Understanding of the Japanese animation industry has developed a lot in English-speaking circles. However, while in-depth records or detailed anecdotes about specific productions have become easier to find, a general overview of the industry as a whole is still missing. This series doesn’t aim to provide something half as ambitious, but hopes to provide some of the resources necessary to advance in that direction.

The goal of this series, then, is to offer a quantitative perspective on the anime industry, sharing some of the numbers and data that are available in Japanese, but not in English. Numbers are not absolute, and neither are they the key to a final, “objective” approach of the anime industry. But they can help us obtain a distance and perspective that the usual, qualitative approach does not, or rarely, have. Each entry in this series will therefore use different sources, on a variety of topics related to the anime industry, in the hopes of clarifying and improving our overall knowledge of it.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

Let us begin this series by one of the most discussed issues surrounding the anime industry – that of the number of anime being made. As people are repeatedly evoking the fact that the Japanese industry is facing a surproduction crisis, the most natural answer is to go look for the raw number of animated productions being made. This isn’t entirely satisfactory, as we will see later on, but it is still a good indicator of where the industry is at the moment. However, there is one important note to make: it may be difficult to draw definite conclusions from the last 3 years – 2020, 2021 and 2022. Indeed, because of the pandemic, many productions were delayed to another season or year, causing irregularities in pipelines.

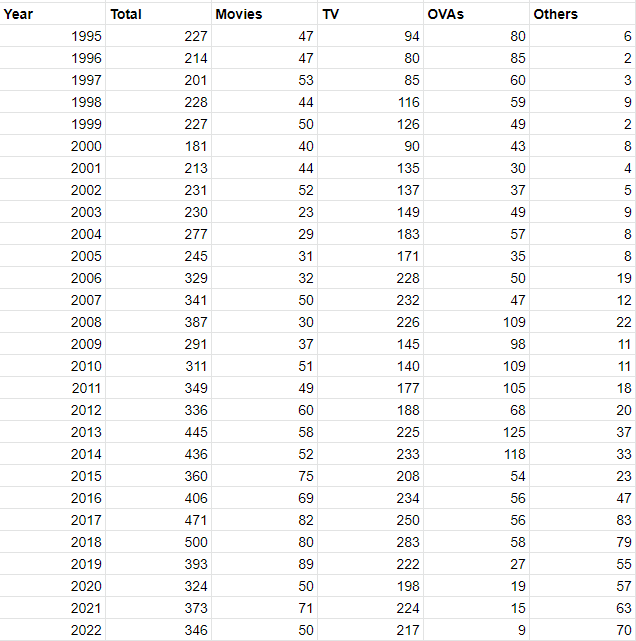

There have been multiple ways to count the number of productions, most of the time with a special focus on TV: the number of shows being aired, or of episodes, or of minutes. Because of this centrality of TV, it doesn’t give a grasp of the industry in its entirety. So, to begin, I’m going to take the overall number of productions, regardless of format; the numbers are taken from the Japanese AnimeDatabase.

The general trend over the history of Japanese animation has been a rise in the number of productions. Here, just starting from the 1990s, we notice this trend, with few lasting slumps. More specifically, there have been 3 peaks: 2008 (387 works), 2013 (445) and 2018 (500). There has been a strong decrease since then, and even allowing for the disruptions caused by the pandemic, it seems like the situation is roughly back to what it was in the 2000s. Whether it’ll spike up again remains to be seen.

The number of new anime productions per year, 1995-2022 (from Japanese Animation Database “Anime TAIZEN”(https://animedb.jp/))

(Other surveys with different criteria exist and provide slightly different numbers than the Japanese AnimeDatabase. However, regardless of the exact numbers, the trends are the same: see this survey made by a Reddit user in 2020, which reaches a similar conclusion for TV series – a peak in 2018 followed by a decrease in 2019 and 2020. Same for the number of movies, as can be seen here.)

However, to better understand these numbers, it is necessary to break them down by format. Focusing on 2018, we can see that the high number of TV shows fell within a longer trend, but that the high number of productions in other formats was more exceptional for various reasons:

1) Following the release and unexpected success of Your Name, the number of feature films in the years 2017-2019 was at an all-time high

2) Web formats and releases (classified under “others” here) were on the rise, and had already peaked in 2017

3) 2018 is probably the last year in which the OVA format had any kind of visible presence, as the number of OVA releases plummeted in the following years and is now under 10

It is interesting to compare this situation to the one of the 2020s. I of course can’t speak for future evolutions, but the number of feature films, expected to rise substantially following the success of Demon Slayer: Infinity Train, hasn’t gone through that much growth between 2020 and 2022 as it has following Your Name. There was indeed a sudden increase in 2021, but it was probably largely the result of all the movies delayed in 2020 being pushed back to the following year. On a short-term basis, then, it is possible to say that the number of theatrical works has been declining rather than rising.

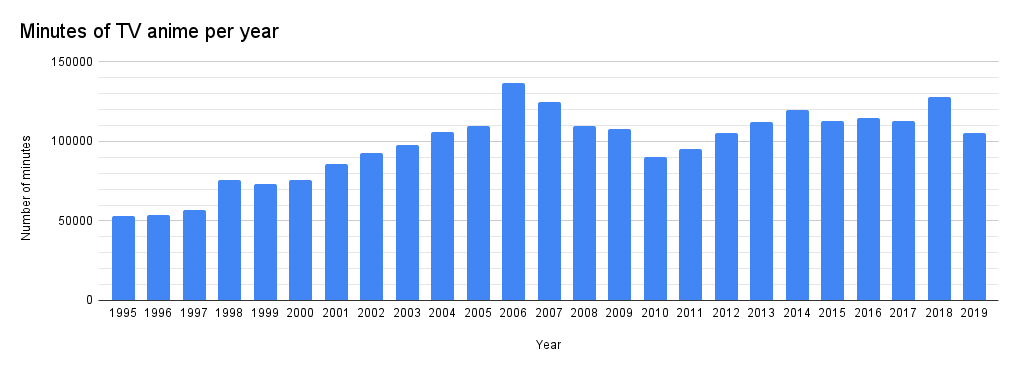

This first set of numbers is valuable because it provides an overall look on all formats. But if we focus on TV, we risk the confusion between the number of new titles and what’s actually aired: long-running shows, which go on for multiple years, necessarily disappear if we count the number of new productions per year. This is why a more representative metric would be the number of episodes aired each year or, even better, the number of minutes. The following graph, compiled by Hiromichi Masuda in 2021, provides that latter number.

The number of minutes of animation aired on TV per year, 1995-2019. Cited in Nagata, Daisuke & Matsunaga, Shintarô (2022). A sociology of industrial change: history of animators’ experiences (産業変動の労働社会学 – アニメーターの経験史). 晃洋書房

This new set of data helps us put the previous one in perspective: while it may seem that 2008 represented a peak because of the amount of new works, it would actually have been 2006, which saw around 20,000 minutes more of animation air on TV. Actually, 2006’s record has not been beaten, even in 2018, which witnessed almost 50 more TV shows on air. The general shift from 2-cour to 1-cour shows may have inflated the overall numbers, but not the actual amount of content being aired.

Once again, this data set only provides information for TV works, and the numbers only go up to 2019. However, the sharp decline in number of minutes between 2018 and 2019 naturally coincides with that in the number of productions. Considering that this latter number has (irregularly) declined in the past 3 years, it is not unreasonable to conclude that, even if we count the number of minutes, less TV anime is being made than before.

Does that mean, however, that “overproduction” is not an actual issue? The answers to this are more complex; I’ll outline them quickly as a conclusion here, and get into the details of some later on.

1) What matters is less the number of productions than the number of people. If the industry had enough people to make a thousand TV shows per year, then there’d be no problem; but the question is whether it actually does.

2) Anime production takes time. It’s usually said that the overall time to make a TV series, from the initial planning stage to the actual broadcast, is around 2-3 years. In other words, it’s not just about how many works come out each year, but about how many are in production at the same time – bringing us to another, non-quantitative, issue.

3) It’s not just a question of numbers. More minutes of animation does entail more time spent drawing and working for animators and other staff, but the more general issue is one of schedules. And, with one-cour shows, schedules have to be restarted all over again twice as many times as with two-cour shows, making management far more complex. If all productions are made at the same time by the same people, their actual number is secondary – the situation will lead to general burnout in a way or another.

In the next piece of Anime Numbers we will go through data about anime studios. How many there are, how much staff they employ, and their sales and profits.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Benoît Chieux, a career in French animation [Carrefour du Cinéma d’Animation 2023]

Aside from the world-famous Annecy Festival, many smaller animation-related events take place in France over the years. One of the most interesting ones is the Carrefour du Cinéma d’Animation (Crossroads of Animation Film), held in Paris in late November. In 2023,...

Directing Mushishi and other spiraling stories – Hiroshi Nagahama and Uki Satake [Panels at Japan Expo Orléans 2023]

Last October, director Hiroshi Nagahama (Mushishi, The Reflection) and voice actress Uki Satake (QT in Space Dandy) were invited to Japan Expo Orléans, an event of a much smaller scale than the main event they organized in Paris. I was offered to host two of his...

Akira stories – Katsuhiro Otomo and Hiroyuki Kitakubo talk at Niigata International Animation Film Festival 2023

Among the many events taking place during the first Niigata International Animation Film Festival was a Katsuhiro Otomo retrospective, held to celebrate the 45th anniversary of Akira and to accompany the release of Otomo’s Complete Works. All of Otomo’s animated...

“with one-cour shows, schedules have to be restarted all over again twice as many times as with two-cour shows” I don’t understand this statement so well. Can someone explain please?

Hello, thank you for your comment. I will try to clarify the statement as best as possible.

A cour (from the japanese クール [kuuru], loanwoard from the French word cours) is a thirteen week period during which a TV show gets aired. It is the correct terminology for what commonly get erroneously called in English a «season». A one-cour show as such is one with 13 episodes that get aired, and a two-cour show is one with 26 consecutive episodes that get aired. So take the example of a long running show that takes a break between each of its cours, like Chainsawman or Musshoku Tensei currently, compaired to a show that has multiple consecutive cours, like Fullmetal Alchemist. The shows consisting of multiple one-cours series need to rework their schedule, preproduction materials and staff for every new cours, whereas a show running multiple consecutive cours only has to go through all these steps once. The one-cours shows might have the advantage of taking less risk at a time, but end up using up more resources in the long run than a multiple cours series.

I hope this helped, please let me know if it wasn’t clear enough.

thanks a lot

Sorry, my formulation wasn’t very clear. What I meant was:

With long-running shows, as long as things are well planned and there aren’t any major problems, you can more-or-less let the rotation run in automatic mode and prepare for things in advance.

With short shows, everything is on the short-term, and so faster and more stressful. Moreover, you have to make twice as many pre-production preparations – that is planning, budgeting, selling, designing, writing a show – which means more and different work on the production staff.

Really appreciate your help, I can get the hang of it now