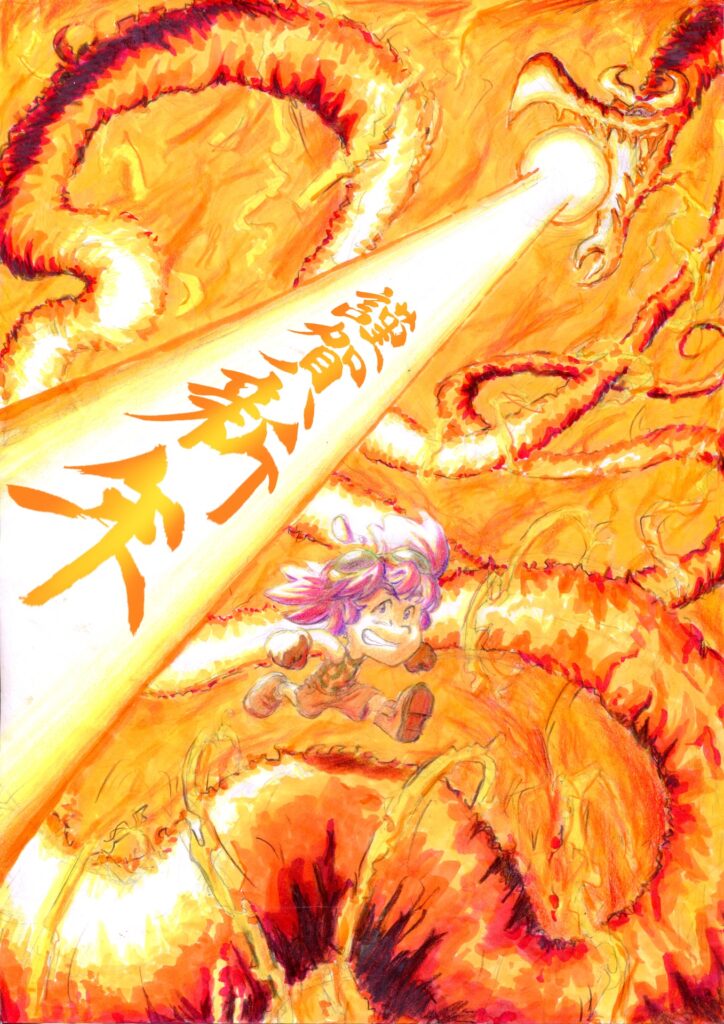

Aside from the world-famous Annecy Festival, many smaller animation-related events take place in France over the years. One of the most interesting ones is the Carrefour du Cinéma d’Animation (Crossroads of Animation Film), held in Paris in late November. In 2023, it celebrated its 20th anniversary and gathered quite an interesting lineup. Among them was Benoît Chieux, a veteran French animator and director of the then unreleased Sirocco and the Kingdom of the Winds. As the ambassador of this year’s edition of the Carrefour, he designed the poster and gave a long talk about his career, a sort of personal history of decades of French animation.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

Chieux’ childhood animated love was Disney, particularly movies like Robin Hood and The Rescuers. The latter was especially shocking for its themes: its a very dark film, the kind of animated film you wouldn’t be able to find funding for nowadays. Another one of his early aesthetic experience was Tron, introducing him to other spheres such as Moebius’ work and the Alien franchise.

Chieux defines his childhood by the myriad of universes he came across. He noted that he was a fervent reader of the Okapi magazine during its first years, when it was spearheaded by Denys Prache. Chieux particularly liked how bold the magazine was: it was filled with great abstract illustrations and great content, even though it was aimed at kids. Illustrator Nicole Claveloux did wonders at inspiring the young Chieux. This love for drawings explains why he’s mainly interested in 2D animation.

Chieux also mentioned Paul Grimault’s The King and the Mockingbird, one of the great classics of French animation, as a fundamental work for him. He went to see it in the theater with his family, and remembers being engulfed in the movie. While his parents weren’t sure what to think of it, he was completely charmed. Chieux thinks that even today, it’s still a very unique proposition, especially in the way it uses silence and tries to awaken the viewer’s sensibility.

Then, Chieux mentioned René Laloux’s work, Fantastic Planet and Time Masters. Moebius’ presence on them is very obvious and important for the director. To this day, he fondly remembers finding a copy of Moebius’ original storyboard in a flea market in Lille, in the north of France. He learned a lot from it, from sketching to shot composition.

When talking about these movies, Chieux remembered his time in high school, where he pursued a Brevet de Dessinateur, i.e. followed special art courses: 20 hours of drawing per week, with academic work on the side. In his last year, an animation class was created, which he joined. The teacher in charge didn’t know anything about it, so both teacher and students learned about it in tandem. For Chieux, this is a great educational method, as it centers the whole process around the teacher rather than under them. The class went to see films in the cinema and visited animation studios. The final exam was quite peculiar, as they had to use gouache on an actual cel, which is way harder than it seems! The paint layer has to be completely uniform, and thick enough for it not to be transparent. Without this program, Chieux may not have entered a career of animation.

While acknowledging the advantages of digital, the director was a bit nostalgic about the analog and cel days, noting that, when everything’s done digitally, it’s sometimes hard to remember just how much effort a picture needs.

The director entered the world of art and animation by joining the Émile Cohl art school, not long after it had opened its doors. The school’s goal was to provide a place to teachers that had studied fine arts before May 1968: the social upheaval that happened in those days made society progress in a lot of ways, but it did terrible damage to the art world. Indeed, it had killed academic art and training such as perspective or anatomical studies. Private schools had to take the mantle, and Emile Cohl wanted to be a part of it. The courses consisted of 45 hours of drawing per week, with a heavy focus on anatomy.

After graduating, Chieux was scouted by one of his teachers and joined his animation studio, Folimage in the early 1990s. There, he ended up working on TV series such as Le Bonheur de la Vie and Ma Petite Planète Chérie, both children’s shows that were quite daring at the time. Le Bonheur de la Vie was a sex-ed show made at a time when puritanism was at its peak in France, with actual terror attacks on cinemas. It didn’t air a lot in its home market, but found some success in Italy. Ma Petite Planète Chérie was about ecology. Chieux is still quite proud of his work on it, but laments how relevant it still is! He remembers the episode about nuclear power being quite controversial at its release, and notes that it’d still be controversial today. Chieux believes that you don’t need to strictly spew platitudes when you build stories for kids. What’s most important is to share the children’s point of view. In doing so, you can still tell the stories you want to tell.

Then came one of Chieux’ first real creative experience, on the short L’Enfant au Grelot (Charlie’s Christmas) in 1998, where he served as scriptwriter and art director. He had a lot of trouble finding something original for the visuals. But, pushed by his colleagues, he found inspiration in silent cinema, or reference iconic French comedy actor and director Jacques Tati to design the postman, one of the short’s main characters. Chieux believes that silent cinema is an invaluable inspiration for animators, as it deals with very similar issues by using the characters’ bodies and movement as much as possible.

Chieux didn’t realize what he wanted to go for at the time, and still doesn’t fully grasp how important this movie was, but he understands that it had an influence on a lot of people. But even more than L’Enfant au Grelot, Spud and the Vegetable Garden (2000) was a turning point. The co-director, Damien Louche-Pélissier, fought with the studio to get it made, as it was hard to get Folimage’s new generation to handle the reins.

Chieux points out that Spud, similarly to the American Snoopy or the Japanese Shin-chan, is quite an interesting design, as he’s a purely 2D character. You can’t really imagine him in 3D, it’s purely drawings. In a sense, Spud’s team was emulating John Hubley’s UPA work, such as Gerald McBoing-Boing. Chieux is still bittersweet about Spud and the Vegetable Garden : he enjoys the final product, but remembers it as a troubled production. Rising tension with the studio leads and his own immaturity at the time sadly made him scrap his next project, Gus & Sylvia. Thankfully, this was a relatively unique incident in Chieux’s career, as most of his other ideas ended up being made.

Some years later, Chieux began working on Mia and the Migoo, which would be released in 2008. Chieux can’t deny Miyazaki’s influence slowly creeping in his own productions, and took some time explaining how the legendary director’s work came to his attention. A friend of his took a trip to Asia and bought a random assortment of animated films on VHS tapes, without knowing anything about what might be contained inside. Picking a movie at random, the two friends put on The Castle in the Sky. At the time, Miyazaki was still completely unknown in France. Even though bootleg Thai subtitles occupied most of the screen space, Chieux quickly realized that he was watching something truly special, and showed the movie to his own children. One big difference he noted was that unlike in Disney films, you aren’t only watching the action, the camera is inserted straight in the heat of it. As he wasn’t able to buy more at the time, he remembers watching this tape collection over and over for inspiration.

In Mia and the Migoo and his following movie Tante Hilda !, Chieux was alone at the helm for the storyboarding phase. Drawing, and most especially direction, was at the heart of his work at the time, as he was tired of how technical the industry had become. Too many computers!

This technical fatigue was the driving force behind Chieux writing academic papers about the importance of simplicity in 2D animation. Being a teacher himself, he also had the chance to participate in symposiums about limited animation. Tante Hilda ! was made that way, and even went the extra mile: animators were forbidden to erase any construction lines! Chieux recognizes how hard an undertaking it was, but results paid off, as the entire team progressed immensely. It was also a great way to showcase how alive a drawing could truly be.

In 2015, Chieux also worked on some short films. It wasn’t really planned or something he really wanted, but in his mind, it was a way to cope with his growing impostor syndrome. These smaller works help him to keep his mind in the game. It’s daunting to work at the helm of big productions all the time. Scaling back is pleasant sometimes. On top of it, his first short film, Tigers tied up in one rope, was adapted from a book, making the distance even bigger. Of course, short films are also a great way to experiment, without having to commit to a single artstyle for years. Each of Chieux’s shorts were produced in 4 months only. In a way, it’s very pleasurable, and much less stressful.

Chieux always wants to switch up the entire artstyle for each of his productions. The visual work is a vital part of a film, so for him, staying in the same one would feel like betraying that. He also notes that sometimes, a project defines its look, not the other way around. The short Coeur Fondant has a lot of hairy imagery, so it was decided pretty early on that it was going to be all about volume. Chieux first imagined it as 2D animation, but was quickly convinced to switch it to stop-motion.

Around this time, Chieux met Titouan Bordeau, an up-and-coming animator, at La Poudrière, an animation school. Bordeau went on to work with Chieux on all his short films. The two animators bonded very quickly. Bordeau is very skilled, and always strives to imagine new universes, much like Chieux. When working together, they’re able to bounce rich ideas off of each other. It’s an ideal mentor-mentee situation, as Chieux is able to learn a lot from working with talented young people as well.

One of the two men’s closest collaborations was the short Coralie et les escargots, released in 2021. Work on Sirocco had of course already started, but Bordeau invited Chieux just as he was finishing his storyboard. In 3 days of brainstorming, they had everything they needed, from the subject to the slow animation style. The audio comes from a documentary by French public radio channel France Culture, and they quickly got authorization to use it. Bordeau would animate, and Chieux would draw the backgrounds. 14 minutes was more of an undertaking than they’d first thought, so they started working with a self-imposed restriction: as few shots as possible. Time was of the essence, so Bordeau’s storyboard ended up being very sketchy. The sketchiness was so intense that Chieux couldn’t really tell what he was supposed to draw half of the time, but Bordeau went on to animate on these experimental backgrounds. This erratic process is what gave the short its unique aura. The film was produced in only 2 months, without any cash flow. Chieux notes that if they’d made any money with it, it would’ve been sent to the mom who narrates the movie.

After discussing his recent shorts, Chieux finally got into the genesis of Sirocco, showing many sketches along the way. The very first drawings date from 2012, and aren’t roughs but already completely finished drawings. It’s almost as if they came from an existing movie, but without any scenario idea behind it. Chieux precises this is how he proceeded, even though it’s an unusual way of doing things.

The director showed the starting point of the film, in which we can already see the two main characters – two sisters – taken away by a tower mill. The emphasis on the wind and the large spaces was already there. The flying crocodile too, that remains in the final movie, is also in those first visuals. One of Chieux’s first inspirations was Paul Driessen: he loves his drawings, how he animates, his mix of childish aesthetic but serious themes in his work, and how he thinks of children as grown ups.

During the early stages, Chieux had the idea of making creatures that were just cut hands. When he presented these sketches at Cartoon Movie in 2014, he met Jérémie Clapin, who was presenting his own film, I Lost My Body. When Clapin saw the teaser Chieux and his team made, he got kind of disgusted and told Chieux “I’ve been working on my project for 10 years and you come up with your new stuff, which turns out to be the same thing…” This wasn’t helped by the fact that Cartoon Movie got the “wonderful idea” to show both trailers one after the other. In the end, Chieux decided to remove the hands from his own project. It wasn’t just Chieux being nice to Clapin: seeing that someone had had the same idea, he simply lost interest in it, even though he still thinks it was a great idea, visually strong and bringing a strange atmosphere. But he was told that cut hands weren’t really appropriate for children.

After that, Chieux worked with two writers on a scenario from these drawings. But it didn’t really work out well, and he was unhappy about what they wrote. The project didn’t move on for three years, but he met up with Ron Dyens, the producer of Sirocco at studio Sacrebleu Productions. It was during that time, when Dyens was looking for staff and money, that Chieux produced his aforementioned shorts. Finally, the script was left in the hands of Alain Gagnol, also a former alumnus of Émile Cohl school and a member of studio Folimage, and now an important director in the French animation landscape.

At first, Chieux wasn’t really excited about working with Gagnol because he wasn’t really sure about the alchemy: Gagnol had previously worked mostly on adult crime stories. How was he supposed to fit in a movie featuring, among other ideas, giant ducks? But they made a test, and it turned out very well. Gagnol was fully able to make the movie his thing. The only challenge was that, at first, Gagnol only wrote about characters inside houses, talking. It was Chieux who told him characters had to go out and experience adventures.

Gagnol understood very well and thought of the drawings Chieux made as puzzle pieces: his script was just adding the missing ones to make the overall picture complete. Chieux had begun sketches in 2012, and Gagnol only joined in 2018; but things accelerated and, in September 2021, the rush period finally started as the production began in earnest. It’s one of the paradoxes of animation production noted by Chieux: you have to wait almost a decade for things to begin, and once they do, everything goes very fast. The actual production only lasted 18 months, which is quite short for such an ambitious movie.

The long buildup to Sirocco’s release can be explained by Chieux’s work on his short films.. Le Jardin de Minuit was particularly important because Chieux wanted to make this movie the opposite of the usual way. Instead of starting with a scenario and a strong idea, he wanted to show chaos and deconstruction. It’s important in a story to have elements existing only for themselves: if everything has a meaning for the story, as a spectator you feel like you’re being guided through the story. It makes the universe way more real and it creates stimulus in everyone’s brains. Those elements, for example the lighthouse in Sirocco, can be scenarios on their own too, but it’s not necessary.

A friend of Chieux told him there are two kinds of scenarios. The “centrifugal” one, in which the action rotates around the starting point, and leads to the conclusion, and the “centripetal” ones, starting from a point and as the movies goes on, you move away from this starting point, just as in The Boy and the Heron for example. This kind of scenario has no end, it could last indefinitely. What makes it interesting is that the stimulation isn’t just logical.

Chieux loves to make storyboard, and Sirocco’s was particularly interesting, as it deals with large spaces and the discovery of a new world. The landscapes become a main character, and depicting them is very stimulating. Chieux had to fill the universe with details, such as architecture, morphology, how characters move etc… He drew a massive amount of them directly on paper, without sketching. The goal was to make characters alive, without thinking about camera work at first.

Tante Hilda, the feature on which Chieux had previously worked, was a very talkative movie, which entailed a lot of restrictions for the directing, which frustrated Chieux, who decided to restrain the dialogues. Sirocco’s scenario ended up being 60 pages long, which is rather short for a full length movie. So it left room for the “useless” shots, but very important for the universe.

Coming back to his sketches, Chieux talked about houses. He drew some fantasy ones just to imagine how he could destroy them. Another example is the beginning of the movie, set in a normal house. Chieux had to draw the house layout to make it real, but later got many corrections from his wife, a professional architect. The director was very peculiar about this opening scene, as he thinks that the beginning of a film is quite important: it settles the energy, the tempo, the universe. It’s really important to catch the spectator’s attention really fast.

Then, Chieux showed the animatic for the opening scene, which he made himself. It’s extremely detailed, and the director once again emphasized how he wanted to create a sense of space and realism. He went as far as using real-life reference for the shot of the two girls’ mother getting into her car, borrowing the help of a completely unknown old man from the neighborhood…

Such things weren’t the only issues Chieux and the animators faced. Among those was designs: the characters have patterns on their clothes, which makes them more interesting to look at but much more difficult to animate. For instance, if the number of stripes on a character’s clothes changes, it’s immediately visible. However, it’s worth facing such a challenge, because it’s one that animators and designers rarely want to face and it allows for beautiful pictures.

Effects animation was also very important for the movie, and they had the opportunity to work with Jonathan Djob Nkondo, one of the most famous and respected animators in France (he was recently the director of Scavenger’s Reign). Indeed, Chieux noted that he’s one of the few artists in the country who has the liberty to choose what projects he’ll work on. This time, it was exceptional as Nkondo was the one who approached Chieux rather than the opposite. This talented animator was in charge of part of the climax, when the tempest wakes up and destroys the building Sirocco built to seal it.

Another concern was color, because there are no shadows in the film. The whole image had to be filled up with color. It was a challenge but it became a game of “how many colors can I put in this shot”. Only three people total ended up working on the movie’s backgrounds. The Production Designer called Alex Rimbault made around 200 key backgrounds, and the remaining 1000 were almost all made by Julia Petrov and her assistant. They are quite simple but had to be very clear and attractive. Making things simple is actually the most difficult, as you have to be perfect. Chieux took the example of Tintin: if you misplace an eye even by a little bit, it’ll look very odd and be instantly noticeable.

After this long talk, which lasted well over an hour and a half, Chieux answered questions from the audience.

When asked about inspirations – the question that comes up the most about the film – Chieux stated that there aren’t any clearly defined ones. As explained earlier, Sirocco started as a series of drawings and everything was very organic, changing as time went by. Chieux summed it up by saying he never thought he wanted to “make it like this or that”. Similarly, when asked, Chieux said that the movie wasn’t inspired by his dreams or anything like that. However, he said that he hopes viewers won’t be able to tell if the movie is a dream or a nightmare: he wants to create that impression when you wake up after a dream and you’re not very sure about what kind of dream it was. For example, characters can be frightening, but they always show joyful colors. But the risk of it is to “create too much”. Gagnol warned Chieux about that, and if there was one clear inspiration, it would have to be Alice in Wonderland, because the narrative structure is the same. You have to put the spectator at ease before showing him the whole unbridled universe. Chieux’s conclusion was that your universe mustn’t overtake the story and the emotions.

The issue of shadows came up again, as someone asked whether it was also influenced by Japanese animation. Chieux denied the inspiration here, claiming it was both a budget issue and a challenge he wanted to put on himself. Regarding Japan, Chieux said that he took a different approach, as he wanted to make a crossover between the European design sense and the Japanese style approach to direction.

As a final piece of advice for young creators who are not sure about how to start their project, Chieux said that you have to listen to your heart. He’s got huge respect for artisans and skilled technicians whose only goal is to make a living, and acknowledges that not everybody wants to make their own movies. Most of his time at Folimage was very similar, and he had to take care of his family. In other words, one musn’t be ashamed about that: what’s important is following the path that suits you best. However, if you want to create, you have to dare and to believe in your projects. Taking opportunities, knocking at every door, even if it doesn’t always work out well.

As a final word, Chieux confirms that the most important part for him is direction, because it’s through the direction that style is expressed. It’s by directing that the director exists, film is a language. Just like poetry, it’s not just about thoughts or feelings, it’s about choice and use of words to express those thoughts.

Translation and summary by Florian Abbas, Loïc André, and Matteo Watzky.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Directing Mushishi and other spiraling stories – Hiroshi Nagahama and Uki Satake [Panels at Japan Expo Orléans 2023]

Last October, director Hiroshi Nagahama (Mushishi, The Reflection) and voice actress Uki Satake (QT in Space Dandy) were invited to Japan Expo Orléans, an event of a much smaller scale than the main event they organized in Paris. I was offered to host two of his...

Akira stories – Katsuhiro Otomo and Hiroyuki Kitakubo talk at Niigata International Animation Film Festival 2023

Among the many events taking place during the first Niigata International Animation Film Festival was a Katsuhiro Otomo retrospective, held to celebrate the 45th anniversary of Akira and to accompany the release of Otomo’s Complete Works. All of Otomo’s animated...

fullfrontal.moe 2023 wrap up and plans for 2024

As we enter this new year, I have grown accustomed to taking a look back at the past year to give you an idea of fullfrontal.moe's situation, what we were able to achieve together with your support and fidelity, and share our prospects for 2024. But before getting...

Recent Comments