Understanding of the Japanese animation industry has developed a lot in English-speaking circles. However, while in-depth records or detailed anecdotes about specific productions have become easier to find, a general overview of the industry as a whole is still missing. This series doesn’t aim to provide something half as ambitious, but hopes to provide some of the resources necessary to advance in that direction.

The goal of this series, then, is to offer a quantitative perspective on the anime industry, sharing some of the numbers and data that are available in Japanese, but not in English. Numbers are not absolute, and neither are they the key to a final, “objective” approach of the anime industry. But they can help us obtain a distance and perspective that the usual, qualitative approach does not, or rarely, have. Each entry in this series will therefore use different sources, on a variety of topics related to the anime industry, in the hopes of clarifying and improving our overall knowledge of it.

The first entry in this series, dedicated to the overall number of anime being made, is available here.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

Last time, I ended on the conclusion that just the raw number of anime being made, or even how many minutes of animation are produced, aren’t enough to provide a real perspective on the situation of the Japanese animation industry. Alongside other factors such as general profit and growth, it may give us an idea of the overall development of the industry and of the way business is heading as a whole, but it’s not very insightful on the way things actually go on the side of production.

To start discussing this issue, I will therefore provide some data on anime studios; next time will be dedicated to the animation production staff themselves. The numbers are taken from two sources: an August 2022 survey conducted by the company Teikoku Data Bank, supplemented by a 2019 survey conducted by the Association of Japanese Animation Creators (JANICA).

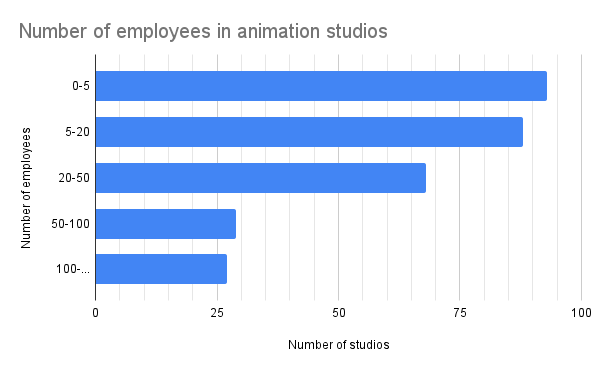

First, let us start by a basic question: how many animation studios are there? Teikoku’s survey notes 309 studios overall, from major production companies to smaller, specialized outsourcing studios. Unsurprisingly, the majority (276) are located in Tokyo. The sample is much smaller, but the JANICA survey also showcases Tokyo-centrism, as 76.2% of the respondents reported living in Tokyo, and another 12.3% in Kantô, around the capital.

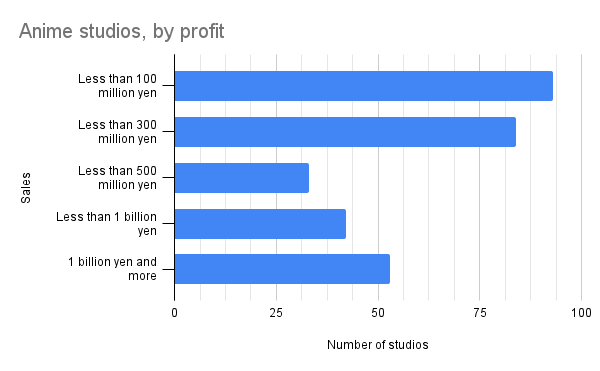

As the charts below shows, most animation studios are very small, either in profits or number of employees. These numbers aren’t surprising, as this structure has been characteristic of the anime industry since the very beginning. What is perhaps more surprising, however, is how recent most studios are – 200 have been created after the year 2000. While it is hard to tell without more data spread over time, this could indicate two possible, non-contradictory, phenomena:

1) The anime industry is dynamic, leading more people to join and create companies

2) The anime industry is unstable and the lifespan of an animation studio is very short, causing most older companies to have disappeared

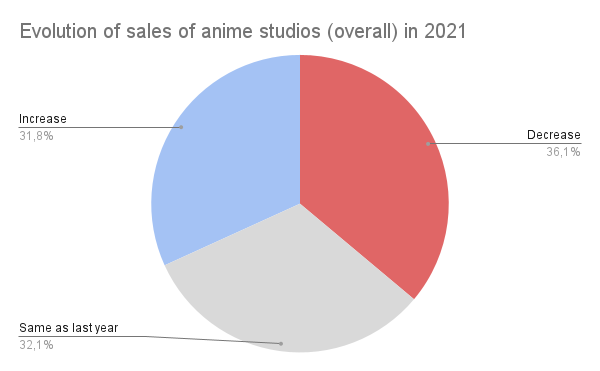

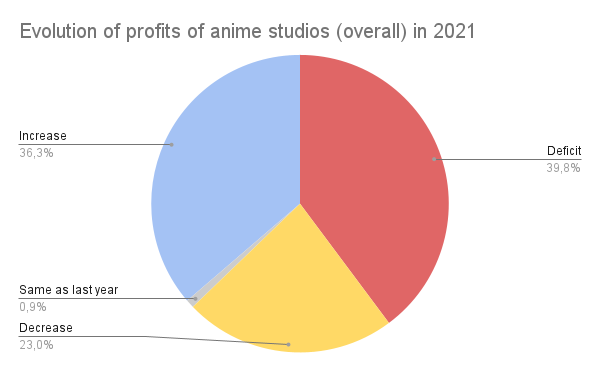

With these general numbers in mind, we can turn towards more interesting data: the commercial performances of anime studios. With these numbers, it is possible to get a better view of the overall state of the industry and whether those that support it are actually doing so on a sustainable basis. And the answer here is clear: the anime industry is not sustainable. Admittedly, it never has been – but this doesn’t make the situation less worrying. Between 2019 and 2021, the overall profits of the anime market have decreased, a downward trend generally attributed to the pandemic. But, given the fragility of most studios, the results are more visible on the small level than for the overall industry.

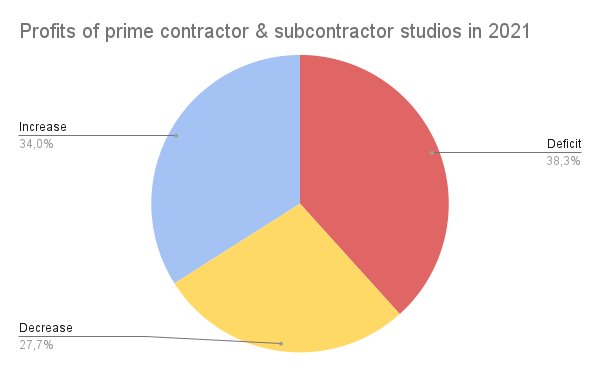

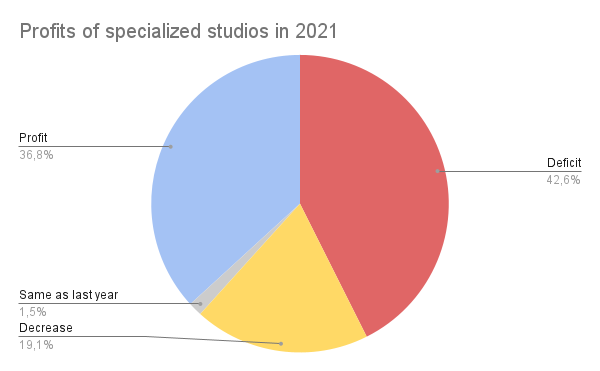

As the chart below shows, in terms of sales, the situation is already not looking good – a bit more than a third of studios have seen their sales decrease. But the real problem lies in the actual profits: almost 40% of overall studios are in the red (a record high), while another 23% have seen their profits actually decrease.

The numbers become even more worrying when we separate between different types of studios as below: on the left are the prime contractors and subcontractors, that is studios able to handle all or most of the pipeline, and on the right “specialized” studios, which only handle one task of the pipeline, such as in-betweening, coloring or photography. While that’s still not reassuring, the numbers are relatively balanced among prime contractors and subcontractors, while an overwhelming majority of specialized studios are in a precarious situation. As already mentioned, anime studios have always been in financially difficult spots, but the numbers on display here seem to be some of the worst ever recorded. Notably, it is the second year in a row that more than 40% of specialized studios are in deficit, the first time this has ever happened.

On a short-term basis, the pandemic once again seems to be the one to blame. The decrease in the number of productions means a decrease in revenue (even though it might mean less work, and better conditions for individuals), while specialty studios constantly have to bear the costs of upgrading their equipment.

The decrease in the number of overall productions creates a vicious cycle for studios: less productions means less revenue, which in turn decreases each studio’s ability to update their tools and increase their staff, and ultimately to increase their revenue. As is often discussed, some studios try to escape this vicious cycle through brute force, taking in more orders than they can actually manage. But this doesn’t really improve things for multiple reasons:

- It makes working conditions harder for the base staff, decreasing their overall efficiency and accentuates the competition between studios

- In the end, it doesn’t solve the problem, because new staff has to be recruited to solve the overwork issue, meaning that the studio will have more people to pay and make less money, restarting the cycle all over again

- It ultimately rests on the premise that there is more staff to recruit in the first place

For these reasons, while the decrease in the number of productions is a source of problems, a rise in that number isn’t really a good solution either. The main issue is therefore twofold: the management of studios, and ways to ensure that studios can actually make profit on a sustainable basis.

A more enduring trend, that was only accelerated by the pandemic, seems to be the widening of the gap between “major” and “minor” studios. Major studios are those who have a large workforce, stable subcontracting networks, and most notably hold at least some of the rights to their IPs. Thanks to this, they are able to keep productions going and to profit from their works even when they’re shown on streaming services. A spectacular case of this has been the IG Port conglomerate, and most notably studio WIT, which seems to have tremendously profited from the success of Ousama Ranking and, more notably, Spy X Family.

Here, it is time to enter more speculative territory, as this trend may be bound to suddenly accelerate because of another factor: the reform of the Japanese consumption tax, also known as the “invoice” law, which should come into effect in October 2023. Put simply, the system through which companies will fill out invoices to be exempted from consumption tax will become more complex and make a clear separation between companies’ profits and those of freelancers working with them. This will make administrative work more difficult to handle, but that is not all. As a result, freelancers earning under a certain level will have to pay more taxes (up to 10% of their income), or the studios will have to shoulder that cost, making it very disadvantageous for them to employ freelancers. As we will see in the next piece, the vast majority of animation workers in Japan are freelance – not just animators, but also actors and many other positions all along the pipeline. This could mean that, by a few years, many freelancers may quit and small studios unable to bear the costs will close down, while the bigger ones making more profit and having more in-house staff will be less affected.

In the next piece of Anime Numbers we will focus on anime staff themselves and their “working conditions”. It will cover topics such as salaries, working hours, and their evolution through time.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Benoît Chieux, a career in French animation [Carrefour du Cinéma d’Animation 2023]

Aside from the world-famous Annecy Festival, many smaller animation-related events take place in France over the years. One of the most interesting ones is the Carrefour du Cinéma d’Animation (Crossroads of Animation Film), held in Paris in late November. In 2023,...

Directing Mushishi and other spiraling stories – Hiroshi Nagahama and Uki Satake [Panels at Japan Expo Orléans 2023]

Last October, director Hiroshi Nagahama (Mushishi, The Reflection) and voice actress Uki Satake (QT in Space Dandy) were invited to Japan Expo Orléans, an event of a much smaller scale than the main event they organized in Paris. I was offered to host two of his...

Akira stories – Katsuhiro Otomo and Hiroyuki Kitakubo talk at Niigata International Animation Film Festival 2023

Among the many events taking place during the first Niigata International Animation Film Festival was a Katsuhiro Otomo retrospective, held to celebrate the 45th anniversary of Akira and to accompany the release of Otomo’s Complete Works. All of Otomo’s animated...

Hi, love your work here! These articles are so helpful to understand, even a bit more, the complex situation which the anime industry is in right now.

I have a question about the Japanese Consumption Tax and what it means to freelance animators, or even just freelance workers, actually. I can’t read Japanese, so my research was not very helpful and I hoped that you could help me figure out what’s going on.

When you say “As a result, freelancers earning under a certain level will have to pay more taxes”, do you know the regulations or the cause of this situation? From a logical point of view, it doesn’t seem right at all that people who earn less should pay more. Or maybe it’s just me and I’m missing something from the big picture.

Thanks for your comment!

Actually I don’t fully get it myself because even though I read Japanese somewhat, all this tax and legislation stuff goes a bit over my head – which is why what I’m saying here about the invoice law is sadly very general. I really wish someone with more specified knowledge could report about this in more detail because it’s a really big thing.

To answer your question to the degree I can, I believe the government’s argument is mostly related to taxing “equally” (as in, no exceptions made) and generally having to find ways to get some money in. But there might be more to it, and I agree with you that it doesn’t sound very right presented like this.