Mamoru Hosoda has truly become “the new Miyazaki.” By that, I do not mean that he is or has become Hayao Miyazaki’s heir or that his work follows up on that of the studio Ghibli director. Rather, I mean that Hosoda has taken Miyazaki’s place in Western film discourse: that of the prestigious “anime auteur” that even non-animation fans acknowledge for his talent and place within contemporary cinema. The major difference between the two directors is that Hosoda is aware of this and seems to play with it. Recent remarks about an unnamed Japanese director (which many took to be Hayao Miyazaki) and his representation of female characters are representative of Hosoda’s new place in animation discourse. With the oft-mentioned standing ovation it received at the Cannes film festival, Belle seems to be the very image of Hosoda’s status. The very fact that the film was shown in Cannes, and not at the Annecy International Film festival, is a telling move.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

More than just that, though, Belle is the movie through which Hosoda wants to establish his position within the Japanese scene and world animation. The presence of artists such as Disney designer Jin Kim (Frozen) and Cartoon Saloon director and designer Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart (Wolfwalkers) speaks volumes about the international dimension of the production. As a predominantly musical movie, it deliberately references studio Disney and cites one of the most famous sequences from the Burbank studio’s Beauty and the Beast. While the film certainly strengthens Hosoda’s auteur status by coming back on familiar themes (family, virtual reality, life in the Japanese countryside) and reemploying the same design sense as in previous features, it is far from just repetition. As the director is taking on the world stage, this feature is more collective and international than usual and is, as a result, one of the most ambitious theatrical works to come out of Japan in the last few years.

However, the question is whether Hosoda the artist and Hosoda the world-famous auteur really make a good duo. Or, in other words, whether a movie that does its utmost to be as spectacular as possible can work as a movie.

Spectacle endangering structure

Belle tells the story of 17-year-old Suzu, a shy teenager who lives a parallel life as popular singer Belle in the virtual social media world of U. There, she meets a mysterious user named Dragon and tries to create a friendship with him all the while handling multiple relationship problems in the “real” world. As this short synopsis illustrates, Belle revolves around the duality between U and the “real” world, emphasized aesthetically by U being entirely animated in 3DCG. Lavishly designed, U seems to be intended as the highlight of the movie. It certainly is, in the sense that it often is a dazzling spectacle of virtual architecture supported by breathtaking digital effects. Belle is undoubtedly a success and Hosoda’s most outstanding work yet in its seemingly endless ability to create new worlds and conjure new designs.

The problem is that U seems to have no other purpose than being its own spectacle. The events taking place in it are only loosely connected to the “real-world” narrative until the climax and have, therefore, little emotional impact. This part of the movie is further endangered by what is also one of its strengths: the musical performances. They take such an important place that many sequences within U entirely depend on them – which may very well alienate the viewers that are not immediately taken in by Belle’s songs. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, what Hosoda says about virtual reality and the Internet lacks power or originality. It certainly provides some fun and relatable moments but doesn’t have the impact of his two earlier movies Digimon Adventure: Bokura no War Game and Summer Wars.

On the other hand, Belle works remarkably well as a teen drama on grief, depression, and abuse. Hosoda himself seems to have realized it, as the real climax of the movie takes place outside of U and is much more effective that way. There, Hosoda’s direction comes back to its fundamentals (notably excellent shot compositions and layouts), all working in perfect synergy with strong background art, exemplary photography, and superbly expressive animation. The two “worlds” of the movie are impossible to compare because they are so different, but the “real” one is still much more interesting because its elements are there in service of an actual narrative. Perhaps it is precisely there that U becomes Belle’s weakness: if the “real” world is the emotional drive of the movie, there is no reason for many of its characters to receive so little actual development.

Belle and animation beyond Japan

Aside from these remarks on structure, Belle warrants a few more on context: if, as I have said earlier, it is Hosoda’s definitive entry on the world stage, it needs to be analyzed from that point of view. And it does exemplify a few recent trends.

In the last few years, the market of animated features in Japan seems to have entered a distinct division between two kinds of productions. On the one hand, we have features with relatively limited means or ambition, targeted at a young, often domestic audience (although many do get distributed outside Japan nowadays). Their genre varies, from teen summer movies (Fireworks) to romances (Josée, the Tiger and the Fish), but the paradoxically most representative work of that category is a franchise movie, the most successful Japanese film of all time, Demon Slayer: Infinity Train – ultimately little more than a series of TV episodes put back-to-back.

On the other hand, we’re witnessing more and more prestigious, creatively ambitious works more-or-less explicitly aimed at the general foreign audience, which often premiere in prominent film festivals. Interestingly, these are often associated with directors or studios, as if filling the gap left by Ghibli in the Western perception of Japanese animation: the most prominent among them are Masaaki Yuasa’s Science Saru (Inu-Oh), Makoto Shinkai’s CoMix Wave (Your Name, Weathering with You), Hideaki Anno’s Studio Khara (Evangelion 3.0+1.0: Thrice Upon a Time) and studio 4°C (The Children of the Sea). Of course, Hosoda and his own studio Chizu are major contenders in this competition between Japanese artists.

However, with Belle, Hosoda has just demonstrated he is perhaps the most “international” of all prominent Japanese directors. This isn’t just because he collaborated with non-Japanese artists, even if they are among the most prestigious: after all, this is becoming increasingly mainstream in the Japanese industry. It is rather because Belle perfectly fits into the current animation landscape in terms of techniques and themes.

Japanese animation has always had a notoriously difficult relationship with 3DCG, either failing to master it on the most basic, technical level or to integrate it into a wholly consistent aesthetic approach. But just when 2D animation is making its return on the Western stage, Belle is perhaps one of the best showcases of 3DCG animation to come out of Japan. The CG work is still very uneven, alternating between impressive moments of acting and surprisingly awkward textures. But, for once, its use is aesthetically and narratively justified making it very much a part of the “spectacular” dimension of the movie.

Narratively as well, Belle feels very much of its time. Teenage girls have been regular protagonists in Hosoda’s movies, but they have also become noticeable in many non-Japanese animated films. Frozen was undoubtedly a turning point for Disney, at least in terms of reception; looking towards Europe, we also find the French Calamity and the Irish Wolfwalkers, two distinctly feminist movies featuring charismatic heroines. Following Hosoda’s two previous works, which both focused on young boys, Belle is a return to form for the director and a way for him to follow and further contemporary trends.

Belle is, without any doubt, one of the most important animated features to come out in the last few years, not just in the Japanese scene but in the entirety of world animation. Its visual ambition and creativity are almost unparalleled in many aspects. Paradoxically, however, all these remarkable visual ideas may work in the film’s disservice as a whole. Whether Belle still manages to come out as a fan and audience favorite despite this is very much in the viewers’ hands.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

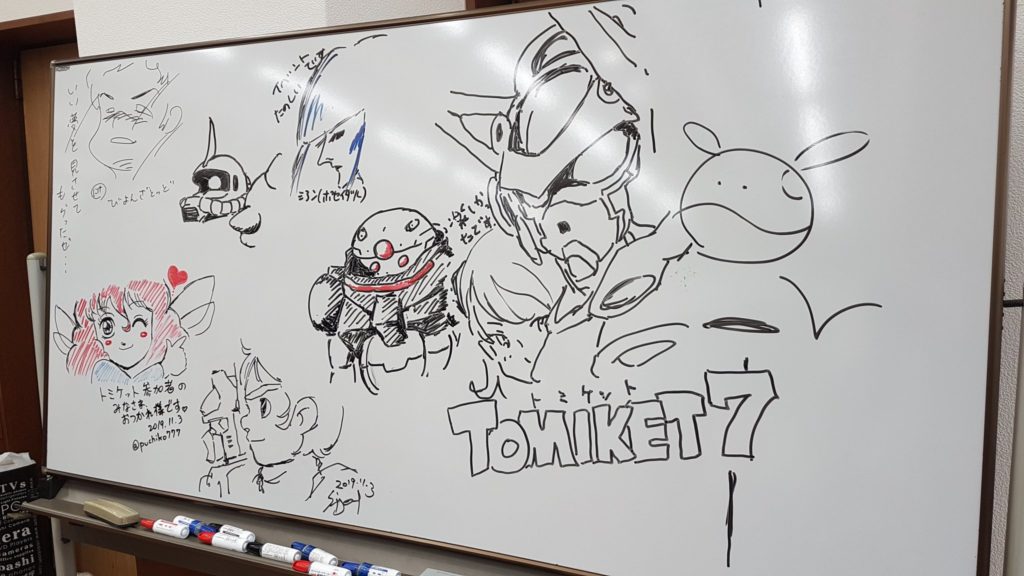

A glimpse at Tomiket

Through my visit to the 7th edition of Tomiket, we would like to dive into what makes the soul of niche Otaku events in Japan. How do Japanese fans express and share their passion for specific interests, and what can you expect out of them?Like our content? Feel...

Gunnm – Yukito Kishiro Panel in Paris

Following his attendance at the Angoulême International Comics Festival, Yukito Kishiro, the manga author behind Gunnm, better known as Battle Angel Alita in English, held a panel in Paris to which a small selection of fans was invited to. The French publisher for...

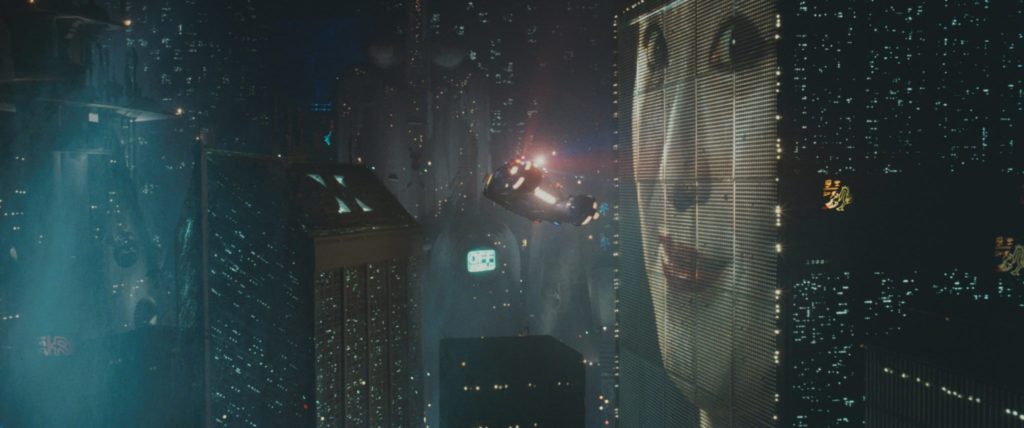

[Cyberpunk://0420] – Cyberpunk Society and Its Future

Cyberpunk —Echo of the past —A bottle to the sea —Drifting along our era's shores —Finding its way before our eyes —Voiceless against a world deafened by its own cry.

Recent Comments