything, so there was no problem on that front. I just drew things as I imagined them and got his feedback. There was no difficulty whatsoever.

Would you have debates or more intense talks?

Takeshi Honda: No, we wouldn’t really have big talks. Back in the day, Miyazaki and Mamoru Oshii would have these big arguments all the time, didn’t they? And, well, their relationship ended up breaking down… I’m not the type to get into this kind of stuff, so I didn’t have to restrain myself or anything. I was especially careful not to talk about politics! (laughs)

“Dreaming Machine was no good without Kon”

(laughs) And after 6 years or so you spent sitting next to Miyazaki, don’t you start wanting to do some direction yourself?

Takeshi Honda: I can’t speak for the future, but above all, I realized how difficult the director’s job is, especially with Miyazaki’s way of doing things. It impressed me to see how intense he could get at his age. While working on the storyboard, he’d check the layouts and also work pretty closely on deciding the colors. He always had to be somewhere, but he still managed to sit at his desk to check the layouts and animation. It’s really something, the way Miyazaki works.

That’s what makes it so interesting, isn’t it?

Takeshi Honda: It is, but I can’t do anything like what Miyazaki does.

Mr. Yamashita, Mr. Inoue, and you are now Ghibli employees. I suppose that means you’ll be on Miyazaki’s next work. This is a pretty difficult question, but Miyazaki is getting old. If he can’t complete his next film, what are you going to do?

Takeshi Honda: If Miyazaki can’t direct anymore, if he finally retires for good, I don’t think Studio Ghibli would just stop. I’m sure the course of action in such a case has been considered. I don’t think production would just suddenly stop.

But in my case, if I had to leave Ghibli, I wouldn’t have too many problems finding a job. There are a lot of studios in Japan, lots of people I could help out… But I’d like to stay at Ghibli as long as I possibly can, as long as Miyazaki himself hasn’t decided on things for good.

Nobody would want it to become like another Dreaming Machine[9], after all…

Takeshi Honda: Well, in Dreaming Machine’s case, the storyboard wasn’t even complete. Masao Maruyama, the president of Madhouse, tried to continue the project after Kon died, but business circumstances made it way too difficult. Maruyama had to spend I don’t know how many millions of yen to get the rights back: when he left Madhouse to create MAPPA, he wanted to resume Dreaming Machine, but Madhouse told him they had invested so much in it, and he had to pay them back to obtain the rights even though Maruyama created Madhouse in the first place!

The other problem is that there was no script either. In the middle of Dreaming Machine’s production, Kon just disappeared. He didn’t tell the reason to anyone – he had pancreatic cancer, but I don’t think anybody knew except the production staff closest to him. Maruyama didn’t know any of it and got really angry. He went to the producer’s house in a rage, asking what Kon was up to, and that’s where he heard the news.

At that point, it was too late for Kon. Maruyama went to his house and couldn’t even get out of bed. He just cried and said sorry. That’s when Maruyama promised he’d take over the project and see that it would be completed. But there was no script, so Maruyama had him record one on his deathbed… According to the person who was supposed to take over direction, you can hear Kon’s groans of pain, and it’s pretty tough to listen to.

In any case, I think that it was no good without Kon. It was too difficult. Maruyama tried his best, but Nippon TV bought Madhouse, he left the company, and there was nothing he could do anymore. It’s really a shame it ended up that way.

“Miyazaki would never explain the references”

Going back to How Do You Live… It seems Miyazaki talked about himself and showed you pictures of his family, but did he explain anything to you regarding the movie’s messages and themes?

Takeshi Honda: No, he didn’t really explain anything. Same for the pictures: he only showed me pictures of his father after I completed the design! Couldn’t he have shown that earlier? (laughs)

Do they look similar in the end?

Takeshi Honda: Not at all! The vibes they give off are completely different!

But there were still real models for the characters: Kiriko is Michiyo Yasuda[10], the heron is Toshio Suzuki… Did Miyazaki ever talk to you about that?

Takeshi Honda: That’s the kind of thing Miyazaki would never talk about. But he did say pretty often that Kiriko was just like her. Even though she didn’t really look like that…

Really? She looked neither like the young nor the old Kiriko?

Takeshi Honda: Like neither! It’s just the image Miyazaki had of her, I guess. He just said, “It’s Yacchin” all the time. But I personally never met her, so…

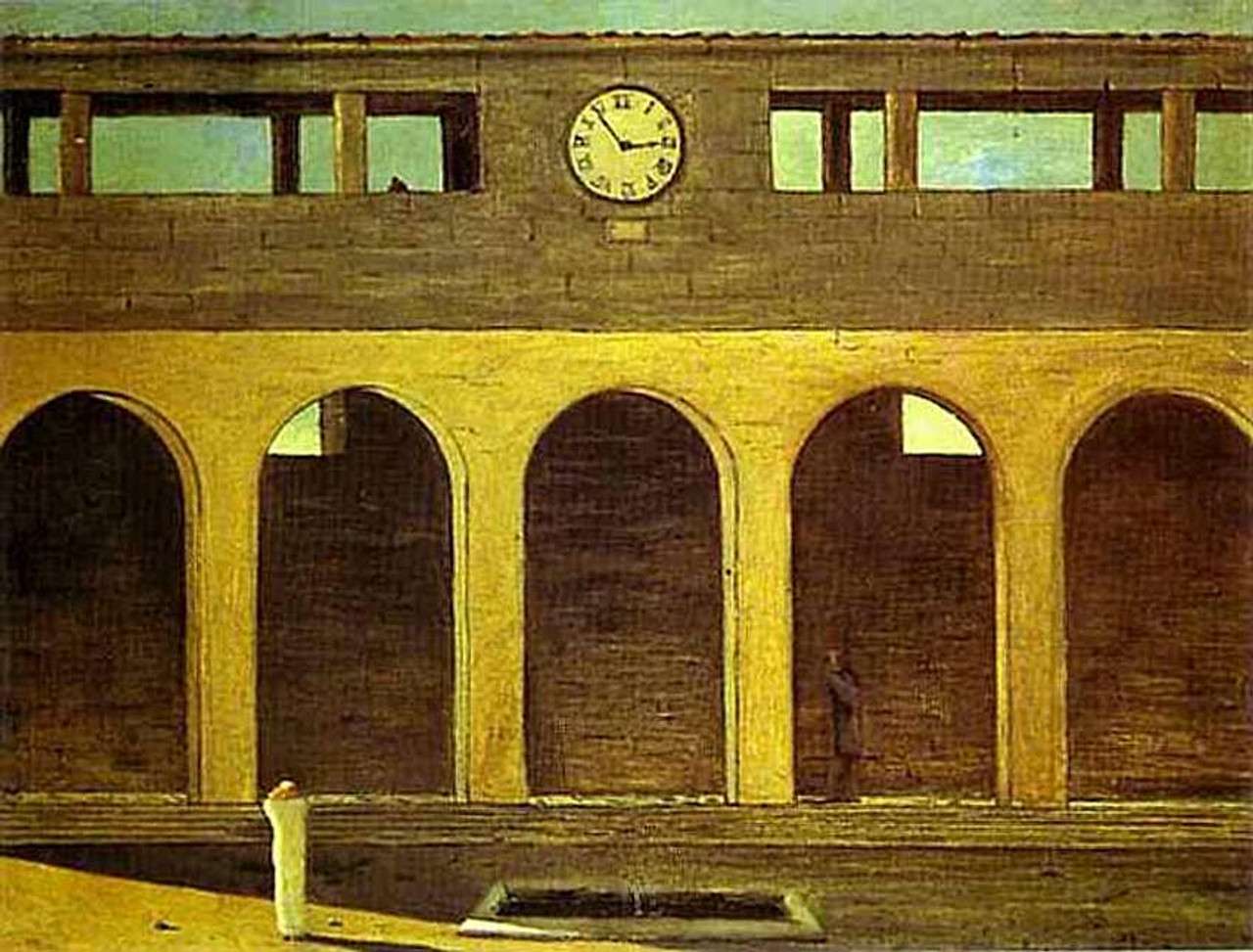

Don’t you know if she liked the painter Chirico?

Takeshi Honda: Chirico?

The Italian painter, Giorgio de Chirico. The room where the great-uncle is looks a lot like one of his paintings…

Takeshi Honda: Ah, that’s true. You’re right, Miyazaki totally referenced it.

But he never mentioned it to you?

Takeshi Honda: He’d never explain these kinds of references.

If he didn’t say anything, everybody must have thought “Kiriko” was a reference to Votoms…

Takeshi Honda: (laughs. Then, in a very serious tone) Ah, that’s the first time I’ve heard about this. I can’t say too much, but you might be onto something.

(laughs) There’s also The Isle of the Dead…

Takeshi Honda: Ah, this one was indicated in the storyboard about the island of the Wara-wara where Kiriko lives.

Oh, that’s right! But nothing from Miyazaki himself?

Takeshi Honda: Well, that painting’s really famous, so I recognized it immediately…

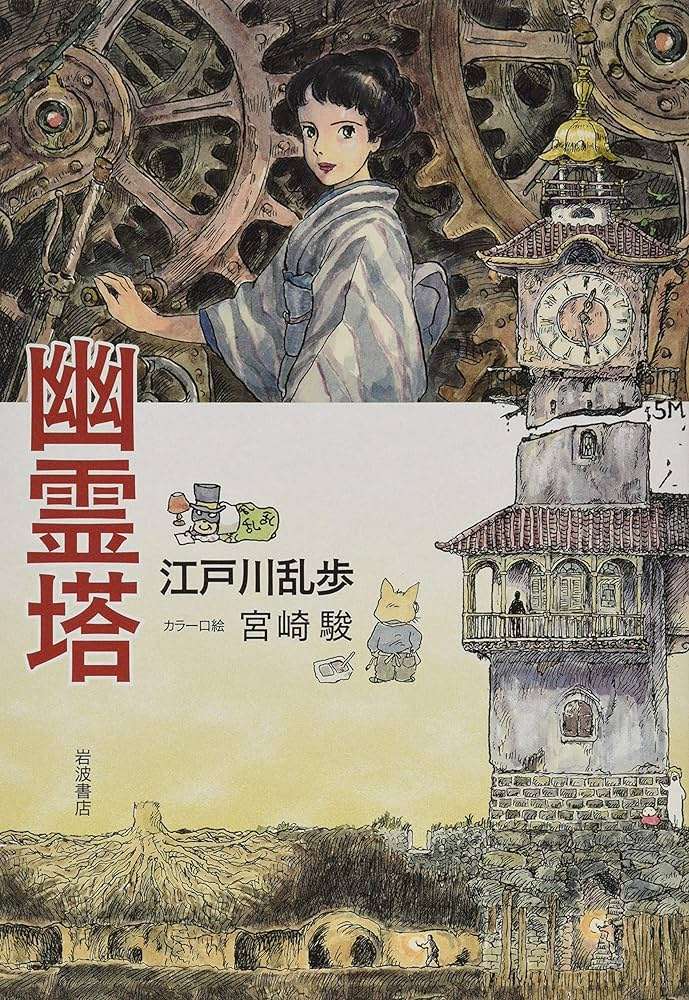

There are a lot of other references… For instance, Edogawa Ranpô’s Ghost Tower…

Takeshi Honda: Really, no explanations whatsoever! But when we talked, Miyazaki mentioned that he liked Ghost Tower when he was a kid.

Do you know about the cover he did for it?

Takeshi Honda: I do.

Don’t you think it looks like the tower in the movie?

Takeshi Honda: That’s right, but more than that, I think Miyazaki likes putting towers in his films!

So, since Miyazaki didn’t explain a lot of the references or themes, was he very technical when talking with you or the staff?

Takeshi Honda: Well, rather than getting into the technical nitty-gritty side of things, he tends to say what kind of feeling or vibe he wants. So it’s during the meetings, when he gets like that, that he goes “with his instinct,” as you said.

At the time of the Ghibli Museum short Mr. Dough and the Egg Princess, he would speak in onomatopoeia, say stuff like, “Here, it goes dadadadan!” (laughs) Everything tends to be properly laid out in the storyboard, so he tends to explain the atmosphere he’s going for during the meetings. I guess things were similar on The Boy and the Heron. Of course, he’d explain things when asked, but most of it is written in the storyboards. Not a lot of people write down things in that much detail.

Actually, when we spoke to Mr. Inoue, he told us that, while Miyazaki’s storyboards are detailed, the specifics of the acting or performance aren’t specified that closely. What do you think? The compositions and camerawork are very specific, but in terms of animation, is he the kind to let animators free?

Takeshi Honda: He totally is. But he might redraw everything afterward… (laughs)

What about Satoshi Kon? His storyboards would be used as layouts… On the other hand, Miyazaki might give the impression he gives you freedom, but if he’s going to redraw everything in the end, are the animators really free?

Takeshi Honda: No, we really are!

As for Kon, at the time of Perfect Blue and Millennium Actress, he’d do storyboards the usual way and then completely redraw everyone’s layouts when he received them. But that took a lot of time and effort. So, from Tokyo Godfathers onward, he started using the storyboards as layouts. That’s why his storyboards from that time are so detailed. He’d do them with a computer, draw the backgrounds and characters properly, separate them, and use the result for the storyboard. Then, during meetings, he’d say, “The layouts are already completed, please start from the key animation.” That’s how he worked.

How about Hiroyuki Okiura[11]?

Takeshi Honda: Okiura’s boards are very clean and detailed, but they’re normal storyboards – he doesn’t enlarge them like Kon did. So he’s the kind to do things the usual way and then ask for retakes or redraw things himself if the layouts and animation aren’t as he wants. That’s why he always takes so much time.

“Miyazaki came and said, ‘I’m redoing everything’”

I see. Let’s go back to Miyazaki. According to Mr. Yamashita, the meetings with him are always so interesting. Can you tell us what kind of things were discussed?

Takeshi Honda: The meetings, huh… I think I forgot all of it! (laughs)

So, let’s take an example. How was the discussion for the delivery room scene? There was you, Miyazaki…

Takeshi Honda: There were the two of us, the animator Yamamori, the director of photography Atsushi Okui, the art director Yôji Takeshige, and the background artist Noboru Yoshida. I guess meetings were always like this.

And you didn’t get into the technical details?

Takeshi Honda: No, not really. So, for instance, think about it like this. Miyazaki’s way of thinking is still the one from the analog days, where you couldn’t do a lot of stuff. So he’d expect Okui to share his own ideas on how such or such effect could be achieved. But Okui himself didn’t really talk during the meetings: first, he’d receive all the materials for a scene, and only afterward would he try some things out.

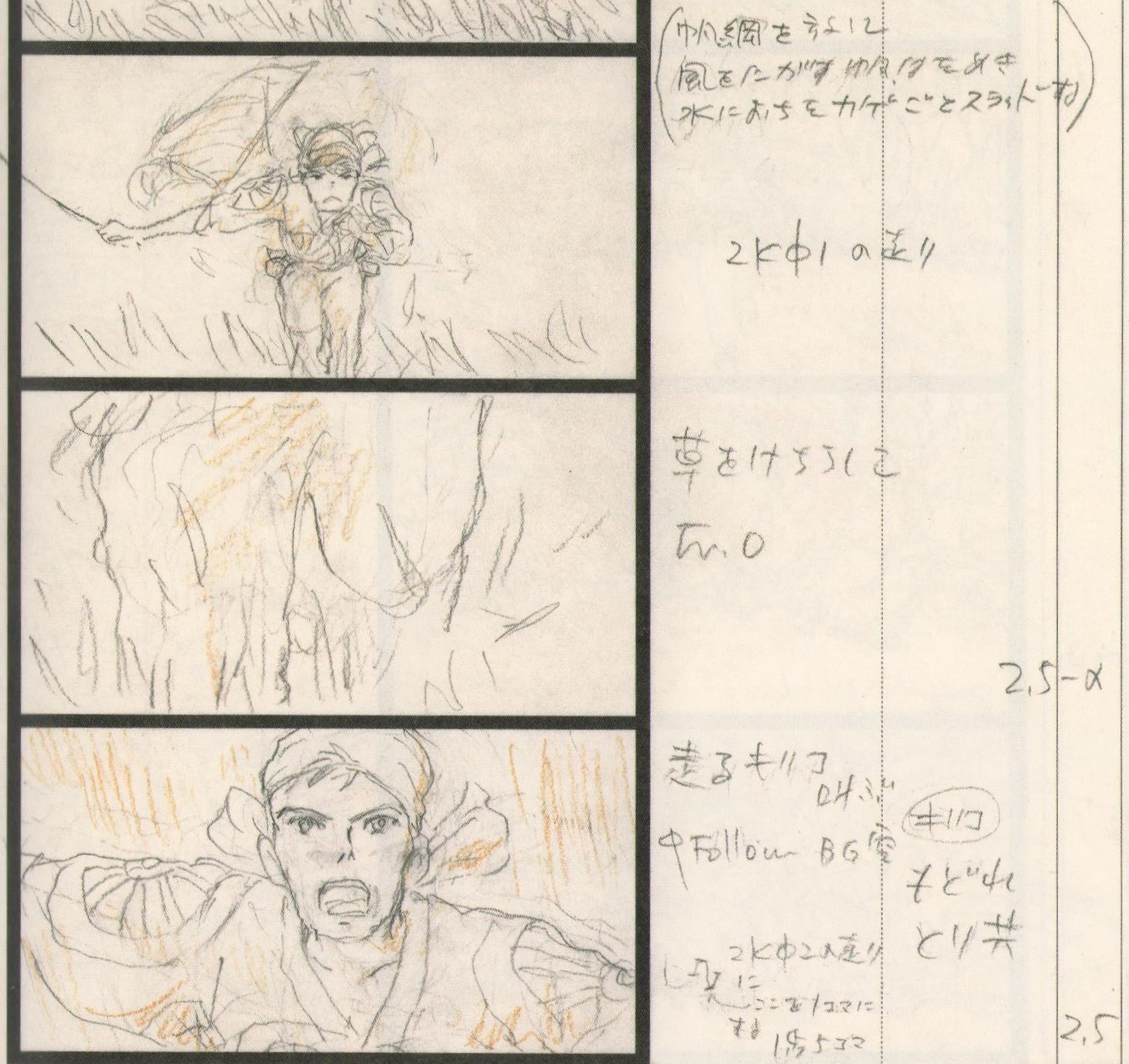

There are a lot of indications regarding the photography and timing in the storyboard itself. For instance, some movements are written down to the exact number of frames. Only Miyazaki goes into that detail, right?

Takeshi Honda: Right, there are a lot of indications about the photography in the storyboard. But the truth is that things in the film itself aren’t actually like that. It’s just that Miyazaki’s used to do things that way.

For instance, look at this cut when Kiriko runs to make the pelicans run away. In the storyboard, it’s written: “on 2s, an in-between for every key”. But we realized it’s too fast like that, so we added more in-betweens to slow things down. So, in that sense, many things are changed during production.

It also seems that Miyazaki hesitated a lot over the plot development of the C part, from when Mahito enters the other world. Can you tell us more about that?

Takeshi Honda: Yes, at first, Himi had Kiriko’s role in the plot. I was pretty happy that I’d finally be able to draw a Miyazaki heroine! But one week later, Miyazaki came and said, “I’m redoing everything. Everyone, give the storyboard back”. I was pretty surprised. Was he really going to redo everything? But then another week passes, and he comes back and says, “Alright, maybe that ‘everything’ was going a bit too far…” (laughs)

In the end, he mostly just put Kiriko in Himi’s place.

So that’s the only thing that changed?

Takeshi Honda: Yes, but there’s a reason for that. Himi is Mahito’s mother, right? So she’s smarter than Mahito and teaches him all kinds of things. But at the same time, she’s the same age as him. So, if she had been there from the start, it would have meant the girl took the spotlight – Mahito wouldn’t be the protagonist anymore. That’d have been pretty bad. So, I think that’s why Miyazaki changed things the way he did.

In Miyazaki’s image boards, we can also see that the design of the great-uncle changed quite a lot as well…

Takeshi Honda: Right. But I never saw that image board during the production!

Really?

Takeshi Honda: For real. I just drew the reference design from the storyboard. So, the design is really Miyazaki’s in the first place.

I believe Miyazaki’s quite the prankster. Do you have any fun stories regarding that?

Takeshi Honda: Well, Miyazaki really gets along with Noboru Yoshida, who’s a background artist. They’re really friendly with each other, so Miyazaki always had Yoshida behind him and called for him all the time, even when he wasn’t there! So I’d tell him, he’d turn back and go, “Ah, you’re right. Where did that guy go?”

They’re together all the time. Even when he goes to get a drink, Miyazaki takes him along. They took me with them sometimes as well… It was during one of these times when we were just having small talk that Miyazaki said he’d redraw the scene where Kiriko and Mahito cut the fish up. (laughs)

“Ohira’s style is invincible”

I have a question regarding the staff. There is someone called “Yumi Handa” in the animation credits, but that seems to be her first credit. Is she some new animator Ghibli recruited for the film?

Takeshi Honda: Aah, you mean Yumi Ikeda! She’s from Khara, but she always dreamed of working with Miyazaki, so I managed to get her on the film. I guess “Handa” is her husband’s name. You see when we register for the production, we have to write stuff like our name and address, and I suppose she wrote “Handa”. That must be why she’s credited that way.

What scenes was she in charge of?

Takeshi Honda: A lot of stuff all over the movie. The first meeting between Mahito and the heron: just after Mahito comes out of Natsuko’s room when the heron flies outside the window, and Mahito takes out his knife. Then, in the C part, when Mahito’s sleeping in Kiriko’s room, wakes up and goes out. Just after that, when he meets the dying pelican, is Katsuya Kondô. Also, there is a bit when the crowd of pelicans attacks Mahito in front of the grave.

Aah, yes, that part looks pretty difficult. There are so many pelicans. But that scene is by Hiromasa Yonebayashi, isn’t it?

Takeshi Honda: Right, she helped him out with some shots.

Mr. Inoue and Mr. Yamashita both told us drawing so many birds was hell. (laughs)

Takeshi Honda: I guess it was! But they’re so good at drawing birds…

Then, Ikeda also did the bit where Mahito enters the tunnel to meet the great-uncle – the first time, when he’s alone for the first time.

I see, thank you. There’s another animator I’d like to ask about: that’s Shin’ya Ohira. He was in charge of those scenes where you can’t tell if they’re real or nightmares. How was it decided to give him such scenes?

Takeshi Honda: Miyazaki had decided that at the very beginning. He’d say stuff like he wanted Ohira on such and such scene. The scene at the beginning has a lot of people in it; it’s pretty difficult. I guess that, for Miyazaki, nobody else could draw it.

As I just said, you can’t tell whether these scenes are reality or dreams. But for you, is Ohira still a realist animator?

Takeshi Honda: He definitely is a realist. But well, whatever he works on, he’ll never make any changes and always go with his own style. (laughs) It’s really tough to correct well, so when I got his drawings, I decided that, rather than correcting them, I’d just keep as much of his touch as I could.

In that sense, it’s a special film for Ohira, isn’t it? Usually, in Miyazaki’s films, he gets a lot of corrections, but this time, there are almost none.

Takeshi Honda: Almost none, indeed. But even in other works, even though Ohira might get corrected, you can still recognize him. Correcting him is useless: his style is invincible. You can try, but you’ll never kill it.

Ohira said it took him over six months to draw some shots. Do you have any idea which ones that might be?

Takeshi Honda: Maybe the first-person shot with all the firemen… But all the shots he was in charge of were pretty difficult. For example, the shot where the burning hospital collapses…

And he was also working on Pluto at the same time…

Next, I’d like to talk about Mr. Yamashita. I suppose he’s the animator you know best among the staff of The Boy and the Heron?

Takeshi Honda: Well, actually, we only spent six months together at my first studio, Atelier Giga. After those six months, the studio went bankrupt. We didn’t really work together in the 30 years after that. It’s just that, sometimes, I’d ask him to help out on some of my stuff – for example, Gonzo’s Blue Submarine No.6, or Evangelion, or Robot on the Road. In that sense, The Boy and the Heron feels like it’s the first time we’re really working together.

Yamashita was also the film’s assistant animation director. Were you the one to choose him?

Takeshi Honda: No, it wasn’t really my place to do so! Miyazaki would just give him the drawings he wasn’t satisfied with. Because I couldn’t handle everything on my own, and it would have just slowed everything down.

I see… You’ve got your own style, which is pretty different from both Yamashita and Miyazaki’s styles. In that sense, would it be reasonable to say that Yamashita acted as a sort of intermediary between you and the “Ghibli style”? Because he was there, the movie looks more like a normal Ghibli film.

Takeshi Honda: Hmm, it’s true that the scenes he was in charge of look more Ghibli… And I guess I was influenced by that in my own work.

“Kogawa’s always so considerate about the rest of the staff and the viewers”

Well, I guess that now it’s finally time to talk about Tomonori Kogawa! Many Pack and Atelier Giga artists were his disciples, after all… In your case, what kind of influence did you receive from him?

Takeshi Honda: Actually, I’ve never met Kogawa. Kogawa created Studio Beebow, and some of the people who left it created their own studio, Pack, which became Atelier Giga.

In terms of influence, I’d say it’s Ideon – I’ve loved the style of the drawings for a long time.

On Ideon, would you say you preferred Kogawa or Yoshinobu Inano[12]?

Takeshi Honda: Ah, I might like Inano best! What’s special about Kogawa is how he always cares to make his drawings accessible.

Have you ever used Kogawa’s animation manual?

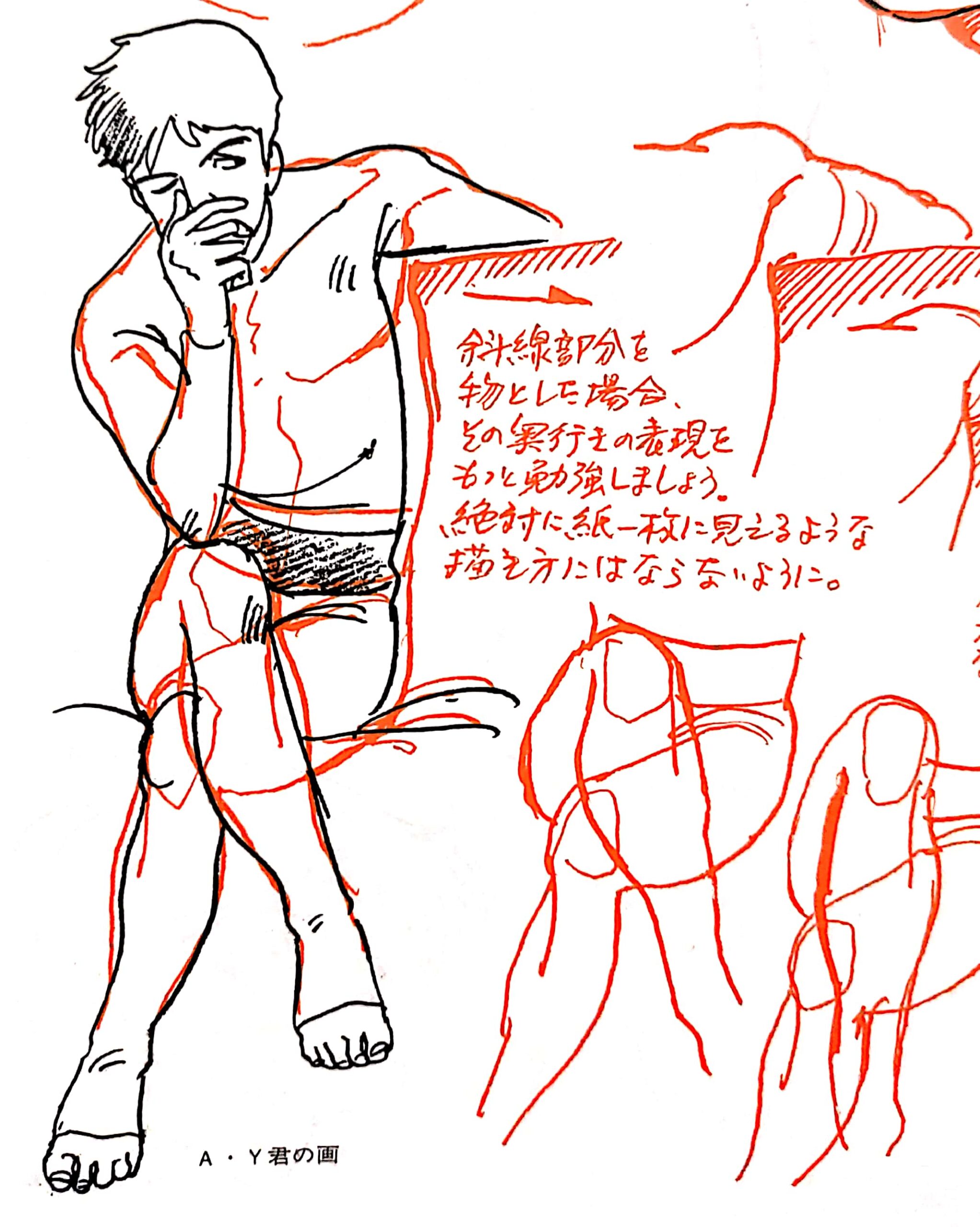

Takeshi Honda: Yes, I owned it at some point! But I have no idea where it’s gone now. (laughs) In particular, I looked a lot at the pages where he corrects the drawings of his disciples. (flips through the book) Ah, look at this one. It’s pretty easy to understand, isn’t it? And it’s written “AY”, right? The original drawing is Yamashita’s.

Ooooh, of course, AY – Akihiko Yamashita!

Takeshi Honda: Yamashita’s drawings are awesome, aren’t they? He was already that good back then! I don’t even know what you’d need to correct. It’s already so good…

Actually, I think Yamashita and Kogawa share the same view of animation. The way they’ll say that animation isn’t just about drawing accurately, that you must put some lies into it.

Takeshi Honda: Yes, I see. Kogawa’s animation is always easy to understand. It’s the same for Yamashita. Animation is a collective work, after all, so things must be simple – you need to think about the in-betweeners who’ll receive your drawings and all that. That’s definitely something Yamashita got from his master.

Many people seem to think that because Kogawa teaches animation and has a realistic style, he’s all about anatomy and logic, but he’s actually pretty different.

Takeshi Honda: That’s right. Well, I can’t tell because I’ve never met him, but you can see through his drawings that he’s always so considerate about the rest of the staff and the viewers. And Yamashita’s the same: even if it’s a particularly complex shot or some very detailed acting, it’s always so simple. You can tell he’s thinking about everything, but he also puts exaggeration whenever necessary.

For instance, there are the episodes Kogawa was animation director for on Xabungle…

Yes, there’s episode 1 and a few others… There’s one around the end?

Takeshi Honda: Right, right! There’s that episode where a new female character appears and dies immediately, right? The animation is really cartoony all the time. It’s impressive how he manages to create such a rich movement with so few drawings. Back then, I’m not sure if I should say that I was a fan, but I followed Kogawa’s work already – it was so fun.

Did you use any manuals aside from Kogawa’s?

Takeshi Honda: Hmm, I guess I owned some others? But the one I’d recommend to aspiring animators is definitely Kogawa’s.

Regarding that way of approaching animation – not just accuracy but also exaggeration – what’s your own take? You’ve used rotoscoping quite a bit, after all.

Takeshi Honda: That’s true. The thing with rotoscoping is that you can be very accurate with minimal effort. In that sense, it’s possible to create something richer than just the movement you imagine by yourself, and it’s more accessible than just figuring out how it’ll go in your head. But the thing is, if you only do that, it ends up taking quite some time.

So, I’ve changed my way of doing things: I take some reference videos, which I watch frame-by-frame, and just use a few frames while I’m drawing.

Which is to say, you don’t trace over the whole thing, but just a few poses?

Takeshi Honda: Yes, that’s it. I just copy a few of the reference footage’s frames, and the result often ends up pretty good.

How about Hiroyuki Okiura? Looking at his animation, it looks like he’s trying to avoid any possible inaccuracies.

Takeshi Honda: No, Okiura doesn’t just copy real anatomy! It’s true that he’s trying to match reality as closely as possible, but it’s impossible to create interesting animation if you just do that. In that sense, I think he was influenced by Ohira – especially for the scene of Kusanagi’s dolls in Innocence. Nobody could understand how to make such a disjointed movement, so Okiura looked at Ohira’s drawings over and over, and in the end, the scene turned out to look a bit like Ohira’s style, the way everything isn’t where you expect it to be. That’s when I started to think he had been influenced.

“Miyazaki really had to work to get where he’s at”

That’s unexpected! Going back to the earlier conversation, which one would you say you like the best: Kogawa or Yoshikazu Yasuhiko[13]?

Takeshi Honda: Kogawa or Yasuhiko, huh… The thing with Yasuhiko is that he’s just going on with his talent. It’s actually kinda scary. That’s what a genius looks like.

Wouldn’t you say he’s a bit similar to Miyazaki in that sense?

Takeshi Honda: Not really, actually. Miyazaki’s really a hard worker. Yasuhiko is very learned, too, but Miyazaki really had to work to get where he’s at. When he was younger, he spent a lot of time unable to do anything… He put a lot of effort into Cagliostro, but it apparently didn’t work that well, and after that, he had to wait a few years before he could work on a feature again, and he spent quite a lot of time working for others again. There was the TV Lupin, then Holmes, and finally Nausicaä. That was his chance, and he climbed up from there to where he is today.

Yasuhiko’s pretty different. He was always a genius, and from the very beginning, his works were fitting for one. Even though the stories could be a bit weak…

Ah, I see what you mean.

Takeshi Honda: Right? His manga are really good, but… He was from Mushi Pro, right? So he took a lot of influence from Osamu Tezuka. Even though the stories can be serious, in the middle of a very dramatic scene, he’ll insert some gags, even though it’s unnecessary! That’s just like Tezuka. That’s the thing. It’s like, even if the story is pretty dark, he can’t resist. Maybe you could say that’s his only weak point.

But even in their personality or how they work, I think Yasuhiko and Miyazaki are similar. The way they control everything in their movies: they do the direction, the storyboard, the designs, the layout, and the animation…

Takeshi Honda: You know, about that, there’s a story from the time of Future Boy Conan. Miyazaki controlled everything on it, so the style was really his all throughout, and it was pretty amazing. Even Yasuhiko hadn’t seen anything like it. So he decided he’d take on the same challenge: that was Giant Gorg, where he did almost everything by himself. He was director, storyboarder, animation director, and layout artist.

Just like Crusher Joe, right? He did all of the rough key animation…

Takeshi Honda: The thing is, Gorg and Joe didn’t really sell, and that kinda made Yasuhiko unhappy. He worked so hard, only for it to not sell… Alongside Ideon, it aired while I was in high school, and I really looked forward to watching each new episode. But for some reason, it wasn’t that popular. I loved it, though, and I still have the DVD box.

“I love drawing people running”

Finally, we talked about eroticism earlier, but I’d like to ask some more about that. It’s a bit embarrassing, but do you put your own fetishes in your drawings?

Takeshi Honda: I totally do!

(laughs) So, for example, let’s talk about Robot on the Road. It’s pretty pervy…

Takeshi Honda: On that one, rather than the sexy parts, I did the gags.

Really?

Takeshi Honda: Inoue’s the one who drew the sexy scenes.

Toshiyuki Inoue!? (laughs)

Takeshi Honda: He’s into that kind of stuff!

I see. (laughs) Did you use any reference, like gravure idols photos or stuff like that?

Takeshi Honda: I had stopped using things like that by that point. I can’t speak for Okiura, though…

Aside from Robot on the Road, you also did Nishi-Ogikubo for the Japan Animator Expo[14], right? In some interview, you said that what you originally wanted to do was a “running woman.”…

Takeshi Honda: Yes, I love drawing people running, so I kinda wanted to do something just with that. Also, you know, the schedule and budget were pretty tight, so we had to do something kinda cheap.

Is that so?

Takeshi Honda: Well, the final result took some time and money, but it wasn’t the initial plan.

I can’t believe you. You had so many amazing artists, and the animation is impressive. I can’t believe it was cheap!

Takeshi Honda: And still… We wanted to do something like The Tale of Princess Kaguya, where the lines and colors are pretty distinct. But the number of colors would have increased significantly if the characters wore clothes. So we made them naked because that way, we’d have to use less colors. That’s how it ended up that way.

You had Shin’ya Ohira with you this time as well.

Takeshi Honda: Well, since we were going with such a style, we had to have people like Ohira or Shinji Hashimoto[15]! That’s what I thought, but I had to calculate whether we could afford them first. (laughs)

Do you like Twilight of the Cockroaches[16]?

Takeshi Honda: Yes, I’ve seen it. Inoue worked on it, didn’t he?

He did. Was it an homage?

Takeshi Honda: An homage… It’s rather that working on Nishi-Ogikubo reminded me that Twilight of the Cockroaches was a thing.

Going back to the running animation, what do you like so much about it?

Takeshi Honda: I animated the part with the background animation, right? When the main character climbs the wall and the bookshelf, runs in the stairs… I could go all out with that.

The reason you like running so much, isn’t it because of Future Boy Conan?

Takeshi Honda: Conan, huh? The running animation in Conan is great. I watched it back in elementary school, and that’s the first anime that made me think the movement itself could be interesting.

But in The Boy and the Heron, the characters almost never run. They’re always walking.

Takeshi Honda: That’s right. During the entire production, I was waiting for them to start running. I asked Miyazaki about it, and he said he kept it for the finale. But they don’t run a lot in the end. (laughs)

So, we’re running out of time, but I have one last thing I’d like to ask about. We’ve talked about Miyazaki, Kogawa, Yasuhiko… But isn’t another of your significant influences Yoshiyuki Sadamoto[17]?

Takeshi Honda: Rather than influence, it’s more that I’ve been drawing his characters for so long. First Nadia, then Evangelion… and Evangelion ended up lasting so long. So yeah, maybe you could say he influenced me in that sense.

Do you still see each other a lot?

Takeshi Honda: We go get some drinks from time to time. But he’s been working on the Grendizer remake recently, right? Just thinking he could ask me to work on it makes me tremble. Grendizer, can you imagine?

Grendizer, come on! That’s so boring. Only old French people like that stuff! (laughs)

Takeshi Honda: Well, there’s something really good about it: it’s the original pilot Tôei turned into a film, The War of the Flying Saucers. I really love that one.

And it looks great, doesn’t it?

Takeshi Honda: People like Reiko Okuyama[18] are on it and everything… And the story is so wild it makes absolutely no sense! I wish they had gone that way on Grendizer as well…

Raideen was airing at the same time, and it’s so much better, isn’t it?

Takeshi Honda: I owned a chôgokin Raideen figure back when I was a kid. It can transform into a bird, right? I thought that was so cool.

Did you watch a lot of Mecha shows?

Takeshi Honda: Well, I guess all the boys from my generation watched Mecha. It was just there. I watched many of the Sunrise shows, including the Tôei ones, like Gaiking.

Aaah, Gaiking! What about Yoshinori Kanada’s episodes[19]?

Takeshi Honda: I love them. That’s what drawing with your instinct is all about!

Just mentioning Gaiking makes me think about him! (laughs)

Takeshi Honda: Kanada’s amazing, but what’s even more amazing is the animation director on his episodes, Takuo Noda.

Right?

Takeshi Honda: Noda could draw just like Kanada back then. Sometimes, you can’t even tell which episode is by Noda and which is by Kanada. It’s really great.

I completely agree. It looks like we’ve run out of time already. Thank you very much for today. It was great talking with you.

All our thanks go to Mr. Honda for his time and kindness. They also go to Fabien Nab, Studio Ghibli’s Nao Amisaki, and Animeland’s Bruno de la Cruz.

Interview by Matteo Watzky and Ludovic Joyet.

Assistance by Arnaud Bastié.

Transcript by Isuzumi.

Introduction, translation, and notes by Matteo Watzky.

Notes

If you want to learn more about the topic, you might be interested in:

The following are affiliate links

By clicking on the following links and placing an order, fullfrontal.moe earns a small amount on your order, which helps support the website.

This article would not have been possible without the help of our patrons! If you like what you read, please support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Ideon is the Ego’s death – Yoshiyuki Tomino Interview [Niigata International Animation Film Festival 2024]

Yoshiyuki Tomino is, without any doubt, one of the most famous and important directors in anime history. Not just one of the creators of Gundam, he is an incredibly prolific creator whose work impacted both robot anime and science-fiction in general. It was during...

“Film festivals are about meetings and discoveries” – Interview with Tarô Maki, Niigata International Animation Film Festival General Producer

As the representative director of planning company Genco, Tarô Maki has been a major figure in the Japanese animation industry for decades. This is due in no part to his role as a producer on some of anime’s greatest successes, notably in the theaters, with films...

“The Niigata festival aims to include everything, from art to entertainment” – Tadashi Sûdo Interview

During our time at the second edition of the Niigata International Animation Film Festival, we had many encounters and reunions. Among those was Mr. Tadashi Sûdo, whom we were used to seeing at the Annecy Animation Festival. While maybe not well-known to the...

Excellent interview, been waiting for it for a while and it was really insightful, great job guys.

Thank you! A very insightful interview!

Recently this film is showing at the cinema in mainland China, I am wondering if you can allow me to translate this article to Chinese and share it among a cinephile community? If you agree, I would keep all the credits in the translation.

You are free to do so 🙂 As long as there is a link to the original article on the website and that there is no commercial use, you can use the content to make translated versions, there is absolutely no problem with that 🙂