First with the Music Video Fantasy for DyE and then with Truckers Delight for Flairs, Jérémie Périn quickly made a name for himself and climbed to the top of the animation industry without compromising by working on commissioned films or in the shadow of a mentor.

A prodigy and a true auteur, Perin is also an eclectic connoisseur, from the classics of cinema to Jungian studies and videogames, but he’s staying close to the grassroots, and so are his works, clever and popular.

His latest movie, Mars Express, which premiered at the 76th Cannes Film Festival and releases on May 3rd in the USA, is a Science Fiction movie as it hasn’t been seen for years, which atmosphere, esthetic, and drama are on par with the golden age of Japanese SF anime.

Of course, we were eager to talk to him about Japanese animation, as his work exudes anime influence.

This article would not have been possible without the help of our patrons! If you like what you read, please support us on Ko-Fi!

“Here I was for one week working with Yasuo Otsuka!”

I’d like to start by talking about you. Afterward, we’ll move to your series Crisis Jung, which is a work I love, and finally Mars Express. But first, you studied at the Gobelins. Can you tell us who your classmates were?

Jérémie Périn: I’m not going to give everybody’s names, maybe just the people who’ve become well-known today: Thomas Romain and Stanislas Brunet, who worked in Japan, mainly at Satelight at first…. There were also Riad Sattouf, BD creator Chloé Cruchaudet, and Jean-Jacques Denis, one of the co-directors of Princesse Dragon and the Dofus film at Ankama. The people I used to hang out with were Riad, Jean-Jacques, and Matthieu Malot, who created a video games company called Mobigame.

Who was the best at drawing in your class? Were people really good?

Jérémie Périn: I can’t say. Anyways, Thomas was the Valedictorian. If I can boast a bit, I was the one he admired the most. That’s what’s most important!

You guys were the first generation of Gobelins students who really liked anime, weren’t you?

Jérémie Périn: Who were fans of Japanese animation? No, I don’t really think so. I mean, the first Frenchman from the Gobelins to work in Japan was David Encinas, who was a few years above us. He even went to Ghibli! Things went pretty slowly, in my year you still had some anime fans and some US animation fans… Things were still pretty balanced.

And the people like Balak, Bastien Vivès?

Jérémie Périn: They came a few years after.

So you didn’t meet them?

Jérémie Périn: I only met them IRL at the time of Lastman season 1.

Did you attend Yasuo Otsuka’s lectures when he came to France?

Jérémie Périn: Yes, but that was unrelated to the Gobelins. Otsuka came when I was in my first or second year. It was what you’d call a masterclass for a week at the Forum des Images in Paris. It was part of this program called “Nouvelles Images du Japon” [translator’s note: New Images of Japan]. That lasted two years.

I was there for the very first edition, and there was a discussion about holding a masterclass for people who studied or worked in animation. There were actually only pros; I just heard about it through friends and applied. I got in, and here I was for one week working with Yasuo Otsuka!

How was it? Do you have any fun memories?

Jérémie Périn: There was this very funny thing which nobody could really expect. Otsuka also taught classes in Japan, in studios, and in schools, and the exercises he gave us were more or less the same as the ones he gave in Japan. And what he thought was very funny, he was really crazy about it, was how differently the Japanese and the French interpreted the exercise.

What he told us was that, in Japan, all the animators gave more-or-less the same result: they followed the model sheet, and the animation was similar, regardless of who animated it. But the French were a mess. Everybody had their own way of doing things. We had to animate the main character from Future Boy Conan; some would just make a cartoon out of it; some would put 10 drawings where they had been asked to put 5 – it was just funnier that way. Otsuka wasn’t offended by it or anything. He just thought it was funny: how culture changes things, how things were very neat in Japan and France was just pure chaos.

What kind of exercises did you do? The one with a girl lifting a rock?

Jérémie Périn: I think it was Conan hitting something with a sledgehammer, a stake, or something. I also remember something with a panther having to jump and avoid boxes falling down. We had to do these two at home before the masterclass actually started. Also, something with effects, like animating fire with the lowest amount of drawing possible…

Didn’t you ever want to follow Otsuka back to Japan, like Eddie Mehong and Christophe Ferreira?

Jérémie Périn: The idea did cross my mind, but then I got too lazy to study Japanese. If you want to work there, you have to go through that. And I also believed that a guy coming from France to Japan would have a harder time becoming a director, which was my goal from the start. I thought that there were already tons of people fighting for that over there, speaking Japanese better and knowing more about the industry there than I did. So they’d surely have more chances.

So you think it would be impossible to become a director in Japan?

Jérémie Périn: I think it’s pretty difficult. I know only one such person, and that didn’t really go well: that’s the director of Tekkon Kinkreet, Michael Arias.

Still, he managed to create a masterpiece.

Jérémie Périn: I’m not so sure about that. I watched it a few years ago, and it didn’t really move me. I like the backgrounds, some things here and there, but… I didn’t really get why the generations after mine got so hyped about that film. Everybody was like, ‘Tekkon Kinkreet, Tekkon Kinkreet!’ So I thought I’d watch it, and I was like, uh… yeah… Why? Maybe it’s the first actual film these people have seen.

“Japanese animation’s ability to go around difficulties through unexpected and dynamic ways always fascinated me”

I believe that, at the Gobelins, you followed a class on limited animation and, instead of doing stuff like UPA or Hanna-Barbera, you went for Japanese-style stuff. Can you tell us more about that?

Jérémie Périn: Limited animation has lots of possibilities. As you said, there’s the American style – stuff like Scooby-Doo, and then the Japanese style, which at the time was infamous for being “poorly animated”. But it was an essentially economic problem, and they found a way around it. I found it interesting because, with a reduced amount of drawings, the Japanese could make things very impactful. This ability to go around difficulties through unexpected and dynamic ways always fascinated me.

I wanted to test this – the method and the techniques – so that’s what I tried to emphasize in those exercises. Most students would borrow things from the Shadoks, The Simpsons… Even though The Simpsons aren’t actually that limited. But it’s certainly simpler to draw than Fist of the North Star, which is what I picked. That certainly puzzled the person in charge of that course because when he saw Fist of the North Star’s model sheets, he couldn’t fathom that it was limited. He was kinda old-school, so for him, complicated drawings meant complicated animation and were correlated to the overall budget of a project. Whereas the drawings in Fist of the North Star are complex and very detailed, but the animation isn’t.

It is complicated in a way, but it’s a very specific way: there aren’t a lot of in-betweens, things like that. These are methods meant to compensate for the lack of animation – at some points, it’s more like illustrations. In Fist of the North Star, there’s something romantic, excessive, and so adding lots of small lines really works out.

You also rediscovered an unknown French limited animation masterpiece, Fabienne Dupond, so no one can say you didn’t study French limited animation.

Jérémie Périn: Yeah, we dug it out of the grave. (laughs)

So you have many kinds of limited animation. For you, what’s the fundamental difference between all of these?

Jérémie Périn: As I just said, in Japan, they compensate for the lack of drawings through a more elaborate framework. Taking the old Toei series, which were extremely limited, you had a lot of effort put into the photography, with lighting, parallax effects, all that stuff.

In Western – both American and European – animation, depth-of-field wasn’t really something important. It was much closer to stage theater – you have this very horizontal, flat field and the characters rarely moved into depth. Whereas in Grendizer, the characters run in the hallways and are animated in perspective. In Scooby-Doo, they just run from the profile with the backgrounds looping behind them. You can notice it most of the time, too.

Also, in things like Grendizer, Harlock, or Cobra – which isn’t actually that limited either – you have a money shot or two at some point that creates a strong contrast effect. It’s almost like Sergio Leone, in a sense: it’s very still for a long time, and then all of a sudden, for the climax or whatever, the animation explodes. There, you’ll have something more elaborate, more animated, which, by contrast, seems much stronger and creates emotion. In that regard, Western limited animation is more uniform.

What about layouts?

Jérémie Périn: Well, in Japan, the key animator does the layout. Whereas in the West – including my own works – it’s not always the same person. I’ve already had people do both, but in most cases the layout and animation teams are separate.

French animators have been looking towards Japan for a while, right? Your generation is rather early, but do you have any idea who started it all? The first French guy who wanted to do it the Japanese way?

Jérémie Périn: That’s hard to say. It was progressive, and it wasn’t just the French. For instance, in an interview, Glen Keane said that for the hair animation on The Rescuers Down Under, he took inspiration from Akira – the way they animated the hair on the motorcycle chases. The same goes for Pixar: John Lasseter was never shy about his love for Miyazaki. He had discovered The Castle of Cagliostro a while before anybody. But that’s how the animation world is: everybody watches what the others are doing, we’re all specialists.

Right, but at some point, there was really a desire to copy, wasn’t there? Stuff like Totally Spies on which you worked, Martin Mystère… Though the big eyes perhaps weren’t a big success.

Jérémie Périn: Maybe it started just before, with The Powerpuff Girls. The aesthetic was at a halfpoint between Japanese stuff and 50s US things, UPA and all that. You can see the speedlines when they move and everything: that’s very Japanese. That’s also because, in the US, they got things like Speed Racer – we, in France, got Grendizer. It’s these kinds of visual codes.

Another thing is the effects. In the way they handled the effects of Futurama, you can see the Japanese influence. Before Akira and all that, the effects were very different: just look at the flames and explosions in Disney movies… So, I think Japan has had a big influence on the animation of water, fire, smoke…

Now, everybody wants to do Japanese animation. Not just the style, but also the pipeline, the staging… What’s your opinion?

Jérémie Périn: I don’t really want to copy Japan. It’s meaningless because I think that the French and Japanese pipelines aren’t the same. What I’m trying to do is borrow the achievements from wherever I can, whether that is American or Japanese, live-action or animated… and then integrate them or use them insofar as they can serve my projects. Cinematic language and techniques are just a huge toolbox in which I’ll take stuff because it worked well before. It worked before, but it can also lead you to new ideas, some nobody’s had before.

But, of course, having watched Japanese animation for so long means there’s some obvious influence. But when you show something like Lastman or the things you cited to a Japanese person, they’ll recognize that it’s not Japanese. They see it immediately.

Why? Is it the designs?

Jérémie Périn: That’s part of it. The drawings, the overall aesthetic, the tone… Lastman is too weird to fit into the genres of Japanese animation. Maybe you think it’s a sort of shônen jump style anime, but it’s actually not. Shônen anime is something with very rigid rules, it’s a very specific box. Lastman goes way too adult way too fast even though it started very dumb.

That’s actually one of the things that got us in trouble when the comic came out in Japan. The publishers didn’t really know where to put it in the Japanese market.

“A realistic style is the best way to go if you have any tone changes”

Now I’d like to talk about your style, or rather your styles. I’d say you have two: one that is psychedelic, colored, completely crazy, and heavily inspired by video games with things like Suzy and Truckers Delight. The other, more famous, is darker and more serious, inspired by live-action: that’s Fantasy, Lastman, Crisis Jung, Mars Express… If I could define it in a few words, I would say De Palma without the long takes…

Jérémie Périn: I like it.

Can you say how that “serious” style emerged?

Jérémie Périn: It was with Fantasy – or rather just before that, something rather serious because it was commissioned work. It was the opening film for a Givenchy fashion show, from 2004 I believe. It was the first time I did something realistic, serious, whaddya call it.

You had to copy the animated scene of Kill Bill…

Jérémie Périn: It wasn’t copying, but the stylist loved that kind of thing. He also loved Animatrix, so he wanted something in that style., like a fight in the fashion world. The whole thing was a bit fuzzy, but they had given me the scenario.

So were you rather free?

Jérémie Périn: Not that much, but I had leeway in terms of direction. They didn’t bother me too much with the direction, except for the fights: some of it was cut. I was like, it’s a fight. Obviously, the hero has to take some hits. You have to create suspense, right? But the stylist who commissioned it didn’t want to get hit. That sounded dumb because there’s no twist, no suspense anymore. The hero was just too strong…

Anyways, it’s on Fantasy that I really asked myself why I should use this serious, or let’s say, realistic, style. That MV was all about a switch in the genre and the content halfway, so it was important to find an aesthetic that didn’t betray that. The first half of the MV is about those teenagers discovering their feelings; there’s a bit of eroticism but also innocence and everything… Whereas the second half goes into horror territory. So, if I had gone with a dark aesthetic from the very start, it would have spoiled everything. The beginning would’ve looked cynical, right? Like why would I show such stuff with stark, black shadows and kinda gross characters when it’s actually just two teens playing in a pool… But with a cuter, more cartoony style, the second half wouldn’t have worked. It would have seemed too ironic, you know? Absolute horrors with cute characters, ok, but I didn’t want to do Happy Tree Friends. So, I thought a realistic style was a good midpoint for both atmospheres and made it possible to go from one to the other without too much difficulty.

Did you have Japanese realist-style animation in mind? People like Okiura, Kise?

Jérémie Périn: Of course, I was fascinated by this stuff. I loved the Patlabor films, Mamoru Oshii in general, and also Otomo, Kawajiri… I wanted to experiment with similar stuff. In French animation, such things didn’t really exist. When it happened, it was in such industrial circumstances that you couldn’t really work with realistic drawings with any solidity. It was more like semi-realism relying on ready-made recipes with always the same happy endings. I wanted something more solid.

Watching it again today, I noticed all the weaknesses, but back then, it was necessary to go through there…

You’re still pretty strong on anatomy. Is that the Gobelins’ training?

Jérémie Périn: I don’t think the animation always catches up, though… But that’s the problem, when you do something and watch it again years later, you feel kinda… It’s the same for Lastman. Now, I think lots of things are poorly done.

Have you completely laid aside your psychedelic style now?

Jérémie Périn: At the moment, I think so, yes.

Don’t you want to get back to it?

Jérémie Périn: Maybe. Maybe one day I’ll want to do a comedy. If it makes sense to have a dumber, weirder style. But now, as I just explained for Fantasy, a realistic style is the best way to go if you have any tone changes. It’s practical, to a certain degree, and it’s also more accessible for the audience than something very stylized. I think the stylization comes in very specific moments, some sequences where you go deep into the character’s psychology and try to create specific emotions. That’s something I want to try out in my next film: a bit less rigidity, a bit more fun.

“In films, I get involved pretty much everywhere”

Let’s talk about drawing now. You’ve gone through the Gobelins, so I’d tend to think you’re really good at it, but from what I understand, you actually don’t draw that much. You’re almost more like Takahata than Miyazaki.

Jérémie Périn: I actually haven’t drawn anything since last May.

That’s weird.

Jérémie Périn: I do whatever I want!

Tell me why!

Jérémie Périn: I’m not a guy who draws compulsively. I’m not like Joann Sfar or Cabu, people who need to draw all the time, even when they’re talking to people. I’m not like that. I don’t have sketchbooks that I’d foil every day. I don’t give a damn. I don’t actually like drawing for the sake of it. I’m done with that: I like drawing when it’s to tell a story, talk about a character, or something. I need to have something greater – that I feel is greater. So, a narrative, a cinematic project.

That’s why I’ve always had problems with illustrations. I’ve done some, but I’m not good at it. What I love is creating frames with the knowledge that there’s something before and something after. I’ve lost that thing I had when I was young when I just loved drawing for the sake of it.

So you’re a pure director. That’s a shame because I hope to see you again soon at a signing session…

Jérémie Périn: For signing sessions, I don’t draw. That’s a thing for comic artists. Comic artists and publishers made that a rule: when artists do signing sessions, they have to draw. Why should I have to comply with that?

So, would you say you’re someone who delegates easily?

Jérémie Périn: It depends on the people. I have some partners close to my heart, like Hanne Galvez, Nils Robin, Mikael Robert… There’s no problem with them. There are others, but these are the ones I trust most. We’ve worked together a lot. We’re compatible in lots of ways… But it’s not always like that: even if I trust someone, if there’s something I don’t like in terms of style, I won’t hesitate to correct or even redraw.

But you’re not too involved in the animation of your films?

Jérémie Périn: That’s different. In films, I get involved pretty much everywhere. First things first, I do most of the storyboard myself.

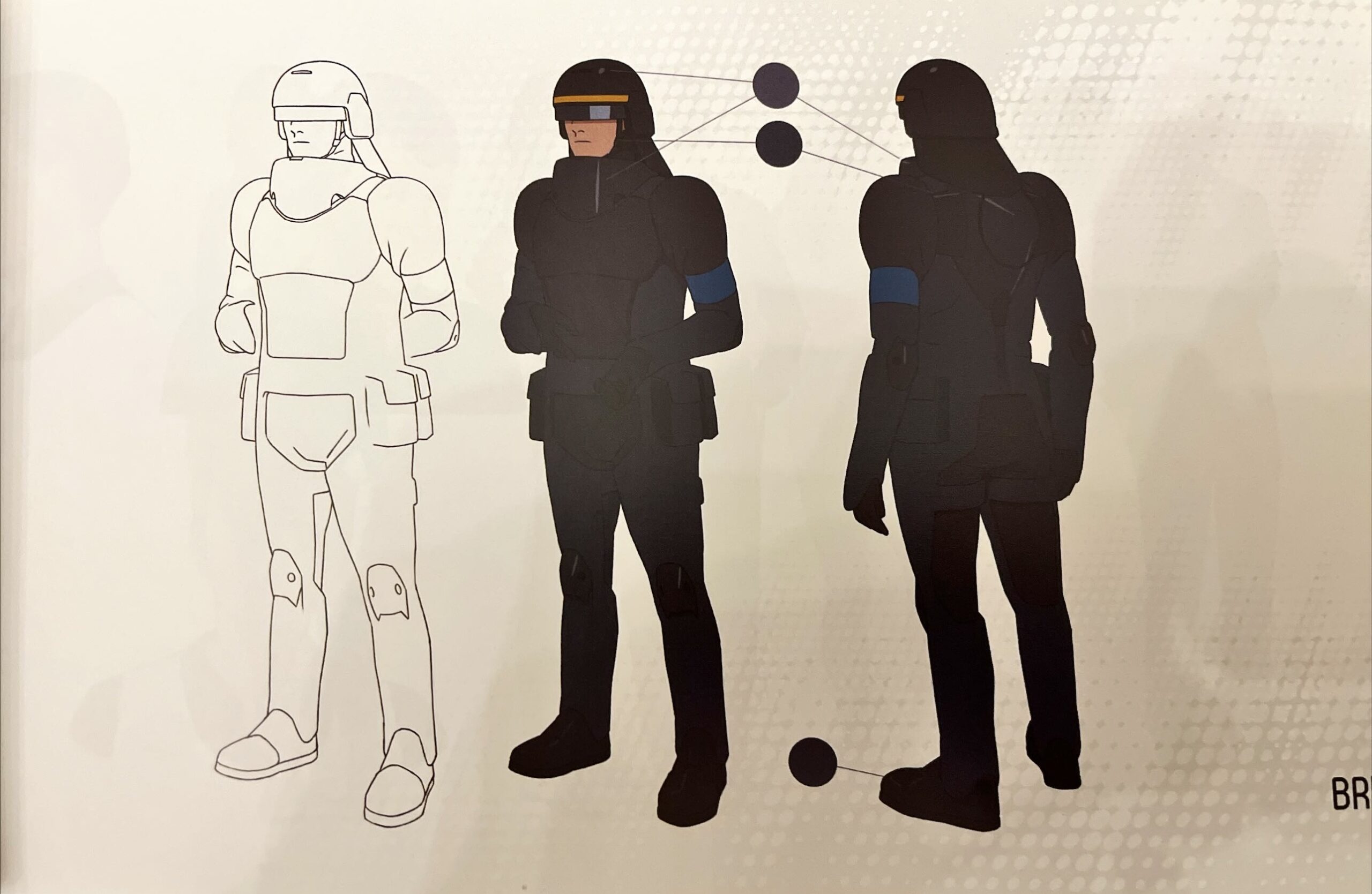

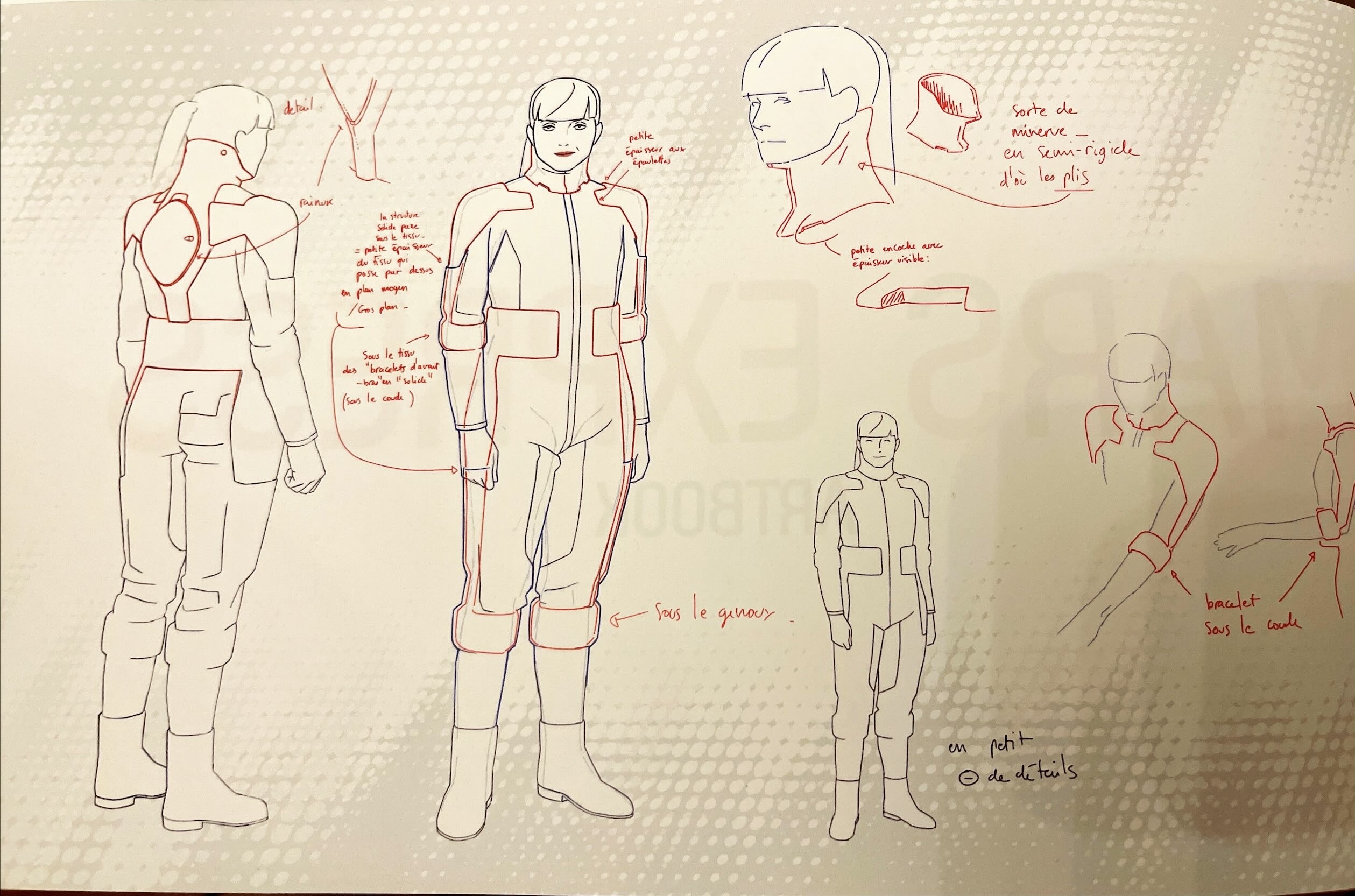

I do a lot of character designs, and I’m very involved in the layouts: I check them, redraw them if necessary… Same for the animation. Or rather, on Mars Express, Nils and Hanne did it very well, but I’d go over them for small details, things that might have been lost over the course of the shots… Also props, I did lots of props, and small objects. On Mars Express, I thought I’d do more animation, but in the end I didn’t get that much time for it. But I did do some shots myself.

Which ones?

Jérémie Périn: Notably some at the beginning, when Aline jumps from one building to another when she chases after Roberta. We used that sequence as a teaser, and I animated a few shots when Aline jumps and manages to climb back up. Also, I did the robot exploding in the machine at the end. Some effects too, a lot of water and foam, for instance on Carlos during the car crash. Basically, they were small things that the others either couldn’t do, didn’t have the time to do, or weren’t there anymore to do.

As you said, that’s not a lot.

Jérémie Périn: I did at most ten shots. Maybe a bit more, but it was small things, like Carlos’ clothes tearing down when the monster Raphaël tears away his clothes in the final fight. But it’s only small things scattered all over, so I can’t say I did it; it’s not my work when I just made some minor changes. The only shots I did completely by myself would be Aline’s jump. When she lands, the high-angle shot, the one with just her hands… And when Roberta falls down in the room and makes a roll.

Did you also do the designs?

Jérémie Périn: For that scene, yes, I designed Roberta in the storyboard.

What about Carole?

Jérémie Périn: I did a first design in the storyboard, which was refined, put on paper by Eléa Gobbé-Mévellec, the director of The Swallows of Kabul. I added some touches afterward, but you could say the two of us did it. I improvised a lot of designs in the storyboard, but it wasn’t really set in stone, they changed from one panel to the other… I hesitated a lot.

So it’s not like in Japan, where they put lots of reference poses in the model sheets. These are really minimal…

Jérémie Périn: These kinds of things were done directly in the layouts.

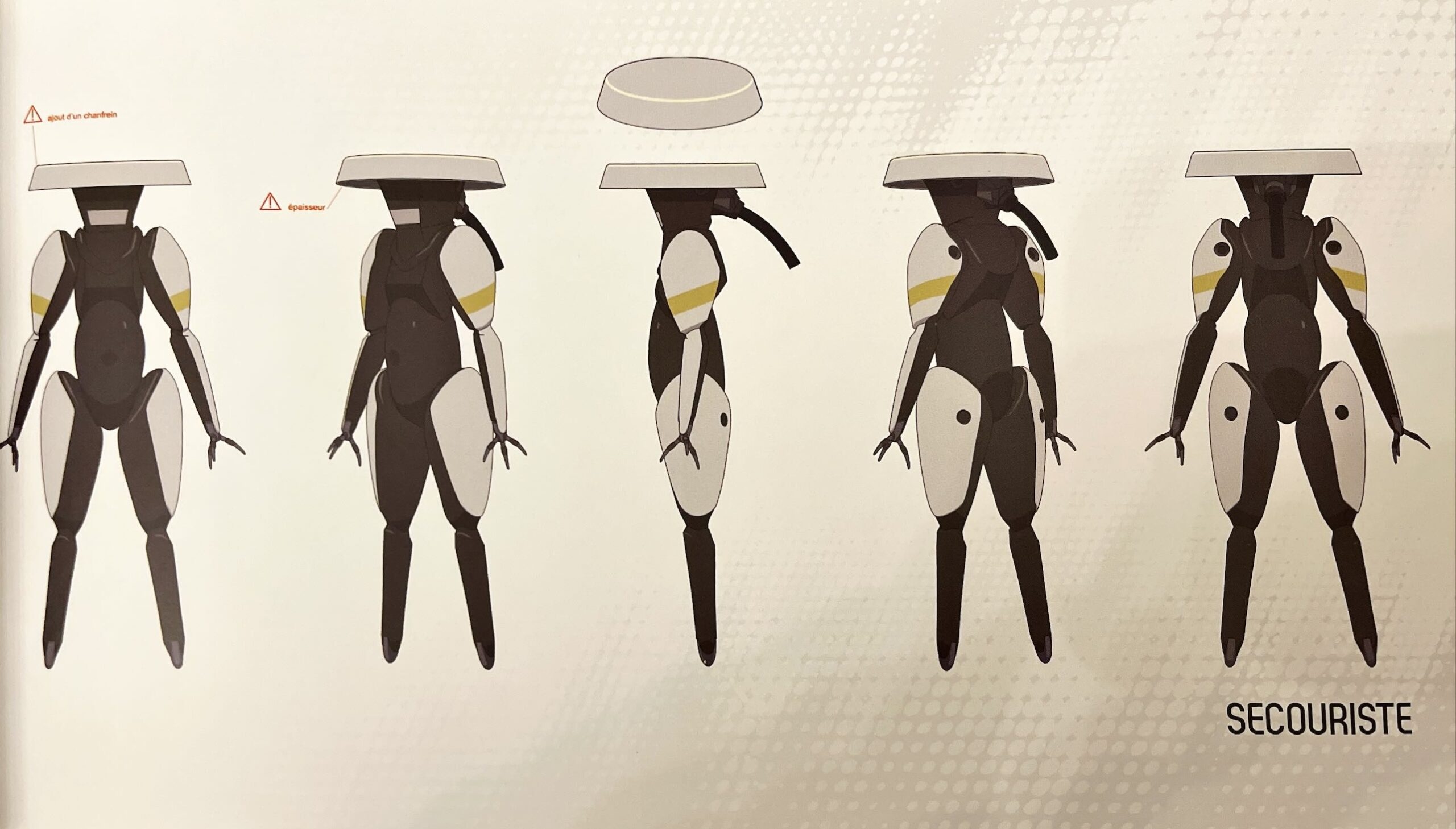

What about the robots?

Jérémie Périn: Some, but not a lot.

Catcher and Coconut Crab are by Baptiste Gaubert…

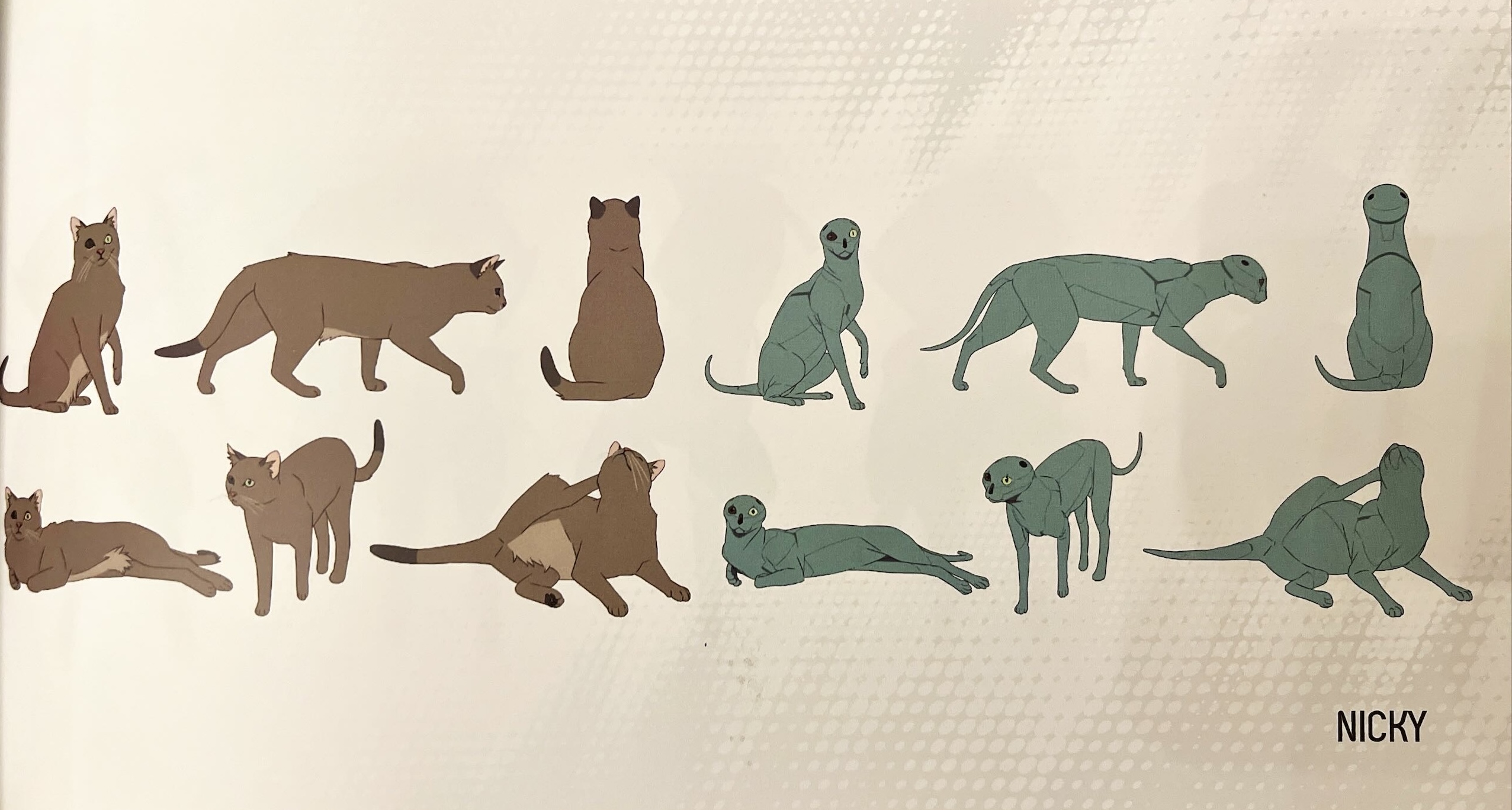

Jérémie Périn: Baptiste did a lot. I did the tank and the cat.

For the first-aid worker, Gobi did the final design, and I did the concept design.

It’s really nice.

Jérémie Périn: Designs were pretty much split between the team. Jonathan Djob Nkondo also made lots of robots.

Oh, he was on Mars Express as well? He worked on Sirocco, too.

Jérémie Périn: I didn’t know that, but that doesn’t surprise me.

“I don’t think you always have to know about everything”

That’s one of the things I wanted to ask about. In Japan, there are so-called “star animators”. What about France? They’re not well-known at all, right?

Jérémie Périn: Right.

But Djob is one of the best animators in France.

Jérémie Périn: Yeah, but you know, you gotta stop for a moment. Japanese star animators aren’t famous either, only fans know about them.

Right, but there are more animation fans in Japan.

Jérémie Périn: That’s true. But we’re still talking about a very small world. I mean, I see what you’re hinting at, but it’s still very small.

Let’s talk about Djob, then.

Jérémie Périn: Well, he didn’t do animation on Mars Express; he just did robot designs.

Apparently, he went to see Benoît Chieux and asked him to work on Sirocco.

Jérémie Périn: That was different for me. I went to ask him, and he said yes.

He mostly did the older generation robots. We had divided the robots between different generations, to be able to make a difference in the technology, the history… Some being older and others more recent. He did the ones who have the most angles. One’s called the Bouloïde [translator’s note: Balloid]. The names aren’t spelled out in the films, but we needed these as reference.

Among us, there was a bit of criticism about the robots. They’re all humanoids, so you can’t really guess the function from the design, they feel like they’re just here for show. So we wondered whether you had thought up backstories or things like that.

Jérémie Périn: Actually, we have always tried to find out reasons for these robots to exist. So, for instance, some take part of their look from mechanical excavators: they’re yellow, there’s one who’s very big with a sort of weird conveyor belt on the arms… You can immediately see it’s a construction site robot, or a factory robot, or something like that.

We did think about that, so it wasn’t done completely at random. Some robots are also thought of as having modules: some have rings on which you could put additional arms… That was Jonathan’s idea. It also gave the impression that there are more robots than there are actually on screen.

But that’s another thing: I don’t think you always have to know about everything. It’s nice to know that a robot actually serves a purpose, but it’s not necessary to always demonstrate it, to show, “Look, we’ve thought about it!” At some point, even in the street, you have cars and all kinds of stuff, they’re just here, you don’t really know why…

Another question we really asked ourselves was: why do the robots have a human form? Does it have any meaning? Can’t it just be only weird shapes? We included some with such shapes, but the majority look like humans or animals. The simple reason for that is that, ultimately, the city is thought for humans, so robots have to go through doors and all that stuff. If the robot is too big or has no hands, it can’t do any of that. Humanoid shapes are necessary to some degree, but it doesn’t necessarily mean robots have to have two arms and all that stuff. It’s just that robots have to adapt to humans and not the other way around. But in other cases, we came up with really flat, thin ones that you could put away more easily, things like that.

What about the cat robot?

Jérémie Périn: That’s just for imitation because maybe there aren’t any real cats anymore in that world. It’s just as dumb as that. And precisely because it’s fake, it’s better than a real cat: if it’s dirty, you can turn it off… It’s about human control over nature, all that stuff.

Another thing about the way you work that I find interesting is that you often work in a duo. Whereas auteurs tend to be solitaries, sister-brother couplings like the Wachowskis or the Coens are rather rare. But you’ve worked a lot with Riad Sattouf for instance.

Jérémie Périn: Yes and no, actually, it never really worked out with Riad.

Is that so?

Jérémie Périn: Yeah. We tried to do an SF series and, to tell you the point we came to, we wanted to do something like Leiji Matsumoto. But he wanted to do Yamato, and I wanted to do Harlock, so that couldn’t work out.

But I never direct in a duo. It’s actually something I can’t understand. I think it only works between brothers and sisters, like the Wachowskis, the Coens, or Farelli. But as soon as you have two separate bodies and souls, one of the personalities takes over – or there’s no personality at all, like in US animated films.

So, Mars Express is not made by the Perin/Sarfati duo? He looks a little invasive…

Jérémie Périn: He’s just the co-writer. In the end, the one who takes the decisions is me and me alone.

“It’s possible for a joke to go too far and to keep some depth at the same time”

Ok, now let’s talk about Crisis Jung. I think it’s a very misunderstood and underestimated work.

Jérémie Périn: Misunderstood, that’s a matter of course.

And, unlike what you’ve said many times, I don’t think it’s just a joke that went too far.

Jérémie Périn: That’s not contradictory. It’s possible for a joke to go too far and to keep some depth at the same time. But at the very beginning, it was just Baptiste and me messing around.

Wasn’t it a sort of catharsis, like you got dumped or something?

Jérémie Périn: He had had his fair share of trouble, and I was coming out of Lastman, so I was completely washed out. So, at first, we wanted to get all of that out, and I’d even go so far as to say that we wanted to do something that would absolutely never sell and extremely problematic – some of the jokes were just too much! And we just laughed at them like two dumbasses.

But at some point, we started getting into it, and we started thinking: ok, it’s absolutely meaningless; it’s just dumb, but what if we put some meaning into that? We’d just have to change this small detail, turn things around a bit… We’d have both sides of the coin: something funny that wasn’t completely meaningless. That’s when studio Bobby Pills came in, and Baptiste wanted to present that dumb thing we had done to them. I said whatever, and they liked it.

But at the very beginning, it was just two guys together, way too late into the night, without any limits, and it just escalated.

Talking about Bobby Pills, the boss poses as a punk, but he’s actually always pretty well-dressed, isn’t he?

Jérémie Périn: That’s right, that’s why I don’t think he’s a real punk. But he’s got a big quality: he trusts people. When people around him believe in something, say they have to try it out, he listens to them and goes for it.

So, for Crisis Jung, once it was done, he told Baptiste that he understood what we wanted to do. He hadn’t at first, but he still went for it. Though we were lucky, because Lastman just ended and lots of people were talking about it. So we could ride on our previous success. I was still riding on it with Mars Express: I could do this film thanks to Lastman.

You did take some holidays, I hope?

Jérémie Périn: Between Crisis Jung and Mars Express? Yes, a bit.

Was the format a big constraint, then?

Jérémie Périn: I think it was good. At least that’s what Mikael Robert, the art director of Lastman, Crisis Jung, and Mars Express, said. I can’t really tell because I wasn’t there for the entire production, and then I left.

Oh? When was that?

Jérémie Périn: I left once the storyboards were over. I initiated the project and wrote a big part of the script, but I was just one of four. After that, I did the very first storyboard to test the rhythm and tone of the series. That became the second episode. The first episode is a bit special: it’s the introduction and everything, so it’s fairly different from the rest. But we needed a model episode, which would work as an example of the plot structure, how the transformation worked, that kind of stuff… I was in charge of all of that, as well as the animation for the transformation. After that, I gave my opinion on some of the other storyboards, but I just followed from afar.

Anyway, what I wanted to say when I mentioned Mikael Robert was the following: he told me it was a pretty hard production, but it only lasted six months. Things were tough, but he knew there’d be an end to it. It wouldn’t be as long as Lastman or Mars Express – Mars Express lasted for 3 years. It was really a long and exhausting run.

Crisis Jung is still pretty long, around one hour?

Jérémie Périn: One hour, yes, it’s a feature.

What about the designs and graphic research?

Jérémie Périn: I did the first sketches to give the overall tone… It doesn’t always work like that. On Mars Express, I did a bunch of character designs, but not all: just the main ones, to give an idea so that the rest of the team could follow up. Even though I tend to come back afterward and change things… But well, if I were to post model sheets on Instagram or whatever – which I should do – I wouldn’t share the characters that multiple people worked on. Or I’d mention them, but I’d rather share my own designs to avoid creating any problems.

Designs for Mars Express’s main character, Aline Ruby

On Crisis Jung, were the design decisions taken by the Bobby Pills people? Since you weren’t too involved…

Jérémie Périn: That’s right. It’s not that I don’t like it. But I had just spent three years on Lastman, drawing big guys fighting all the time; I was kinda tired of it. That’s one of the reasons why Crisis Jung came to be: we wanted to make a parody of that sort of manhood. Anyway, it made me laugh to work on something like that, but I was also tired of it, so I told Jérémie Hoarau and Baptiste Gaubert to do their thing. I didn’t go all the way because I wanted to move on to Mars Express.

Who was the Jungian guy in the group?

Jérémie Périn: The two of us. I went through a Jungian psychoanalysis a few years ago. That’s one of the things that made Baptiste and I get closer: we talked about it, we knew some stuff about it… He was still in the midst of it, and he often talked about how it went. So I suggested the MC see a psychoanalyst for every episode; it was all born that way, as we were talking about things. That’s how it was for the two of us, but it so happened that Laurent Sarfati also did psychoanalysis – I can’t remember if it was Jungian or not, though. I can’t remember about Hoarau.

Everybody’s neurotic in the animation industry, right?

Jérémie Périn: Of course.

“Every element in the film must express the character’s thoughts”

Ok, so let’s psychoanalyze Crisis Jung. Usually, works that borrow from Jung are closer to dream analysis, but Crisis Jung goes deeper, there are no dreams, it’s all about the psychoanalysis sessions.

Jérémie Périn: Yeah. What I’m interested in as a director is to use bodies to show what’s inside the characters. Same with settings. Every element in the film must express the character’s thoughts, or their relationships… And for me, that’s directly connected to Jung, who says that when you dream, you always only dream about yourself. So even when you dream about a friend, the representation, the idea you have of your friend is ultimately an idea of yourself.

The gap between these two lines of thought isn’t that wide, so what I, Baptiste, and the others thought was that the world in Crisis Jung is an inner world. That’s how Jung sees things, but just pushed a bit further.

I think everything’s pretty well thought-out, though.

Jérémie Périn: It’s not a dream, but it follows Jung’s interpretation of dreams.

So Jung is Gaubert, who got his heart broken?

Jérémie Périn: I can’t answer for him. That happened to me too, and I wasn’t as energetic as him back then.

Little Jesus is the shadow?

Jérémie Périn: No. There are anima and animus…

The transformation is Jung’s anima?

Jérémie Périn: Of course, but I think the shadow are more like Jung’s companions.

Like Mary Magdalene?

Jérémie Périn: Of course. But Jesus is the opposite, it’s Maria’s anima and animus. But all of that is within Jung’s mind.

So he was kind of a toxic boyfriend?

Jérémie Périn: Of course he was.

But does he get her back in the end?

Jérémie Périn: Yes, I think he finds peace at the end and that it’s a happy ending.

Does the parodic side come from Bobby?

Jérémie Périn: That came from us. Maybe I was the one who wanted to mess around rather than Gaubert – it made him laugh, but he was pretty serious about it.

Did it make him cry too?

Jérémie Périn: I can’t tell because we wrote all that bullshit remotely. Maybe he went to cry somewhere, but I wasn’t there to see it. Let’s just say I had more distance and irony than him. I mean, he made jokes as well, so it’s not just like I was the funny side and him the serious side.

What about the voice acting? Isn’t it a bit too much?

Jérémie Périn: I wasn’t involved in it.

I thought you were. Since it’s a bit like Fist of the North Star…

Jérémie Périn: Yeah, but I wasn’t involved.

So you didn’t experience the production; you just had fun during the pre-production.

Jérémie Périn: Right.

Let’s talk about Japanese animation again. You went very hard with all the limited animation tricks, especially bank animation.

Jérémie Périn: That was the idea. We knew we wouldn’t have a big budget, so we kept trying out tricks like that. That’s why we used a post-apocalyptic setting; because nothing looks more like one desert than another desert – basically, we could copy-paste.

Also, we thought about making it a show heavily reliant on tropes: something with the same situations in repeat, the same structure with the transformation scene, the poetic scene… Like Metal Hero, tokusatsu series, that kind of stuff.

So your point of reference was tokusatsu dramas rather than magical girls or robot anime series?

Jérémie Périn: All of that at the same time. All these series follow the same format for the same budget reasons. By the way, the Americans do the same thing: look at hospital series like House M.D. . It all happens in the same place because that way, you can save money. The story structures are the same, too… All these narrative techniques are used to save money, to be efficient and dynamic.

Who had this idea of relying on tropes?

Jérémie Périn: I think it was me. I’m fascinated by such shows.

Which shows in particular?

Jérémie Périn: Old classics like Space Sheriff Gavan, Bioman and every Super Sentai… But you can also spot anime like Sailor Moon, or Utena.

“The starting point was that I wanted to make SF”

Ok, let’s move to Mars Express. I believe you wanted to pay tribute to Chris Hülsbeck?

Jérémie Périn: Among other things. There were shots with signs indicating streets, and I thought about how we should name them. Street and building names change pretty regularly, and as time goes by, you start seeing increasingly contemporary people, right? The movie takes place 200 years in the future, so I thought, let’s put video game creators. Nowadays, nobody cares about them; people think it isn’t real culture or whatever, but in 200 years, this will have become a legitimate culture. That’s my way of defending my cause.

Anyways, you made a hit with Lastman, you were given carte blanche and wanted to do hard SF.

Jérémie Périn: Yeah. The starting point was that I wanted to make SF. But there are lots of subgenres in SF… What was missing when we started was hard SF. There were lots of magical stuff, post-apocalyptic, fantasy works, but none of that concrete SF, based on actual scientific and technological knowledge. So we took that bet.

In Japan, it’s almost completely disappeared as well…

Jérémie Périn: I know, but it’s not just Japan. I feel like we’re in a time where it’s hard to project yourself into the future. Because the present itself doesn’t shine a lot, whether it’s animation, live-action, or games, most SF nowadays is post-apocalyptic. Things like The Last of Us or that Japanese one, Heavenly Delusion, are post-apocalyptic and really intriguing. I’m really looking forward to season 2…

All of that stuff is really good, but it’s ultimately the reflection of a very anxious time. People are more worried about collapse than trying to rebuild the future.

The big thing in Japan right now is isekai. You could say even Miyazaki does it now. Doesn’t it seem really regressive?

Jérémie Périn: Actually there’s an isekai I kinda liked recently, Isekai Ojisan. It’s about this Sega fan who goes into a coma and, during that coma, he goes into another world. When he wakes up, he’s totally detached from reality, he doesn’t understand that Sega doesn’t make consoles anymore and the only thing he wants is a Saturn and a Megadrive.

You just convinced me to try it out! (laughs)

Jérémie Périn: I guess that show is sponsored by Sega, because you always see him playing actual games. Like he’s playing Guardian Heroes on his Saturn… With retrogaming, nowadays, you can access incredible stuff.

Anyways, back to SF – it’s a shame, but I think it’s all about timing. Right now, it’s not the time for SF in Japan. And I’d guess that it’s because they’re too afraid to say certain things which might frighten the audience. For instance, when The Silence of the Lambs came out, the producers didn’t want it to be presented as a horror film or advertised in genre film magazines. So they came up with a new word, ‘psychological thriller’. That’s because they were afraid to see their film associated with crappy B-movies. Nowadays, you can speak about horror films, but look at France – The Animal Kingdom, from what I understand, is a fantasy film, but it wasn’t presented at fantasy film festivals. They wanted to distinguish themselves and avoid being associated with pop culture.

Do you go against that kind of stuff?

Jérémie Périn: I say what I want to say and let people do what they want with it.

“In Mars Express, singularity is already there, but in the end, it’s just a metaphor for humans”

As a film about robots and AI, was Mars Express affected in any way by the recent developments brought by ChatGPT or Midjourney? Either positively or negatively?

Jérémie Périn: Neither positively nor negatively, but by the simple fact that people ask me this question. For instance, lots of people ask me whether we used AI in the film or what I think about the whole thing. The truth is all this stuff appeared too late for us to even consider using it or not. The production was nearly over, we didn’t have the time to just start everything again and ask ourselves about it.

Now, as for what I think, it’s not simple, or at least I’m not set on anything. I believe that it’s a tool that can be used ethically for things that don’t involve theft or that kind of stuff. And also to do things that couldn’t be done before. So, in that sense, I have no problem with it. But as always, it depends on who handles it, who owns it, under which conditions… If it’s just something that’s used to put pressure on artists, to tighten deadlines even more… It’s not like you just have to push a button, and things come out! It mustn’t become a sort of formula for producers because the ones who will be affected are the artistic teams. Producers won’t trust them or might even make films entirely with AI. I can accept AI, but it mustn’t go against things made by humans.

You have a pretty mainstream opinion for a director, then. It’s ok if it’s a tool for artists, but not if it’s one for producers.

Jérémie Périn: Exactly. I like AI because of the chaotic, random side of it. You get images you couldn’t have thought of otherwise; it’s a sort of synthesis of world memory. But it has to be processed by human labor afterward – or at least human selection because, at some point, it’s just going to become a compilation of director’s notes, like that Miyazaki-like Zelda thing. Nobody cares about that except degenerate dumbasses on anime forums.

So, singularity isn’t the theme of Mars Express.

Jérémie Périn: It is, but let’s say that singularity has already occurred a long time ago before the plot begins. So the question is: what do we do about it?

Nowadays, when I get asked about AI, it’s not the same thing anymore. In Mars Express, singularity is already there, but in the end, it’s just a metaphor for humans. Robots are just people who are excluded in general.

At Annecy, you mentioned some world-building ideas you didn’t use. Do you remember it?

Jérémie Périn: Yes, hashtag filmmaking.

Can you tell us more about it? Because now, it’s definitely gonna happen.

Jérémie Périn: Yeah, that’s it. When we were writing Mars Express with Laurent, we were wondering about what future cinema would be like. We arrived at the following idea: in a society entirely centered around service, where you can subscribe to anything, where individualism is pushed to the extreme, we thought about algorithms like Netflix that would offer tailor-made services for you and you only. You can interact with it through keywords, and at the end, you get exactly the film you asked for. It’s a masterpiece, the best film ever made, that you had to see at exactly that point in your life. The idea was that it’d shake things up.

So, you wanted to imagine what the death of the director would be like?

Jérémie Périn: Right. I wanted to shoot at my own side.

And right now, it’s already like a lot of Netflix or Hollywood stuff are made by actual people but don’t look like it. It’s already just formulas and algorithms on repeat, without any point.

Did you have this idea because you’re a video game connoisseur and procedural generation is used in video games since almost their beginning?

Jérémie Périn: Procedural generation is different, because it’s restrained inside a well thought gameplay, designed by humans.

Is your hashtag filmmaking fundamentally different?

Jérémie Périn: Maybe, maybe not… I wouldn’t call it procedural, except if the movie is neverending.

Mars Express is also very reliant on tropes, isn’t it? It’s a genre film, with lots of references… Watching it, I feel like I get most of the worldbuilding already, without any explanations needed.

Jérémie Périn: That was the project from the very start. It wasn’t about explaining things but throwing the viewer into a world they don’t necessarily understand at the very start but have to get to know as the film goes… At the same time, I wanted to have this feeling of familiarity putting people at ease. It was to avoid artificial exposition, where the characters know everything about the world but still explain everything, stating things they’ve known for 40 years already… When I see that, it’s like they’re only talking about it because I’m in the room. It breaks my immersion. Why don’t they look me in the eye while they’re at it?

So we had to develop lots of tricks to create that feeling of an instantaneous trip to another world, while keeping it accessible.

So you’re playing with both archetypes and a sort of collective unconscious.

Jérémie Périn: Yeah, but that’s all classical stuff.

Is that so? Don’t you have to be Jungian to do it that well?

Jérémie Périn: I don’t think so. I think there are lots of directors just standing on top of their forebears. That’s only normal: whatever you do, there’s a continuity, a history of forms, things like that. So, admitting that you don’t come from nowhere is also a form of humility. Not going like, “I’ve never seen anything else; it’s all me, my universe”, that kind of stuff. You have to admit you stand in the middle of a wider current.

That’s what Mamoru Oshii is repeating about so-called rip-offs: every director is a plagiarist…

Jérémie Périn: I agree with him, and Coppola was saying something like this, “you have to steal, but from the best, and if it looks original it just means you didn’t get caught”.

But you must get tired of people comparing Mars Express to other films all the time.

Jérémie Périn: Yeah, I get it, but at some point I’m like, ok, can we move on? I mean, on one hand it’s obvious, on the other what more am I supposed to say?

Let’s talk about the end of the movie… Which demo made you choose the group Still?

Jérémie Périn: Every one of them – I saw them on Youtube -Cyril Lambin showed them to me.

You didn’t search on your own on pouet.net?

Jérémie Périn: No, I’d rather ask a specialist who, moreover, has connections. He’s a good friend of Alex Pilot, who made the movie’s making-of and directed the Temps Réel show on the former Nolife channel. He showed me some playlists of many demo makers, and I liked this group right away: there was quite a versatility in what they did, and I was under the impression that we would go along well.

You’re not going to Demo parties?

Jérémie Périn: No, never been to.

What are the technical characteristics of the movie’s demo? Did you impose a memory size limit?

Jérémie Périn: I don’t know. I didn’t because it would end up in a video. But at first, I must admit I intended the scene to have a frame rate higher than the rest of the movie. Ultimately, we weren’t able to do so because of money issues.

Was it because it wasn’t technically usable in the movie theaters?

Jérémie Périn: No, I think it is possible to do so using a multiple of 24Hz. It’s actually something that I want to work on for my next movie.

“I wanted to do it all alone to shake things up”

Regarding the storyboard, I believe you wanted to do it all yourself, which is pretty rare in France.

Jérémie Périn: That’s true. I wanted to do it all alone to shake things up in a way, but also to be sure I could control things.

But, given how the production went, you couldn’t do it all alone in the end?

Jérémie Périn: At some point, the producer found it too long and started saying that if we didn’t start things immediately, we’d lose such and such sources of funding or whatever. So, there was some pressure, and we had to speed up the storyboarding. I chose some people to help me, mostly the main animators of the film because they’d think up shots in terms of how difficult they might be to animate and maybe change things since they’d be the ones to animate them in the end.

How much of the film have you storyboarded?

Jérémie Périn: I don’t know, but maybe two-thirds, maybe three-quarters? And, of course, I didn’t let the others do their thing on their own; we planned things out, talked a lot… It’s not like all of a sudden, a part of the film wasn’t mine anymore. I also corrected lots of things. I redrew the entire storyboard for the ending, or I’d change things during the layout stage.

The storyboard was written in the same order as the plot?

Jérémie Périn: Yes. In the US, they tend to write a script first, then start the storyboard, then realize it doesn’t work and throw away entire scenes, even when the animation is over already – oh, how I hate that! That’s such a waste of energy and money – but it’s never just money, it’s such a shame for the teams who might lose morale when their work gets treated like that…

In Japan and France, we have less money, so we lock every step. Since the script is done, why should we do the storyboard in disorder? There’s one exception, though: I started with the hotel scene on Earth and skipped the opening scene with the cat in the bedroom. That’s because we quickly realized we needed something to show at the Cartoon Movie – at least a 40-second teaser and maybe some additional storyboard to add context. We thought that the opening scene wasn’t very interesting on its own, that we needed the protagonists and everything. So I started with the entire sequence on Earth until the airport, then I did the opening and went back where I stopped.

In the making-of, we can see both the storyboard and the animatic. Were there any differences between the two?

Jérémie Périn: Not really. Storyboards in France have become weird. You don’t do it on sheets or whatever – with stuff like ToonBoom or Storyboard Pro, you can play it over, and so you already have time, timing, and some movement. It’s already close to an animatic. So you could say they’re almost the same, except that the editing in the animatic is more final. Because when you don’t have the recording of the voices, you kinda time the shots at random. Then the editor, Lika Desiles, took that over: she didn’t change the position of shots or whatever, but she made some shots tighter, and others more spread out. You could call that edited version the animatic.

So the animatic is almost the layouts. Do animators just have to transfer?

Jérémie Périn: Yes, but apparently some people can’t even do that… I was surprised to see the layout’s renderings conflicting with my storyboard. But I don’t want to be mean and talk about it.

In Japan, storyboards are usually rougher and more open to interpretation. In France, does that mean that animators have no freedom at all? They’re not even doing the layouts…

Jérémie Périn: No, because the layout is often just the storyboard, but on model. It doesn’t restrain the animator. What could look like a keyframe is not really one, and animators need to reclaim their scene. Layouts mainly help them to be on model. This is a big issue: Should animators use their own layouts, like in Japan? The problem is that many animators are really skilled in pure animation but not so much in adapting their drawing style to their current work. External layouts are a required support for them. It would be a shame to do without them just because they can’t adapt their drawing to the movie’s designs.

Moving on to the animation, it’s always very, very consistent. I suppose that has something to do with the two chief animators, Nils Robin and Hanne Galvez.

Jérémie Périn: Well, about that, we really did it like in Japan, except we didn’t have different kinds of papers to indicate whether it’s the chief animator or the director who did retakes. But we did have animation directors – in fact, we had three because Hanne had to leave, and Nicolas Capitaine took on her role.

I first talked with the chief animators about each scene, sometimes with the key animators as well. At every stage, there were back-and-forths between the key animator and the chief animator, and at the end, it was submitted to me. If, during the process, there were any questions they couldn’t solve, they also came to see me. I’d explain or do some drawings. It worked rather well, and, in the end, I asked them to send me full scenes rather than single shots. It’s better to keep the continuity of each sequence; if not, you can’t realize when there’s a jump cut or when a detail has disappeared or something.

In the end, when there was a huge mistake, I’d either send it back for retakes or correct it myself. I did things myself in lots of instances just because there was so much pressure for everything.

Is that way of doing things standard in France?

Jérémie Périn: It is, I think.

So, there wasn’t anything explicitly “Japanese” in your way of doing things?

Jérémie Périn: I don’t think so.

What would have been very Japanese would have been for the key animators to do their own layouts, but animators in France aren’t trained to do it. The issue is that some people will be great at doing animation but less good at drawing, or at least at drawing things they’re not used to. So, they need someone else to do the layout. And anyway, it would be a shame to pass on their great animation just because they can’t draw on-model layouts. Also, Japanese layouts include both characters and backgrounds. But whereas most animators might be very good at characters, they’re less good at backgrounds, and we couldn’t force that on them. Making that the norm meant cutting ourselves off from a lot of talented people. Realism is becoming increasingly standard in French animation, but it’s far from mainstream anymore.

I saw beautiful explosions, are they from Olivier Malric?

Jérémie Périn: Yes, with Fred Macé and Stéphane Martzolf, they did most of the film’s effects. But I can’t name all the great animators from the movie, so I will stop there.

“We went for cel-shading very quickly”

Talking about backgrounds, let’s talk about the art director Mikael Robert. You’ve been working together for a while.

Jérémie Périn: He was originally a friend of Riad Sattouf, so it’s through him that we met back at the Gobelins. He wanted to work in video games. We worked together for an Oggy and the Cockroaches game for Gameboy Advance that never came out. He kept working on games after that, whereas I went back to animation, and we kept bumping into each other. You know, you have these times where you do nothing but the other’s busy, so you keep inviting each other.

I notably managed to get him into animation without him feeling bad about it. Since he had never studied or worked into animation, he was afraid about all kinds of stuff, even completely irrational things. I brought him on Trucker’s Delight, which precisely has a sort of video game aesthetic. In the various studios I went to, people saw his drawings, they saw that it wasn’t just a video game style but more like painting or whatever.

So when Lastman came, it seemed natural to make him the art director, and we’ve kept going since. When you have people you go along well with, it’d be a shame to stop working with them. The further you go together, the more of a telepath you become – you don’t need to explain anymore, you have more references in common, things go faster.

How much involvement did he have in Mars Express’ worldbuilding?

Jérémie Périn: A lot, more than initially planned. At first, I was in charge of all the model sheets, but I wanted him to do half of it with me. Stuff on cars, the overall design of the town, the backgrounds, the furniture… All of that is part of the overall atmosphere of the film.

By the way, the backgrounds and characters work very well together. How did the compositing go?

Jérémie Périn: The images were sometimes too heavy, and the computers didn’t follow – on some shots, they just crashed. In some shots, you have tons of robots on different layers. They’re all in cel-shaded 3D, so you have so many layers, and all of that is bitmap, so pretty heavy… Our computers at the studio were normal ones, not war machines, so we sometimes ran into trouble.

For the 3DCG, did you choose cel-shading from the very start? Or did you try anything els,e too?

Jérémie Périn: We went for cel-shading very quickly, though we tried different kinds, such as shadows that could be calculated. But it felt too realistic, way more than on the 2D characters – the shadows were too animated, too perfect. So we chose to go for simpler shadows, tricks – all the shadows are just textures. So 2D. And then in some scenes the shadows are animated in 2D.

“I wouldn’t say we went over budget, but rather that we had the budget we were supposed to get”

There were a lot of studios working on Mars Express, right?

Jérémie Périn: Around 5, I believe.

Isn’t that a bit like in Japan? But in Japan, they do it to save money, whereas in France, it’s about subsidies…

Jérémie Périn: Yeah, in France, it’s not to save money but to raise the budget, which amounts to pretty much the same. We’re using a system called regional subsidies: administrative regions have a certain amount of grant money to spend, so if you manage to convince them to work on your film, they’ll put out a certain amount of money for it. That’s how French cinema works, both animation and live-action.

For live-action, you have to give back to those areas – so for instance, you’re going to shoot your film there. Whereas for animation, you have to make your film in the areas that have some activities related to animation: Angoulême, the Hauts-de-France, the Réunion, Strasbourg… That’s the ones we worked with, but we didn’t get subsidies from Luxembourg and Ile-de-France, which is where most of the production took place. But most French films fight for the grant from those places, so…

Going back to 3D, was it both a conceptual and practical choice?

Jérémie Périn: Both.

Didn’t that raise the costs in the end?

Jérémie Périn: I don’t really think it did.

But on the practical side, the good thing was that we could design robots without having to ask ourselves whether they’d be hard to draw or not – have some with very geometrical designs, with very complicated fingers and everything. In Japan, they’ve done Gundam all of their life, so they can draw robot hands, but in France, we don’t really do that, and the animators would have gone mad if they had to draw it. In that sense, it’s the opposite of 2D: the longest is to create the assets and the rigging, and once you have that, actually animating shots is very fast.

The interaction between 2D and 3D was pretty complicated. We did some tests on Blender, which was quite laborious, so we gave it up at some point and went for more traditional techniques. We spent some time doing R&D, which was quite interesting.

My biggest regret is that I was met with lots of resistances about having a 3D expert there at studio Je Suis Bien Content, who could have centralized the job of each studio. There were some communication mismatches between us and all the other studios. When we received 3D materials, we couldn’t correct them simply because we didn’t know how. Nobody could do it, so at some point we hired someone part-time. But if we had had someone full-time from the start, we wouldn’t have had to do that.

Were there multiple studios for the 3D?

Jérémie Périn: It was mainly Gao Shan for the characters and vehicles, but the background studio did both 2D and 3D.

Where is it?

Jérémie Périn: At La Réunion.

So, now, if you had to look back on the film, is there something you’d like to change in terms of production? Why did it go over budget – I mean, it happens all the time, but there’s always a reason, right?

Jérémie Périn: I wouldn’t say we went over budget, but rather that we had the budget we were supposed to get. It wasn’t always well spent, first because we tried to save on everything at the start, and then used some production methods that didn’t actually fit the film. Basically we tried to adopt methods that fit the habits of each studio we were working with, but that wouldn’t have fit what Mars Express was going for technically.

Such as 3D?

Jérémie Périn: Such as 3D, but also all the difficulties that go with the realist design style we went for. The same applies to the backgrounds – the amount of money and time required is often underestimated. Since we don’t do a lot of SF in France – at least not enough to learn from each experience, we didn’t really think through all the interfaces, computers, logos… The initial reflex was often to go for flat screens like those from today, but that would feel old. Actually, you have to rethink everything down to the keyboards. So the preproduction was way too short, and we were actually only two people on it.

So now, that’s something I’m trying to do with my producer: I’m trying to teach him some of the basics of compositing and animation so that, when something’s late, he can actually understand why. There’s always a communication issue between artists, technicians, and producers: nobody speaks the same language. So it’s always a pain to explain why one method is better than another; what’s the problem with a background or a compositing mistake… If you just show a jpeg to the producer, it doesn’t go anywhere.

Not all directors know about the technical stuff, either. That must be problematic.

Jérémie Périn: You can be sure that if the director doesn’t come from animation, they won’t know about the technical stuff, and they’ll be annoying. If you have that technical experience, you can convince your team – at least, you can earn their trust because you can judge the work they do, you know how difficult it is, you have this sort of empathy for them. Though I was annoying, I don’t want to act like I wasn’t.

Can you talk about what you’ve got coming next?

Jérémie Périn: I don’t have much to say.

Are you still working with the same producer?

Jérémie Périn: I am. The script’s not written yet, so it’s hard to say anything.

Is it trashy?

Jérémie Périn: It is. Genre stuff, for teens or adults. But nothing’s written yet, I haven’t even created a file for it…

We wish to thank Jérémie Périn for accepting this interview, for his time, and for his friendliness.

Interview by Ludovic Joyet and Lilo Chiche

Transcription by Emilia Hoarfrost

Translation by Matteo Watzky

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Animation is chicken – Chicken for Linda! interview with Chiara Malta and Sébastien Laudenbach

“We looked for a place where animation and live action could have a dialogue” Chicken for Linda! is one of the biggest works in French and, one could say, world animation of both 2023 and 2024. Not only did it reap prizes in nearly every festival it was screened...

“A place where only the drawings exist” – Interview with Benoît Chieux

When we first met with Benoît Chieux at the Forum des Images and saw his feature Sirocco and the Kingdom of the Winds, we were extremely eager to hear more. Indeed, not only is Sirocco an impressive animated movie that combines many influences from all over the...

Do anime events have room for creators? – Interview with Koji Takeuchi

The Annecy International Animation Film Festival is a place of many little pleasures, and one of them is to meet with Kouji Takeuchi, a pillar of the anime industry, and learn a little bit more of Studio Telecom's lore, which you can read more about in our previous...

Recent Comments