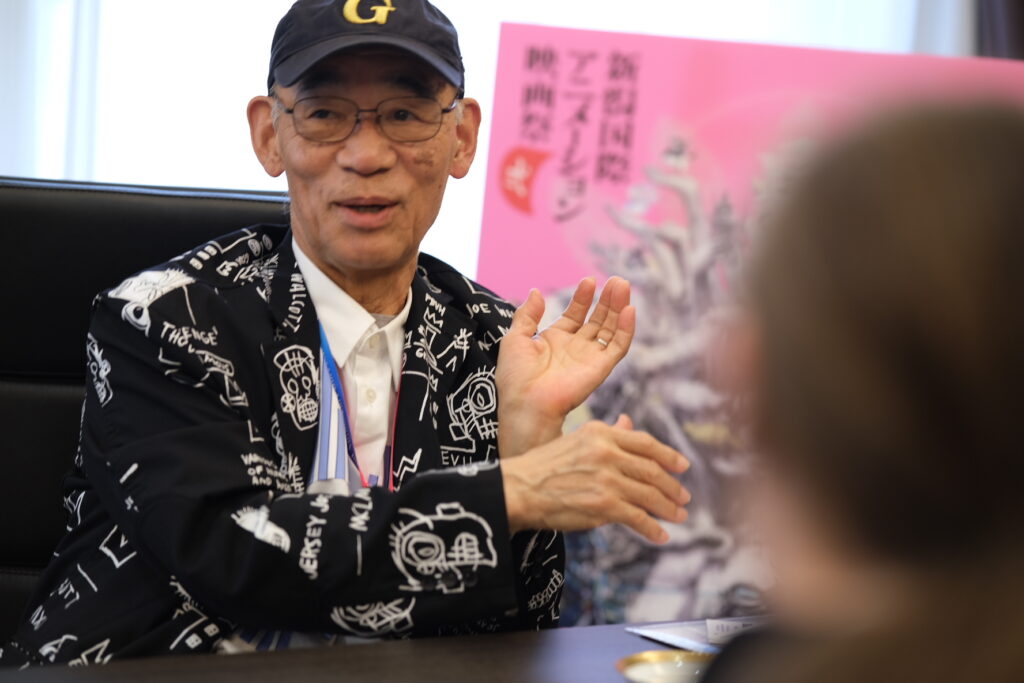

At this year’s Paris Japan Expo, alongside Character Designer and animator Junichi Hayama, came his friend and colleague, Mr. Mamoru Yokota. Mr. Yokota is a well-established and respected artist both as an animator and an illustrator. In the early 2000s, he also worked on many Adult Video Games, most notably on the Magical Canaan series and other games from the Terios brand. Many might know the promotional illustrations he has drawn for the show Neon Genesis Evangelion or his contributions as an animation director on Death Note or, more recently, on Dragon Quest: The Adventure of Dai.

We took this opportunity to discuss with Mr. Yokota what led him to work in animation, the whereabouts of the many positions he has occupied, and his love for fighting games and pro wrestling.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

“I had the choice of either becoming a delinquent or finding something to get me out of there.”

First, I’d like to ask about something from before you went pro. It is said that when you were still in junior high, you visited Comiket with a friend, and there you found some of your illustrations published without your knowledge. Is this true? And if it is, has it shaped your career somehow?

Mamoru Yokota: Ah, that’s wrong. When I was younger, I lived in the Edogawa district of Tokyo. It’s a district known for having a lot of delinquents at the time; it was really bad (laughs). I was friends with the brother of a game center’s owner, and he took care of me and allowed me to stay and play even after closing hours. My father died when I was young, and I was raised by my mother. It was the other way for him, but we shared the experience of being raised by a single parent, so he and his brother really took care of me. One day, he brought me to his room on the second floor of that game center, saying, “Well, you seem to like games and that kind of stuff.” That guy was a full-on otaku. That way, he introduced me to many artists and otaku culture, like Shingo Araki[1] and Kazuo Komatsubara[2] , who are incredible animators, to Kamen Rider and the works of Shotaro Ishinomori[3] , and even the music of Chumei Watanabe[4] and Shunsuke Kikuchi[5] . In a way, this had a massive impact on my career. Since I lived in such an ill-famed neighborhood, I had the choice of either following in the footsteps of my buddies and becoming a delinquent or finding something else to do to get me out of there. That’s why I started drawing. And one day, the older brother who owned the game center noticed that I liked drawing, so he asked me to make some illustrations, and these were displayed in the game center (laughs). And later, they were gathered and published in a doujinshi.

And that’s from when you were still in school? How old were you then? 15 or 16?

Mamoru Yokota: Noooo, more like 12 or 13. But at the time, I knew nothing of that world, so my friend decided to take me to Comiket. We just hopped on our bikes and went there. It was one hell of a place. It made a massive impact on me, and I had an epiphany: drawing is what I want to do with my life.

You know, right now, there’s this popular manga, Tokyo Revengers. It’s a story about delinquents. Well, the guys I used to hang out with at the time were the real-life version of the characters of that story.

Well, we’ll have to change your Wikipedia page, then (laughs). So after that, you studied in a vocational school, and you went to work in animation. What led you to decide to become an animator?

Mamoru Yokota: That’s not it! As I said, I was raised only by my mother. When my father died, he had a lot of debt, and my mother and I inherited all of it. I worked as a cook at a Chinese restaurant for several years to repay that debt. When we finally paid it back, my mother told me: “You worked hard, now do what you want with your life.”

At the time, I only had two choices; either continue to work as a cook or do something else entirely. I was tired of being a cook, and I liked drawing. That’s why I entered a vocational school to learn drawing. I didn’t know anything about art and went to an animation school. I paid the tuition with some money that I had left after paying back all the debt.

After graduating, when you did your first work on Transformers, were you freelance? Or did you enter a studio?

Mamoru Yokota: Usually, if you do it right, it takes two years to graduate from a vocational school. But I was awful at studying. They would teach lots of techniques like sketching and perspective and whatnot; it was such a bother. While reading an anime magazine, I stumbled upon a job offer from a very small animation studio. It wasn’t like today’s sparkling places; it was really gloomy. So I applied and started working there while still going to school at the same time. And when I graduated, I was already a member. Really, it was no good and ridiculously small. There were like four people working there, but that’s where I started my career as an animator.

Do you remember the name of that studio?

Mamoru Yokota: I’d rather not tell. (laughs) It doesn’t exist anymore, anyway. Still, it had good relationships with studios such as Toei and Sunrise. That’s how I ended up doing my first job as a professional animator as an in-betweener on Transformers Masterforce[6] . I worked on the character of God Ginrai, who has the body of Optimus Prime, which combines with other parts. It was so hard that I wanted to quit whenever I had to draw it. After that, I worked on Transformers Victory[7] . Our boss had the bad habit of taking in work and disappearing (laughs). He’d take the job and run away, so we were on our own and had to do everything ourselves. We were just four in the studio, but since the boss wasn’t doing any work, we were only two or three people doing everything. It was quite something.

And that’s how my career started! Usually, an animator starts as an in-betweener, gets promoted to key animator, and eventually becomes an animation director if all goes well. But things were such a mess that we couldn’t just focus on our drawing and had to do a bit of everything. Someone from the production staff of our contractor would come and just tell us to do this or that job in the boss’ place since he wasn’t there, so we even had to handle the management. Talking about it now is fun, but actually, things were so hard for everyone. We were taking hits as if we were Saiyans.

It happened from the moment you started working there?

Mamoru Yokota: From the start, I worked on every function. I had to multitask.

“We weren’t very big or famous, but our staff was good.”

In 1990 you created your own structure, Studio Line. How did that happen?

Mamoru Yokota: Well, the studio where I used to work at was really bad, so I decided to go freelance. At some point, that studio finally went under, and the boss came to ask me for help and wanted to make me work some more. I had been working on video games thanks to a friend: I worked with Square Enix, on PC games, and so on… I was doing all kinds of stuff and enjoying myself quite a lot. At that time, a student of my friend was looking for work and asked me to do an interview, but I told him I didn’t have a studio, so I turned him down. Then one day, I talked with one of my older colleagues, a very talented animator with a good sense of business but who didn’t really know how to negotiate, so he offered to create a studio together. With him and a group of older animators, we wanted to create our place and raise our own students. And just at that moment, we had a big chance: a cel painting studio went under, and they offered to give us all their material, desks and everything. So we finally did it. But then all the other guys started saying, “I’m not good at this, I can’t teach youngsters, I’m quitting.” It ended up being just me and two newbies (laughs). I was really lost, but that’s how it began.

I had to do everything again: I was teaching the youngsters, doing the key animation, receiving the in-betweens and checking them… It was really hard, but progressively I gathered good friends around me, and it became a studio proper.

So that’s how Line became an LLC?

Mamoru Yokota: As I said, I didn’t want to create a company at first. That only started because the older guys asked me to, but when they all left, I didn’t really know what to do. Things were really awful. I got swindled or betrayed multiple times by game companies. I wanted to quit because I was all alone in a studio that I ended up leading even though I didn’t want to. I was about to give up, but people progressively gathered and wanted to go on, so I decided to do things the proper way and created an LLC.

That’s one hell of a story (laughs).

Mamoru Yokota: All that time, it really wasn’t worth being called a company. It was a sort of melting pot with some people working on animation, some others on games… It was like a band of friends who played together at the game center got together in a single place.

The animators were pretty quiet, but not the video game people. We weren’t very big or famous, but our staff was good, so we could do very good work.

Talking about video games, can you tell us about the Capcom Girls illustration project you were involved in?

Mamoru Yokota: Well, at the time, there was this magazine called Gamest which also worked on a magazine called Girls Island. I was a big fan of fighting games, and back then, I had even bought my own arcade. I think that, at that time, video games were very popular with illustrators. Mangaka often read it and liked it a lot.

That’s impressive (laughs). And on Street Fighter, what characters did you play with?

Mamoru Yokota: Hmm, mostly Ryu, but in fact, I’d play with every character except the women (laughs). I wanted to play with the girls, but in the end, I’d mostly end up choosing the guys.

“I’ll keep doing my best and do things my way!”

Changing the subject, I know you are a big fan of mecha anime and Araki Shingo. Have you had the opportunity to watch the pilot of Gekishin Jagrion[10] ? [Mr. Yokota bursts out laughing hearing the name]

Mamoru Yokota: Of course I have! The animation director Eisaku Inoue[11] talked to me about it since we were both working with Toei. I wish it would have been made as a TV series because I also wanted to work on it as an animation director.

That’s because you really like mecha, right?

Mamoru Yokota: In my first studio, we had to work on whatever came, be it mecha, characters, action… So rather than saying that I like it or that I’m good at it, I just had to do it! It’s the same with Dai no Daibouken[12] , which I’m working on now; it’s always a new challenge. You know, when I was working on video games, people would say I was good at drawing pretty girls, cool guys, or whatever. Or when I worked on Crying Freeman[13] in Toei, there were yakuza and stuff, and I did that as well. So, of course, I was influenced by the people we talked about, like Shingo Araki or Kazuo Komatsubara, and I’d really like to become as good as them. It might seem impossible, but I will keep doing my best and do things my way!

Talking about Kazuo Komatsubara, is that why you worked on Tiger Mask W?[14]

Mamoru Yokota: Oh no, not at all. Hayama[15] and Kagawa[16] were participating, but the schedule was pretty tight, so the quality couldn’t meet their standard. They asked for help, and even though I was really busy, I joined them because I greatly respect them.

Talking about Hayama and Kagawa, you’re quite friends with that team from Monsieur Onion[17] , right?

Mamoru Yokota: Right. I wasn’t a member of Monsieur Onion or anything. It’s just that we have multiple acquaintances in common and often go out to drink together or something. There isn’t anything deep behind it.

Oh, so you’re mostly drinking buddies?

Mamoru Yokota: Yes, that’s it.

On Tiger Mask W, what part did you help with?

Mamoru Yokota: I was on the penultimate episode during the last fight scene of the show. You know, the story ends in the penultimate episode when Tiger Mask defeats The Third, and the final episode is that story about the female Tiger Mask coming in. The fight against The Third was made by Mr. Shida[18] , but the rest is mostly Hayama and Kagawa’s work as animation directors.

And what do you think about the female Tiger Mask?

Mamoru Yokota: Ooooh, that girl – what’s her name? Tiger Dream or something? She’s a real fighter, so I like watching the fights as long as they are enjoyable! I’m a big pro wrestling fan, you know. I even have friends who are pro wrestlers.

So who are your favorite wrestlers?

Mamoru Yokota: My favorite wrestlers, huh… I’d say old wrestlers like Hulk Hogan… And, of course, I love Tiger Mask. Especially Satoru Sayama[19] , who was the first-generation Tiger Mask. He was really a genius of movement. In pro wrestling, the steps and movements differ from karate, boxing, or stuff like that… you really feel the weight. It’s amazing to watch. And then I also like the second-generation Tiger Mask, Mitsuharu Misawa[20] . He was the first heavy-weight Tiger Mask wrestler. You know, he took the mask off at some point and created his own wrestling league.

“Baba’s dream was the most important.”

Going back to your own work, you’ve also been a producer for some time. I’d like to ask about the Kanon[21] anime you produced. Was it because you were involved in the game or something?

Mamoru Yokota: Oh, that’s because I’m an old friend of Mr. Baba, the boss of Visual Arts, the company that made Kanon. One day, he told me he wanted to make an anime adaptation and asked for advice. So we went to talk with the boss from Frontier Works and a higher-up from Movic about the project. Baba didn’t want it to be aired on satellite broadcasting, so when we went to talk with TBS, there was a problem with that. That’s why we ended up making it in Toei: it was simply the only place that could broadcast it through terrestrial signal and would air it on a public channel. Baba was very happy with that and the fact that it would be broadcast on local channels as well, so we settled there, and the work started at Toei. It was the only place that could do it, you know. Well, I’m saying all that, and maybe kids like you don’t get it, but that’s how it is. Baba’s dream was the most important.

And then, a few years later, Kyoto Animation made their own version.

Mamoru Yokota: Yeah, well, Toei had done their own thing properly, but KyoAni wanted to do their own one as well, but that wasn’t broadcast on a public channel. At the time, people came in to ask me what to do between Kanon and Air[22] , and while I wasn’t there, another producer said that it’d be better to make a movie version for Air, which ended up happening. The reason for that is that there weren’t enough people available to make a TV series, and in that way, the Kanon team could work on Air as well, notably Yoichi Onishi[23] , who had done some good work on the TV show.

The Air movie was directed by Osamu Dezaki[24] . How was he brought in?

Mamoru Yokota: Well, at first, I wanted the director to be Tomomi Mochizuki[25] , you know, the one who worked on Urusei Yatsura[26] and Maison Ikkoku[27] . But when he saw that, my best friend, a producer called Hoshino, told me: “that’s ok if you want him, but Yoko-chan, aren’t you a fan of Dezaki?” and invited him. I was really happy, but I wasn’t really sure it was Dezaki’s type of thing! But Dezaki came in and said, “it’s popular, isn’t it?” (laughs), and I was like, “uh, well, yeah?” (laughs). You know, at home, I had a place with a PS2 and a PlayStation, and when Dezaki saw them, he said, “I don’t know anything about this stuff, but it’s really nice!” and just after that, he asked me to bring him the entire scenario (laughs). Actually, the first thing we had him read was written by the person who wrote the Kanon drama CD. I rewrote a lot of it myself because I thought it’d be wrong if I brought it as is to Mr. Dezaki. And then Mr. Dezaki did his own changes, I did another check, and we started the production in earnest.

Among your many activities, you’ve also been a manga editor, right?

Mamoru Yokota: Oh no, I wasn’t an editor, but I worked on an anthology with the chief editor to check the copyrights and the scripts of the video games that were adapted, and I gathered some of the artists who worked on it.

What was the title of the anthology?

Mamoru Yokota: Don’t expect me to remember that! It’s such an old story! I don’t really remember the companies either… there was Movic and Soft Bank…

“I really miss how beautiful the old designs were”

Since we’ve talked a lot about arcade games, can you tell us about your favorites?

Mamoru Yokota: I love the Street Fighter series, especially until III. Street Fighter IV is also really nice, but I just love pixel graphics. And I also love things like Muscle Bomber.[28]

What’s that?

Mamoru Yokota: Wait, you don’t know about it? It’s a fighting game by Capcom! It’s got the characters from Final Fight[29] like Haggar!

Ah, I know about Final Fight, but…

Mamoru Yokota: Then you know about Haggar, right? You can play him in Muscle Bomber.

As for me, I really like Kunio-kun[30] .

Mamoru Yokota: Kunio-kun?? Isn’t that super old? (laughs) I used to play it at the game center.

Then let’s go together!

Mamoru Yokota: We can’t do that now (laughs). Since we’re talking about old stuff, there are also things like Galactic Warriors or Appooooh. These were really fighting games before fighting games existed.

By the way, did you try out Street Fighter VI?

Mamoru Yokota: Not yet!

You could try the demo at Japan Expo!

Mamoru Yokota: Oh, is that right? Well, I thought that Street Fighter V’s system was really annoying, so I didn’t play a lot. I thought I’d give VI a chance, but Chun-Li isn’t cute at all anymore, right?

Is that so?

Mamoru Yokota: She’s not cute… She’s old now, that’s bad. I really miss how beautiful the initial designs were. I can’t tell yet, but I don’t know if I’ll play VI because none of the characters makes my heart tingle in that way. But well, if I play it, maybe I’ll like it.

Are you an acquaintance of Akiman’s?

Mamoru Yokota: I know about him, and I more-or-less know his face, but he’s much older and more experienced than I am. I’m roughly Hayama’s age.

You know, talking about this, I’ve always wanted to work on fighting games. Do you know about Fighter’s History Dynamite[31]? Well, I was asked to work on the second one since I had worked on another Sega Saturn game before, and they even offered a lot of money for it, but I refused. But now nobody makes 2D fighting games anymore. I’d like to make a fighting game where you don’t fight with weird beams or swords or whatever but with your fists.

And what’s your favorite fighting game?

Mamoru Yokota: (Thinks) Well, there’s the Street Fighter series… and my favorite in it has got to be Super Street Fighter II X.

Thank you for your time! Any last words?

Mamoru Yokota: You know, with Hayama, we’re often invited to events and cons. We’ll soon go to something in England, and I’m going to Switzerland in September. I forgot the name, but it was supposed to happen in March 2019, but it kept being delayed. Work is really a big adventure!

Interview by Dimitri Seraki, Matteo Watzky and Ludovic Joyet.

Interpreter: Pierre Giner

Translation: Mathilde Nouaillier

We wish to thank Mr. Yokota for his time and kindness, as well as the staff of Paris Japan Expo who helped us set up this interview, especially Mr. Thomas Quinn as well as Maison Wa who gave us the opportunity to extend our interview.

Notes

[1] Shingo Araki (1938 – 2011). Animator, animation director, and character designer. He is mostly remembered now for his character designs on Saint Seiya. He was active throughout all of anime history, on works such as Star of the Giants, Ashita no Joe, Rose of Versailles… His style has influenced artists throughout the ages.

[2] Kazuo Komatsubara (1943 – 2000). Animation director and character designer from Studio Oh! Production. One of the most influential artists to work for Toei in the 70s. He is especially famous for his work on Devilman, Getter Robo, Galaxy Express 999, and Space Pirate Captain Harlock.

[3] Shotaro Ishinomori (1938 – 1998). Famous and extremely prolific manga artist, known, among other things, for his collaboration with studio Toei on tokusatsu series such as Kamen Rider and the Super Sentai franchise.

[4] Chumei Watanabe (Michiaki Watanabe) (1925 – 2022). Composer for anime and tokusatsu series. Some famous and representative works of his are the openings for the series Space Detective Gavan, Android Kikaider, Mazinger Z, and Saikyo Robo Daioja. His work is most recognizable by the use of onomatopoeias such as “DADADDA” or “GANGAGAN” and children’s choirs which are heavily associated with 70s anime openings.

[5] Shunsuke Kikuchi (1931 – 2021). Famous and influential composer for anime and tokusatsu series. His most notable contributions include series such as Getter Robo, Kamen Rider, Doraemon, and Dragonball.

[6] Transformers Super-God Masterforce. 1988 – 1989, Toei Animation, TV series, dir. Tetsuo Imazawa. The sequel to the Toei Animation series Transformers: The Headmasters. The particularity of this series is that it portrays humans, the Godmasters, who transform into robots by merging with their robot counterparts called a Transtector. For example, Ginrai, the protagonist, is the Godmaster of the body of Optimus Prime.

[7] Transformers Victory. 1989, Toei Animation, TV Series, dir. Yoshikata Nitta. The sequel to the Toei Animation series Transformers Super-God Masterforce. Contrary to the previous series, where combat would focus on guns and long-range weapons, this show focuses on fights with close-range weapons such as swords. Several elements of the show went to influence the notorious Brave series

[8] Street Fighter Series. 1987 – 2022, Video Game Series, Capcom. One of the most notorious fighting game series and the flagship of Japanese video game company Capcom. It includes over 30 mainline games released on various arcades and home systems.

[9] The King of Fighters Series. 1994 – 2022, Video Game Series, SNK. A fighting game series that gathers characters from other SNK games such as Fatal Fury and Art of Fighting. The series includes about 20 games released on various arcades and home systems.

[10] Gekishin Jagrion. 1990, Toei Animation, Pilot film, dir. Noriyo Sasaki. A 3 minutes and 30 seconds pilot film for a TV Series that was never released. It is related to Toei’s multiple abandoned projects to revive the Mazinger Z and UFO Grendizer franchises. The pilot presents 5 boys who pilot transformable robots whose style is very reminiscing of Grendizer and Toei’s Getter Robo Go in a setting using Southern American mythology such as the Nazca lines. Character designs were done by Shingo Araki and look very similar to his work on Saint Seiya, and Eisaku Inoue was the animation director for the pilot episode.

[11] Eisaku Inoue ( ? – ). Animator and animation director affiliated with Toei Animation, whose major works include Saint Seiya, One Piece, and Tiger Mask W.

[12] Dragon Quest: The Adventure of Dai. 2020 – 2022, Toei Animation, TV Series, dir. Kazuya Karasawa. The second adaptation of the hit Shonen Jump adventure manga based on the Dragon Quest video game franchise. The first adaptation, also produced by Toei Animation, was broadcast in 1991. It follows Dai and his party in their quest to defeat the Demon King Hadlar.

[13] Crying Freeman. 1988 – 1994, Toei Animation, OVA, dir. Nishio Daisuke, Nobutaka Nishizawa, Jouhei Matsuura, Shigeyasu Yamauchi. Anime adaptation of the action gekiga by Kazuo Koike and Ryouichi Ikegami. It tells the story of Yo Hinomura, an assassin for the Chinese mafia who sheds tears every time he kills someone.

[14] Tiger Mask W. 2016 – 2017, Toei Animation, TV Series, dir. Toshiaki Komura. A sequel to the first two anime series of Tiger Mask. The series follows Naoto Azuma, a pro-wrestler who, to avenge his paralyzed coach, takes up the persona of Tiger Mask to fight the malignant Tiger’s Den organization. The series shines through its well-choreographed fights and animation by Toei Animation veterans such as Naotoshi Shida.

[15] Junichi Hayama (1965 – ). Animator and Character Designer trained at Monsieur Onion Production who got recognized for his work on Fist of the North Star 2. He is considered the disciple of Masami Suda. Now works freelance. If you want to learn more, you can read our interview with Junichi Hayama.

[16] Hisashi Kagawa (1965 – ). Animator and Character Designer trained at Monsieur Onion Productions under Junichi Hayama. He is well known and respected for his very recognizable work as an animation director on Sailor Moon and his character designs for Fresh Pretty Cure! Although he has been freelance since the 2000s, he is mostly affiliated with Toei Animation productions. If you want to learn more, you can read our interview with Hisashi Kagawa.

[17] Monsier Onion Productions. An anime studio mainly taking subcontracting work for Toei Animation in the 80s. The working conditions were quite erratic as its president had no experience running a company, and the pay they offered for each cut was one of the lowest in the industry at the time. The company was taken over in 1997 and continues business under the name Studio Kagura.

[18] Naotoshi Shida ( ? – ). One of the most important animators working with Toei Animation, he is most known for his contributions to the Dragon Ball, One Piece, and Precure series. His extremely dynamic fight scenes are remarkable for their idiosyncratic, very fluid sense of action.

[19] Satoru Sayama (1957 – ). Japanese Pro Wrestler and MMA fighter nicknamed the “Bruce Lee of wrestling” and known as a pioneer of MMA. From 1981 to 1983, he fights in the New Japan Pro-Wrestling league as Tiger Mask, wearing a costume identical to Tiger Mask Nisei. In 1985 he founded the Shooto Association, which organized some of the first MMA competitions.

[20] Mitsuharu Misawa (1962 – 2009). Japanese Pro Wrestler who impersonated Tiger Mask between 1984 and 1990 and was the first Tiger Mask to fight in the heavyweight league. After succeeding Shohei Baba as president of the All Japan Pro Wrestling promotion in 1999, he left to form his own promotion, the Pro Wrestling Noah.

[21] Kanon. 1999 video game, Key & Visual Arts, dir. Naoki Hisaya. The first visual novel released by video game studio Key. It was an instant hit and became one of the best-selling games in Japan shortly after it came out. It received two TV anime adaptations, one by Toei Animation in 2002 and one by Kyoto Animation in 2006.

[22] Air. 2000 video game, Key & Visual Arts, dir. Jun Maeda. The follow-up to Kanon, it was also one of the best-selling games of its time and received two animated adaptations in 2005: a TV series by Kyoto Animation and a feature-length movie by Toei Animation.

[23] Yoichi Onishi ( ? – ). Animation director and character designer, mostly affiliated with Toei in the late 1990s and early 2000s. He was the character designer and chief animation director on both Kanon and Air.

[24] Osamu Dezaki (1943 – 2011). One of the most important directors in anime history, this extremely prolific artist was active from the 1960s to the 2000s. His most famous works include Ashita no Joe, Aim for the Ace!, Dear Brother… and Black Jack. He is known for pioneering an expressionist style relying on elaborate still frames and complex cinematography.

[25] Tomomi Mochizuki (1958 – ). Anime director affiliated with Asia Do for most of his career. The episodes he directed on Kimagure Orange Road and Creamy Mami, the Magic Angel show his unique directing style the best, characterized by heavy reliance on panning, high camera positions, and 360º camera movements. He was also in charge of directing the 1993 Studio Ghibli telefilm Ocean Waves.

[26] Urusei Yatsura. 1981 – 1986, Studio Pierrot & Studio Deen, dir. Mamoru Oshii & Kazuo Yamazaki. The first adaptation of a Rumiko Takahashi manga, this crazy SF comedy notably propelled director Mamoru Oshii to fame in Japan and was a creative powerhouse throughout most of its run.

[27] Maison Ikkoku. 1986 – 1988, Studio Deen, TV series, dir. Kazuo Yamazaki, Naoyuki Yoshinaga, Takashi Anno. Another adaptation of a Rumiko Takahashi romantic comedy following the misadventures of college applicant Yusaku Godai, his co-tenants in the boarding house Maison Ikkoku, and his love story with landlord Kyoko Otonashi. The series remains well-appreciated to this day and is considered one of the best manga adaptations ever made. The 1988 movie was directed by Tomomi Mochizuki.

[28] Muscle Bomber (Saturday Night Slam Masters). 1993, Video Game, Capcom. An arcade fighting game released by Capcom that features characters from their game Final Fight and character designs by Fist of the North Stars author Tetsuo Hara.

[29] Final Fight. 1989, Capcom. A famous arcade Beat’em up game series developed by Capcom. It was ported to various home systems over the years and has had multiple sequels.

[30] Nekketsu Kouha Kunio-kun (Renegade). 1986, Video Game, Technos Japan. The first game from the Beat’em up video game series River City. One takes control of Kunio, a high school delinquent, who fights off other delinquents to avenge his friend Hiroshi. The River City series includes over 50 games covering various genres, from beat’em ups to sports games.

[31] Fighter’s History Dynamite (Karnov’s Revenge). 1994, Video Game, Data East. The second game in the Fighter’s History series a fighting game with many similarities to Street Fighter. So much so that Capcom sued Data East over the similarities between the two games.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Oshi no Ko & (Mis)Communication – Short Interview with Aka Akasaka and Mengo Yokoyari

The Oshi no Ko manga, which recently ended its publication, was created through the association of two successful authors, Aka Akasaka, mangaka of the hit love comedy Kaguya-sama: Love Is War, and Mengo Yokoyari, creator of Scum's Wish. During their visit at the...

Ideon is the Ego’s death – Yoshiyuki Tomino Interview [Niigata International Animation Film Festival 2024]

Yoshiyuki Tomino is, without any doubt, one of the most famous and important directors in anime history. Not just one of the creators of Gundam, he is an incredibly prolific creator whose work impacted both robot anime and science-fiction in general. It was during...

“Film festivals are about meetings and discoveries” – Interview with Tarô Maki, Niigata International Animation Film Festival General Producer

As the representative director of planning company Genco, Tarô Maki has been a major figure in the Japanese animation industry for decades. This is due in no part to his role as a producer on some of anime’s greatest successes, notably in the theaters, with films...

What an interesting read! I’m a huge fan of this man’s work. His character designs are incredible.