Japan Tours Festival is an event we love to attend each year. There, you can take part in very interesting conferences involving animation industry professionals, such as some regulars like mecha designer Stanislas Brunet, animation producer Séverine Varlette, and Jujutsu Kaisen powerhouse animator Benjamin Faure. They also manage to invite artists from Japan every year.

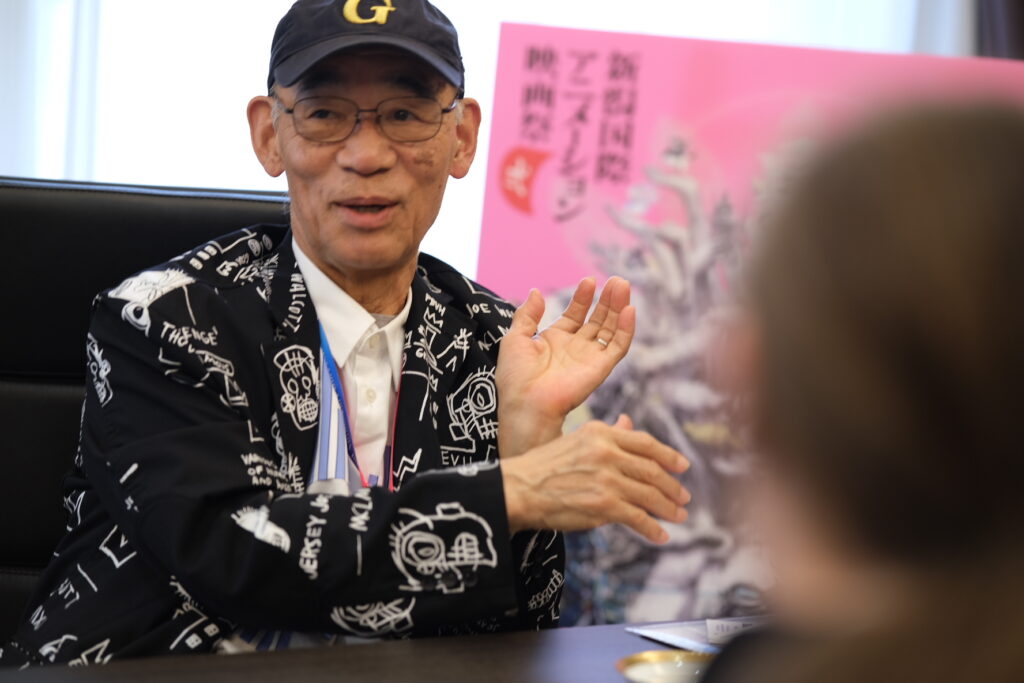

This summer, they invited a talented duo known for their exceptional collaboration, which we had the honor of interviewing – anime director Ryôsuke Nakamura and character designer Mieko Hosoi. Their remarkable partnership has resulted in the creation of several popular shows, including the humorous Aiura, the isekai Grimgar: Ashes and Illusions, and the adaptation of Taku Mayumura’s SF novel Psychic School Wars, a movie that boasts impressive compositing and hyperactive animation. Nowadays, they produce mostly openings and endings for shows such as March Comes in Like a Lion, Arakawa Under the Bridge, Made in Abyss, Attack on Titan, Your Lie in April…

While they regularly appear at Comiket, this was the first time they attended a European event.

Ryôsuke Nakamura’s career began at Studio Madhouse after being scouted by studio president Masao Maruyama. During his time there, he developed a close friendship with Tetsurô Araki, who went on to direct worldwide successes such as Death Note, the first three seasons of Attack on Titan, and Kabaneri of the Iron Fortress.

Meanwhile, Mieko Hosoi has established a reputation for her elegant character designs, such as those of Showa Genroku Rakugo Shinju, and expressive animation in works such as Psychic School Wars.

Discover more about their impressive work together in our exclusive interview.

This article is available in Japanese. 日本語版はこちらです

This article would not have been possible without the help of our patrons! If you like what you read, please support us on Ko-Fi!

“That was the first time we worked together, but it was really powerful”

I’m going to start with a delicate question, but are you two a couple?

Mieko Hosoi: Not at all! (laughs)

Ryôsuke Nakamura: That would be annoying. (laughs)

I was thinking about it because you often work together. So, to begin with, could you tell us a little about how you met?

Mieko Hosoi: We began working together on the animated adaptation of Kaiji.

Ryôsuke Nakamura: It was in 2007, right?

Mieko Hosoi: Yes, that’s right. I really liked Kaiji’s original manga, and this was the first time Madhouse, the studio I worked for, entrusted me with an important episode as an animation director. I knew I had to work very hard, so I went to the studio and discovered that Nakamura was in charge of the storyboard and direction. I was given a very good storyboard, and I guess that was our first encounter.

Ryôsuke Nakamura: Yes, there’s an episode in Kaiji where the main characters cross a steel bridge, which is a thrilling part of the series. I directed the 13th episode, and Tetsuro Araki, a good friend of mine, directed the following one. I wasn’t just going to handle the storyboards; I was also slated to direct the episode. So I was a bit worried about the animation director. Actually, I had heard that someone different was going to be the animation director, but there was a last-minute change, and it became Hosoi. I believe that her previous work had been really appreciated and that the director and producer agreed to give her the job.

And so you two ended up being a perfect fit for each other!

Ryôsuke Nakamura: That was the first time we worked together, but it was really powerful.

Could you please explain how you two work together?

Mieko Hosoi: Usually, Nakamura handles the storyboarding and direction, and I do the animation.

Ryôsuke Nakamura: It depends on the format, but you also do the character designs, and if it’s a film or a TV series, I often write the screenplay as well.

Ms. Hosoi, what do you think is the appeal of Mr. Nakamura’s direction?

Mieko Hosoi: Well, let’s take the example of Kaiji. It’s got a very distinct style. That’s what makes it so good, but it makes it particularly difficult to adapt. To do that, you need a certain level of commitment. And so, depending on their tastes, people might end up dissatisfied with the adaptation. To put it clearly, it might often deviate from the original… In Nakamura’s case, he really cared about the original work, so even though he would never reproduce the manga’s panels and make something completely different, the final emotional impact is exactly the same. This really impressed me. It’s as if he managed to capture the spirit of the original work better than the original work itself.

Mr. Nakamura, for you, what’s appealing in Ms. Hosoi’s designs and work as an animation director?

Ryôsuke Nakamura: Above all, it’s how powerful it is. Sorry, but I’ll get a bit technical here.

I begin work by meeting with the key animators, receiving their completed layouts and then reviewing them. It’s at that point that my work coincides with Hosoi’s: as animation director, she reviews the drawings I already checked, corrects them, and sends them back to the animator. Then, the key animator draws their key animation and sends it to me for review. That’s when I see the result of Hosoi’s work and can see her drawings.

In reality, there can be a considerable time gap between these steps. The first time the first keyframes arrived, I saw how much Hosoi’s corrections had done and was shocked by how powerful they were. She had made so many changes that I realized I didn’t need to do as much on my end, and that made things easier for me as well.

Also, on TV series, there are limits on the budget and number of frames you can use, so I often have to give up on having to move some things, for example, tears welling up or the clouds fluttering up in the wind… I always think these should be given life, and Hosoi makes that real: everything starts to move, and thanks to her, the animation gives off a remarkable level of motion and life.

Mieko Hosoi: From my position as an animator, my job is to receive storyboards and turn them into pictures. But depending on the storyboard, I’m not always convinced – such as how the characters express their emotions or things like that. But that never happens with Nakamura’s storyboards: the way he expresses things never feels wrong, and I have that confidence in me when I transform the storyboard into my drawings. That’s how Nakamura’s storyboards are for me.

You’ve been working together for quite a long time. Working with friends probably isn’t always easy, right?

Mieko Hosoi: We fight a lot. (laughs)

Ryôsuke Nakamura: People who aren’t close don’t really fight because they never truly exchange their opinions. However, when you’re close to someone, it’s easier to assert what you think, which is when fights happen.

Mieko Hosoi: It’s something I often feel about the animation industry: a lack of communication. People don’t talk to each other. There’s always something very awkward. On the other hand, Nakamura isn’t afraid to say things, what he likes or doesn’t like, even things that are difficult to say or hear. I’m very thankful for our relationship because of that.

Fighting is sometimes necessary to make something good.

Mieko Hosoi: That’s right.

Ryôsuke Nakamura: I have an even longer relationship with art director Hidetoshi Kaneko than with Hosoi. He passed away three years ago, but he was about the same age as my father, so we couldn’t really get into arguments. He had much more experience, could anticipate my shortcomings, and support me accordingly. In Hosoi’s case, we’re closer in age, so neither of us is above or below the other. We engage in healthy debates, challenging each other’s perspectives, all in order to make something better each time.

“Mr. Dezaki was very good at anything that involved having fun”

I know this is a simple question, but when did you start drawing?

Mieko Hosoi: Really, as long as I can remember… I’d just copy the manga that was there, and I pretty much spent all my time with a pencil in hand. I was probably already drawing back when I was 3 or 4…

Ryôsuke Nakamura: I began drawing when I began working in animation. As a child, I didn’t really watch animation… I decided to do that job because of my time in college: I was in the children’s literature club, and my friends there were animation fans, so I was influenced by them. So, I didn’t enter this industry to realize a lifelong dream or anything: I initially intended to spend 2 or 3 years in animation and spend that time thinking about what I really wanted to do: writing. So I was thinking about looking for something else completely different all the time, but I found animation direction to be so interesting that I decided to stay. Going back to your question, since it’s only at that point that I started drawing, I was absolutely awful at it at first.

And how about now?

Mieko Hosoi: It’s hard to describe, but his “style” isn’t really rooted in anatomy, perspective, or volume, but it’s about conveying things. In that regard, he’s very good and is able to do things that I can’t even come close to.

Mr. Nakamura, your family must have been very strict. They mustn’t have been happy when you joined the industry…

Ryôsuke Nakamura: Yes, that’s right.

You graduated from Tokyo University, right?

Ryôsuke Nakamura: (Laughs) You know your stuff, don’t you? As far as I know, Isao Takahata is probably the only other one I know about.

That’s right. How did your family react when you entered the industry? Weren’t they angry? Are they fine with it now?

Ryôsuke Nakamura: Everything’s alright now (laughs). My father was an FM radio director, so I think he was more understanding of my career choice.

I see. It’s show business.

Ryôsuke Nakamura: Yes, we are the same in that sense.

Ms. Hosoi, you graduated from an art college, right? How did you get into the animation industry?

Mieko Hosoi: I am ashamed to admit this, but it’s because of my love for Osamu Tezuka’s manga. I was studying design, but I wasn’t sure what career path to follow. It was then that I saw that Tezuka Production was recruiting, and I applied because it was Osamu Tezuka’s company. (laughs) I liked anime, but I didn’t have any technical knowledge or anything. So, of course, I couldn’t do animation… The only thing I said at the interview was that I loved Osamu Tezuka… Everybody laughed at that, and I thought I had failed, but somehow I got in. (laughs)

Ah, I wanted to talk about Tezuka Pro as well, but before that… All the animators I’ve talked to who went to technical schools said it hasn’t been useful at all. But how about art college? It must have been useful, right?

Mieko Hosoi: Well, it’s just my own feelings based on my experience, but I think learning by practicing is the best way to learn. That was the case for me. I was taught by my seniors at Tezuka Pro, and even though I may have been a big nuisance for them back then, it was really for the best! (laughs)

Osamu Dezaki used to work at Tezuka Productions, didn’t he? What was he like?

Mieko Hosoi: Well, I often got the feeling that Director Dezaki was more interested in having fun with me than strictly working together (laughs). To this day, I genuinely believe that I’ve never encountered such a remarkable person as him. It’s difficult to put into words, but he had this remarkable ability to be both childlike and incredibly mature at the same time. Moreover, despite the fact that he was roughly the same age as my father, I never really felt the age gap between us. Of course, he was already an accomplished director when I first met him, but he never came across as stiff or formal; he was always natural and easygoing. This is precisely why I never sensed any barriers between us; we hung out as if we were close friends.

Ryôsuke Nakamura: I’m jealous!

Can you tell us about a funny memory from your time at Tezuka Production?

Mieko Hosoi: A lot!

One is from the time of Hakugei: Legend of the Moby Dick. It wasn’t supposed to be done at Tezuka Pro at first, but the schedule became too tight, and it was interrupted a first time. That’s when Tezuka Pro came in and took it over. It seems that it was all driven by Mr. Dezaki’s passion for it. He’d usually draw all the storyboards himself, but his way of doing things was usually to do that at home. But Hakugei was the only time he had a desk prepared for him at Tezuka Pro, where he’d write storyboards. He’d arrive at the studio just before the last train – so, in the middle of the night. When he arrived, he’d invite everybody out for meals, including even young animators like me, and after that, we’d go to the karaoke. We would stay out until 3 or 4 in the morning, far too late to come back home. But in the morning, Mr. Dezaki began working. The rest of us locked ourselves in the studio, caught a bit of sleep, and then began working as well.

Was Osamu Dezaki good at karaoke?

Mieko Hosoi: Yes, he was very good. In general, he was very good at anything that involved having fun. He was passionate about music in general. He was very close to Mr. Yuji Ohno, the composer of the music of the Lupin series, and so sometimes he’d invite us to this small livehouse he owned in Shinjuku.

This is a silly question, but what kind of songs did Director Dezaki sing?

Mieko Hosoi: Songs about booze and tears, men and women, things like that.

Ryôsuke Nakamura: So enka?

Mieko Hosoi: Yes, kind of.

Blues?

Mieko Hosoi: He often did blues songs! It was very typical of him to sing songs like that, in which you could feel the weight of life.

So, really, things with Ashita no Joe vibes, right?

Mieko Hosoi: You know, he did sing some Ashita no Joe sometimes! I guess he liked that too. (laughs)

Could you please tell us about your teacher, Mr. Shinji Seya, as well?

Mieko Hosoi: Mr. Seya was my instructor. He maintained strict standards in many aspects and embodied the very principles he imparted, even admonishing me not to stand up too frequently from my seat while working. How could I say… To illustrate the extent of his rigor, there was a substantial chain binding the desks’ legs to the chairs to secure them (laughs). He would twirl it around so the chairs would be stuck to the desks to restrain us. That’s how strict he was. But when we talked, he was not harsh at all. I mean, he never yelled at me or anything like that, but there was a sense of severity in every word he taught me (laughs). Still, I’ve never received any direct critiques or admonitions for going to karaoke sessions with Director Dezaki.

“It would be hard to pinpoint any job that isn’t important”

Mr. Nakamura, you graduated from Tokyo University and started as a scriptwriter but also did some animation. Isn’t that unusual?

Ryôsuke Nakamura: I did some animation, but an animator’s most specific task is the final cleanup, and that’s something I can’t do, so I really didn’t do much. It’s just that whenever we lacked people, I would fill in the gap.

So, in the end, you had a hand in all the aspects of the industry: director, episode director, key animator, scriptwriter… What would you say is the most difficult job in animation?

Ryôsuke Nakamura: The hardest job? That’s a very difficult question. Every role comes with its own set of difficulties. However, if I were to pick one, I’d say that being a director is the most demanding job in this field. The first reason is how much pressure there is. The second is that there’s nobody in your staff who truly understands the work you’re doing. The director is always alone. Nobody ever praises the director. Japanese people don’t really say these kinds of things, even if that’s what they think. So the only thing the director hears are the complaints… In that sense, it’s very important to be surrounded by people who can alleviate some of that loneliness and be there when you’re starting to feel pushed into a corner.

And on the other hand, what’s the most interesting job?

Ryôsuke Nakamura: Everything’s interesting to some degree, of course, but I think that being episode director would be the most interesting job for me.

And the most important one?

Ryôsuke Nakamura: The most important job… It’s really impossible to choose. In fact, it’d be hard to pinpoint any job that isn’t important. Budgets aren’t high in the first place, so we already have to make compromises. Frankly, if any aspect of the production was compromised, it would have a cascading effect on the whole.

Mieko Hosoi: Overall, for the sake of the work, people would usually say that the most important thing is the scenario, wouldn’t they?

Ryôsuke Nakamura: For the work, huh… Certainly, if the scenario isn’t good, the people who have to work with it will find it boring even though they have to do it anyway. Whereas if it’s good, it will make the staff more motivated. So I agree that it’s something very important.

I would like to talk a little about Psychic School Wars. I heard the production period was on the short side. It’s hard to believe, looking at the final product. Was the budget really high?

Ryôsuke Nakamura: I don’t know if I should tell you how much, but the budget was quite small for a regular movie.

It is a very unique work, particularly the color design and the photography. Could you please tell us more about it?

Ryôsuke Nakamura: The script for Psychic School Wars posed some considerable challenges. The initial scriptwriter gave up on the initial script, and it led to discussions on whether or not we should even go on with the project. Ultimately, we agreed that if I rewrote it, it could continue. It took multiple writing sessions for me to do that, but my skills weren’t up to the task, and the script didn’t end up interesting enough. However, on this film, I tried out for the first time things that I had wanted to do for some time regarding animation, photography, and so on… In that sense, I think it’s my most ambitious and challenging work.

As an analogy, if you think about auto racing, when preparing for a race, you have to plan meticulously to ensure the car performs at its maximum speed without crashing. That’s the good way to go, but that is not really what happened on Psychic School Wars: it was more wild and youthful, keeping the foot on the accelerator all the way, even if it meant getting into obstacles.

Since very early on, I’ve often been told that my work felt like it came from someone with experience, despite my young age. On Psychic School Wars, I wanted to try out that kind of inexperienced method. In the end, it aligns well with the theme of the work since it’s a teen movie.

It’s a great film. The lens flare effects, in particular…

Ryôsuke Nakamura: That’s right. This kind of technique has become more prevalent nowadays, but back then… I was already aware of Makoto Shinkai’s work, but that was still before he transitioned to making more commercial works, and in commercial anime, lens flares and such weren’t used a lot, so I wanted to try it out.

I don’t know how it is overseas, but in Japan, “youth” carries profound significance, and depicting it as a theme is crucial. So, I attempted to use lens flares as a means to convey youth in my own unique way.

Talking about light flares in animation, what about Yoshinori Kanada’s flares?

Ryôsuke Nakamura: I believe Kanada’s effects are more design-oriented. In my case, I prefer the kind of effects that naturally come from the use of lenses rather than the intentionally designed effects often associated with Kanada.

The other thing is that Psychic School Wars moves all the time. Wasn’t that difficult?

Mieko Hosoi: It was not easy. However, we were fortunate to have an exceptionally talented animation team.

All the animation directors were extremely skilled, and all drew key animation on top of that… On my end, it was a huge workload to supervise all the drawings, but it was a truly fulfilling environment.

Unfortunately, the time allotted for this interview did not allow us to introduce all the elements we wanted to cover. Thrilled by our talk, Mieko Hosoi and Ryôsuke Nakamura seemed eager to continue our discussion on a future occasion. Mr. Nakamura, in particular, was keen to discuss animation techniques in depth. Stay tuned for an upcoming sequel to this article!

We wish to thank Mr. Nakamura and Ms. Hosoi for their time and kindness, as well Sarah Marcadé from Japan Tours Festival for helping us set up this interview and Peter Rong from Manganimation.net thanks to whom this interview was made possible.

Interview by Ludovic Joyet and Antoine Jobard.

Translation by Antoine Jobard and Matteo Watzky.

This article would not have been possible without the help of our patrons! If you like what you read, please support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Oshi no Ko & (Mis)Communication – Short Interview with Aka Akasaka and Mengo Yokoyari

The Oshi no Ko manga, which recently ended its publication, was created through the association of two successful authors, Aka Akasaka, mangaka of the hit love comedy Kaguya-sama: Love Is War, and Mengo Yokoyari, creator of Scum's Wish. During their visit at the...

Ideon is the Ego’s death – Yoshiyuki Tomino Interview [Niigata International Animation Film Festival 2024]

Yoshiyuki Tomino is, without any doubt, one of the most famous and important directors in anime history. Not just one of the creators of Gundam, he is an incredibly prolific creator whose work impacted both robot anime and science-fiction in general. It was during...

“Film festivals are about meetings and discoveries” – Interview with Tarô Maki, Niigata International Animation Film Festival General Producer

As the representative director of planning company Genco, Tarô Maki has been a major figure in the Japanese animation industry for decades. This is due in no part to his role as a producer on some of anime’s greatest successes, notably in the theaters, with films...

Recent Comments