Ken’ichi Yoshida may be one of the greatest character designers of the last decades. Debuting at studio Ghibli in the late 1990’s, he went freelance in the early 2000’s and became one of the closest colleagues of legendary director Yoshiyuki Tomino on Overman King Gainer and Mobile Suit Gundam: Reconguista in G, as well as character designer for the Eureka Seven series. His characters are extremely recognizable for their elegant, flowing lines and delicate features and have earned him the nickname “God”.

Most recently, he has been working alongside yet another legend, animator and director Mitsuo Iso, on the latter’s new work, The Orbital Children. Putting to full use his talent as a designer and his experience on SF works, Yoshida changed his approach once again, adapting his unique sensibility to Iso’s.

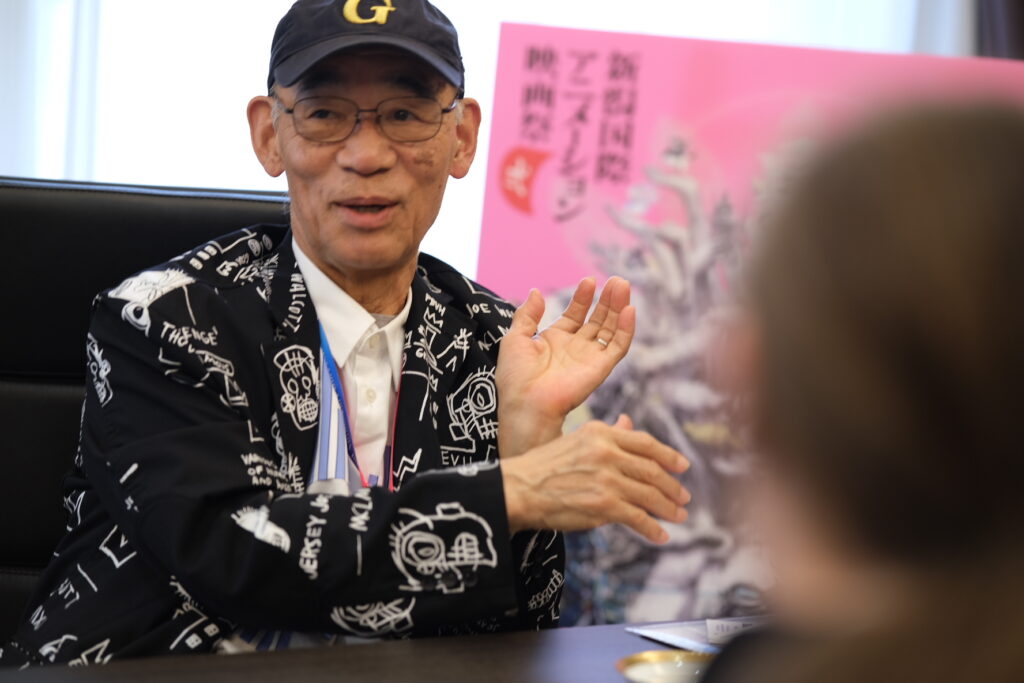

After a brief encounter with Mr. Iso himself at the Niigata International Animation Film Festival, we had the opportunity to visit studio +h, where The Orbital Children was produced. There, we enjoyed more than an hour of discussion with Mr. Yoshida, where he told us all about The Orbital Children’s production and the secrets of his style.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

“Iso was like the frontrunner of our generation”

Could you tell us how you met Mr. Iso ?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: It was at Ghibli, at the time of Kiki’s Delivery Service, when the studio was hiring new graduates. Back then I was in my second year of vocational school and starting to look for work, so I applied thinking it’d be a good way to test my skills, and luckily I got hired. Masashi Andô[1] also got hired at the same time.

Together, we would talk about things like movement in new anime, and there was this young animator sitting at the desk behind us. One day we happened to arrive first at the studio, so we went to check out our colleagues’ desks. There, left on Iso’s desk, were thumbnails, drawings of the successive steps of a movement. And we were both kinda shocked, and talking about how good they were. So in a way, we were in contact with Iso right after we got in Ghibli. Later, we became key animators, and Iso happened to be sitting just behind me and next to Andô, so we talked to him quite a lot. From time to time, we’d ask him, like, “How do you do this, or that?”, he really helped us. So, well, that’s how our relationship with Iso started.

Were you friends at the beginning ? Or more like rivals ?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Both Andô and I got to know Iso back when we were still in-betweeners, and among the things we saw and used to train and improve, there was his work. We quickly realized how good he was, so there was no rivalry, he was more like a mentor to us. He wasn’t actually much older than us, only two or three years. That too, was a shock: someone only three years older than us was already capable of such things. In that sense, I’d say Iso was like the frontrunner of our generation.

Of course, Iso’s an amazing animator, but when did you feel that he also had the potential to be a director ?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Probably from the very beginning. For instance, when talking things over with Mr. Miyazaki, like how to approach this or that scene, he wouldn’t only discuss the movement or acting, but he also considered how it would play into the movie as a whole. Also, the way he’d say what he had in mind to the producers. So I already felt that he would make it as a director. Also, he was an idea man. So he both had ideas and wanted to make them real.

After that, how did you end up being involved in Dennô Coil ?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Iso was already working on Dennô Coil back when we were doing Eureka Seven (laughs). Roughly a year after Eureka stopped airing, Dennô Coil started. I was watching it too, and near the end, I got a phone call asking me to do key animation.

Before Dennô Coil, Iso had offered me to work on RahXephon, his debut as episode director. Actually, he thought it was an offer to make Dennô Coil back then… Anyways, it already looked interesting back then, but when he called me Iso went like “Say, I did take care of you a while ago, right ?” (laughs). I said something like “Yes, thank you again for your help”, and he went on and said “I’d like to talk to you about something, you wanna get a coffee ?”. And so he asked me if I wanted in on his project, but at the time I was working on OVERMAN King Gainer with Mr. Tomino[2]. Broadcast hadn’t started yet, but since I was about to refuse, I thought I might as well bring the materials from Gainer. So I did that and told him I was busy with that, so I couldn’t help, things were tough for me too, that kind of thing… Apparently he mistakenly thought that I was trying to show off. (laughs)

So later, I did have a debt towards Iso, so I decided to help on Dennô Coil when it was in trouble. I thought that since it was the end of the show, I could be of some use. There’s always a bunch of talented people on the first episodes, but I knew very well that the end of a TV show is the most difficult part, so I figured I could help a bit.

“Approaching things as half-lies and half-truth is what my job is all about”

For The Orbital Children, you were the one to choose that project among the 14 that Mr. Iso had shown you. Why did you make that choice?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Well, I had been working on stories about space before, like Gundam: Reconguista in G… But above all I feel like people, not only in Japan but all over the world, are wondering if there is a need to go to space. With the construction of stations like the ISS, which has welcomed several Japanese astronauts, people are starting to get accustomed to images of space, and what everyday life there is like. But it’s no longer possible to realistically imagine making such a life part of man’s domain, to push the boundaries of the world like SF used to. On the contrary, I kinda feel like everyone has come to realize that life in space is impossible. So, by doing this, I’m sort of drifting away from everyone’s choice.

But the way I see it, we can’t know for sure if it’s possible to live in space until we’ve tried it, right ? I don’t know how difficult it actually is, but there’s probably a way to achieve it, or if we can’t live in space, maybe at least go to space, stay in contact with space. Keeping this up surely will push man’s knowledge further and further, and somehow I get the feeling that stopping it could only lead to bad things. That’s why I have to continue making space-related anime : to foster people’s interest in the subject, to make them think it’s okay to go to space. But then as I work on that, I realize that… well, it’s about children more than other people, adults are no good. I’m convinced that adults can’t go into space anymore (laughs).

But children, if they can, they’ll genuinely want to go. That’s why I think it’s important to spread these sorts of resources to the world, and for someone working in animation, it’s a pretty decent job. It’s for those reasons that out of all of Iso’s projects, I chose the one with people going into space.

Mr. Iso doesn’t want The Orbital Children to be considered SF, but for us viewers, it sure looks like really well-done hard SF. What’s your opinion?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: If we just called it science-fiction, people would end up putting it in that category and not see it any other way, so it seems better to present it to children as a modest depiction of space. This way their imagination isn’t limited by things like SF or science. In a lot of ways, it’s best if they perceive the series as its own universe, so I think that’s why the director was so concerned with not using science-fiction, as a category, to describe it.

Like, depending on people, it might be thought of as fantasy, science-fiction, or space fantasy, right? Still, this world was made to be half-real, integrating realistic elements while simultaneously making up lies. How do I say this… To reach reality, you have to put in some of the lies specific to animation. You make up the story by putting in things that couldn’t actually exist, and I feel that if people like this story, they’ll probably take an interest in space, right ? But I might have been a bit obsessed with those things…

The science behind the series looks really serious, but did you do any research yourself?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Well, I like science… but it’s not really my forte. It’s Iso who’s very good at these things. He really has a scientific mind, while I, if I had to say, would be more of a space fantasy type person, one who likes the lies in a story. That’s why I’d describe myself as an SF fan who’s bad at science. There are also people like that, you know! (laughs) I want to understand, but when I try, I just can’t. But still, I think I’m interested in things like how stars work or how nebulas are formed more than most people… Yeah, I like these sorts of things.

As you were creating the world, how were the discussions between you and Mr. Iso? Did you have a lot of initiative?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Hm, the first thing we discussed was of course the characters. Then, well, the general setting, and specifically space suits, like with this “Oniqlo” brand. I didn’t design them thinking about how they related to the world as scientific devices, but rather about how they could visually differ from space suits seen in earlier space-themed productions. As a designer, I tend to follow some patterns, right? In addition, there are the real space suits used by the Soviets or Americans, and those used in SF works like 2001 or Gundam. I was looking for a way to design something different from all those, while making something that might actually exist in the future. And so in the end, I found that something like this parka (he shows the parka he’s wearing) might be a good compromise, visually speaking. I thought in a way, the parka kinda looked like an extension of clothes, so I added a life-support system.

(Browsing through the production materials, showing the spacesuits) Ah, you mean these, right?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Yes, those, the design is really fifty-fifty. When I showed the first drafts to Iso, he said things like “It still feels a bit like Gundam”, or “It’s a little too serious”, “Let’s make it lighter” etc. So as it went, my proposals drifted further and further away from pre-existing space suits. In the end, I obtained this look that feels like it could or couldn’t actually exist.

There are the same gloves in SpaceX’s suits: they have this way of taking them out with a zipper. When Iso saw that, he was really impressed, so we decided to include it midway through the design process. It’s a real issue: once you take out your gloves, what do you do with them?

On The Orbital Children though, I tried to make the designs simple: when you take it off, the suit floats back behind like it’s made of rubber or something like that. The top now completely looks like a jumpsuit, but made out of a more elastic material. Even if it’s fake, as long as we make drawings of it, it feels like maybe someone might make that in the future. (laughs) I think approaching things as half-lies and half-truth is what my job is all about.

Was The Orbital Children’s preproduction very different from the preproductions of King Gainer and G-Reco, which are also SF? What’s the difference between Mr. Iso and Mr. Tomino?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Tomino’s concept ideas are much vaguer, like with that zipper thing on the spacesuits. He’d just say “I’d like to try something with a zipper”, or “I want to put toilets in the cockpit”, and then “so, make designs for it”. And I’d get back to him with sketches to check if it was what he had in mind.

On the other hand, Iso’s originally an animator, so he often begins with drawings. Not that Tomino never does, but whenever I work with him, I don’t have to study his pictures and copy them: rather, I have to draw something completely different (laughs). I sketch a new model from scratch, and I draw a design that will feel fresh and good-looking to the audience. In Iso’s case, he draws his own pictures and I really use them as a guide.

The Orbital Children’s designs do look like Dennô Coil’s. Mr Iso’s influence is really visible.

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Absolutely. Talking from the perspective of Iso’s individual style, Dennô Coil really started from his drawings. For The Orbital Children, I didn’t want to overwrite Iso’s pictures with my own, so instead I looked for a way to expand upon his style. But it felt impossible for Tôya: there’s nothing of my style in his design. The eyes are really Iso’s trademark, and I couldn’t draw those. With the rest of the characters, I tried not to stick too much to his drawings, to take some liberties with the designs. So when working with Mr. Tomino, once I’m aligned with what he wants, I have a lot of liberty. But when working with Iso, I have to keep his style in mind throughout the entire process.

So would you say that, as a director, Mr. Iso is the same type as Mr. Miyazaki?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Well, each director is his own type, and ultimately each director has a specific way of conducting drama, of telling a story. All of them differ in that sense. In Miyazaki’s case, he controls things visually from the storyboard. And then he corrects things from his position as director. If there’s anything wrong in the acting, he corrects it on the spot. Only then does he leave the rest to the animation director. So I’d say he controls things as drawings.

In Iso’s case, he doesn’t control the drawings all that much. He’s more at the level of photography and animation, at the same time. Of course, he can’t correct every single drawing, so he tries to leave the animation to the animators, and then concentrates on controlling what comes after that.

So in that sense, maybe he’s closer to Mr. Tomino or Mr. Takahata.

Mr. Iso has a very strict image, but how is he actually?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: I actually find him to be quite kind. Or rather, since he divides the task between us, I feel like he doesn’t want to say things that might confuse me. He’s a very considerate person, in that sense. He’s not merciless with us animators like Mr. Miyazaki.

Iso takes a lot of things on himself, so he asks people to do what they can with the animation and keeps a rather low profile.

I have my own agenda, so he just asks me to do the most I can outside of that, and keeps a rather low profile. Sometimes it even makes me feel bad because some things would actually look better if Iso had drawn them.

“The only thing I knew about anime was the animators”

I feel like your designs have changed over the years. The bodies have become thinner, the lines more curved… Could you tell us about that evolution in your style ?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: There was a time where the bodies I drew got really thin. It started right after the end of Eureka Seven, and eventually that reached a point where even I started to think it was too much (laughs). Looking back at those designs, they were definitely too thin. So after that time, I got back to drawing characters that were a bit fleshier.

On Reconguista in G, they were actually a little thin, but Tomino immediately said “They’re all skin and bones, I don’t like it”, and well, they did look like they weren’t eating enough, so I… made them eat again, sort of, and that’s why in the series they look fleshy enough.

But at the time of Eureka… you see, there’s some kind of a battle between those two parts of me. One wants to simplify the designs, while the other wants to, how to say… make them more realistic. And I feel that depending on the work, one part or the other might come out more strongly than the other.

Q : When you left Studio Ghibli, did you try to leave the “Ghibli style” behind as well ?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Absolutely!

At first, your designs felt somehow reminiscent of Tomonori Kogawa’s[3].

Ken’ichi Yoshida: I started drawing characters when I was in middle school, you see. Before, I only drew robots, cars… all sorts of machines, I wanted to become a mecha animator. I admired people like Ichirô Itano [4] and Yoshinori Kanada[5]. All I thought about was drawing missile circuses. But then I came across Yoshikazu Yasuhiko’s [6] animation, who could draw both characters and mechas, and he was good at both. In fact he had to. As I thought about that, I wondered how he did it, and decided to try and copy the style of some animator or mangaka so I could improve.

So, well, I began with Rumiko Takahashi [7]. I would rather make incredible full copies of her drawings over things like Nausicaa. So I drew Urusei Yatsura or Maison Ikkoku over and over again, and started to memorize the way the characters were drawn. And even after I tried to consciously change that, there was one feature that stayed : the small-sized torso. You know how Rumiko Takahashi’s characters have very long legs and small upper bodies? All the figures she draws, whether they’d be feminine or big-headed, they always have a small body, or they kinda feel like they’re running, somehow.

But then, when I was working with Shigeto Koyama[8], he drew characters with longer torsos, because according to him it was more erotic this way. And thinking about it, it’s true that Takahashi’s art isn’t exactly “erotic”, and as a result neither was mine. So from this point onwards I decided to draw the upper body a little bigger.

Originally though, before I started copying Yasuhiko or Ghibli’s – or rather Miyazaki’s – style, when I was still imitating Rumiko Takahashi, my other model was Tomonori Kogawa. I found his art to have a clear logic to it, making it easy to mimic, so at the time I sort of tried to combine the style of the both of them. And… that’s where Katsuhirô Ôtomo steps in ! (laughs) So… those three truly became the cornerstones of my early style.

Then I joined Ghibli, and alongside Miyazaki I corrected those tendencies. But as I was getting accustomed to his style, what really felt the most stimulating to me was Katsuya Kondô’s[9] art. Looking at his paintings or Kiki’s Delivery Service’s image boards, I would always find them so cool and I wanted to do the same. I thought if Ghibli embraced this sort of more urban line, its style might evolve. So I was trying to put everything I’d learned to use to aim for something like that.

I worked ten years at Ghibli, so naturally, style-wise, a lot of things happen, as I met numerous talented people like Yoshifumi Kondô and was able to look at their work. But most importantly, I became friends with Andô. Andô basically did the same things I did, but he was extremely talented at assimilating new stuff, so to me he became a model. I spent ten years observing the way he did that, trying to apply an “Andô filter” to all that I’d learned studying Yasuhiko and others. (laughs)

In addition, Akira Yasuda’s designs on Turn A Gundam – he also worked on King Gainer later, but it was on Turn A that it showed the most – felt closer to the Ghibli line than to what Gundam used to look like before, so I wondered if I could pull that off, but drawing it… it was a little different. That’s why I thought I needed to adapt to a variety of styles, and take a fresh new look at my own drawings. Especially on King Gainer, there was kind of a gap between what I’d found good up until then and what the other designers thought to be interesting. There were a lot of different people working on the series, and although we were all in the same line of work, some were animators, while others came from design or game design, or even manga. Being able to experience design from such different viewpoints was what allowed me to “leave the Ghibli style behind”, as you said earlier.

But I didn’t want to completely erase that influence either. My idea was to sort of mimic most of what I did at Ghibli, while insisting on the differences so that it wouldn’t be apparent. To do so I used all sorts of resources, even Osamu Tezuka. In a way, you could say that it’s all coming back to Tezuka. (laughs) I mean that, in the end, all our styles take roots in Tezuka’s, no one can escape his influence. Somehow, I feel that eroticism itself, as we know it in today’s manga, with all its sex-related content and appeal, existed in his work, and even originated from it. Out of all of Japan’s “adult” art, Tezuka’s is the strongest, and the one that has remained vivid in our minds. And as that culture is now being exported worldwide, Japan has been passing laws to regulate such content, arguing that it’s unhealthy for children, things like that. I’m pretty sure this is still going on. Honestly, if you’re going to say that, you might as well forbid Osamu Tezuka altogether, you know what I mean? Tezuka’s a god, so why are we, his spiritual children, no good? I can’t understand that. But well, the fact that people all over the world are now being invaded by his legacy is really exciting.

Well, now it’s become art, hasn’t it?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Yes, yes, somehow I feel like people from around the world are starting to embrace it… I’m getting off track here, right ? (laughs)

Well, then let’s get back on it: between Mr. Yasuhiko and Mr. Kogawa, who would you say is your favorite – if it’s possible to choose?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Hm… I like both… that’s really difficult ! Truth is, when I was still a key animator at Ghibli, before I got involved with Tomino on Reconguista in G, I had a rather Kogawa-like logic. But at some point I realized that I could use both Yasuhiko’s and Miyazaki’s styles, because actually they’re quite similar, or at least their logic is. Understanding this, I was able to combine what I’d learned from both of them, and I used that when working with Tomino.

So from this point on, my logic was more akin to Yasuhiko’s than Kogawa’s. I found this Yasuhiko-like mindset to be more enjoyable, and my drawings also seemed to come out stronger. But then on The Orbital Children, I think I drifted away from it a bit. Actually, on some level, I got closer to a Miyazaki-like logic.

For Iso and I, Miyazaki’s work on Future Boy Conan [10] or Marco [11] is fundamental, even more than Yasuhiko.

So you’ve liked anime since childhood, right? And you got to work with Takahata and Miyazaki whom you admire, and then with Mr. Tomino, of whom you’re also a fan. Could your entire career be the realization of your childhood dreams?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Dreams, uh? Well, right when the Gundam movies hit the theaters in Japan, you were starting to see kids saying that they’d be animators when they grew up, and… so did I. That’s the story of how in my sixth year of elementary school, I decided to become an animator. Reason was, at that time, the only thing I knew about anime was the animators. I was interested in how animation was made, and it was with Gundam that I got to understand it, thanks to Yasuhiko’s key animation work being compiled and sold as books. It was even before Miyazaki and others were featured in such books. Looking at those drawings, I could see how animation worked.

And that was all in elementary school ?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Yes, all in my last year.

Wow, that’s amazing! (laughs)

Ken’ichi Yoshida: But you know, it was the same for everybody. I’m digressing a little bit from that “dream” question, but just after that, still in that very same year of elementary school, there was this magazine called Animage, you know, and Toshio Suzuki did the editing. In the middle of the Gundam craze, he did a special issue on Miyazaki, and there was the storyboard of Conan’s first episode included as a bonus, in the form of a booklet with an illustration by Miyazaki on the cover.

My elder sister also liked manga and anime, so she bought that issue, and I read that storyboard again and again. Along with Yasuhiko’s key animation book, this storyboard allowed for a better understanding of the animation making process. In this regard, Animage and people like Ryûsuke Hikawa [12], who created such occasions, were truly epoch-making.

Hikawa was the one who put together that Yasuhiko mook with the key frames. He didn’t make copies, instead he took pictures of them himself and put those pictures in the book, so you could see the fleshy dimension of the drawings. You could say we were seeing Yasuhiko’s actual key frames. About a year later I think, other mooks on the likes of Katsuhirô Ôtomo were released, and in the span of two or three years, a whole lot of these had come out. So people like Iso, Kimura, also Hideaki Anno’s generation, they probably all read that like crazy… And they all turned out to be… quite the characters, didn’t they ? (laughs) There’s also Shin’ya Ôhira, Osamu Tanabe… that generation of animators spanning over three or four years is really the most obsessive, I think. Toshiyuki Inoue[13] is a little older, he’s from the “Conan generation”, so to speak, but anyway, there’re a lot of troublemakers in this batch, and I’m at the bottom of that list.

“Once Inoue’s in the ring, it’s like you’ve already lost”

Speaking of Toshiyuki Inoue, we interviewed him about The Orbital Children, and he spoke very highly of you. He said you were the next Yoshikazu Yasuhiko, or the next Akio Sugino[14]!

Ken’ichi Yoshida: I’m very happy to hear it! (laughs)

If I had to say, I’m probably closer to Yasuhiko, and Andô would be closer to Sugino. Though we’ve basically been watching the same things, Andô really has a lot of respect for Sugino. When I saw his characters for Paprika, I immediately thought of Sugino. Same goes for his more recent Deer King, the characters all have a sense of humanity, a vitality to them that reminds me of Sugino. That’s something Andô always puts in his work. And in Paprika, you can really see the same thing as in Sugino’s latter half of his career: they look alive, but also like dolls, in a way… Though that might sound weird.

You mean like in Dear Brother, for instance ?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Right, like in Dear Brother. Paprika feels really close to that feeling, even down to the worldbuilding. The Deer King on the other hand leans more towards feeling alive, I think.

So while Andô works around this, when it comes to my work, I’d say it’s closer to Gundam – if that makes any sense – and therefore to Yasuhiko, whose influence comes out stronger. So… well, as for being compared to Yasuhiko and Sugino… those who know, know, right? (laughs) And Inoue sure can tell who’s behind a picture.

Where do you think Mr. Inoue himself stands?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: You know, about Inoue, I think you can only understand him once you’ve worked with him. You probably know that he draws very fast, but I don’t think you can understand how fast exactly. I don’t even get it myself… What I can say is that I don’t think time works the same way for us both, because no matter how fast I draw, he’ll always be way faster than me. I couldn’t even imagine drawing that fast, even working without a worry, so I just came to wonder if maybe he was working on a different plane from the rest of us. Like he’s in the metaverse. Or he’s resting his body and soul in a different dimension while working in this one, or he’s working simultaneously in several dimensions… I don’t know, something of that caliber, at least.

I brought up this theory when talking with Iso, and ended up on a World War I metaphor. There was this British tank, you see, the Mark I. Well, the difference between us and Inoue measures the same as a footsoldier, or even a footsoldier in a dugout, standing in front of a Mark I. If you pictured Inoue as that Mark I, you’d get a good idea of him, I think. To explain it with Gundam, it’d be like facing three Big-Zams. Nobody would stand a chance. Even Amuro would be in trouble !

It would be unfair, at this point! (laughs)

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Zeon would definitely win! Once Inoue’s in the ring, it’s like you’ve already lost !

I wonder if there’s anyone who can catch up with him. They’d have to be on Miyazaki or Yasuhiko’s level. As a key animator, not only does he shine through his talent and speed, he also takes into account the directorial intent of the scene. Because he can read it, he’s able to stay true to it. Even among talented people, that’s rare. You’ll get a lot of “That’s really good, but it’s a bit different from what I wanted”, which hardly ever happens to him. He himself says he simply draws what he’s familiar with, and I would think that’s how he got to such a level of familiarity with drawing. I wish I was able to get to that level too… but it’s downright impossible. People who can manage to get there, though… that’s who we call “legends”, right ? Inoue refuses the title, but most people could never accomplish what he does. Because he’s so fast and so good at his job, I got people telling me I should learn from him, but I’d never listen to someone saying that. It’s like telling me to copy Miyazaki: it’s just impossible, and discussing it is pointless, nobody should do it. It’s to the point where you’d be a bad person for simply mentioning it. Naturally, at the moment in Japan, there aren’t a lot of people who can aspire to such a level. Lately, a lot of fast animators are turning up, but I believe the reason to be the direct influence of Inoue.

“I think I’ve successfully sown Miyazaki’s seeds around”

Moving on to your next projects, wouldn’t you like to try out directing?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: I feel like if I were to do that, I would’ve already done it. I never really felt like directing, so I never did. In my opinion directors should be people who actually want to be directors. That way they can’t complain, because they were the ones who asked for it! (laughs)

As for me, I like to stand beside such directors, and contribute to their work by giving them ideas on this or that. Although doing so kind of makes me sound like a director. But in any case, I want to stay in a position where I can continue to draw. And being a director… Well there are directors who do it anyway, but I fear that being in this position won’t allow me to draw as much as before. Like I’m pretty sure Iso would be happy to do more drawing. But in the case of a TV series, especially one with many episodes, of course it proves difficult. There’s also one more thing : I’ve watched many directors at work, but in the end I feel that the one most arduous part of the job might very well be doing what you actually want to. That’s why being a director seems to me like a really hard job, and if possible I’d like to stay clear of it for the time being. But maybe that will come to change in the future, I don’t know yet.

If the opportunity came, what would you like to do?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: That’s a good question… Maybe something with robots ? I’d like to make a work that looks like it’s for children, but in fact depicts how people live and die – however dramatic that may sound. All the works I love are like that. They’re all made for children, but actually speak to them in an adult tone.

That’s also the case of The Orbital Children, isn’t it?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Yes, I think that does apply to The Orbital Children. It doesn’t underestimate or look down on children, but instead treats them like any other humans. If I could, I’d like to make such a work.

Though that’s pretty vague. But I honestly don’t know if I’d rather do SF, robots, magical girls, adventure or children stories. What I do know is that it would be a coming-of-age kind of work. Visually, it would have to be appealing to ordinary kids. It’d be great if people who aren’t usually interested in anime could appreciate it. But on the other hand I’d also want people who love anime to appreciate it too… I guess that makes me a bit greedy, but that’s what I’ve been striving for as a character designer until now. That thin line where you can appeal both to people who like anime and people who don’t really care for it. People like Yasuhiko, Kogawa or Miyazaki all walk that line. Iso as well. The key, I think, is to be able to create characters that are cute, or beautiful, while also looking natural. I always try to include both those characteristics in my designs, much like Katsuya Kondô does.

By the way, do you have any news from Miyazaki’s next film?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Actually, there’s a cafe I often go to and sometimes I meet Miyazaki there (laughs).

Even after I’d quit Ghibli, I used to meet up with him quite a lot at that place. Or rather, we’d meet by accident and chat a little. As always, he isn’t one to look back, he can only see forward, so once this project is over, he’ll probably be thinking of a new one already, and talk only about that. I’d say he’s still got plenty of various ideas in storage.

What’s unfortunate is that he’ll retire before we’re able to see most of these ideas turned into films. As for me, I’ll be gratefully watching those that do, and this one especially took quite a few years to be completed. I probably shouldn’t say it like that, but Miyazaki… is an old man now, he’s the same generation as my parents. And I find it quite impressive that someone this age is willing to continue making movies until the very end, you don’t see that every day. He’ll probably be making animated movies until he dies, and if anything, I’m happy that I’ll get to enjoy his ideas and images for as long as his career goes on. With each generation, people’s mindset, nuance, and mood all change along. That’s how humans are, right ? And that’s why being able to witness these changes is so interesting : it’s like watching history itself unfold. I guess… people’s lives are interesting (laughs).

So you didn’t take part in the movie ?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: No, in the end I didn’t. I guess I’m the only one left who never got back to make at least one movie with Miyazaki after leaving Ghibli… Though to tell the truth I’ve been doing in-betweens here and there through my wife who works there. But as for key animation, Princess Mononoke really was my last collaboration with Miyazaki. I feel kinda sorry about it, but I do my best to spread what I’ve learned from him through the world, simply in a different form. Though Miyazaki himself would probably say something like “God that guy’s useless !” but well, works for me, that’s just how he is huh ? (laughs) For my part, I think I’ve successfully sown his seeds around.

Have you thought about following Iso onto his next project ?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: I don’t know what that is yet, but if the timing works out for me, I’ll definitely want to be a part of it, yes. But knowing Iso, as he moves on to his next work he’ll probably want to switch art styles as well, so if I’m in, there’s a chance it’ll be as a key animator this time. That being said, even if he does try on a new style, which I think is always a good thing, in the end it will still be an Iso project, his touch will remain whoever ends up being the designer. So I wonder how much I could get involved this time.

“It’s going to become increasingly important to master digital animation tools”

Finally, let’s talk a bit about studios. Are you in-house at +h now?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: No, I’m a freelancer.

And do you plan on working there again?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: I think there’s a good chance of that happening. I mean… I’m saying that, but I’ll also be working for other studios for sure. Anyway, that’s a possibility, yes.

Compared to Sunrise, Ghibli or Bones, how would you describe the atmosphere at +h ?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Well it’s still a very new studio, so we haven’t quite gotten to that “studio atmosphere” yet. I’d say whoever becomes the next center of attention will probably set the tone for the first time. It could be Iso, or the character designer for Dead Dead Demon’s Dededededestruction… At this point, I can’t tell who or what work will become the face of +h.

I’ve heard that you’ve been working on an iPad pro for a few years now, but before you drew on paper right ?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: I started using it halfway through The Orbital Children. I first drew everything on paper, then… well it’s not like I switched completely to the iPad, but I used it for designs and preparatory drawings. I stuck with paper for the animation and correction work, except for one cut I think.

So The Orbital Children wasn’t all digital ?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: For my part at least, pretty much everything was done on paper.

I see, that’s really surprising.

Ken’ichi Yoshida: (Showing a storyboard on his iPad) Back at the storyboard phase, I’d use the digital tools to edit the drawings, play with the layers like this, using the touchscreen and all. This way I have a better view of the action playing out in the storyboard, and I can clean up the characters as they appear in the panels of the storyboard. I started using this a lot around the middle of the production, from episode 3 and onward. Thing is, as an animation director, when I simply gave the storyboard to the key animators I had to do a lot of correction work afterwards, which took too much time and was starting to put a lot of pressure, so I set up this digital method of working from the storyboards first before giving the cuts to the animators. Thanks to that, the animators returned with good key frames simply needing a few adjustments.

So you haven’t gone fully digital?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Not completely, no. I can’t really do more anyway, because I’m not using Clip Studio’s animation tools, instead I’m using the illustration tools. So when it comes to digital drawing, I can still only do illustrations. I thought I’d learn on The Orbital Children, but eventually it was too much, too fast for me to assimilate.

You don’t use blender, then ?

Ken’ichi Yoshida: Well, Iso did tell me to try it, but truth is once the production had started, I couldn’t find any spare time to do so… I ended up doing everything on paper because it was the fastest way to go. It was just too hard to pick it up halfway through. Despite all that, I think from now on it’s going to become increasingly important to master these animation tools, and I can’t afford to sleep on it anymore.

That was all extremely interesting. Thank you very much for your time.

Interview by Ludovic Joyet and Matteo Watzky.

Introduction and notes by Matteo Watzky.

Translation by Lilo Chiche.

All our thanks go to Mr. Yoshida for his time and kindness, Mr. Fuminori Honda for welcoming us and for their cooperation.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

Footnotes

[1] Masashi Andô (1969-). Animator. Former member of Studio Ghibli, he became one of the closest collaborators of director Satoshi Kon following his departure. One of the foremost animation directors and character designers in Japan, he is scheduled to work on Sunao Katabuchi’s next film, The Mourning Children.

[2] Yoshiyuki Tomino (1941-). Director. One of the most important directors in anime history. Starting his career on Astro Boy, he is most famous as the creator of the Gundam series and one of the greatest SF creators in Japan. In recent years, he has been busy on the Gundam: Reconguista in G series, after which he is said to maybe retire.

[3] Tomonori Kogawa (1950 -). Animator, character designer. One of the close collaborators of director Yoshiyuki Tomino, he is particularly well-known for his character designs on Space Runaway Ideon, Combat Mecha Xabungle and Aura Battler Dunbine. His unique designs and attention to anatomy made him one of the pioneers of realistic animation in the early 1980s.

[4] Ichiro Itanô (1959-). Animator, director. One of the most important mecha animators in Japanese animation history, well-known for inventing the “Itano Circus” or “Missile Circus”, a technique in which a moving camera flies alongside missiles going in all directions.

[5] Yoshinori Kanada (1952-2009). Animator. One of the most important artists in Japanese animation history, who revolutionized mecha, effects, and character animation. Sometimes nicknamed “the father of sakuga”, he was one of the first animators to be widely recognized for his unique style. He has spawned generations of students, from Masahito Yamashita to Hiroyuki Imaishi and Yoshimichi Kameda. Notable works include Invincible Super Man Zambot 3, Galaxy Express 999, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind…

[6] Yoshikazu Yasuhiko (1947 – ). Animator, illustrator, mangaka, director, and character designer well-known for his collaboration with studio Sunrise as the character designer and animation director of Mobile Suit Gundam. There, he revolutionized character design philosophy. He was also an extremely talented animator who set a gold standard for realistic character acting in the 1970s. Today, he is still active as a manga artist and director.

[7] Rumiko Takahashi (1957-). Mangaka. Major mangaka throughout the 1980s and 1990s, who contributed to the mainstreamization of love comedy in shônen and seinen manga with works such as Urusei Yatsura and Maison Ikkoku. She is well-known for her beautiful female characters, and most of her work has been adapted into famous anime series.

[8] Shigeto Koyama (1975-). Mechanical designer. Famous for his collaborations with studios Gainax and Trigger and his slender, elegant machine designs. He also contributed to the Eureka Seven series.

[9] Katsuya Kondô (1963-). Animator, character designer. A pillar of studio Ghibli since nearly its creation, he has contributed to many of the studio’s movies as either animator, animation director or character designer. He is particularly famous for being character designer on Kiki’s Delivery Service.

[10] Future Boy Conan. 1978 TV series, dir. Hayao Miyazaki, Nippon Animation. Hayao Miyazaki’s first and last work as director on a full TV series, it is widely considered to be one of the greatest TV anime of the 1970s, if not of all time. The quality of its animation has left an impact on entire generations of artists.

[11] From the Apennines to the Andes. 1976 TV series, dir. Isao Takahata, Nippon Animation. Isao Takahata’s second of three World Masterpiece Theater series. Served by excellent animation and a harrowing story, it is famous for its sense of social realism and the quality of the layouts done by Hayao Miyazaki.

[12] Hikawa Ryûsuke (1958-). Critic, historian. Formerly active in anime magazines in the late 70s, he has become a fulltime writer since the 2000s. One of the greatest experts in anime and tokusatsu history in Japan, he has been teaching for several years at Meiji University.

[13] Toshiyuki Inoue (1961-). Animator. Nicknamed “the perfect animator” and widely considered to be one of the greatest animators in history, as well as one of the most knowledgeable persons on the history of Japanese animation. Famous for the realism of his animation and his adaptability, some of his representative works include Akira, Ghost in the Shell and Maquia: When the Promised Flower Blooms. He was chief animation director on Mitsuo Iso’s Dennô Coil and main animator on The Orbital Children.

[14] Akio Sugino (1944 – ). One of the most important character designers of all time, he was one of the founding members of studio Madhouse and is well-known for his collaborations with legendary director Osamu Dezaki. Their most famous works together include Ashita no Joe, Aim for the Ace, Nobody’s Boy Remi, Space Adventure Cobra, Dear Brother, Black Jack… Sugino is still active today as an animator.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Oshi no Ko & (Mis)Communication – Short Interview with Aka Akasaka and Mengo Yokoyari

The Oshi no Ko manga, which recently ended its publication, was created through the association of two successful authors, Aka Akasaka, mangaka of the hit love comedy Kaguya-sama: Love Is War, and Mengo Yokoyari, creator of Scum's Wish. During their visit at the...

Ideon is the Ego’s death – Yoshiyuki Tomino Interview [Niigata International Animation Film Festival 2024]

Yoshiyuki Tomino is, without any doubt, one of the most famous and important directors in anime history. Not just one of the creators of Gundam, he is an incredibly prolific creator whose work impacted both robot anime and science-fiction in general. It was during...

“Film festivals are about meetings and discoveries” – Interview with Tarô Maki, Niigata International Animation Film Festival General Producer

As the representative director of planning company Genco, Tarô Maki has been a major figure in the Japanese animation industry for decades. This is due in no part to his role as a producer on some of anime’s greatest successes, notably in the theaters, with films...

Trackbacks/Pingbacks