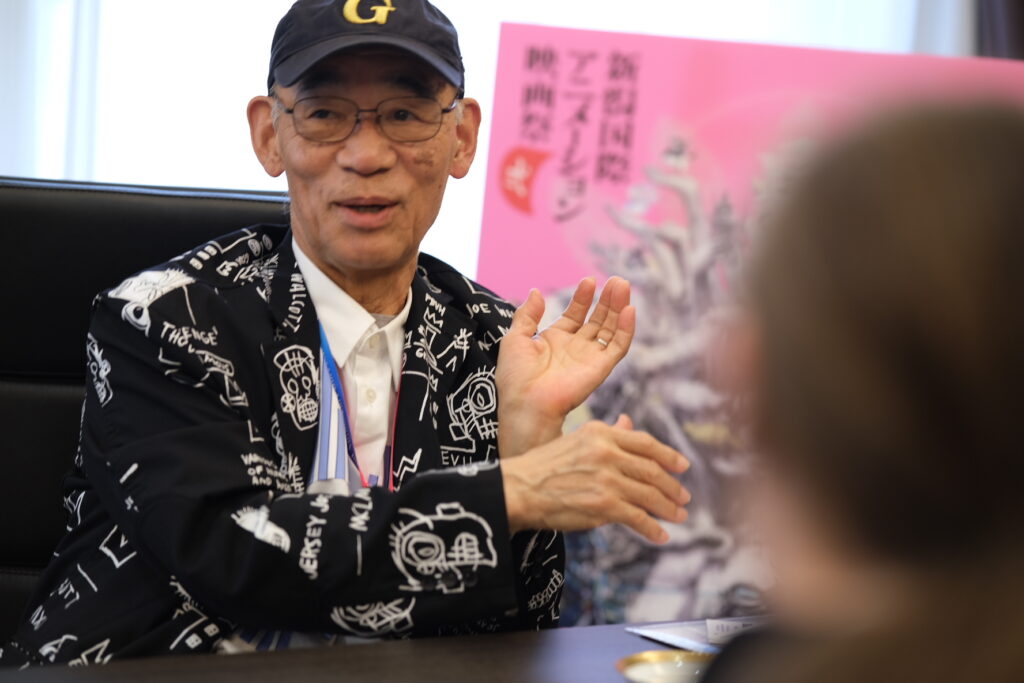

As the director of cult works such as Death Note, Highschool of the Dead, and Attack on Titan seasons 1 to 3, Tetsurô Araki is one of the biggest names in the anime industry. In recent years, he has had many occasions to get his name out, from the movie Bubble to the music video Colors or the openings he directed on series such as SpyXFamily, Vinland Saga, and just recently on The Dangers in My Heart.

Aside from their dramatic style and flamboyant storytelling, what sets Araki’s works aside is their “color” and particularly the director’s focus on photography. Whether that is in atmospheric compositing or in the use of 3DCG, Araki has been a pioneer of many techniques that have now become standard in anime. When we met him in Tokyo in August 2023, we were, therefore, eager to learn more about his creative process as well as his past and future works.

This article would not have been possible without the help of our patrons! If you like what you read, please support us on Ko-Fi!

This interview is available in Japanese. 日本語版はこちらです。

“Beauty emerges out of the way light and shadow are played against each other”

Recently, it seems like you’ve been focusing on opening and music videos. Why is that?

Tetsurô Araki: My next director project is only in the preliminary stages, so we haven’t entered the animation or anything like that yet. But in the meantime, I don’t want to lose contact with the reality of production, so I take on small-scale projects such as MVs or openings. I believe that I should still be able to showcase some short works in the near future.

I’m looking forward to that! In your works so far, there’s always a strong attention to photography. So, what is it that you pay the most attention to during that part of the process?

Tetsurô Araki: That’s right, I always focus a lot on the play of light and shadow. Beauty emerges out of the way they’re played against each other. In order to give light a real existence, shadows are very important, so I’m always cautious about how the shadows are laid out on the screen.

You also use a lot of lens flares.

Tetsurô Araki: You’re right. I love lens flares! It seems that director Shunji Iwai[1] had a huge influence on people of my generation. During all my adolescence, I really got hooked on his work and started wanting to film images as beautiful as his. And Iwai was extremely good at using light in his films; he was also very good at filming women, making them look as beautiful as possible. All visual artists from my generation admire Iwai, and I’ve always longed to do something like his films as well. Every time I see something by someone from my generation, I think, “Ah, they’re also an Iwai fan!”

Aah, I see! Since your career started in Madhouse, I thought it might be Osamu Dezaki[2]’s influence, but… (laughs)

Tetsurô Araki: There might be some of that too. The way Dezaki inserted light in his work and the way he made the sea shine were so beautiful that it would be natural to be influenced by that. I love it. That’s a fact, but I think that Iwai’s influence really is a generational thing – maybe it’s not very well known, but in my case, it’s very strong.

So, I guess it’s the same in Nerawareta Gakuen[3]? There are a lot of lens flares there as well…

Tetsurô Araki: I’ve never directly asked Nakamura[4] about Iwai, but the fact is that, among our group, he was the first to experiment to that degree with such techniques. The episodes he directed on Monster, in particular, are wonderful, and the way he used light in them was impressive. I wasn’t very good back then, so I learned everything from him: I studied how he created lighting effects by looking at every part of his process, from the indication on the layouts and envelopes for the animators to what he said during meetings. I absorbed all of that, and I guess you could say that I really followed his steps.

I’m glad you mentioned all of this because I wanted to talk about your Madhouse days.

Tetsurô Araki: You did? (laughs) I didn’t know there were foreigners who knew so much about me!

I just prepared this a bit. (laughs) I believe that you studied literature at university, so how did you end up in animation?

Tetsurô Araki: If I had entered the industry just after high school, my parents would have been really worried. I believe it’s the same everywhere, so I decided to go to university before I started working. By the time I entered university, I knew I wanted to work in visual arts, but I didn’t know what I’d specialize in yet – animation, live-action, or even theater or manga. I spent my studies thinking about that, and I tried each in turn.

I tried theater out, and I even sent some manuscripts to a publisher, but the thing that worked out best among my friends was the 8-millimeter films we shot together. I started thinking that maybe cinema was a good fit for me. I had failed at all the other things! I wasn’t a very good actor; I couldn’t draw good manga, but I felt comfortable doing films, and the people around me liked what I did. So I decided I’d do films, but then the next question was: live-action or animation? That happened at the time when Neon Genesis Evangelion was incredibly popular, and I wasn’t an exception in that regard: I absolutely loved it, and it led me to choose animation.

And why did you enter Madhouse instead of Gainax or Sunrise?

Tetsurô Araki: I wanted to try Sunrise out, but I applied too late. I started my job applications late because I thought about entering a vocational school. So I lost a few months, and when I finally started, I saw Madhouse’s Master Keaton airing on TV. I really loved it, so I phoned them. They told me to come, and I only got in there because of that timing.

I see. You just mentioned the films you made at university. Do you still have them?

Tetsurô Araki: I still have the tapes somewhere. Actually, I brought them to my job interview at Madhouse, but that didn’t particularly earn me any praise from Mr. Maruyama[5]…

Ah, as a portfolio?

Tetsurô Araki: That’s right. I brought a collection of sketches and the films I had made, but they didn’t say anything about that; instead, they asked if I had a driving license. When I said I did, they told me I could come the next day! Rather than people with artistic abilities, they were looking for people who could drive… Such things aren’t that rare, actually.

“Every artist wants to try to create new images that have never been seen before”

Regarding artistic abilities, it seems like you draw rather well, and that you sometimes do animation on the works you direct. Why is that?

Tetsurô Araki: When I direct an episode, it’s sometimes necessary for me to step up and do animation myself. When what the animator did doesn’t fit what I envisioned, and I can’t find anyone else to do it, I view it as my role as the director to get my hands dirty, and as a result, I’ve progressively gotten better at drawing. Of course, that doesn’t mean I’m anywhere near the level of the industry’s top animators: I’m just around the level of the usual animator in order to fill in for them in case of emergency. In fact, I can’t even draw with a lot of detail; I can’t do anything more than rough key animation, so maybe my level is below that of most animators.

Also, when I’m directing a series, there often is nothing left to do for me on the final episode, whereas all the staff are giving their all, so I help out wherever I can and sometimes draw animation.

With that in mind, would you say you’re particularly strict when it comes to supervising the animation?

Tetsurô Araki: I don’t think I am. In this industry, there are lots of people with unreasonable demands who never use what they’re given or just draw everything themselves. Compared to such types, I tend to use everything animators deliver as much as possible. At least, that’s how I see things.

Coming back to light and photography, a regular collaborator of yours is photography director Kazuhiro Yamada. What would you say is the appeal of his work? Does he have any special techniques?

Tetsurô Araki: Well, Yamada is roughly the same age as me, and we agree on Shunji Iwai! For instance, in the scene where Ageha changes clothes in Swallowtail Butterfly – the lighting in this scene perfectly fits his aesthetics. Neon lights are reflected on the flat surface of buildings, but the rain makes the light flutter… I don’t need to explain Yamada when I want to recreate something like that; he understands it immediately and creates beautiful effects. Working with him is always extremely pleasant because we share the same tastes.

Aside from Mr. Yamada, you’ve also been working a lot with studio Madbox recently. Is that thanks to your connections with Madhouse?

Tetsurô Araki: It happened on SpyXFamily. The director of photography of the show is Ms. Akane Fushihara from Madbox, and I asked her to work on the OP as well. That’s because what she did on the series is absolutely wonderful. Her skill can make the images bright or richly colored, and the way she creates light is fantastic. Before that, on Attack on Titan, I went for a hard and intense approach, but on SpyXFamily and the MV Colors, I started going for a lighter, more colorful atmosphere.

It’s true that, when comparing Attack on Titan and your more recent works, the colors have completely changed.

Tetsurô Araki: I’ve been wanting to try something less heavy. I believe I’d like to test both approaches together in the future. Also, I’m mostly working on things aimed at young people right now, so I’m taking the opportunity to improve my skills in this kind of atmosphere. I’m doing these bright, cheerful things right now, but I guess lots of people are going to fight and die in my works very soon…

You’ve always been using 3DG a lot, but could you explain that? Is it another director’s influence, or did you always want to experiment with new techniques?

Tetsurô Araki: I believe every artist wants to try to create new images that have never been seen before. In my case, the new tool that made that possible was 3DG – it was a new and exciting frontier. It’s just as I was thinking about things like this that I directed Attack on Titan, and I realized that long shots using CG backgrounds with 2D characters would be a perfect fit for the three-dimensional maneuver gear. So, it’s a pure coincidence that my aspirations met something that perfectly fit them. I believe I was really lucky with this.

And now, every time I use CG, I try to go a little further, to experiment with things I haven’t done. It’s what I’m doing right now, and I enjoy it tremendously.

I believe the way you used 3DCG on action scenes in Attack on Titan has been incredibly influential, and now it’s become something standard. What do you think the next stage will be?

Tetsurô Araki: I don’t think it should be thought of as a replacement for hand-drawn animation. What I mean is that if you try to imitate hand-drawn animation, you’ll only end up making people dissatisfied with the result. It’s not really challenging to avoid using CG to do things other than what only CG can do. But I can’t say anything more: I’m also searching for how we can bring things further.

I’m also in the course of testing the range of possibilities. Since the methods are so different, it’s impossible to give an answer before you’ve experienced the real thing.

Storyboards are still mostly hand-drawn, even on CG works, aren’t they? So, in that sense, isn’t part of the method similar, at least from your position as a director?

Tetsurô Araki: I use a 3D software when doing storyboards. For instance, on Bubble, for the parkour scenes, it would have been impossible to do the storyboards without 3D models; otherwise, I couldn’t tell how high the jumps should be and things like that. So, I had a 3D model of the city made, and I drew my storyboard while moving it around on a 3D software. In such a case, 3DCG is an extremely useful tool and has been very helpful in the creation of the storyboard. Before, you had to think up everything in your own head, but now you can try things out, test whether some shots look better than others… It’s really been a blessing.

Do you also do video storyboards or animatics?

Tetsurô Araki: Yes, it’s very important. Makoto Shinkai has had a big influence on the industry, and he’s been using a software called Storyboard Pro, which became somewhat standard around 2017. On my end, I’ve been using it since the first Kabaneri movie, The Battle of Unato. It’s extremely well made in all kinds of aspects, and I guess you could call it the ultimate storyboarding tool. In particular, you can share the video storyboard you drew with the staff very easily, so it’s very important to develop communication among the team.

“Colors is a project I created just so that I could work with Mai Yoneyama”

There were two directors on your MV Colors, you and Yûki Kamiya[6].

Tetsurô Araki: Wow, you know about Kamiya? That’s a surprise! He’s been doing some nice work on Witch from Mercury and Jujustu Kaisen’s openings recently, right? He’s really amazing.

How did you end up co-directing it?

Tetsurô Araki: I had been paying attention to him! At first, it was his work on a Magic: The Gathering PV made at WIT Studio. WIT produced it, and Kamiya was the director. It’s incredible, and Kamiya’s talent left me speechless. I also like watching live-action MVs, and once, I stumbled on an MV for the band Nogizawa 46. It fascinated me, and I wanted to know who directed it, so I looked around, and it was Kamiya again! Basically, Kamiya’s someone whose talent doesn’t know the border between live-action and animation.

So I started wanting to work with him. When Colors started, we decided to split the storyboard between the two of us and work together on the final touches of the visuals as well. Kamiya introduced me to fresh ideas and approaches, and it was so stimulating that I forgot who’s eldest and who’s youngest – I learned so much from him.

Another very important thing for me was working with Mai Yoneyama[7]. Basically, Colors is a project I created just so that I could work with her.

Colors is part of an MV series commissioned by Toho, but where did you get the offer from?

Tetsurô Araki: The offer came to WIT at first. So WIT was looking for someone to do it, and it was right at the time when I was done with Bubble and SpyXFamily, so it was the right moment for me. Also, I took this opportunity to try working with the people I’d like to collaborate more with in the future: I did Colors mostly with people I had never worked with, for instance, on the backgrounds, the photography, also the animators… It was a sort of test for me in that sense.

On SpyXFamily, you directed the opening, while the ending was directed by your good friend Takayuki Hirao[8]. Were you the one to introduce him to the production?

Tetsurô Araki: No! Actually, having me on the opening and Hirao on the ending was all planned by the producer Kazutaka Yamanaka. Hirao and I have known each other since the Madhouse days when we were both production assistants, and since then we’ve been helping out on each other’s works. Yamanaka knew about this, so his plot was to have us as a duo on the opening and ending. It was the first time we did something like that on the same series: we in fact had had few opportunities to do anything like that before. So it became a good memory for us, and it was really fun.

Speaking of Mr. Hirao, I believe the production of God Eater was quite complicated… But just after that, he directed episodes of both Attack on Titan and Kabaneri. How do you think things were for him at the time?

Tetsurô Araki: Well, basically he had left Ufotable and was searching for somewhere to direct something again, and in that meantime, he helped me out on Kabaneri and Attack on Titan seasons 2 and 3. He kept looking for new places and projects, and what resulted from that was the creation of studio CLAP. CLAP was created with Ryôichirô Matsuo, who was a colleague of Hirao and me from the Madhouse days. So when Matsuo created CLAP, Hirao decided he’d settle there, and they started working on Pompo the Cinephile.

There are a lot of lens flares in Pompo as well, aren’t there?

Tetsurô Araki: That’s true. We both love them! But, while Hirao is similar to me and Nakamura in that he doesn’t hesitate to make things flashy, he’s not that fond of such lighting effects. That’s because he received Satoshi Kon’s teaching: Kon didn’t really like using such flashy effects. He was the kind of director who’d use extremely complicated photography techniques but whose films look like there are no effects whatsoever. I understand that approach, which is more refined.

“I like things where the emotions are pushed to their extreme”

Talking of influences and teachings, I believe you’re a big fan of Yoshiyuki Tomino[9]. Is there something you particularly like in his style?

Tetsurô Araki: Rather than his style of direction, it’s how emotional the stories he creates can be. It will sound dumb said like this, but when a character dies, it makes you cry! (laughs) That’s what I love about him, and that’s why I like Tomino’s dark period the most – things like Ideon. I’ll never forget how brutal his works from that time were. It’s different now. Of course, I’m extremely happy that he’s still active, and I was extremely glad to have the opportunity to work with him on Gundam: Reconguista in G. It was a great experience.

Did you learn anything specific from him?

Tetsurô Araki: I realized how impressive he is by working under him. Basically, you have this fight between robots, and at the same time, the characters are talking, and the story progresses – doing both at the same time is so, so difficult! Imagine doing that every episode, every week, for years. That’s not humanly possible. So when I realized he had been doing something that difficult, I was really surprised. I realized I’d never be able to do anything like this.

I’ve heard that Mr. Tomino attached lots of small memos to your storyboards. Is there any one that left a particular impression on you?

Tetsurô Araki: Ah, yes. For example, there was this dialogue scene between two characters, and I had the camera on a high angle and a slow pan. I kept this shot 17 seconds long, and the memo Tomino left for that shot read, “17 seconds, pretty cheeky”. That made me laugh a lot! I didn’t realize it could give out that impression.

Things like that happen all the time to directors: you’re so focused on trying to understand the story that any additional visual information would feel like too much. So you’re trying to use simple visuals and just have a long, simple shot emphasizing the dialogue. But then, it was unexpectedly taken as a “cheeky” move, and it was pretty fun to be confronted with that.

Also, there are the female characters. I really put a lot of effort in them, but Tomino checked things very closely to avoid them being too stereotypical. Basically, what I felt was that he had his own understanding of how women are and that making them cute as they usually are in anime was a no-go. So he would leave notes like “the way she opens her mouth is too small”, or “make the mouth bigger” – he really has his own unique style.

What’s your favorite Tomino female character?

Tetsurô Araki: Aaah, I guess Tomino has very unique tastes, doesn’t he? The women in his series often look insane – at least, they’re always so intense – so it’s really not the kind of characters you’d like to date. Consider characters like Kyôko from Maison Ikkoku: types like that don’t exist in Tomino’s world.

You mentioned Ideon earlier, and I guess that it’s a bit like Attack on Titan in a sense – how intense it always is.

Tetsurô Araki: That’s true. What it all comes down to is that I like things like that where the emotions are pushed to their extreme. Regarding that, there’s something I noticed as we were making Attack on Titan. To make the drama more intense, it’s necessary to raise the stakes: it has to be a big war or have these huge creatures appearing – the drama won’t be as efficient if the story takes place in a normal setting. So I realized that to achieve an effect similar to the one you find in Tomino’s works, you need that kind of cosmic scale.

On Attack on Titan, I felt like we were approaching the intensity of Tomino’s work. Without such an extreme setting, you couldn’t do a story like that, where normal kids end up killing people. You can’t make a high-voltage story without a setting that isn’t as extreme.

But in Tomino’s works, what’s remarkable is that he does both: there are the extreme situations, but also the daily life of the characters.

Tetsurô Araki: You’re absolutely right. What makes Tomino special is how he represents these three things at the same time: extreme situations happening on a huge scale, violent emotions such as love and hate expressing themselves, and the details of how the people going through all that live. I’m trying to reproduce something like that: I want to show extreme situations while keeping the feeling of a realistic depiction of daily life. It’s when both feelings coexist that you truly get a sense of life.

It’s the same in Beat Takeshi’s movies, which I love: there might be extremely violent massacres, but at the same time, the main character is an insignificant old man who just dotes on his children. Being able to do both at the same time is the sign of a great artist and a great entertainer. It’s all about bringing together incompatible things like love and hatred. In that sense, you could say I feel the same about Yoshiyuki Tomino and Beat Takeshi.

“Making an adaptation is about communicating my own personal impressions as a reader”

You’ve been working at Studio WIT for quite a long time. Has it changed a lot in those ten years?

Tetsurô Araki: Yes, it’s become quite big, so a lot of things have changed. Of course, the way work happens is different, but I think the passion of the staff working there is still the same. But with the number of productions increasing, you’ve kinda lost the old atmosphere where everybody was working together on the same thing.

There’s a training program for animators there, are you involved in it?

Tetsurô Araki: Not at all! I’m not an employee at WIT, so I’m not involved at all in their human resources development program. I’m just working with them as an external director, I guess.

Over the course of your career, you’ve managed to turn very popular manga into very popular anime series. What is it that you pay the most attention to when doing an adaptation?

Tetsurô Araki: Hm, I’d say that it’s trying to accentuate the things I found fun when reading the original manga. For instance, Attack on Titan is incredibly scary, but I also found myself laughing in multiple instances. I thought keeping this comedic factor in was very important: when I read the manga, some scenes were disgusting and ridiculous at the same time. So, making a good anime out of it meant recreating that exact same feeling. Basically, making an adaptation is about communicating my own personal impressions as a reader.

Every manga has a very different style, so how do you keep your own individuality when adapting such diverse works?

Tetsurô Araki: Rather than sticking to my own things, I try to put as much energy as I can into making every project a success. I have the things I’m used to doing, and I always think about where I can make use of them, but I also always try to see whether a project is an occasion to try out things I’ve never done before – and if it is, I do my best, try it out and learn new things. So, each project is unique in that sense.

That applies to both adaptations and originals: I consider what it is that I must do every time, and do my best to realize it. That’s how I approach things. It’s good if that leads to something like my own unique style or quirks, but it’s not something I think of beforehand.

Nowadays, whether it’s in Japan or overseas, fans often complain when an adaptation isn’t exactly like the original work. What’s your opinion on this?

Tetsurô Araki: I think such things are bound to happen to some degree. And as I just said, a lot of fans probably want to feel the same things from the anime that they felt from the manga. Since I’m just like them, I can understand why some would get angry. In fact, as a visual artist, I think you can’t make a good adaptation if you don’t love the original work. In other words, if I don’t consider myself a fan of the work I’m doing, I feel like I won’t be able to do it in a satisfying way. I’ve actually experienced it: I’ve already had to adapt manga I didn’t really like, and overall, I wasn’t happy with my work. So I think such situations should be avoided. However, if we take something like Chainsaw Man, while the overall atmosphere was different from the manga, I believe it worked really well as an anime.

Since you’ve done both adaptations and originals, is there any difference in the way you create them?

Tetsurô Araki: It’s totally different! When there’s an original work, you already have an idea of what the road to success is. Whereas for originals, you have no idea about that until the moment people actually start watching your work. You might do some research on that beforehand, but you’re never 100% sure that it’s going to be a hit. Even the greatest geniuses can’t have more than a 50% probability of hitting the jackpot. So, it’s a bet that comes with a lot of risk. But it’s precisely because of that that I want to do it and make things a success.

Generally, there are more difficulties, and the amount of work to put in is higher. So, originals truly are the steepest road. But it’s precisely because of the hardship that I want to do originals.

So, would you like to keep doing originals in the future?

Tetsurô Araki: I would. One thing that hasn’t changed is that I still want to match all the works that left such a strong impression on me when I was young. It’s exactly what I was saying about Tomino, and I want to repeat that experience as much as I can. Over the course of my career, I’ve often watched an episode I directed and thought, “That’s it! That’s exactly what I wanted to achieve!” But it’s just one episode: the series as a whole, or the movie in its entirety, hasn’t reached that point yet. To tell you everything, the movie I’m most satisfied with is Kabaneri: Battle of Unato – I feel like it’s exactly as I wanted it to be. And there have been a few episodes on TV series as well, of course. But it’s never the entire thing.

So taking a work as a whole, there’s both the commercial success and my own feelings about it. I’m not sure how many times I can try it again, but I want to do it as many times as possible.

“Bubble was a sort of recapitulation of all my work up to that point”

I believe you got the offer for Bubble from producer Genki Kawamura[10].

Tetsurô Araki: Pretty much, yes. Kawamura wanted to do something with me at WIT.

How did you react when he contacted you?

Tetsurô Araki: I was really down with it! The audience for it wasn’t clearly defined from the start, so it made me want to learn more about what I can and cannot do, what people besides me expect from my films. As an external viewer and reviewer, he taught me so much.

Could you get into more detail? How did Mr. Kawamura help you and the staff do things you had never done before?

Tetsurô Araki: A fun thing that happened is that we spent around six months discussing what kind of story we should make. The first thing I had suggested was pretty similar to my past work: it was a story with monsters attacking humans. Kawamura noticed that, so he suggested doing something totally different from what I had done previously.

To answer his remark, I suggested a plan for something like “The Little Mermaid in the future in the middle of ruins” – we spent something like six months before reaching that point. That proposal was accepted, but even though it was my idea, I had no idea how to make it a reality. Kawamura brought me to new places, but he also made me face new problems, and I was getting pretty lost. But that’s Kawamura’s method: getting creators lost and expecting them to open new doors in such a situation. Kawamura is someone amazing, so it really worked out.

So would you like to work with him again?

Tetsurô Araki: I would! If the occasion ever arises again, I’d love to.

I’ve heard that, on Bubble, you absolutely wanted to work with Takeshi Obata[11].

Tetsurô Araki: Maybe that’s a bit strong. It’s just that “It had to be him” is a good punchline. And it’s true that I really like his work.

But basically, for me, Bubble was a sort of recapitulation of all my work up to that point. So, I wanted to work again with the people I knew: the animators, the background artists, the actors… And, well, I thought that Takeshi Obata, who had done the original designs for my first TV series, Death Note, needed to be here.

Back then, I already loved Obata’s art, but I don’t think the adaptation did justice to how great his drawings are. But for Bubble, I thought that with the people I had brought together, we should be able to match the quality of Obata’s art.

It’s true that Obata’s drawings are great, but they must be hard to reproduce.

Tetsurô Araki: You’re exactly right. He’s just too good! It’s just impossible for every shot to reach that quality, so everything risks ending up looking like Death Note. Just properly drawing the most important cuts was a big weight. I thought I wanted every drawing to look just as beautiful as in the manga, but I had to give up many times because it was simply impossible.

Since we’re talking about the staff, all of the main animators are people who had worked a lot with you previously, as you said, except for Shû Sugita. How did he get to that position?

Tetsurô Araki: Well, he worked on the Kabaneri film, and I was extremely happy with his work. There was that, and also Yamanaka, the producer who’s always been taking charge of my works at WIT, who also likes Sugita. Sugita’s really adorable; he’s a great person. So Yamanaka really wanted to invite him. Sugita seems to like what I do as well, so we’re really compatible.

Talking about “main animators”, what’s the meaning of that credit?

Tetsurô Araki: At least in WIT, there’s this awareness that it’s hard to make out who’s important by just reading the animation credits. So if we put certain people in the opening credits, it shows even by a little bit that they’re valuable – it’s sort of like a message from the producers to the animators, saying, “We’re counting on you!” That’s what “main animator” is about. They’re not animation directors; they’re not in charge of designs or anything. But without them, the production wouldn’t have happened the way it did, so we use that credit as a message. It’s probably the same in other studios.

All our thanks go to Mr. Araki, as always, for his kindness and for his time.

Interview by Matteo Watzky and Dimitri Seraki.

Transcription by Antoine Jobard.

Translation, introduction, and notes by Matteo Watzky.

Notes

This article would not have been possible without the help of our patrons! If you like what you read, please support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Oshi no Ko & (Mis)Communication – Short Interview with Aka Akasaka and Mengo Yokoyari

The Oshi no Ko manga, which recently ended its publication, was created through the association of two successful authors, Aka Akasaka, mangaka of the hit love comedy Kaguya-sama: Love Is War, and Mengo Yokoyari, creator of Scum's Wish. During their visit at the...

Ideon is the Ego’s death – Yoshiyuki Tomino Interview [Niigata International Animation Film Festival 2024]

Yoshiyuki Tomino is, without any doubt, one of the most famous and important directors in anime history. Not just one of the creators of Gundam, he is an incredibly prolific creator whose work impacted both robot anime and science-fiction in general. It was during...

“Film festivals are about meetings and discoveries” – Interview with Tarô Maki, Niigata International Animation Film Festival General Producer

As the representative director of planning company Genco, Tarô Maki has been a major figure in the Japanese animation industry for decades. This is due in no part to his role as a producer on some of anime’s greatest successes, notably in the theaters, with films...

Trackbacks/Pingbacks