This article wouldn’t have been possible without the direct or indirect help of all the people sharing anime-related resources, scans, photos, translations and transcripts on the Internet. All my thanks go to Harley and Dylan Acres from Rumic World, ehoba, Rick, Animarchive, Mio Fukamachi and all the others.

This article is released for a special occasion: the beginning of a new animated adaptation of Rumiko Takahashi’s Urusei Yatsura produced to celebrate the 100th anniversary of publisher Shogakukan. Whatever the purpose and quality of this new series, it raises one obvious question: will it live up to its predecessor? And will it, in any way, create an impact equal to the one the original manga and anime had in 1980s Japanese pop culture?

While it is not my intent here to speak ill of the new anime – especially since I have seen nothing of it as I’m writing these lines – my answer to the above questions is a definitive “no.” The reason for that is simple: beyond their innate, one might say timeless, artistic qualities, the original Urusei Yatsura manga, and anime are heavily dependent on their production and reception contexts. Without this context, any new Urusei Yatsura media is bound to be fundamentally different; it remains to be seen whether the series will fit in the 2020s as well as it did in the 1980s.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

It should be noted, however, that Urusei Yatsura’s “context” is not so simple to pin down. Rumiko Takahashi’s manga ran for almost ten years between 1978 and 1987, while the TV series aired from 1981 to 1986 and was followed by multiple movies and OVAs until the early 1990s. Each new entry – the manga, the TV anime, the movies, the OVAs, and all the video games, tie-in products, and fan productions – should be understood according to its own principles and situation. This is what this article will endeavor to do, by avoiding blending all Urusei Yatsura media under the image of a singular “franchise” and rather by trying to depict it as both a complex network of interrelated media and a cultural phenomenon – or rather, a series of cultural phenomena.

Rumiko Takahashi, the roots and evolutions of Urusei Yatsura

At the crossroads of gekiga and gag manga

Urusei Yatsura’s story naturally begins with its creator, mangaka Rumiko Takahashi. Born in 1957, Takahashi’s distinguishing quality was being well-read. From a young age, she read the manga magazines bought by her brothers or available in her parents’ medical practice. She would unsurprisingly start by classic children’s manga such as Obake no Q-Tarô or Osomatsu-kun, but soon moved on to more mature, experimental publications: she was an avid reader of both Garo and COM, the two leading arthouse manga magazines of the late 60s.

Takahashi did not just read, she also drew, and drew, and drew. By junior high, she was already submitting 4-panel strips to her favorite magazines, Garo and Shônen Sunday, and soon created a manga research group with classmates. There, she discovered yet more artists, reading Tetsuya Chiba or coming into contact with Moto Hagio and becoming a shôjo manga fanatic, while still submitting stories to magazines. It was probably at this point that Takahashi’s resolve to go pro solidified: when she entered university in 1975, she also joined a manga school, Kazuo Koike’s Gekiga Sonjuku. Koike was the writer of dark, violent manga one would not immediately associate with Takahashi’s sensibility such as Lone Wolf and Cub, Lady Snowblood or Crying Freeman. But the fact that he was her mentor only illustrates Takahashi’s range of influences and interests. It was him who encouraged her to self-publish her first creations and gave her essential lessons in storytelling, including one which Takahashi would keep citing as the core of her work: to always put the characters in the center and to have them drive the action.

It was at this time, somewhere between 1975 and 1978, that what would become Urusei Yatsura was created. Among the story outlines Takahashi wrote under Koike’s teaching, there was one involving a busty, sexy, scantily clad alien girl inspired by popular Chinese-Hawaiian singer and model Agnes Lum – she would be the prototype for Lum Invader.

Things slowly began to progress as the young Takahashi kept publishing doujinshi and applying to magazines’ contests: at some point, an editor from Shogakukan, who clearly recognized her talent but was unable to give her any work, sent her to become the horror manga legend Kazuo Umezz’s assistant for a few days. And then, success finally came: in 1978, her story Kattena Yatsura – also known as These Selfish Aliens – won an honorable mention at Shogakukan’s New Comics Contest. Kattena Yatsura was a 32-page long, convoluted alien-abduction story full of pop culture and folklore references, and its dark humor was directly taken from Japanese SF novelist Yasutaka Tsutsui. When Takahashi was asked for a follow-up to the short, she kept the same ideas and tone. As if to highlight the continuity, her editor decided on a similar title: an even more elaborate (and impossible to translate) pun, Urusei Yatsura.

At that point, Takahashi was still a 21-year-old university student, and Urusei Yatsura‘s serialization was initially made in batches she wrote during her holidays: the first five chapters were written during the spring holidays and published between August and September 1978; the next ten were written over the summer and came out from November 1978 to April 1979. Publishing continued irregularly until chapter 18, in October 1979, as Takahashi started work on a second series, Dust Spot. But Urusei Yatsura was the most popular of the two, and, starting from chapter 19, published on April 18th, 1979, it would come out weekly in the pages of Weekly Shônen Sunday.

The artistic evolution of the Urusei Yatsura manga does not quite follow its complicated publication history. Indeed, it is possible to note a difference between the first ten chapters, which follow in Kattena Yatsura‘s wake, and those that came after, in which the series took radically new directions. In a way, one could say that at first, Urusei Yatsura still belonged to the 1970s, but then moved on and truly opened what would become 1980s manga.

The early phase is often characterized by what critics call its “dry humor”: a sort of ironic distance and detachment from the events and misfortunes of the characters. This tone partly came from Tsutsui’s influence, but that was not all: the early chapters indicate Takahashi’s range of references, from horror manga to romantic shôjo and science-fiction. Lum’s appearance in the first chapter established Urusei Yatsura as SF. Still, Takahashi initially conceived it as belonging to a highly conventional genre: “neighborhood comedy,” initially centered on the misfortunes of Ataru and focused on the triangle he formed with his girlfriend, Shinobu, and the doom-monger priest Cherry. At this stage, Lum was simply supposed to be a secondary character appearing from nowhere to endanger Ataru and Shinobu’s relationship. If the tone was “dry,” the stories were absurd and over-the-top: this combination had been initiated in the mid-70s by Tatsuhiko Yamagami’s Gaki Deka, a dark, violent, and sexual comedy series following the misadventures of local policeman Komawari-kun. Considering Takahashi’s range, Yamagami’s work was perhaps the most appropriate influence for Urusei Yatsura: he was the first mangaka to combine the graphic dimension of gekiga with the absurdity of gag manga. Takahashi initially stood at the very same crossroad, but she quickly matured as the manga advanced, her art evolved, and her involvement increased: after a few chapters, Urusei Yatsura would start opening completely new options for comedy manga.

“Manga’s back in Shônen Sunday”

In the highly-competitive field of weekly manga publications, artists need to have one important quality: discerning what the audience wants and adapting themselves to it. Perhaps tipped off by her editor Makoto Oshima, Takahashi quickly noticed what was Urusei Yatsura’s appeal: Lum Invader. What was initially meant to be just one of multiple recurring secondary characters soon became the manga’s cover girl. At the same time, Takahashi’s technique quickly evolved: the initial chapters featured very dense, sometimes crowded, page compositions with lots of small panels filled to the brim with dialogue, puns, and fun expressions. As time went by, variety emerged: the compact pages slowly gave way, leaving more room to more ambitious, spacious, and creative compositions. Characters were the focus, and they acquired all the room they needed to express themselves.

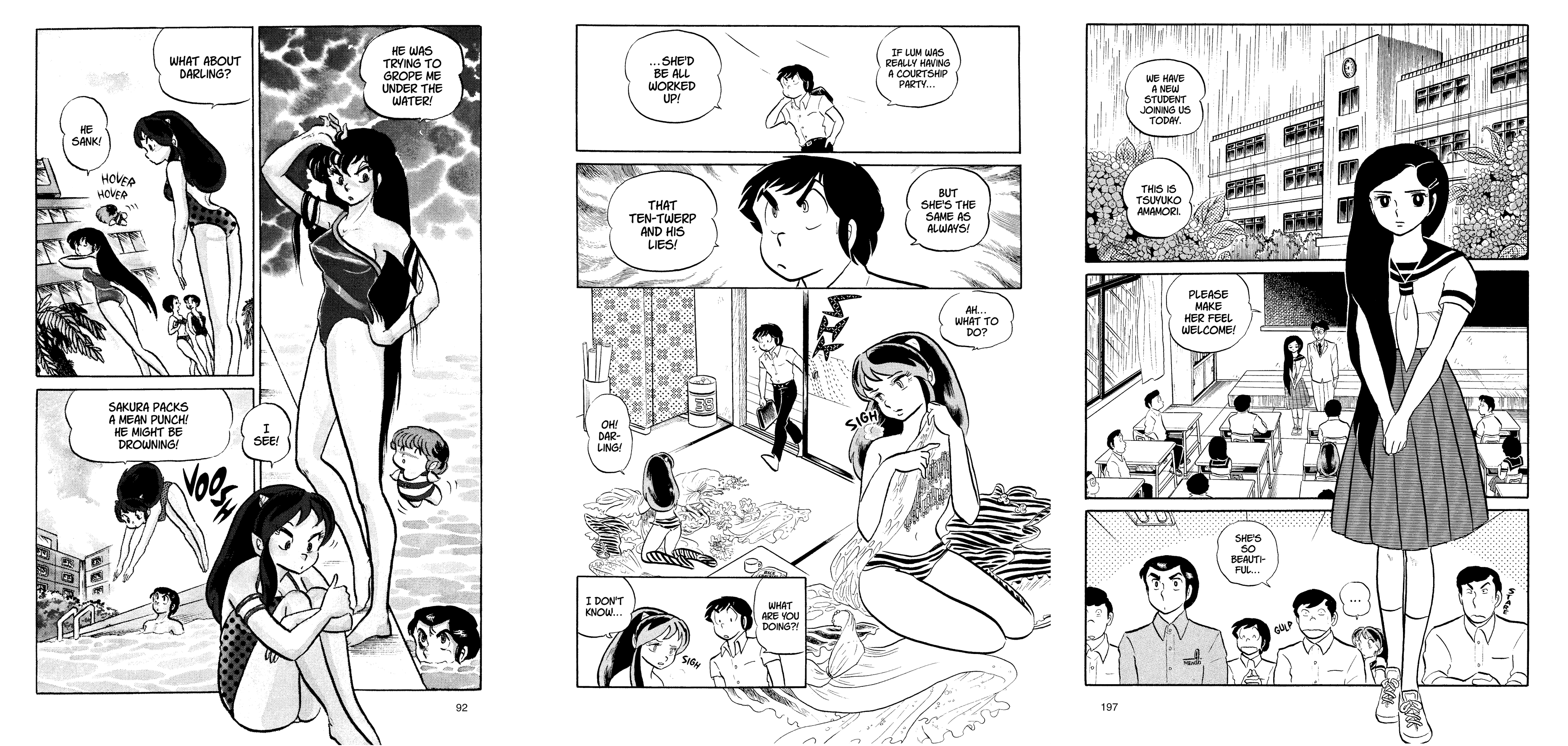

One of the typically very dense pages of the early manga, filled up by long dialogues, occupied by multiple actions/gags going on at the same time, and rather simple, compact paneling

Before going into the detail of these stylistic evolutions, let’s generally review the three main directions Urusei Yatsura took after its first 10-or-so chapters, which largely flowed from Lum’s increasingly important role.

The first is that Urusei Yatsura quickly managed to strike a chord with an emerging part of the manga readership: lolicon fans. In the late 70s, this expression referred to male fans of shôjo manga, primarily attracted to cute girl characters who were taking the doujinshi scene by storm. The leading artist in the lolicon movement, Hideo Azuma, immediately saw Urusei Yatsura‘s appeal and famously stated that thanks to Takahashi, “manga was back in Shônen Sunday.” It would be hard to say whether Takahashi was conscious of the lolicon audience or to trace a direct line of influence from Azuma to her. But the fact is that they shared a similar mindset and that their works shared more-or-less the same conventions. Takahashi had been active in the early doujinshi world, and her manga featured the very specific kind of eroticism its members appreciated: sex was conspicuous, but things never got graphic as they had done in Gaki Deka; Lum was incredibly cute (and Takahashi’s incredible sense for quirky expressions only intensified that) and innocent, and yet she walked (or rather flew) around exhibiting her sex-appeal in her tiger-skin bikini. As a journalist in Animage noted in November 1981, “there’s nothing dirty about Lum’s sexiness.” This particular balance was exactly what young male otaku and their obsession with purity wanted from female characters.

The other thing about Lum is that she’s a completely foreign existence. To the same degree as the unlikeable and unlucky Ataru, she is an agent of chaos. If the early chapters were absurd and over-the-top, those that followed went even further. With Lum’s dual nature as an alien and oni, the two dimensions of SF and folklore were freely mixed-up to create an unprecedented degree of nonsense. But, at the same time, nonsense became a part of daily life and lost the absurd value it had early on: things are weird, and that’s how they are. A key factor in that was Takahashi’s age: admittedly older than most readers of a shônen magazine, she was still extremely young. For that reason, the concerns and themes she raised were not divorced from those of her readership, and the many pop culture references she conjured looked and felt familiar. All these factors together made Urusei Yatsura an explosive cocktail.

But there was another thing, perhaps even more significant. In the early chapters, the characters held extremely conventional roles – the main character, his parents, his friends, the neighborhood, and the offbeat priest cracking weird gags. Centering things on Lum, and progressively adding a cast of characters who were all weirder than the others, totally changed the internal dynamics of the story. Most importantly, a love triangle entered the picture. This fundamentally changed Urusei Yatsura, which transitioned from a classic slapstick comedy to a love comedy.

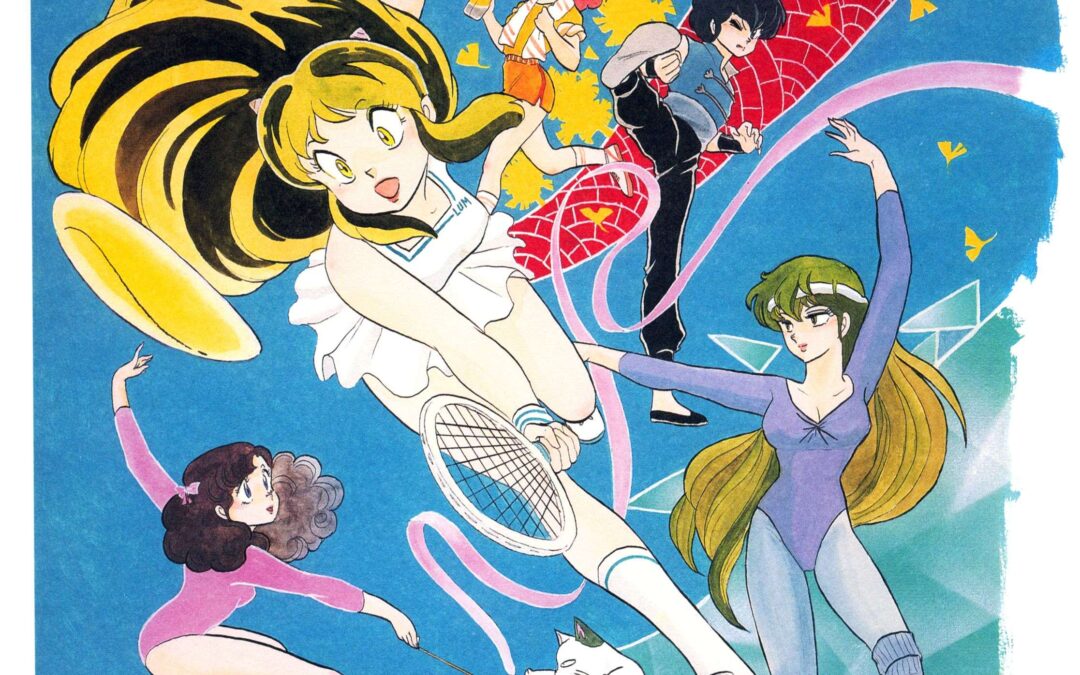

Urusei Yatsura’s influence over love comedy in manga history should not be overstated. The genre’s development can be retraced in postwar shôjo manga, following a genealogy that goes from Hideko Mizuno to the otomechikku movement through Yoshiko Nishitani. But these works from the 60s and 70s usually focused on “normal” highschool girls in “normal”, contemporary Japan. And most importantly, they were written by women, for girls. Urusei Yatsura added the SF and slapstick elements, but it was also published in a shônen magazine – in other words, it was aimed at male teens. For that single reason, Urusei Yatsura’s impact should not be understated either. Takahashi would drive the nail even deeper in 1980 with Maison Ikkoku, an even more textbook love comedy, published this time in Shogakukan’s Big Comic Spirits – that is a seinen magazine. Love comedy’s entry into male-oriented media was a turning point in manga history. Shogakukan would capitalize on Takahashi’s success to promote another young artist, Mitsuru Adachi, with Miyuki in 1980 and then Touch the next year, which ran alongside Urusei Yatsura for all of its serialization. It would take more time for other publishers to truly follow suit, but Shûeisha found its own flagships with Hisashi Eguchi’s Stop!! Hibari-kun in 1981 and Izumi Matsumoto’s Kimagure Orange Road in 1984.

Shûtarô Mendô, “Zodiac cycles” and Takahashi’s growth

In order to understand more specifically how good and innovative Urusei Yatsura was as a manga, let’s focus on one single chapter: the 23rd one, “Zodiac Cycles”, published on March 19, 1980. It is relatively early but perfectly illustrates the transition still going on in Takahashi’s art, and it is in my opinion one of the best and most impactful chapters of the entire manga – something that cannot be said of its anime counterpart.

This chapter immediately follows the introduction of a new character: Shûtarô Mendô. Mendô was quickly integrated into the main cast for a variety of reasons, showcasing how character-centric Takahashi’s comedy was. First, Mendô is both Ataru’s foil and double, creating a complex dynamic of rivalry and imitation between the two, the base for one of the manga’s strongest comedic duos. Since Mendô is a boy (unlike most of the secondary cast), he also makes the character relationships far more complex: the Lum-Ataru-Shinobu love triangle becomes a square in which Mendô loves Lum but is loved by Shinobu – the exact reverse of Ataru’s situation.

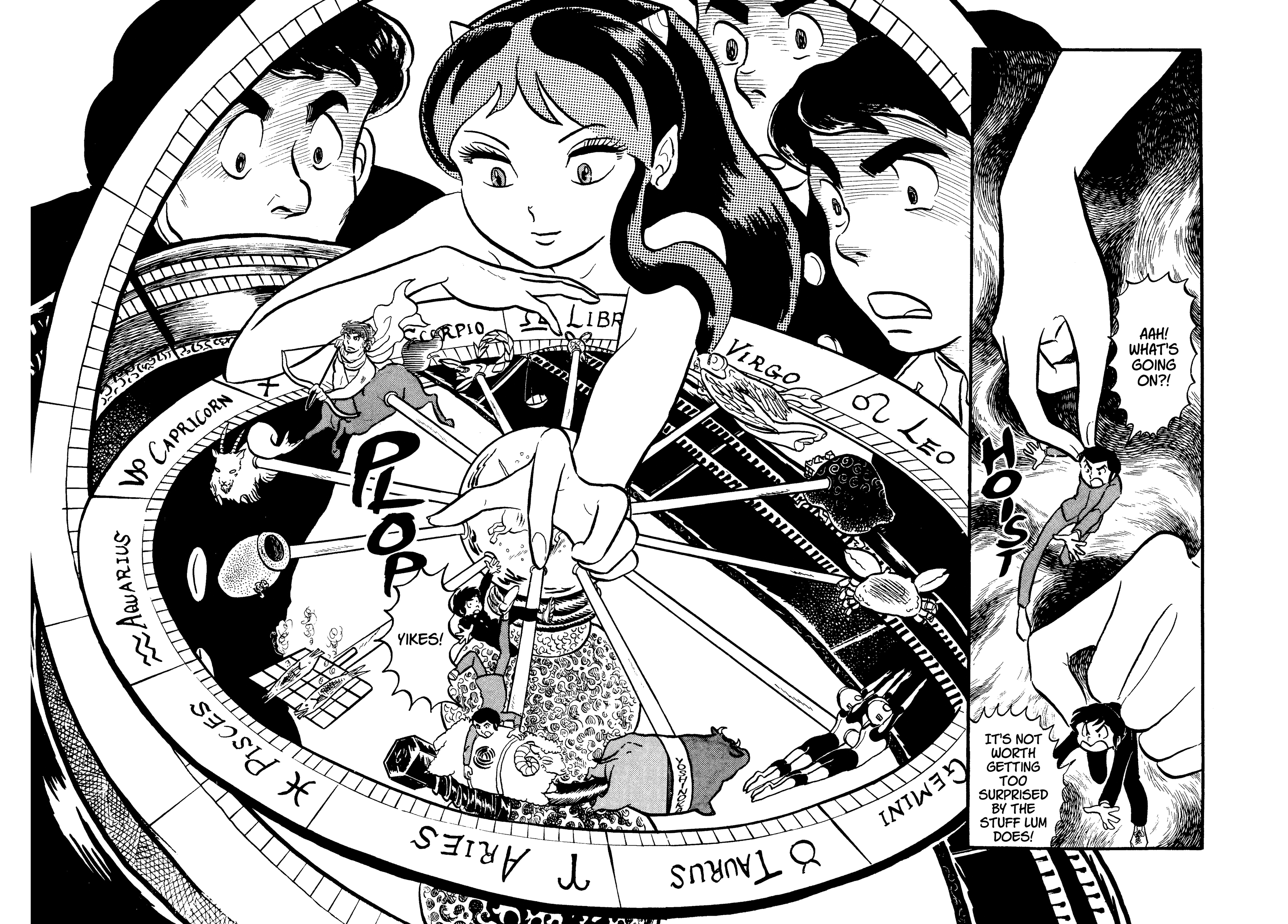

In “Zodiac Cycles,” all these elements are revealed: the chapter opens with Lum’s computer stating that she is more compatible with Mendô than with Ataru, and it ends with the announcement that both boys have the same degree of idiocy. These form the two extremes, a comical opening and ending, but what’s important is how Mendô actually threatens the relationship between Lum and Ataru – for Lum to reaffirm it in the end since she loves her Darling best.

With “Zodiac Cycles,” Mendô doesn’t only challenge the established relationships, but he also provokes a change in setting. From his appearance onwards, Urusei Yatsura would switch from a neighborhood comedy to a school comedy, and Lum’s enrollment into Tomobiki Highschool would soon follow. This specific chapter is an interesting moment of transition: as in the early phase, the crowd of anonymous onlookers still plays a significant part since it always observes the main action from the outside and fills up the multiple crowd shots that had already become Takahashi’s specialty. On the other hand, this crowd is just Ataru and Mendô’s class and already announces a recentering of the action around those two’s immediate circle.

Visually, this chapter is remarkable for the ambition of some of its panels. It even features one of Urusei Yatsura’s first double-page spreads, an impressive composition illustrating Takahashi’s complete mastery of drawing, perspective, and anatomy. The reader’s point of view seems to be included into the page, centered around Lum, while Ataru and Mendô’s unexpected shrinking illustrates her now-dominant presence in the manga. While this is undoubtedly the chapter’s most impressive moment, as a whole, it is a perfect example of Takahashi’s artistic evolution. This and a few other pages are ambitious, well spaced-out and easy to follow, while many others retain the cramped dimension of the early part of the manga – which is perfectly appropriate here as characters become microscopic. Things would just keep progressing from there, and by the time Maison Ikkoku started its own serialization, Takahashi had attained what can be considered her full-grown style.

Fuji TV, Kitty Film, Studio Pierrot: the Urusei Yatsura franchise

Getting it to TV

In 1981, Shogakukan executives must have been somewhat anxious. Urusei Yatsura was seemingly at the peak of its popularity: it had won the Shogakukan Best Manga Award the previous year, and its seven tankôbon volumes were nearing the 2 million sales mark. No one could say for how long this would last. Moreover, Urusei Yatsura’s rival, Akira Toriyama’s comedy Dr. Slump had received its own animated adaptation in April and would soon follow Urusei Yatsura as one of the winners of the Shogakukan Manga Award. It was time to bank on the situation: an anime adaptation was in order.

It seems that adapting Urusei Yatsura to TV had been in people’s minds as soon as the manga started serialization. Multiple anime studios were approached without success, and it is even said that tokusatsu studio Tsuburaya Production offered to do a live-action series. But in the end, the ones to obtain the rights would be a company that had barely been involved with anime before this and didn’t even have their own animation studio: Kitty Films. This young film company had produced cult movies such as Almost Transparent Blue or The Man Who Stole the Sun (both in 1979) and had collaborated with TMS and Tôhô for the release of the Chie the Brat film in 1980, but they were mostly new to the animation business and on the verge of bankruptcy. It happened the usual way things go in the anime industry – through personal connections and a bit of luck.

The key actor in brokering the Urusei Yatsura deal was Kitty Film producer Shigekazu Ochiai. A film graduate, Ochiai had worked as a scriptwriter and befriended manga artist Kazuo Koike, becoming the assistant director of his Gekiga Sonjuku school in the late 70s. Ochiai had also tried out the anime industry, having been a member of studio Tatsunoko somewhere between 1973 and 1974. But he became independent and, in 1979, joined Kitty Films. From there, Ochiai tried acquiring the rights from Shogakukan early on in Urusei Yatsura‘s serialization: he knew Takahashi’s talent and was convinced that something had to be done with it. However, he had difficulty finding a sponsor and a TV channel, and only after years of negotiation did Ochiai strike a seemingly perfect deal: Fuji TV agreed to air Urusei Yatsura on their primetime slot on Wednesdays at 19:30.

For the actual animation production, Ochiai turned to one of his former Tatsunoko acquaintances: Yûji Nunokawa, the director of the newly-created Studio Pierrot. In 1981, Pierrot was fresh out of its first production and success, The Wonderful Adventures of Nils. It was quickly growing, but as a result, most of the studio’s staff was busy with other projects. Because of this, the key members of Urusei Yatsura‘s leading team would be young, relatively inexperienced artists, all in their early 30s or late 20s. Conditions were harsh for chief director Mamoru Oshii’s team: first, Ochiai had difficulties finding a sponsor and gathering the sufficient budget. Maybe Urusei Yatsura was a popular manga, but it wasn’t exactly the most merchandisable thing out there. Moreover, Kitty’s producer was competing with another company for the promised timeslot. He only got Fuji TV’s official approval on August 22nd, 1981, for an anime that would begin airing in October; the preproduction had started in July, but this was still an extremely short time frame.

In the minds of Ochiai and Fuji TV producer Tadashi Oka, Urusei Yatsura was meant to be a trendy, all-ages and all-audiences anime. Their ambition is best expressed in a promotional text published in November 1981’s Animage: “If we had to explain [Urusei Yatsura’s appeal], we could say that ‘there’s nothing dirty in Lum’s sexiness’ or that ‘it’s an absurd slapstick comedy’. But these are just words. People are still going to say, ‘it’s just a cartoon’. But what about a fashionable work that makes girls who like tennis and surfing say ‘this is the only [cartoon] I watch’? That is ‘City SF Anime’.” Urusei Yatsura was therefore meant to reach people beyond the emerging otaku audience, and even beyond the shônen audience of the original manga. For Yûji Nunokawa, it should even aim for young children: it was the reason why Jariten was added as soon as the second episode. These hopes probably crumbled less than ten minutes into the first episode when, facing the opposition of all the producers on the project, Mamoru Oshii managed to expose Lum’s naked breasts on national television.

A perfectly unoriginal show

Urusei Yatsura came out in the middle of a golden age for TV animation in Japan. After a low point of 25 new TV series in 1978, the number of productions steadily increased to reach its peak in 1981 with 47 new works – a record that would not be broken until the historically-high 1998 with its 77 new shows. Just like the manga had managed to catch the zeitgeist of the late 1970s, the anime was riding on the trends of the early 1980s. But, unlike the manga, it was anything but original.

A glance at anime magazine covers of November 1981 helps get an idea of how Urusei Yatsura was initially understood. Animage heralded the coming of an “SF anime renaissance” in which Urusei Yatsura’s “City SF” style figured alongside the pulp sensibility of Space Adventure Cobra, the grittiness of Fang of the Sun Dougram, the occult Makyô Densetsu Acrobunch, the dramatic Six God Combination Godmars, and the futuristic settings of Future Police Urashiman and Technopolice 21C. On the other hand, Animedia commented on the new “Pinky Wave in Animation” represented by Urusei Yatsura, Miss Machiko and Dash Kappei.

Retrospectively, however, Urusei Yatsura can be said to fit in a third, more notable trend: the revival of long-running comedy series. This genre had been constitutive of anime and known a golden age in the early 1970s, carried by studios like Tôei (with magical girl series like Himitsu no Akko-chan and Mahô no Mako-chan or works like GeGeGe no Kitarô) and Tokyo Movie (with its Fujiko Fujio adaptations such as The Gutsy Frog or Tensai Bakabon). By the end of that decade, it had mostly disappeared, only represented by children’s shows like Doraemon, but then suddenly went through a revival in the early 1980s. Tôei made its comeback with Dr. Slump in 1981, Patalliro in 1982 and Gu-Gu Ganmo in 1984, while Tsuchida Pro was starting to specialize in it with its work on Game Center Arashi and then Sasuga no Sarutobi in 1982. Even TMS shortly came back on the scene with its New Gutsy Frog in 1981. Urusei Yatsura’s initial choice to split each episode into two self-contained stories was the most conservative of the bunch: this format was highly reminiscent of Tokyo Movie’s 1970s comedies.

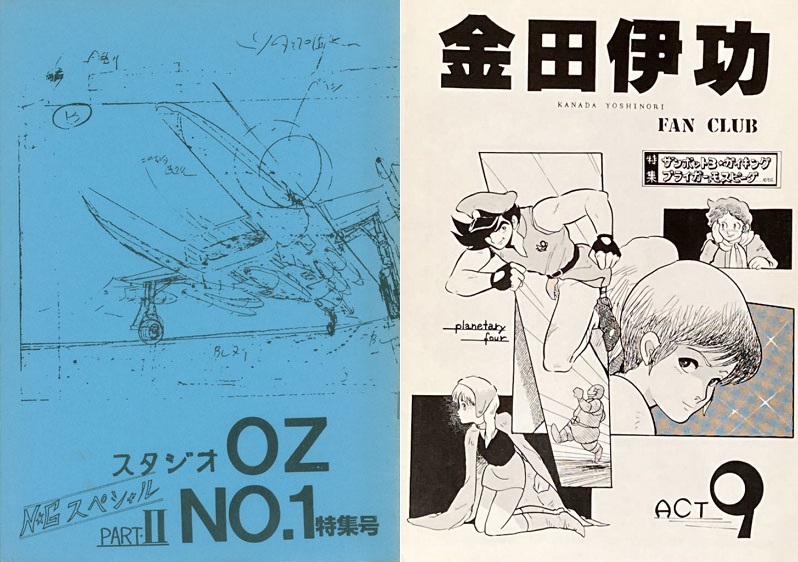

All these series didn’t just share the same genre. They also had very similar tones and approaches. They were all absurd, slapstick comedies with a strong pop-culture sensibility. Moreover, the best among them were a platform for a new, ambitious and creative generation of animators: encouraged by their nature as otaku and by their admiration for star animator Yoshinori Kanada, young artists desperately sought for new ways of animating and inserting their own interests and sensibilities in their work. The tidal wave of Kanada imitators spread like wildfire between 1980 and 1982, first on mecha series (Baldios, Acrobunch, Godmars), then comedies (Urusei Yatsura and Sasuga no Sarutobi) and then even children’s shows (Minky Momo). Among all these, Urusei Yatsura was perhaps the most successful and impactful, but it was certainly not the only one.

From then on, the battle over ratings was fierce. For most of its run, Urusei Yatsura was among the top contenders but never quite on top of the podium. Tatsunoko’s Dash Kappei, which ran on Fuji TV on Mondays at 18:00, always oscillated between 15 and 20% ratings; the same applied for Sasuga no Sarutobi, on the same channel just one hour later. The biggest rival, however, was Dr. Slump, which aired on the timeslot just before Urusei Yatsura: while the latter frequently passed the 20% audience bar, it almost never overthrew the former’s top position, comfortably situated around 30% until mid-1982, and almost never falling below 20%.

However, Urusei Yatsura had other resources. On the suggestion of Shônen Sunday editor Kazuki Tanaka, Kitty went along with producing feature films alongside the TV series. This was a bold move: at the time, the only studios with enough capacity to make long-running series and franchise movies at the same time were those that benefited from a large staff base and were working on huge franchises. Concretely, this only meant two companies: Tôei (Dr. Slump) and Shin-Ei Animation (Doraemon). The rest of anime films were either recaps or sequels to TV series (see the Gundam movie trilogy, the Baldios or Ashita no Joe movies…) or standalone productions made by specialized studios (such as Madhouse and, soon, Ghibli). But Urusei Yatsura was too big to be stopped and benefited from 4 movies during its 5-year run – at the cost of the burnout of its two chief directors, Mamoru Oshii and Kazuo Yamazaki, and probably of countless other staff members.

Lum’s many love songs

As harsh as the competition may have been on airwaves and in theaters, Urusei Yatsura’s greatest asset and source of income was outside of animation. Kitty Films was not a standalone company: it was the subsidiary of the larger music publisher Kitty Enterprises. Music would therefore play a large part in Urusei Yatsura’s production model, and the show’s success accelerated a tendency in the anime business that had begun in the late 1970s: the increasing prevalence of music companies.

The starting point was, as many things at the time, Space Battleship Yamato. Following the success of its 1977 recap movie and inspired by Star Wars’ model, Nippon Columbia started releasing symphonic suites and rearrangements of the franchise’s soundtracks. Soon, every anime had to have its soundtrack released on LP – even as, according to Fred Patten, “most of the TV cartoons before 1977 did not have enough complete songs to fill an LP”. By the early 1980s, everybody was riding on the trend. But there was one notable difference with Urusei Yatsura: the music company wasn’t just an outsider acquiring the rights from the animation studio – it was the one driving the entire project. The Urusei Yatsura anime was therefore largely built with music in mind.

First, it would have to be in touch with the music people liked. The series would have two composers, Shinsuke Kazato for the instrumental and orchestral parts and Fumitaka Anzai for the electronic music parts. This was actually a turning point in anime music history: according to Anzai, “back then, synthesizer-made BGM for TV programs was regarded as taboo, for it dissolves in with sound effects.” This instantly made Urusei Yatsura sound modern and close to the City Pop vibe it was going for. But the real hit was, of course, the show’s first opening, Lum no Love Song. The debut single of Yûko Matsutani was an incredibly catchy and trendy tune that sold exceptionally quickly. Accompanied by Kôji Nanke’s energetic animation on TV, it remains one of Urusei Yatsura‘s greatest sources of appeal to this day.

This success was too good to pass on, and Kitty went a step further: Urusei Yatsura would regularly change its opening and ending songs and sequences for the first time in anime history. Of course, all of this to release those songs on records. It’s possible to count the number of releases between 1981 and 1986 – without forgetting that these didn’t stop once the anime ended its run but kept going for years.

5 BGM albums were released for the TV series between 1982 and 1985, while each movie benefited from both a BGM and an audio drama album. Then, we find 10 compilation albums, half of which were released in 1986, probably to send off the anime. But the highest number is that of singles, which goes up to 20. To all this, we must add 4 jam trips and one “synthesizer fantasy,” all made up of instrumental covers of the music or songs from the show. As Fred Patten summed it up, “cartoon music records had been a major merchandising sideline for many years by this time, but in this instance the cartoon was practically a sideline of the music industry.”

Kitty’s role in Urusei Yatsura didn’t just affect anime music or merchandising. It would have long-lasting effects on the structure of the anime industry thanks to a new format that emerged as the TV show was airing: OVAs. Direct-to-video productions completely changed the power balance in anime business, as the regular partners of animation studios, TV channels and advertising agencies, were now irrelevant. Still, all these new works had to be paid for somehow. Music companies would be there to provide that money, in exchange for the systematic addition of insert songs and opening or ending themes that could be sold as records. Kitty’s direct involvement with the OVA market would be scarce; but, by showing that music companies could greatly benefit from obtaining direct control over anime production, it largely set the stage for the business model of the OVA boom.

Urusei Yatsura: the rise and fall of “anime’s New Wave”

A rough start

The pressure on the creative team gathered by Yûji Nunokawa in Studio Pierrot must have been extremely high. Not only were they adapting one of the most popular mangas of the day on an extremely tight schedule: they were basically a bunch of inexperienced nobodies, and all eyes were on them. During the first months of Urusei Yatsura‘s airing, most anime magazines’ coverage of the show was dedicated to understanding who the young artists leading the show were and what their vision was – if they had one in the first place. This provides a rather detailed view of the behind-the-scenes of the anime’s early production.

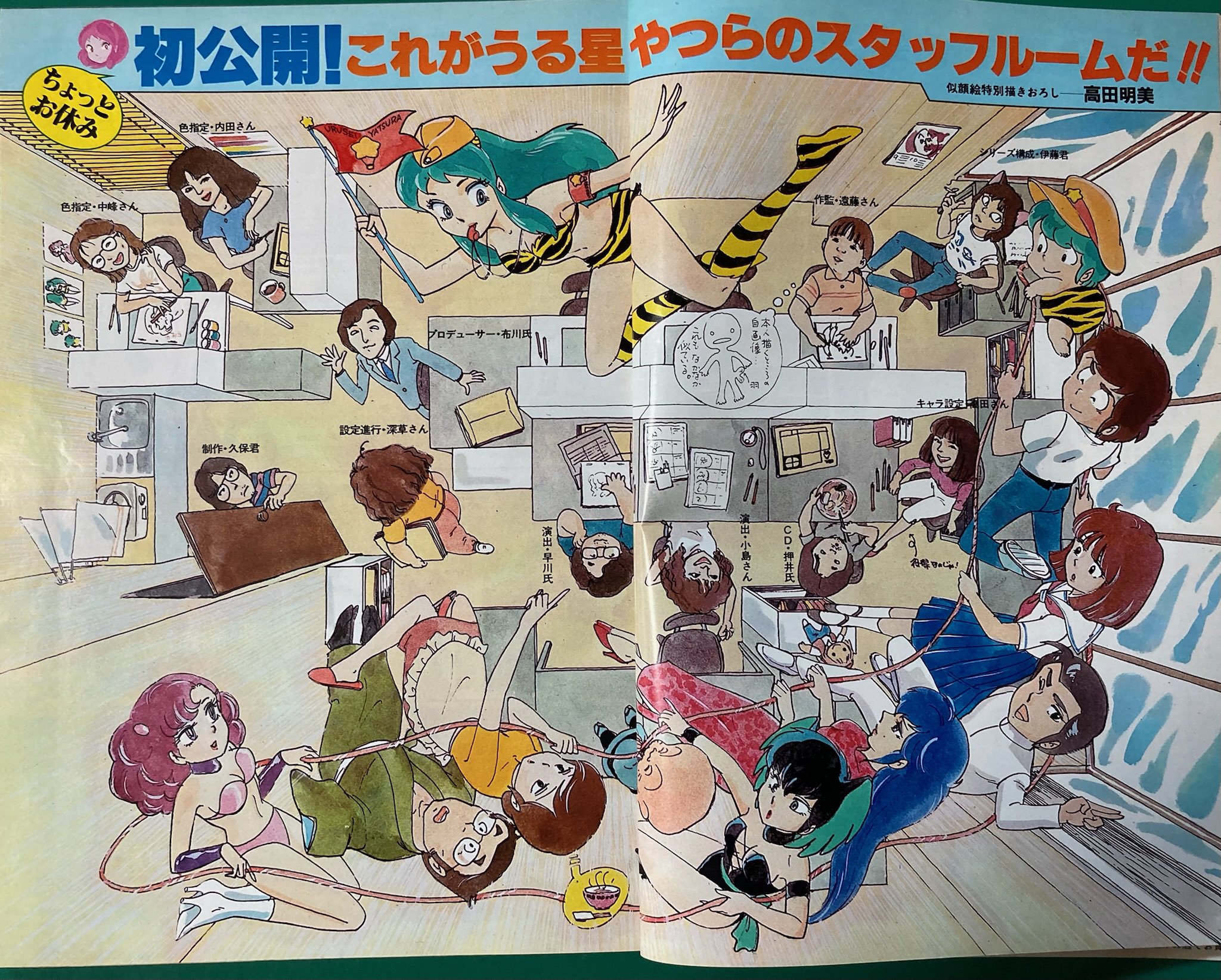

Besides the main staff’s youth, journalists quickly noticed the number of women on the production, notably the character designer Akemi Takada, chief animation director Asami Endô or episode director Tamiko Kojima. This was a significant element in the early discussion of the show since the manga had also been written by a woman. In November 1981, Yûji Nunokawa explained how the gender of its creators played a major part in Urusei Yatsura‘s appeal:

“When you look at the original work, there’s a lot of problematic and questionable material, but I think that because the author is a woman, she can draw this kind of thing and keep things clean. If the animated version were to be made by only male staff, this questionable atmosphere would come out too directly through the movement of the animation. I don’t think we would have been able to maintain this “cleanliness”… But when it comes down to it, when selecting the team, I chose people who had read the manga and said they’d like to work on adapting it. That’s why there are so many young people in the staff. I hope their vitality can properly express itself and explode out of the screen.”

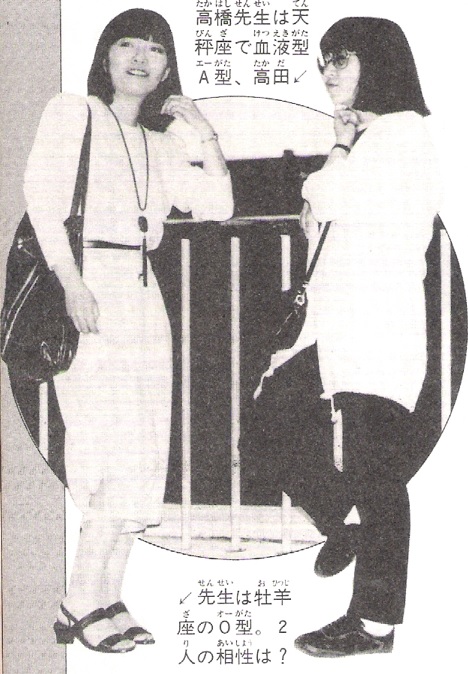

Two of the women behind Urusei Yatsura in 1982: Akemi Takada (left) and Rumiko Takahashi (right)

Needless to say, this presentation sidelined the male artists: the most experienced member of the staff, scriptwriter Yû Yamamoto, and chief director Mamoru Oshii. This discursive context is important to understand Oshii’s perspective on Urusei Yatsura, since he would always insist on the fact that his vision was a masculine one, and therefore naturally and fundamentally different from Takahashi’s. Things weren’t as clear-cut during the early months of the show, but we can already discern this line of argument in Oshii’s provocative statement that his favorite character was Ataru and his interpretation of Urusei Yatsura as a story about desire and how it circulates. It would become clearer with the first movie, Only You, which Oshii presented as follows in November 1982:

“If I had to say it with a catchphrase, I’d say that the basis for the movie was “Ataru and Lum’s love story”. But, even if I talk about a love story, what I personally wanted to depict was a world in which women are superior to men, and a story in which women have more life to them than men. I wanted to show what a woman’s overflowing energy looks like from a man’s point of view.”

However, before reaching such a clear understanding of where he wanted to go, Oshii and his fellow storyboarders faced one immediate challenge: how could they adapt Takahashi’s writing and pacing to animation? As mentioned above, the manga was notable for the density of its pages and the constant activity of the characters. Considering the differences between the mediums of comics and animation, the main issue was fundamentally one of pacing. Could animation match the extremely rapid rhythm of the manga?

Oshii considered this very seriously and concluded that the anime should leave the viewer no time to rest: any useless dialogue or exposition would be cut, and the animation would carry most of the load. Through what he called “omission”, Oshii’s storyboarding philosophy relied on long cuts: “I’m thinking of using one single shot for scenes that would usually require 10 cuts”. Looking at the first episode, it’s easy to see what kind of shots Oshii had in mind and how effective such an approach could be.

What made this so necessary was an additional constraint, probably imposed by Nunokawa and Ochiai: to divide each 22-minutes episode into two 11-minutes stories, each adapting one chapter of the manga. The idea was that making each story so short would force the staff to condense things as much as possible and match the manga’s pacing. This certainly worked in a few cases but generally mostly backfired. The anime’s half-episodes often cut material from the manga, removing most of the nuance and reducing Urusei Yatsura to a series of gags mechanically following each other rather than a character-driven comedy focused on relationships. Moreover, in spite of Nunokawa’s assurance that the anime’s staff was young and understood the essence of Takahashi’s work, the (understandable) choice to immediately make Lum the center of the show put scriptwriter Yû Yamamoto in a difficult situation: in such conditions, it was impossible to convey the so-called “dry” tone of the early chapters of the manga. On the other hand, the more character-focused dimension that came in later was also impossible to truly render in half-episodes.

In other words, Urusei Yatsura’s production had imposed constraints upon itself that made sense on paper but actually made it impossible for the series to develop. This became obvious, by a strong contrast effect, when the show’s first truly great episode aired: episode 10, “Pitter-Patter Christmas Eve”. It was the first time a single story would occupy a full episode’s run, and it was a resounding success (it is to this day one of the most popular episodes in the show). The longer runtime enabled Yamamoto and Oshii to add original material rather than cut gags from the manga. There, voice actor Shigeru Chiba, playing the part of “Male Student A”, fully revealed the measure of his improvisation talents (he would rewrite his own lines in the script most of the time) and imposed himself as one of the most important figures in the cast. His character acquired a name, Megane, and would play an essential role in the development of Oshii’s vision.

Moreover, for the first time, the director had the occasion to demonstrate why Ataru was, for him, the most crucial character in the show: the episode explored his psychology, his attachment to freedom and the meaning of that freedom – to instinctively follow one’s desires without any limits. Lum’s feelings weren’t ignored either, and for the first time, Urusei Yatsura could deserve the qualification of “love comedy”: “Pitter-Patter Christmas Eve” is a story of friendships, rivalries, conspiracies, misunderstandings – everything one could expect from the genre. In other words, episode 10 was the first time the Urusei Yatsura anime showcased a real understanding of the characters and their feelings in order to create a real story rather than just a series of gags.

With time, Ochiai and Nunokawa realized that the two stories per episode formula worked against the show: they abandoned it once its “first season” had concluded, that is from episode 22 onwards. However, there remained one major problem: Urusei Yatsura’s animation was dismal. The show’s A team, the trio formed by Asami Endô, Motosuke Takahashi and Naoko Yamamoto from Studio Dôtaku did excellent work, but the other teams in Urusei Yatsura’s rotation were not quite as competent. When things moved, they moved badly, and when they didn’t, drawings were rarely pleasant to look at. Oshii wanted the show to be carried by its animation; but the animation was too weak to carry anything.

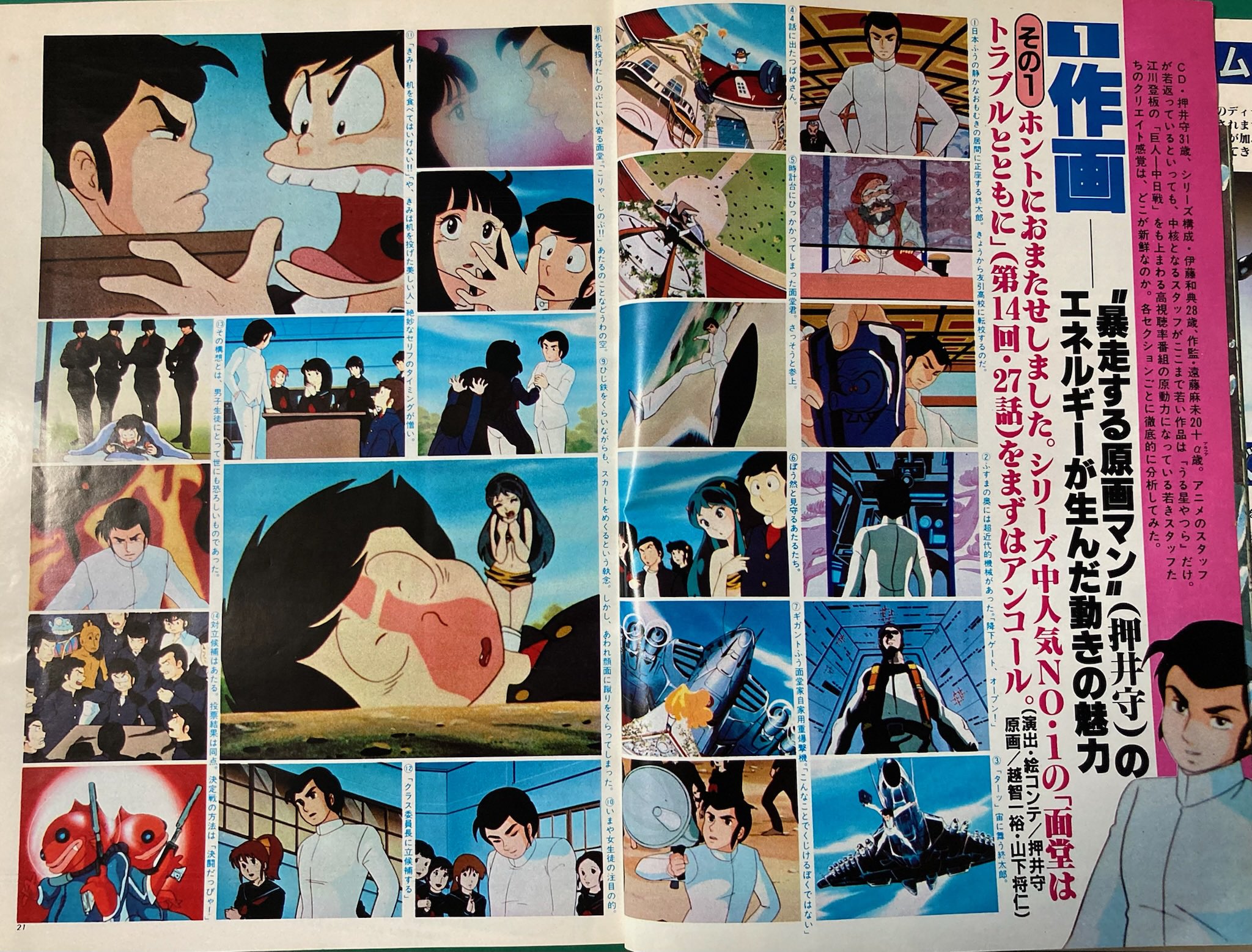

Things didn’t suddenly get better, and it took the entirety of the show’s “first season” for the rotation to get more diverse and for young, ambitious animators to arrive and stretch their muscles. But there is one identifiable turning point: episode 14A, “Mendô Arrives With Trouble!”, entirely handled by two up-and-coming animators, Kazuhiro Ochi and Masahito Yamashita. From Studio NO.1, they were the brightest students of the most popular animator of the day, Yoshinori Kanada, and had made themselves noticed on Tetsujin 28-go and the Space Warrior Baldios movie. In a November 1982 interview published in Animage, Mamoru Oshii and Keiji Hayakawa recalled their impressions of Ochi and Yamashita:

“Oshii: I met these two last winter… They couldn’t meet the deadline, and I’ll never forget how they just brought instant ramen and spent a week sleeping in Pierrot (laughs). First, they showed me their drawings from Tetsujin 28-go and Godmars, which are really unique, right? I really wanted to know how it would look if they drew humans rather than robots. But I was very anxious until I saw their drawings.

Hayakawa: The acting was totally different from what you usually see. I couldn’t imagine what to do with their drawings. When I draw storyboards, I have an image of how things will be like, but this… the animation felt like it wanted to have a fight with the storyboard. How to integrate something like that is a real problem.”

Certainly, Ochi and Yamashita’s animation was peculiar: the movement was overly stylized and exaggerated, characters were extremely off-model… and yet, it worked incredibly well. It fit the absurd dimension of the show to a T, and one could now actually see what it meant for a comedy to be carried by its animation. No doubt, episode directors had to get used to their storyboards getting modified and animation directors to the characters looking like they came from an entirely different show. But, under Oshii’s supervision, the Urusei Yatsura staff decided that it would keep going in the way that the NO.1 duo had opened: soon, the show would attract young and talented artists in droves and became the hottest topic of discussion among animation fans throughout Japan.

The unstoppable rise of Mamoru Oshii

By the end of its second season, Urusei Yatsura had reached cruising speed. Masahito Yamashita had joined the studio’s regular rotation alongside his friend from their new studio OZ, Shinsaku Kôzuma. Future titans of 80s animation slowly followed in their wake: Toshihiro Hirano first joined the production on episode 15, Katsuhiko Nishijima on #18, Hiroyuki Kitakubo on #43, Yûji Moriyama on #47… They, and many others, turned the show into an animation powerhouse. But that was not all: with every new episode, Oshii’s direction seemed to improve, while Yû Yamamoto, the show’s initial chief screenwriter, was replaced by the young Kazunori Itô, Oshii’s friend and Ochiai’s protégé. In other words, the show was acquiring an identity of its own, building on the manga and yet distinct from it.

By late 1982, with the announcement of the movie Only You, the critical discourse around Urusei Yatsura had radically changed. Anime journalists were no longer wondering whether the young staff would rise up to the challenge, and they were certainly not ignoring Mamoru Oshii anymore. The question on everyone’s lips soon became: “who’s this talented young director making Urusei Yatsura one of the most creative anime right now?” The director started being regularly interviewed by anime magazines: as curiosity about Only You’s production increased, writers and readers paid a growing amount of attention to the carefully chosen words of the one whom Yûji Nunokawa described as “looking like a young man who hasn’t become an adult yet”.

In his early 30s, having only started working in the industry in the late 1970s, Oshii was a perfect fit for Animage’s critical and historical discourse: under Toshio Suzuki’s direction, the magazine divided anime history into neat aesthetic and generational categories. On the one hand, there was the divide between the Tôei and Mushi lineages of animation; on the other, anime history could be understood as a series of successive “booms”: the birth of modern Japanese animation in Tôei, the development of TV anime, the Yamato boom, the Gundam boom… As the 1980s progressed, Animage’s editors started looking around for new figures who could represent a “New Wave” of artists: one of them was Yoshinori Kanada, the animator who was said to transcend the Mushi/Tôei divide and embody the new directions Japanese animation was taking in the post-Yamato landscape. Another was Mamoru Oshii, representative of a new generation of anime auteurs.

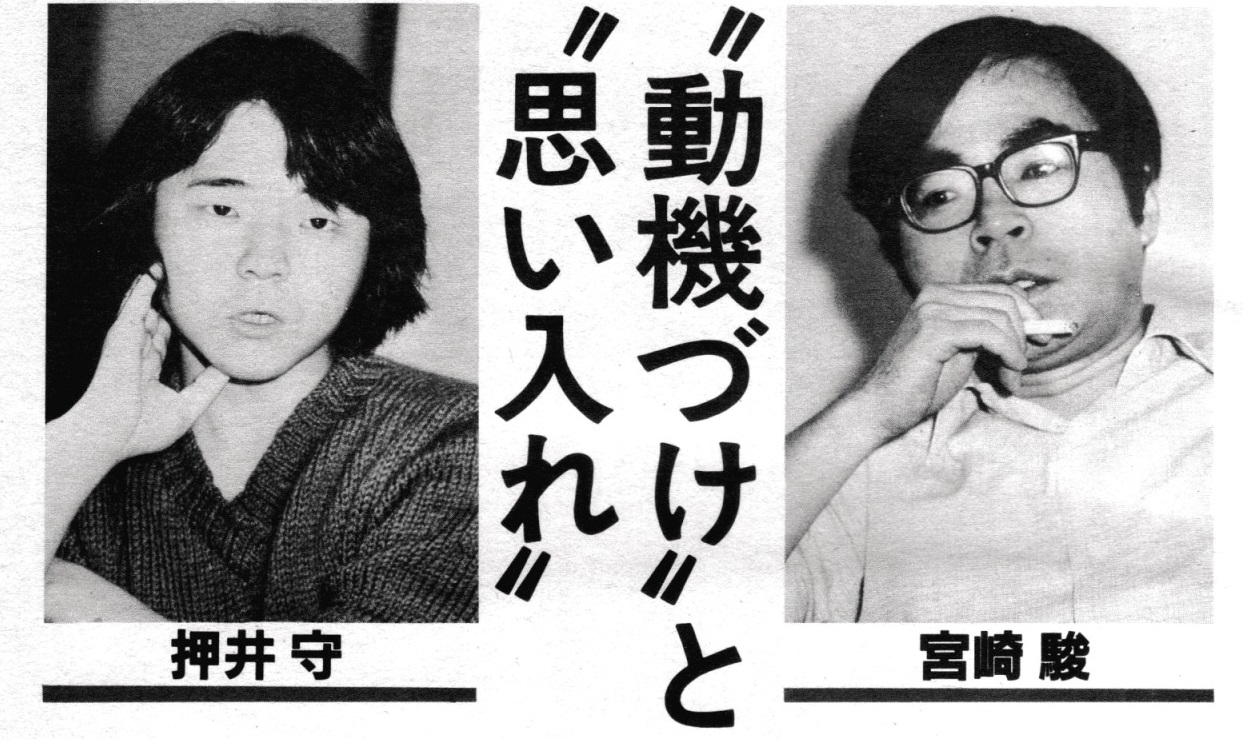

The first step in Oshii’s rise to this status was a long focus on him in the January 1983 issue of Animage. It notably contained multiple pages on “Oshii and his rivals” and a long talk between “the new guys of the third anime boom”: Mamoru Oshii, Kôichi Mashimo, Mizuho Nishikubo, and Hidehito Ueda. These four directors had many things in common: they were all young, originated from studio Tatsunoko, and some were directing some of the shows Animage was most ardently promoting. Oshii was on Urusei Yatsura, Mashimo Urashiman, and Nishikubo was about to become chief director of Miyuki. It would not be long until this group of “newbies” would be called the “Four Heavenly Kings of Tatsunoko”, a far more flattering and impressive title that would retroactively strengthen one of Animage‘s narratives: Tatsunoko’s comeback to the forefront of the anime scene with shows like Urashiman or Macross. More than the actual contents of the interview, the short presentation by Animage’s interviewer is extremely telling about the shift in discourse that was happening around these men, especially Oshii and Mashimo:

“So far, I believe Animage’s columns have focused a lot more on animators than on directors. And the directors we’ve featured so far are all members of anime’s first generation: people such as Yoshiyuki Tomino or Isao Takahata, who could be called your masters. However, since Urusei Yatsura has attracted fans’ attention, people have become aware of Mamoru Oshii’s direction and young directors have become a topic of discussion. […] So we’ve gathered you, who are the “big 4” attracting the most hopes around you for 1983.”

Oshii’s rise would only continue: the next month, he would be the focus of a new series titled “The Directors’ Point of View” with a talk with Isao Takahata, who had been, since Animage’s very first issue, heralded as the most visionary creator in Japanese animation. Not long after, in May 1983, the second entry in the series featured a discussion between Oshii and Hayao Miyazaki, yet another Animage-favorite. Once again, for my purposes here, the content of these dialogues is not really important: what matters is the symbolic dimension of these articles. Oshii had become acknowledged, and he was now on an equal footing with anime’s greatest artists. He was now a full-fledged auteur.

However, one does not simply become an auteur because the critics have said so: one needs a masterpiece to assert one’s personal style and vision. For Oshii, that was the second Urusei Yatsura feature film: Beautiful Dreamer. The movie had a troubled preproduction: commissioned by film producer and distributor Tôhô, its plot was supposed to be written by Rumiko Takahashi herself. When she proved unable to provide a suitable story in time, popular anime writer Tadashi Shudô was brought in but left following a conflict with Oshii, who submitted various ideas before writing the script himself as an ultimatum. Later, when the director submitted his storyboard, it was completely different from the script he had himself written. Still, things were too advanced to change anything and the movie’s production started, at the cost of breaking an already precarious relationship between Oshii, Ochiai and Kitty Film. In any case, Beautiful Dreamer benefited from the cream of the crop of the TV series staff (Kazuo Yamazaki, Yûji Moriyama, Masahito Yamashita) as well as one of the most famous art directors in the entire industry (Shichirô Kobayashi) and multiple extremely popular animators (Ichirô Itano, Hajime Kamegaki, Tsukasa Tannai…). It was also a manifesto of sorts for Oshii.

Carried by a direction so distinctive it was like a provocation, Beautiful Dreamer was one of the most experimental anime films ever made when it came out. And yet it was part of an extremely popular, mainstream franchise. The pacing was extremely slow, the gags odd and sparse, and Lum’s presence was reduced to a passive background role. Instead, the movie centered almost exclusively on three male characters – Ataru, Mendô and Megane – and the prodigious performances of their actors Toshio Furukawa, Akira Kamiya and Shigeru Chiba. Building on everything Oshii had done and learned on the TV series, the movie offered a total experience, with some of the best animation of the decade, an art direction that far outclassed that of the show, superb photography and outstanding performances. But, as stunning as it might have been, for many, it was not an Urusei Yatsura film. Oshii had hijacked the franchise and done something completely different.

However, Oshii offered an alternative interpretation: Beautiful Dreamer was, for him, the quintessential Urusei Yatsura work. It was Urusei Yatsura, but taken seriously and its premises carried to their logical conclusions. The movie’s structure echoed that of the TV series (endless repetition) and contained multiple direct and indirect references to its events. Moreover, every character behaved as they had always done, and Lum and Ataru’s love story was reaffirmed more strongly than it had ever been. Finally, Beautiful Dreamer thoroughly explored its two protagonists’ mindsets: Lum’s love for Ataru entails a love for everything he represents – the promise of a “normal”, fun daily life in Tomobiki surrounded by friends. Ataru’s character was finally apprehended and summed up in the paradox he submits to the ghostly child Lum at the end of the movie: to be free from Lum means being able to love her, because being bound by anything – including love – would be violating his nature. Finally, Lum was, more than than ever, put on a pedestal as a mysterious idol for all the other characters, a chaotic being who both loves the world and threatens to destroy it, all with seemingly perfect innocence. The only difference, then, was that Urusei Yatsura’s main theme, desire, had been reformulated to become dreams. But in Oshii’s perspective, this was only minor, as both are ultimately just forces emerging from the human psyche that bend reality.

The only problem was that the director was probably the only one seeing things in such a way. Amid rumors of Takahashi rejecting the movie, Oshii stepped down from chief direction in March 1984, barely two months after Beautiful Dreamer’s release, and studio Deen took up the animation production from Pierrot. Urusei Yatsura had entered its second phase.

Bitter ends

While Beautiful Dreamer was the trigger that led to Oshii’s departure, it was never the only nor the chief reason. Shigekazu Ochiai had always disagreed with the director’s perspective, and tried to have him leave as early as the end of the show’s first season, 22 episodes in. Oshii just remained thanks to Yûji Nunokawa’s intervention, and then to Only You’s success. But that movie was itself another factor, this time on Oshii’s side. Indeed, its production put him face-to-face with the paradox of his situation: on one hand, he finally had the opportunity to do a completely original story, not bound by Takahashi’s manga; but on the other, he was still incredibly constrained and would in following years describe his first film as nothing more than an extended TV episode. In a talk with Kazunori Itô published in Animage in April 1983, Oshii clearly expressed his feelings:

“Oshii: As we were making the movie, I realized that when you’re adapting something to animation, there are some absolute limits that make it impossible to do what you want.

Itô: After all, even if the movie’s an original story, we can’t destroy Urusei Yatsura’s world. […]

Oshii: Doing something 100% original is exhausting. But there’s a gap between what I want to do and Urusei Yatsura’s world, and that’s becoming a dilemma. […] We were discussing this with Itô, that we’re thinking about ditching the SF elements and things like that. Let’s stop using inter-dimensional travel stuff, and instead let’s explore each character’s individuality.”

Oshii’s new mindset had direct effects on the TV series: a few months after this interview, in June 1983, the number of original episodes, which had been close to nothing until this point, suddenly rose. Of the 35 episodes that aired between June 1983 and Oshii’s departure in March 1984, 3 were recaps and 10 completely original. Such a proportion would not be repeated anywhere else in the show. Oshii was playing with fire, and he finally set things ablaze with Beautiful Dreamer.

In summary, the sign had been on the wall for some time. But the chief’s director departure was a surprise for a large part of the staff, not least of which the one who had been appointed as Oshii’s successor, Kazuo Yamazaki. As he told it himself a few years later, Urusei Yatsura’s chief direction was simply dumped on him:

“After Beautiful Dreamer’s production was finished, one day, Mr. Oshii suddenly invited me to a café near Pierrot. He told me: ‘actually, wouldn’t you like to take up chief direction?’ ‘Wait, what?’ I answered. ‘Won’t you and Deen take over the show?’ ‘What?’ ‘Any feelings I had for Urusei are gone now, I’m done with this.’ And he left (laughs). I thought he was kidding, but it turned out to be true. […] As all this happened and became real, I was there thinking, so that’s how this industry works, huh? We’re all just going with the flow… That’s crazy (laughs).”

Even if we account for the probable exaggeration here, the fact is that Kazuo Yamazaki, a veteran animator who had “signed up” for Urusei Yatsura and became an essential part of its rotation, didn’t want to direct. Just like Oshii had burnt out and felt the series to be increasingly stifling, Yamazaki slowly developed a strong distaste for it and its fans. The result was his second movie and the fourth in the franchise, Lum the Forever.

Yamazaki’s response to Beautiful Dreamer didn’t just reference it and acknowledge its place within the franchise; it also revolved around similar themes, a horror movie atmosphere, a slow pace and a flurry of meta-fictional devices. In many of these aspects, and as a whole, Lum the Forever doesn’t equal its predecessor. But it does go further than it in one central way: it is a direct challenge and an attempt at undermining the very foundations of Urusei Yatsura.

Oshii had created a post-apocalyptic Tomobiki, but Yamazaki destroyed it to the ground. Oshii had made Lum passive, but also the center around which the entire world turned; Yamazaki eliminated Lum and tried to create a world without her. In Beautiful Dreamer, dreams interfere with reality because they are an expression of the characters’ selves and what they (or others) believe to be their fundamental desires; in Lum the Forever, dreams are quite literally other realities, possible worlds in which the characters may live other lives in which Lum is absent. Both movies were parallel and different, and their creators’ attitudes were as well. Oshii’s successive provocations were directed at Takahashi and Ochiai, whom he felt stifled his creativity: keeping with his growing auteur image, he played the role of the lone artistic genius having to fight with the uncreative world of business. Yamazaki, on the other hand, was just tired of it all and addressed all his defiance to the fans of a work he just didn’t understand anymore. As he summed it up in 1997,

“The work of a director is really tough, and about that time I was starting to want to get out of it. […] I was getting a lot of letters from fans, saying how much they loved Lum and whatnot. I wanted to tell them that they should not focus their entire lives on the series but that they should move out, get some exposure to real life, get a life (laughs). Life’s too precious to be wasted: that’s the kind of message I wanted to put into the movie. […] The story I’d wanted to tell was about the Urusei Yatsura world, Tomobiki-cho, being one living organism. Within that organism, the foreign object called “Lum” would be intruding. […] I don’t think I was as skilled back then, when I made Lum the Forever. When it came out in the theaters, I bought a ticket and went over to see the movie. And when the movie was over, I was leaving the theater, and saw two boys, about 10 or 11 years old, come out, looking rather disappointed, and one of them kicked the floor and spat. Hence, I regretted what I made, and I’ve sworn never to make a work that lacked entertainment, even if it had a serious message in it.”

Yamazaki’s farewell to Urusei Yatsura was therefore a bitter one, in more ways than one. As the TV series abruptly ended, plans for a 5th movie were temporarily put off. However, this should not obscure the fact that the decision to put Yamazaki in charge of the series had been a good one. He had a deep understanding of Urusei Yatsura and how to make it work, and some of the episodes he directed in both the Pierrot and Deen parts are among the best in the entire show. Blessed with a visual sense rivaling Oshii’s, Yamazaki always put the characters at the center, creating genuinely touching drama. However, the circumstances were against him: the Deen phase which he oversaw was a slow and painful decline.

The exact circumstances which led Pierrot to drop out of Urusei Yatsura remain unclear: when Oshii left the show’s production, he also quit his studio and went freelance. Pierrot’s departure was therefore apparently not a necessity. The most likely possibilities are therefore either that Shigekazu Ochiai wanted Pierrot as a whole out of his show, or that Yûji Nunokawa, in solidarity with Oshii or for business reasons, decided to take the occasion and move out. And that certainly benefited his studio, which could launch its first fully independent production, Magical Angel Creamy Mami. The consequences on Urusei Yatsura, however, were not so good.

What had made Urusei Yatsura so exceptional was its staff rotation, and that was largely thanks to the network built by Pierrot’s artists and producers. With them gone, the rotation changed and the series with it. Admittedly, some of the most interesting artists from the first part remained, such as Katsuhiko Nishijima, and some new, talented ones like Tsukasa Dokite joined as well. But that was nothing compared to the losses: one by one, Asami Endô, Motosuke Takahashi, Yûji Moriyama, Masahito Yamashita, Toshihiro Hirano, Hiroyuki Kitakubo and many others dropped out from the show. Urusei Yatsura never collapsed or went back to the disastrous level of its early episodes; but the gap between good episodes on the level of those from the show’s golden age became longer and longer until the series became one long, boring sludge out of which sometimes emerged a jewel.

The change in studios and rotations is the most simple, concrete explanation for this downfall. But more generally it is necessary to acknowledge that, already by 1985, Urusei Yatsura belonged to another time. Animated shônen adaptations were entering another stage with the beginning of Dragon Ball‘s run in February 1986. Moreover, the OVA boom was in full swing, the entire industry was afraid that the end of TV anime had come, and all that Urusei Yatsura had represented – experimental direction, pop culture references at every corner, episodes entirely carried by their animation, absurd and over-the-top scenarios – had found far more fertile soil to grow on.

When Urusei Yatsura‘s spiritual successor, Project A-Ko, came out, a mere three months after the end of the TV series’ broadcast, it sparked a controversy and revealed that there was now a unbridgeable gap between two categories of creators that Urusei Yatsura had brought up to the forefront of the anime scene. The movie’s animation director and director, Tsukasa Dokite and Katsuhiko Nishijima, both claimed that their work wasn’t meant to give its viewers a headache like “Mamoru Oshii and Hayao Miyazaki’s movies”. As a reaction, Miyazaki got angry and attacked the OVA market which he deemed artistically and commercially “useless” and works where “highschool girls run around shooting a machine gun”. The carefree days of the lolicon boom were long gone, and the optimism that accompanied the rise of a “New Wave” of directors and animators seemed to have vanished: the franchise might go on, but Urusei Yatsura’s age was over.

Rumic Worlds, lolicon and doujinshi: Urusei Yatsura in fandom and otaku culture

Urusei Yatsura’s audiences

Urusei Yatsura was never the most popular anime series of its time, but it was always popular enough to remain in people’s minds and never leave it. Its rating almost never fell below the 10% bar for the 5 years of its run – an incredible feat. As a result, we can naturally assume that the show’s audience was rather wide: Urusei Yatsura was mainstream. But this, in turn, has another important consequence for us: that most of Urusei Yatsura’s audience remains invisible. Indeed, the characteristic of mainstream audiences, especially in a time before the Internet, is that they watch the show and then don’t leave traces – any discussions held between friends in classrooms, houses and cafés have vanished forever. In other words, all the documents that I’m going to discuss here are those left by already invested fans. But even then, we will quite easily note multiple levels of investment, from the casual anime magazine reader to the most hardcore Urusei Yatsura otaku.

First, we can begin with the broadest possible indicators: anime magazines’ popularity contests. Two are of interest for us here: Animedia’s top 10, and Animage’s Anime Grand Prix. The former is particularly notable, because it indicates how immediate Urusei Yatsura’s success was: the show was already ranked third in the top 10 series of the year 1981, even though it had only aired for a few months. Moreover, Animedia provided statistics and commentary on the voters, which gives an image of its reader base:

“The number of readers who voted for the best 10 anime of 1981 was 20,076. However, since each person could make three choices, the total number of votes amounted to 60,228. […] Among the 30 works nominated, the top 10 are by far the most popular, accounting for 80% of the votes. This shows that fans have become more discerning and selective about the anime they want to watch. It feels like the old days when people would just watch anime, whatever it actually was, are disappearing.”

While Animedia’s journalists were witnessing the slow development of the otaku audience, they remained somewhat outside of it. The clearest proof of this is their explanation of Lum’s popularity among both boys and girls: “Lum’s trust and devoted love for the cheater Ataru seems to embody an image of womanhood that is now fading away”. This strikingly conservative analysis had a point, in a way – it touched on the fact that Takahashi’s politics have never been revolutionary – but completely missed Lum’s role in the lolicon boom and her subversive character for both male and female viewers.

We then turn to Animage, which was also, among other things, one of the main factors in the mainstreamization of lolicon. Indeed, 1982, the second year in Urusei Yatsura’s run, was also the peak of the lolicon boom: in its April issue, the leading anime magazine included, as an extra, a “lolicon trump”, a set of playing cards with depictions of popular female anime characters – Lum and Shinobu were respectively the Jack and Queen of Spades. Two months later, Hayao Miyazaki (involuntary lead lolicon creator) sparked controversy by criticizing his most ardent fans in the pages of the same magazine and accusing them of immaturity.

Animage’s fanbase was therefore very different from Animedia’s. Looking at the 1982 Anime Grand Prix (judging 1981 works), we notice some common trends, such as the popularity of mecha and the overwhelming place shows like Goshogun and Godmars played with the female audience. But the most striking element is that the readership was far more restricted: the Grand Prix winner, Farewell Galaxy Express 999, obtained 1882 votes; to compare, Animedia’s top 1981 show, Queen Millennia, got 7086 voices (and was only in 14th place, with 263 votes, in Animage’s ranking). However, Urusei Yatsura was more popular with Animedia’s mainstream readers than Animage’s: it was ranked third in the former, and only sixth in the latter. The gendered dimension of the fandom was also far more obvious in Animage: Lum was the second most popular character overall; but, when the results were divided by gender, it painted a different picture. She was n°1 among men, with 881 votes, but only n°16 with women, only gathering 127. Finally, Urusei Yatsura triumphed in other categories: Ataru’s Toshio Furukawa obtained the second place in the voice actors ranking, while Lum no Love Song won the top spot in the opening themes category (only winning over Godmars’ opening by one vote).

As it was for TV ratings, Urusei Yatsura never obtained the first place in most categories, but it never went away either. For instance, here are the 1984 results: Only You was n°5 in the top 10 ranking and the TV series n°6; Ataru the 5th most popular male character (and Toshio Furukawa n°3 most popular male voice actor) and Lum the 2nd most popular female character (with Fumi Hirano n°4 female voice actor). The show’s second opening, Dancing Star, was n°6 in the theme songs ranking. The results of the 1986 Grand Prix are very similar: the third movie, Remember My Love, was ranked third and the TV series sixth; Ataru was n°4 and Lum n°3; as for the voice actors, Furukawa was n°4 and Hirano kept the same ranking. Notable is the appearance of Shigeru Chiba in the list, at place n°8.

Now, who were these fans? Animedia’s readers, the closest to the mainstream, were relatively evenly divided between men and women. Such was not the case for Animage’s, and for the next level of fans, those who went to events and wrote fan mail. For instance, we can take a look at the report of an event that took place in September 1982: “The fans who gathered numbered exactly 800. 80% were middle and high school boys. These happy Urusei Yatsura fans were chosen among 8000 applicants.” Later, a report from a preview of Only You notes that “as usual, 90% of the audience were boys”. In other words, the Urusei Yatsura fandom fit the profile of the otaku audience: young men with free time and progressively acquiring financial independence. There, Urusei Yatsura’s extremely long run (both the manga and anime) must have played a part: someone that was in high school at the beginning of either the manga or anime would have been in university or already working by the time they ended. The initial fandom grew up with the series and its engagements with it changed, at the same time as new fans discovered it as it went along.

Fan reactions

While Urusei Yatsura’s popularity remained somewhat constant, its fandom evolved alongside it. Judging from reviews and reactions in magazines such as Animage and Fanroad, the show reached its peak popularity between Only You and Remember My Love, that is in 1983 and 1984. In the end, it also seems that fans favored Oshii’s part rather than Yamazaki’s: for its penultimate episode, the TV series aired a ranking of the top 10 most popular episodes. 6 were from Oshii’s half, and 3 were original. The focus of their attention was the relationship between Ataru and Lum: the most popular episode, “After You’ve Gone” (storyboarded by Yamazaki) is entirely dedicated to it, as are many of the others, such as the famous “Pitter-Patter Christmas Eve”.

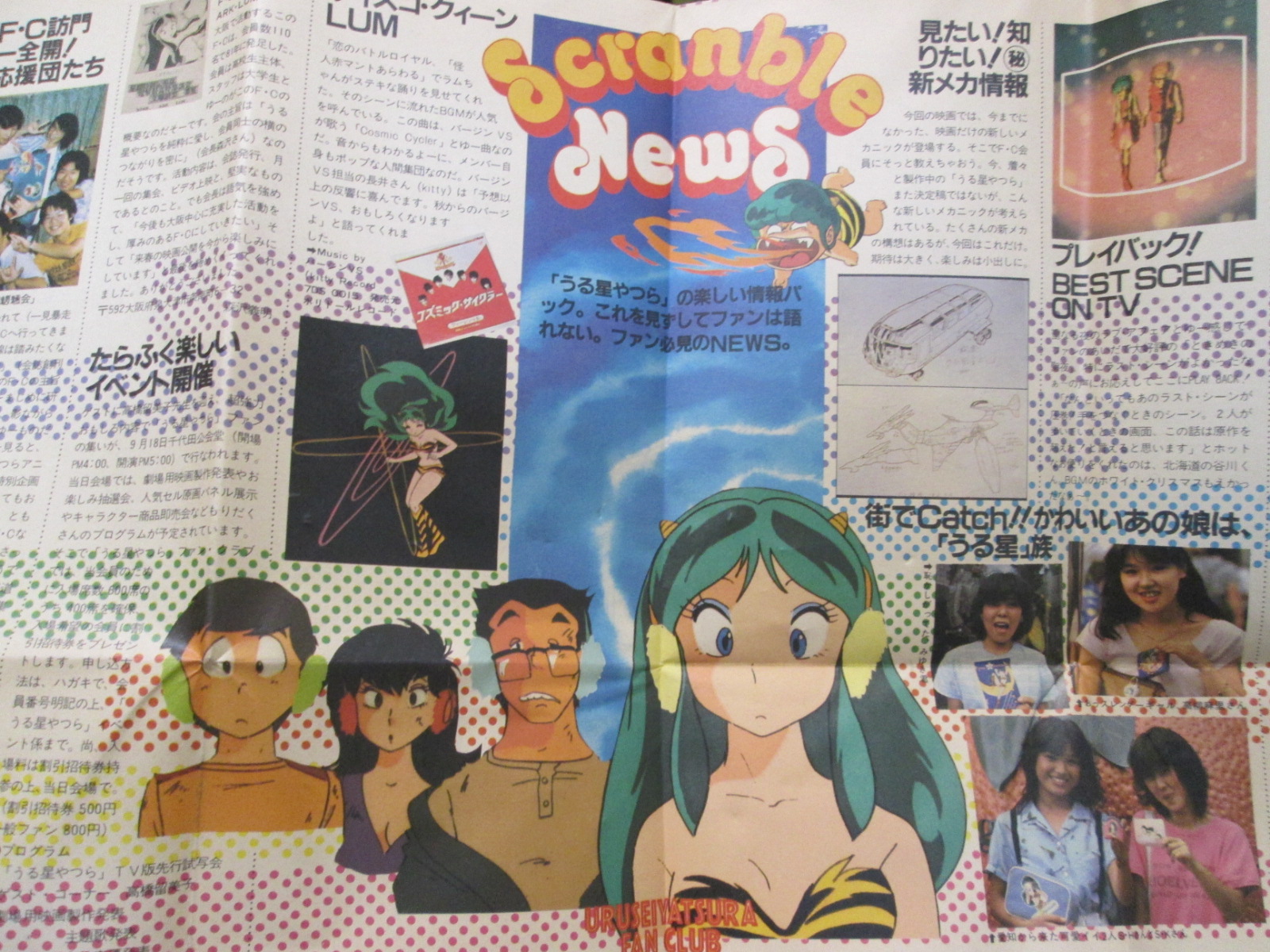

Besides such popularity polls, fans’ expressions mostly came out through fan mail and fanart, mostly published in magazines like Fanroad. The reviews and opinions there often differed from the more specialized content written by critics and published in Animage: they were informal, tongue-in-cheek, and give a totally different image of Urusei Yatsura’s reception. The most recurrent topic was the issue of adaptation: many complained when the anime strayed too far from the manga. In December 1983, Fanroad dedicated multiple pages to the “Urusei Yatsura controversy” that divided the fandom, and published a series of letters attacking or defending the anime:

“To please the people who want Lum-chan’s celluloid version to become dirty, the world has adopted a perverted image. I’ll never forgive people like this! Stop it, now! Ah! Maybe I went too far…”

“The Urusei Yatsura anime has been causing a lot of problems because it differs from the manga, but I think that animation and manga are fundamentally different things, so it’s unreasonable to ask the anime to be just like the manga. Besides, if the anime was just a copy of the manga, what would be the point of making an anime in the first place? I think that because you can look at it in two different ways, you can enjoy it twice as much (it’s not that hard, right?)”

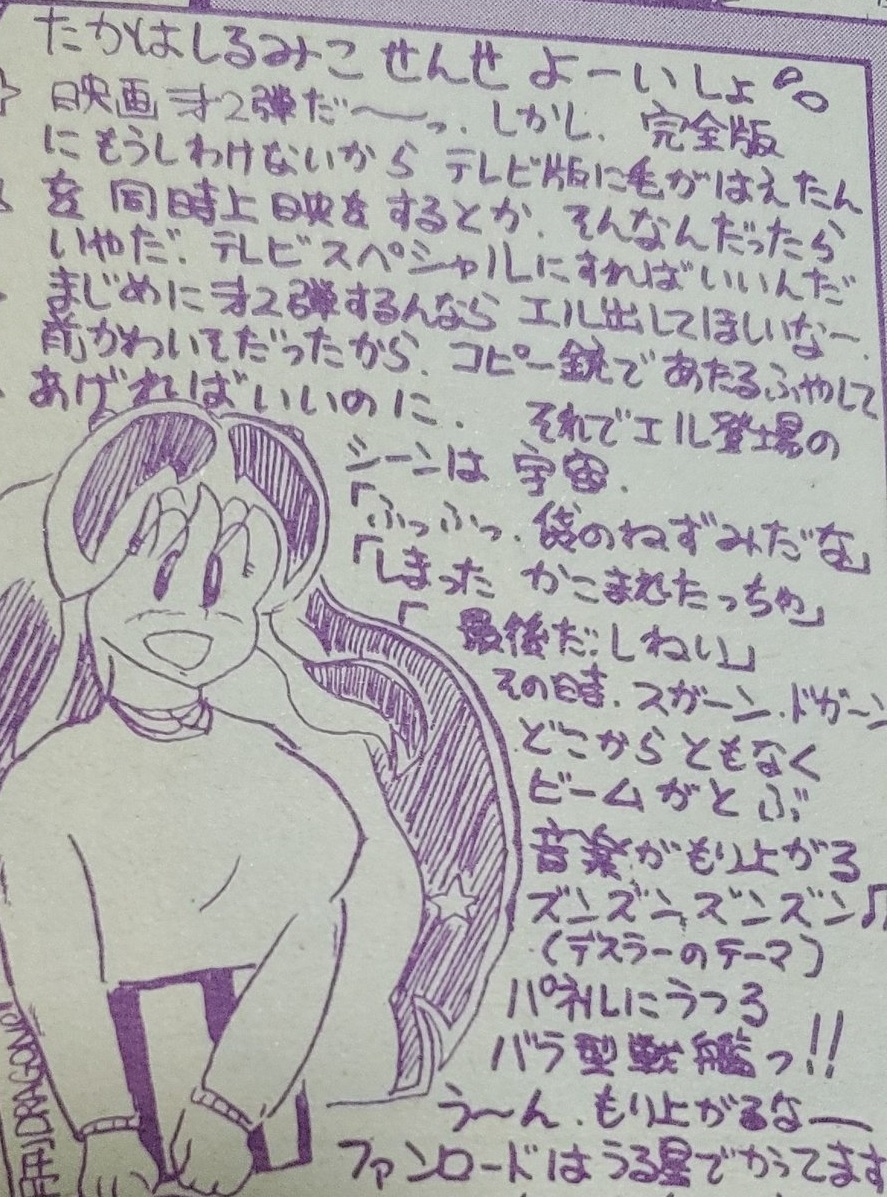

Lum fanart and a long message on Only You published in the September 1983 issue of Fanroad

A related controversy, which comes out in the first of the above quotes, was the one relating to sexuality in Urusei Yatsura and its fandom. Multiple fans, staunchly devoted to Lum, protested against her sexualization, such as “Lin”, whose message was printed in the September 1983 issue of Fanroad:

“Among the fans, there have been people defiling Lum-chan. It’s truly saddening. I’ve read in a magazine that some mangaka is making dirty parodies, that people are making dirty plastic models or games where you strip Lum-chan. This is absolutely outrageous. How dare they look at our pure Lum-chan with such dirty eyes! That makes me mad!! Lum-chan is our ideal goddess. For me, to defile Lum-chan is to be truly evil. There’s no way that people like me, who innocently love Lum-chan, can just stand by and watch. The worst is that things like that are increasing. I want them to stop. Stop it! Perversion is forbidden!!”

The tone here is so outraged and exaggerated that it might even be parodic, but it is representative of a very real debate going on in the fandom. The reverence for Lum and the systematic tendency of many fans to refer to her by the affective “Lum-chan” shows that this kind of protest is very different from, say, Miyazaki’s and other’s criticism of the lolicon movement: the person writing this was very much a lolicon as well (even though they reject the term later in the letter). This is, rather, a reaction against a movement happening in doujinshi spheres, in which the obsession with purity so characteristic of early lolicon was progressively being set aside.

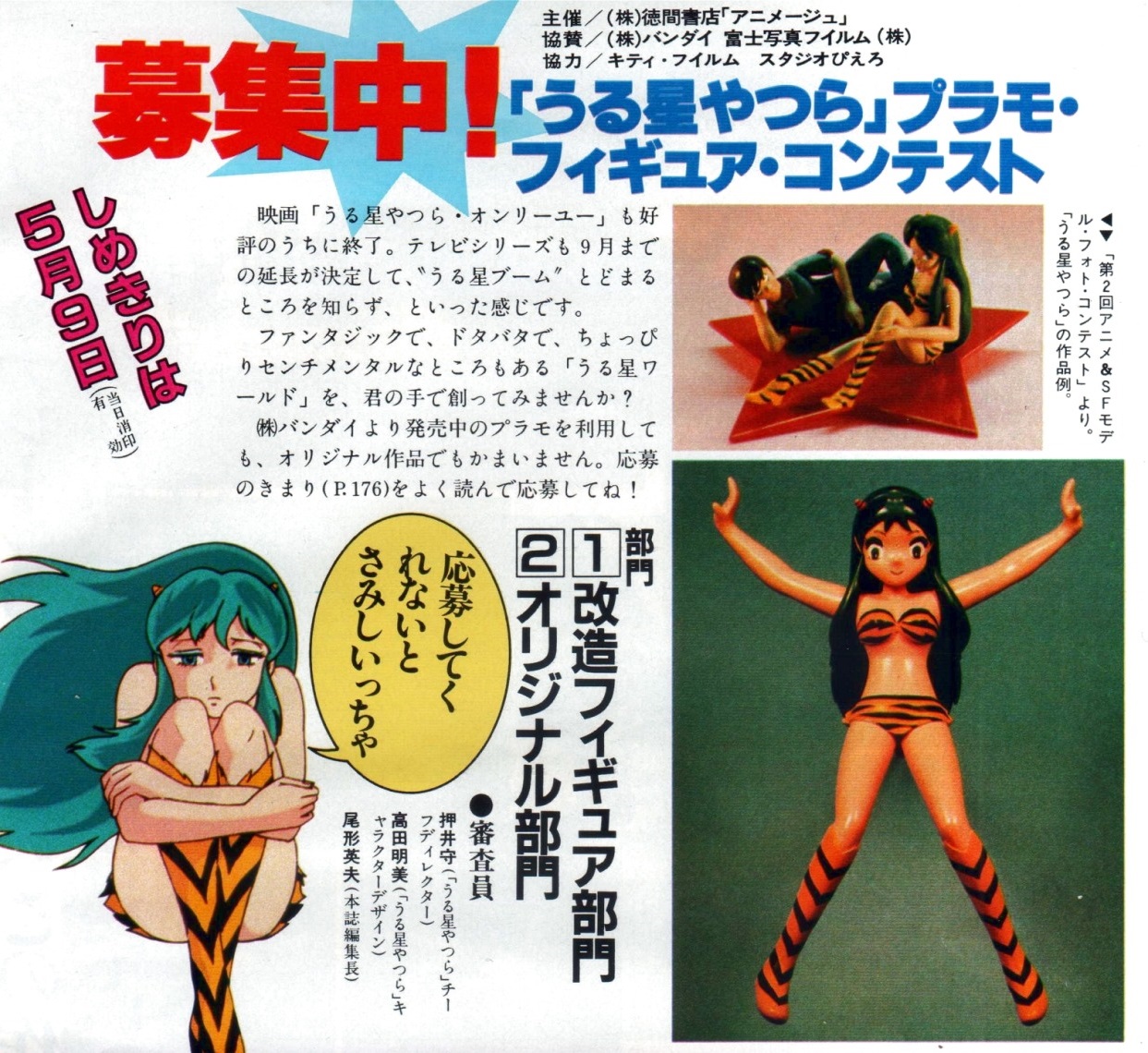

Such messages reveal multiple things: that even among Lum fans, there were many ways to apprehend, appreciate and venerate the character. But also that the range of fan activities was almost without limits: here, we have parodic manga, indie games and plastic models mentioned. These played an important part, and were often featured in anime magazines: in May 1983, Animage reported an Urusei Yatsura fan figures contest.

Another major activity was fanart. The fanart that was published in anime magazines may have overlapped with doujinshi production, but the two should be distinguished: fanart was at the same time a more solitary and public activity. Solitary, because it was made by isolated individuals, not in circles, and public, because it was published in national magazines and not read by the limited readership of the circle and its own fans. Moreover, the kind of communication was very different: fanart was safe-for-work, and often included text messages, making them just another sort of fan mail. Finally, although fanart was often the more amateurish side of the coin, techniques could be surprisingly diverse and elaborate: CGI fanart, which was still exceptional at the time, often appeared in Fanroad’s columns.

Doujinshi worlds

Doujinshi communities and circles probably represented the most hardcore section of the anime fandom. However, just like the more mainstream or casual stratas, they weren’t just one cohesive group with completely uniform tastes and practices. Before going through these, it’s necessary to mention how, in raw statistical terms, the doujinshi scene changed during Urusei Yatsura‘s run. The Comiket, Japan’s first and largest doujinshi market, experienced tremendous growth between 1981 and 1986: the number of circles went from 600 to 4,000, while the number of participants went from 9,000 to 35,000. This was fueled by multiple factors: offset printing became more affordable, making it easier to create fanzines, the Comiket moved to a new, bigger location in Harumi – but, most importantly, the growth was carried by two franchises: Urusei Yatsura among men, and Captain Tsubasa among women. Women still made up most of the Comiket’s population: according to the catalog of Comiket 29 (December 1985), the number of circles presided by women was 1.7 times higher than those presided by men. Still, the number of men was slowly rising. Additionally, circle members’ mean age at the time was 20 years old – mostly university students.

To return to Urusei Yatsura fans more specifically, their doujinshi production could be generally broken down into three categories, which I’ll cover one by one.

The first is Rumiko Takahashi fans. Their production had two characteristics: it was not systematically erotic or pornographic, and Urusei Yatsura took as much as place as Maison Ikkoku and Takahashi’s other, shorter works. Contents would usually include fanart and manga, often with Urusei Yatsura/Ikkoku crossovers and essays on various topics, such as “Is Urusei Yatsura a love comedy?” Although mostly related to the manga, some would also cover the anime with plot summaries of the films and reviews. I am going to extensively cite part of one of these doujinshi, Jipang #6, published by the circle HCIA. Dating from March 1983, it is quite a fascinating document that retraces the circle’s history:

“July 1981. On his way to see Mobile Suit Gundam II: Soldiers of Sorrow, A bought Big Comic Spirits. Upon reading Maison Ikkoku, A’s Rumic was invoked (just like the will of the Ide?) and he was pulled into the Rumic World.

October 1981. Completely taken in by the Rumic World, A resolved to make more victims. The ones who ran into such a pitiable fate were O and K. The Urusei Yatsura anime version had just started, and O and K witnessed their Rumic being invoked as well.

January 1982. Having come into contact with Rumic, A, K and O finally formed the Rumiko Takahashi Fan Club “HCIA”. At the time, the team was made up of President K, General Secretary O and Treasurer A. Two other members were forced to join, amounting to a total number of 5 members. […]

April 1982. Absolutely impossible to gather any members. A and K disagreed about the course of action to follow, and conflict ensued. At this point, a coup d’état took place, and Treasurer A became the second President, while K was demoted to Vice-President. This was the beginning of the HCIA Warring States period. […]

August 1st, 1982. Participated in the 14th edition of the Mini-Comic Fair under the rain. Encounter with the T.S.P. (Tiger Striped Pegasus).

August 8, 1982. Participated in the 21st Comic Market. A treaty of friendship with the T.S.P. is concluded. The number of members exceeds 30.

September 5, 1982. The “Ochanomizu Conference” ends in failure (we were just trying to create a confederation of Rumiko Takahashi Fan Clubs…). […]

October 10, 1982. On the date of Rumiko Takahashi’s birthday, attended the “Ochanomizu Summit” (a summit conference between the members of various Rumiko Takahashi Fan Clubs). A treaty of friendship with the U&R (Urusei & Rumiko Fan Club) is concluded. Around this time, the HCIA progressed into the physics department of CS University. The question remains whether this was a “progress” or an “invasion”. The same month, the number of members passed 100. […]

February 1983. At an academic conference, the theory that the HCIA is a living organism sucking out the lifeforce of healthy young men is submitted. […] That month, the number of members reaches 130. The current number of members is approximately 140.”

The highly ironic, self-deprecating tone is very typical of doujinshi production, and just this makes this chronology a valuable document on otaku’s self-perception. But it also teaches us a lot about the social dynamics of otaku and doujinshi circles: HCIA’s growth was rather fast, and all the friendly competition with a huge variety of other fan clubs is very indicative of the atmosphere of the time. Moreover, the mention of the fan club “progressing into” a university provides some insight about the age of its members: in their early to mid-20s. There is sadly no indication relating to their gender, but as indicated earlier, most of them were probably men. We also get a good idea of how dynamic the scene was, with a huge variety of circles and events happening all year. Animage‘s “Circles List” column paints a similar picture: new circles and fanclubs were emerging all the time all across the country.

Finally, although it may be important to distinguish between the two categories, it is apparent that the person who wrote that text was not just a Takahashi fan: the Gundam and Ideon references make it clear that they were a general anime otaku. This brings us to the second class of doujinshi, perhaps the most important relating to Urusei Yatsura: those produced by anime fans. Here, we move from fanart and essays to erotic and pornographic content. Many doujinshi, especially those published after 1984, would almost never exclusively feature Urusei Yatsura’s characters, but also those from the other popular anime of the time: Minky Momo, Creamy Mami, Zeta Gundam…

Besides all the aforementioned demographic elements, Urusei Yatsura and the doujinshi production it triggered had a major impact in the kind of content that would be created and published. According to critics, Urusei Yatsura doujinshi represented a third major step in doujinshi history. The first generation of creators, those that created the Comiket in the mid-1970s, were mostly women and produced Boy’s Love content, either derived from BL shôjo manga or popular mecha series such as the Robot Romance Trilogy or, in the early 1980s, series like Godmars. Then, from the publication of the Cybele magazine in April 1979, male lolicon artists arrived on the scene and started challenging the status quo at the Comiket: they reappropriated shôjo culture, but by men and for men. Then, from 1981-1982 onwards, Rumiko Takahashi-inspired content created a new movement. The appeal of Takahashi’s work was explained by a critic in the late 1980s:

“Both Urusei Yatsura and Maison Ikkoku are sexual love comedies that make a point of not crossing a certain line. Their heroines, Lum and Kyôko, are young girls (women) who have physically glamorous bodies, and psychologically keep their chastity for one single man. For people making pornographic parodies, this is the best kind of target to profane (that is to violate). Furthermore, in both productions, these two aren’t the only bishôjo characters: there is a wide variety such as Shinobu, Sakura, Ryûnosuke…”

In other words, Urusei Yatsura had created a very specific, unprecedented balance: it was, in a way, a harem series, in which women surrounded a male protagonist and in which sex has a very concrete existence; but the female characters kept their purity and chastity. It is notable that one of elements that supposedly made Urusei Yatsura open to the mainstream – Lum’s eroticism not being “dirty” – was also what attracted the most hardcore, fetishistic part of the fandom. In any case, this balance was completely different from previous lolicon-favorite works, in which sex simply didn’t exist (Angie Girl) or in which girls had to be protected from sex (The Castle of Cagliostro). Azuma and Cybele-inspired lolicon works were transgressive because they were erotic or pornographic, but they also maintained and “protected” the purity of their girl protagonists by putting them in situations where they weren’t confronted with men or heterosexual relationships. Urusei Yatsura and Maison Ikkoku doujinshi broke that barrier and opened the gates of more “conventional” (ie heterosexual), but also more graphic sex. And indeed, when one compares the eerie fetishism of Hideo Azuma’s work of the late 1970s to a hardcore tentacle rape Urusei Yatsura doujinshi from the mid-1980s, there is almost nothing in common.