Ryôichi Ikegami is a manga veteran. As of 2023, the author of Crying Freeman and Sanctuary is currently 78 years old, and after a 60-year career of drawing manga, he is still in surprisingly great shape. He is now drawing the energetic and youthful manga Trillion Game with Rîchiro Inagaki as a writer, who wrote the popular mangas Dr. Stone and Eyeshield 21. Ryôichi Ikegami is a fascinating artist because he has lived through every single era of modern manga, from the times of loan manga and experimental avant-garde magazines, by passing through the weekly magazines of the economic bubble to the status quo of nowadays. With his realistic and detailed sublime drawings and his fluid and dramatic storyboarding, he is one of the most recognizable figures of the gekiga movement. This artistic wave showed a more adult face of manga as an art form. Ryôichi Ikegami is mainly known for his intense and manly yakuza series. But one of the most fascinating aspects of his art is the addition of eroticism and sexual tension to that whole genre. In January, we had the immense chance to listen to Ryôichi Ikegami talk about his career at length during two panels, one reserved for the press and a public one.

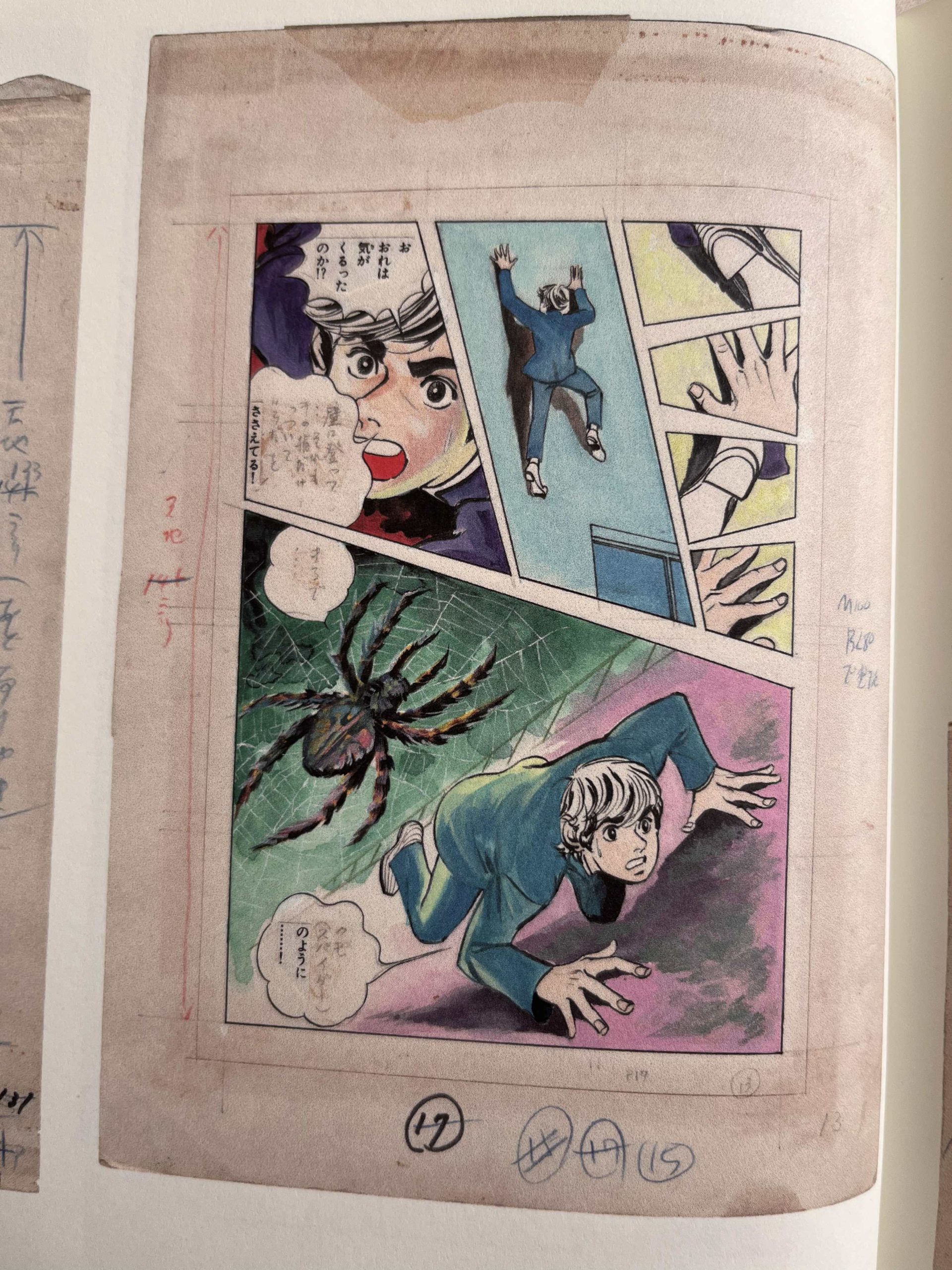

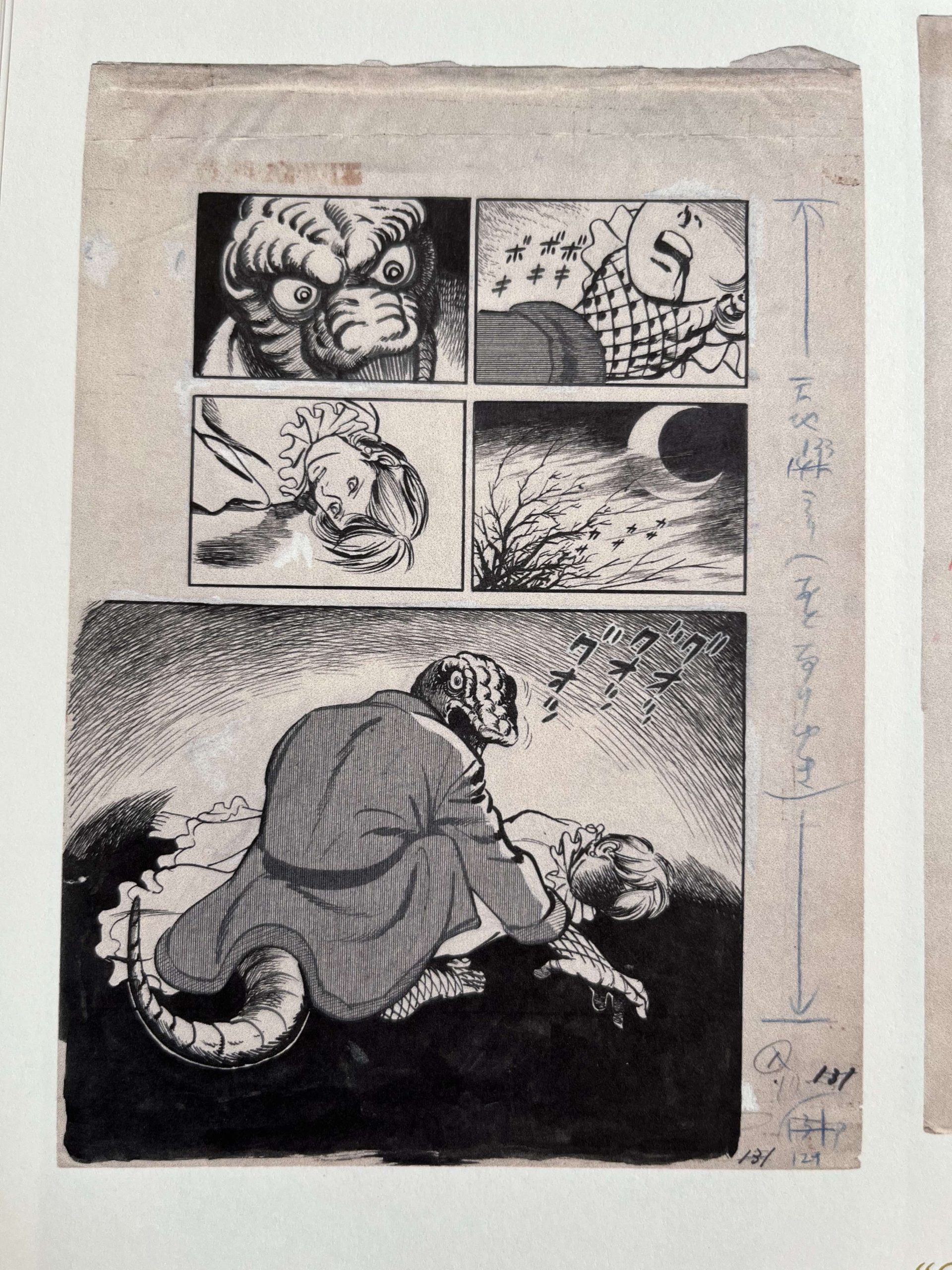

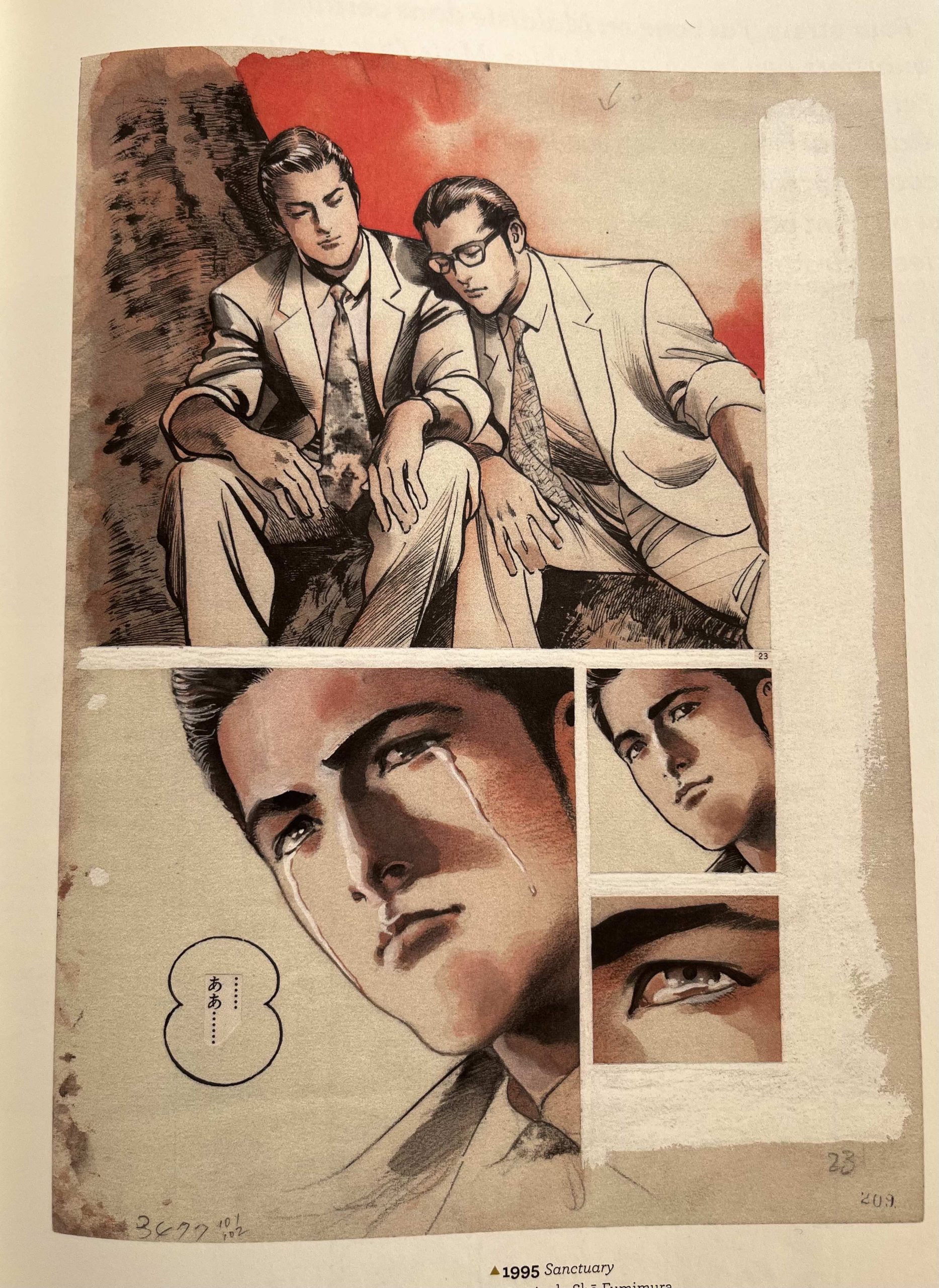

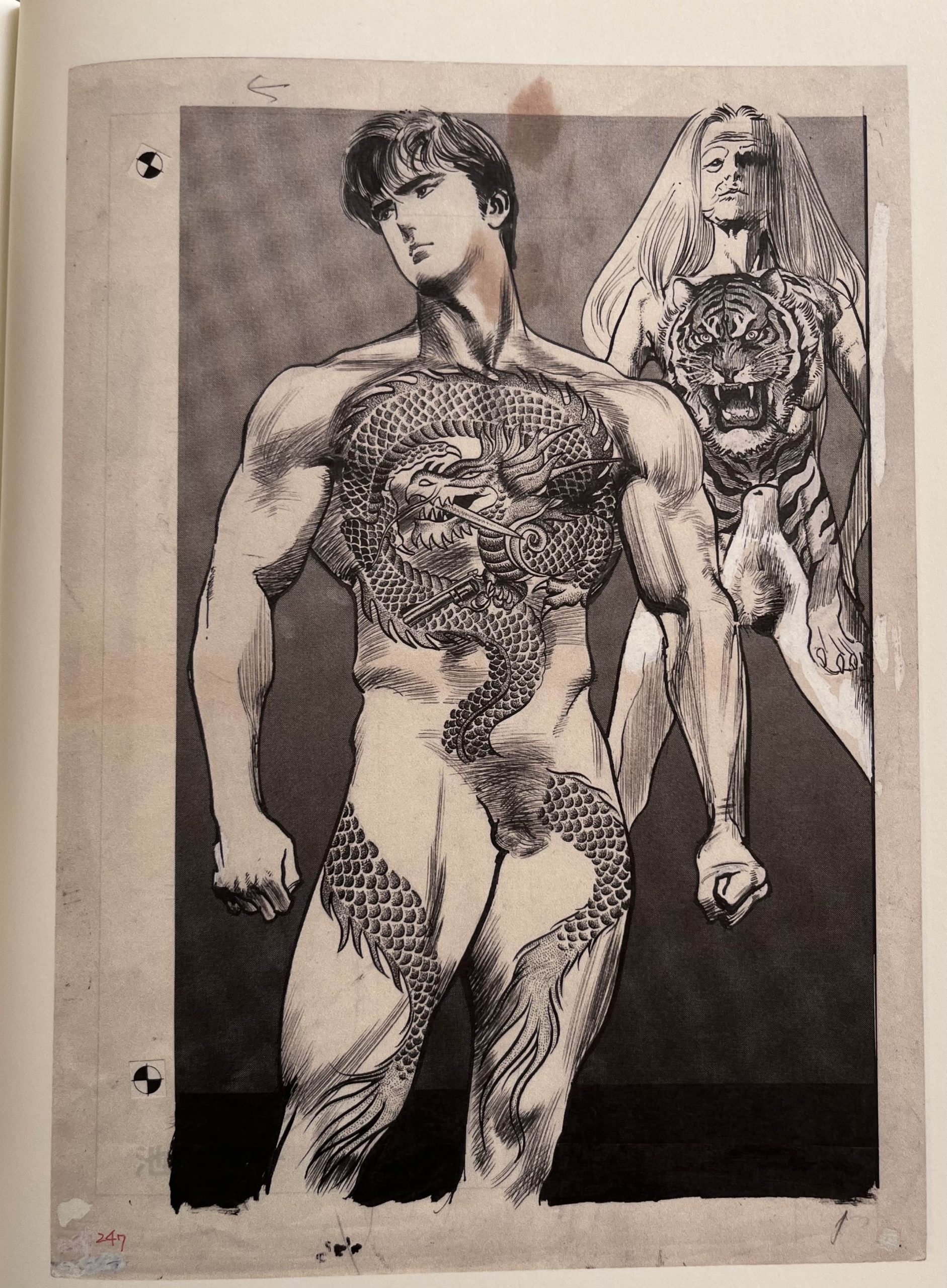

The 2023 edition of the Angoulême International Comics Festival was rather special because it felt like manga was the central focus of the festival. Three major manga artists of different generations were invited: Hajime Isayama, Junji Itô, and, of course, Ryôichi Ikegami. A vast exhibition covering Ikegami’s career with plenty of original manga pages and paintings was available at the Museum of Angoulême. We could see with our own eyes the incredible skills of this manga veteran.

Those two long talking sessions with Ryôichi Ikegami were a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to hear this much from a manga artist with such a long career; if you’re interested in manga history, this is a must-read. We’re delighted to share it with you, and we would like to thank every person who helped organize Ryôichi Ikegami’s visit to the Angoulême festival.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

Ryôichi Ikegami’s press conference

Questions were asked by journalists present and pre-selected by Glénat Editions, French editor of Ryôichi Ikegami’s Sanctuary, Trillion Game, and Crying Freeman. Questions in italic were submitted by our team at fullfrontal.moe

The press conference was hosted by Benjamin Daniel, better known under the name of his YouTube channel, Benzaie, on which he mainly discusses video games.

Ryôichi Ikegami: Thank you all from the bottom of my heart for you being here to see my drawings.

Benjamin Daniel: Thanks a lot for being here, Mr. Ikegami, especially at Angoulême, my hometown. My name is Benjamin Daniel, aka Benzaie. Glénat Editions invited me to host this interview between journalists and this great master of drawing. It’s a great honor that makes me feverish. I hope you will all share this great pleasure with me. We have plenty of luck to have such an opportunity here in Angoulême. Again, thanks a lot, Mr. Ikegami.

Ryôichi Ikegami: It has been a very long time now that I draw beautiful men and beautiful women. I’m used to drawing beautiful people, but my wife says I look like an artifact of the Jomon period* [laughs]. I only draw idealized characters, but the real me is just this guy in front of you. Therefore I ask for your understanding.

Benjamin Daniel: Thanks a lot for this introduction [laughs].

Ryôichi Ikegami: I don’t know if you have seen my exhibition, but I started working on manga at 17 years old, and this year I will be 79. It’s a selection of drawings of my entire career, and to be honest, there are some that I had completely forgotten, and I came to the realization that I have really drawn a lot throughout my career. In that exhibition, I truly felt how eras changed and followed one another and how my art changed according to them. Depending on the point of view, some can say that these are evolutions, but to me, they are rather changes. Manga themes change according to their times, and techniques also change, for example, when digital drawing came, etc. But techniques are just tools. To be honest, I don’t consider them as evolutions but simply as changes. I want you to keep that in mind when you see my exhibition. By the way, I’ve seen that you asked me many questions and I prepared some answers for you.

Benjamin Daniel: You already almost answered the first question on the evolution of your art and your working method. I wanted to start by asking about what you think about Angoulême. Do you like the town? Just to quickly go over it before getting into the heart of the matter on his work.

Ryôichi Ikegami: I feel like I’m in Wonderland! In the Middle Ages! I’ve already seen a bit of Angoulême on TV before. When I got off the train, I started walking around town, and it was like the Middle Ages. If we removed modern elements while only keeping the buildings, it would be like that. It’s incredible. In Japan, you see this kind of scenery in some remote areas in Kyoto or Nara, but here it’s the whole city that is like that.

Benjamin Daniel: Being from Angoulême, I’m very pleased to hear that. Thanks a lot, Mr. Ikegami. Since you already talked about how you feel about the evolution of your working techniques, let’s start with another question. How did Yoshiharu Tsuge’s* work, a legendary mangaka from the 60s and 70s, influence you?

Ryôichi Ikegami: I love the first works of Yoshiharu Tsuge’s career, his kashihon* manga. I liked his works, but they worried and distressed me while reading them. They are everyday life stories with little modifications where we really feel the cruelty of this time. I grew up reading shonen manga, stories with ideal heroes that were like a catharsis for the readers. But Tsuge’s mangas were about people of everyday life, showing the sadness and joy of their simple lives. In Garo*, he started talking about his travels and other things, but this sort of combination of joy and cruelty in his first works is what really impacted me. I want to talk respectfully about him, so I will call him sensei.

When I worked at Mizuki Productions with Shigeru Mizuki-sensei* and Tsuge-sensei, we had a lot of sleepless nights. And during those times, strangely, Tsuge-sensei would simply disappear without warning. Sometimes for an entire week without warning Mizuki-sensei, who was his boss. Shigeru Mizuki was extremely busy working on Gegege no Kitaro, and he was starting to stress out because he was one person away from finishing his drawings on time. Tsuge-sensei was living in a building one floor above a ramen shop near Mizuki Productions, and everyone would check to see if he was there. We borrowed the keys to open it to see if he was there or not. It was an almost empty room with only a space where you could read lying on the floor. His room left me with a sensation of extreme loneliness. Tsuge-sensei was a person that tried to commit suicide after a heartbreak, and Mizuki-sensei, who was a very kind and positive person, was worried about him. But anyway, he always returned without warning or saying why he left for a week or what he did. Mizuki-sensei was worried to death, but when Tsuge came back, the only thing he did was laugh. They got along very well. So these are my memories about Mizuki Productions, and after that, he started drawing manga about his travels.

Benjamin Daniel: Thank you for those anecdotes about manga legends and the atmosphere of that time. Since we’re talking about Shigeru Mizuki, I would like to know the teachings you learned from him that left an impact on you since he trained you.

Ryôichi Ikegami: The greatest lesson I’ve learned from Shigeru Mizuki when I worked at Mizuki Pro is what he told me one day: “Life is nothing but a fart.” It might seem funny at first glance, but when you think about the whole universe, the cosmos, time, and space, even if we could live 1000 years, life is like a fart. And personally, I interpreted it as we might be nothing. It’s all the more reason to do things right.

Benjamin Daniel: I wasn’t expecting this as an answer, but this is a beautiful life lesson. About your work, at the exhibition, we have the opportunity to see original drawings of Spider-Man, Crying Freeman, Sanctuary, and so many legendary works of art. Among all these works, which one had the greatest impact on you and why?

Ryôichi Ikegami: Since Trillion Game is still ongoing, I won’t comment on it. I have drawn a lot of manga, but the one I remember the most is Otokogumi which I have worked with Tetsu Kariya*. This manga greatly impacted me because I was 26 or 27 years old, and there was an extreme passion for manga as a medium at that time. Every week we had to do sleepless nights. At the same time, I was doing I, Ueo Boy with Kazuo Koike*, Otokogumi was published in a weekly magazine, and the other was bi-weekly. Koike-sensei was very popular then, so he often submitted his scripts late. Therefore, regularly, my assistants and I had to do sleepless nights for about two weeks. At 6 a.m., we used to drink a drug called “Moka,” seemingly a bit like aspirin, and tasted like coffee, giving us energy. Unfortunately, that was just for an hour, and after that, we started to feel sleepy again. I have a lot of memories of that time when we were young, and we could work like this. If you want a funny story, at the time, there was a very popular shonen manga called Star of the Giants, and its author Noboru Kawasaki* was working for two magazines at the same time, Shonen Sunday and Shonen Magazine, so he was forced to not sleep at all. Obviously, he was starting to fall asleep on his drawings, and his editor next to him was stinging his neck with a very sharp pencil [laughs]. This is roughly what the world of manga in the 70s was like. Everyone was very young in the manga scene at the time, so there was a passion and a vigor that you can’t find nowadays, and when I read Otokogumi, I still feel that passion, that energy, that vigor.

Benjamin Daniel: Thanks for all those precious memories. We’re going to talk about Sanctuary, which came up later in your career. This is a very political work that is more relevant than ever nowadays. An event such as ex-prime minister Shinzo Abe who was assassinated with a homemade weapon, could be a story in Sanctuary that is almost 30 years old. About this political aspect, is it more complicated to draw a story that depicts a certain vision of contemporary society?

Ryôichi Ikegami: Many scandals at the time of Sanctuary agitated the political scene, but those scandals are often little known to the general public. That’s not specific to Japan. It’s common in a lot of countries. I think you need a certain amount of courage to speak about the backstages of the political world. I think that we were able to draw this manga because Japan is a democracy. In a more authoritarian political system, a more dictatorial one, it would have been harder to draw something like Sanctuary.

Benjamin Daniel: Thanks for that answer. In Sanctuary, the political class takes a lot of hits by your pen. Besides the two handsome main characters, there is an incredible gallery of caricatural portraits of Japanese politicians. We can feel some kind of disgust for this class. But it’s also a story about yakuza, depicted with both precision and romanticism. I would like to know how you documented yourself about the underground world of yakuza and organized crime since the Hong-Kong mafia is also present in Sanctuary. Did you personally approach that environment and meet people coming from it?

Ryôichi Ikegami: I think it would be better to ask this question to the scenarist of Sanctuary, Sho Fumimura* since he wrote the story. He never told me he was meeting yakuza for documentation, but I know he was getting information from people very close to the yakuza. However, in Heat, another manga about yakuza, there is a character who is the second in command of a yakuza organization. At one point in the story, he gets his face crushed on the ground. And after that chapter got published, I got a phone call to my office from someone with a distinct way of speaking; he would roll his Rs, which is often a bad sign. The reason for that call was that that character’s face looked like a real-life yakuza boss. I got afraid, and I changed my phone number. So yeah, real yakuza are really scary. It’s better not to mess with them [laughs].

Benjamin Daniel: It’s good that you mentioned that because I had a question from a stylistic point of view, you draw gangsters in a very emblematic way. Do you think that your way of drawing yakuza influenced yakuza themselves later on?

Ryôichi Ikegami: As I said, I think that some of them were reading my manga. And that’s why in a chapter, Sho Fumimura made a character say literally, “I don’t hate yakuza.” There was some kind of communication like this between us and them through the manga.

Benjamin Daniel: Now we’re going to talk about Trillion Game, the manga you are currently working on, that has a comedic aspect seldom seen in your career. Sometimes it’s hard to believe it’s a manga made by you. How did you approach that comedic, lighter tone, which is often very funny?

Ryôichi Ikegami: It’s thanks to my talented editor that I was able to embark on this work. That’s also because I have a genius scenarist Rîchiro Inagaki*. My editor was convinced that there could be an extremely interesting chemical reaction between my realistic drawing style and Inagaki’s scenario. Initially, I refused because I wasn’t sure I could do a good job on that type of work, and I advised them to find someone younger. But everyone looked disappointed and sad, so they insisted, and ultimately I accepted. The result is there. It’s a great entertainment manga, and I draw it as if it was my last. And yes, it will probably be my last manga.

Benjamin Daniel: Speaking about this new collaboration and new themes you have to explore in Trillion Game, I would like to know how you prepare yourself to start a new series, not just for Trillion Game, but even in the past; how do you approach working with a new scenarist?

Ryôichi Ikegami: When I work with a scenarist, first, I read the scenario, and the most important thing is if I like it or not; if it suits my tastes. It has nothing to do with political opinions; it’s strictly about quality. There has to be something in the scenario that makes me want to draw and that I feel there is something new about it. Also, it’s a bit weird to say, but it’s necessary that I feel like it could have some kind of commercial success. That’s how I choose my scenarios.

Benjamin Daniel: You’re also very known for your storyboarding and paneling. Your manga is known to have great reading fluidity. Could you give us some insights about your creative process on this paneling and storyboarding aspect?

Ryôichi Ikegami: First, I read the scenario one or two times. I read it very carefully, and I try to imagine the universe of the manga and also try to understand the state of mind of the scenarist. What kind of message does he intend to send? I make my own interpretation of it. After that, it’s up to me to stage it. What I try to do the most is that we don’t feel the space between the panels or even that the panels even exist to have the smoothest paneling possible with great reading fluidity. Obviously, it also depends on the content of the manga. Drawings change a lot based on the context. Manga is not about mastering drawing or making a good or bad illustration; it’s about having a drawing that fits the story’s theme. That’s what I pay attention to for staging in general.

Benjamin Daniel: That’s very impressive to have such a simple and clear method and to obtain a result that many could dream of. About drawings, your color spreads are also very famous. I particularly think about some Crying Freeman covers that are completely mythical. I would like to know what are your favorite methods of coloring and why?

Ryôichi Ikegami: When I was young, there were no computers, so we couldn’t do digital painting. We had to paint by hand. Nowadays, I just draw the basis and the line, and my assistants colorize it thanks to computer tools. And then, I add details with acrylic paint on the impression. That’s simply because I really like painting, so I want to keep doing it by hand. And I also want us to feel the physical brushstroke that can’t be obtained with computers. I don’t know how others do it, but it’s really important for me that we keep track of the use of the brush by hand. Whether for themes or coloring, manga is a medium where we are free as artists, so there is no real limit to what we can or can’t do.

Benjamin Daniel: I see, so that’s why we have a color spread of Trillion Game at the exhibition that is colorized digitally, but there is still an original drawing because you added acrylic paint to it. We’re now going to discuss the settings described in your manga. Politics, organized crime, and even the world of money and business in Trillion Game, which is set in the world of start-ups. All these settings are related to power structures. What attracts you to those kinds of settings?

Ryôichi Ikegami: Those are worlds where people deceive each other, where all it takes is one mistake to lose your life. I’m attracted to men living in those worlds, not just because it’s interesting, but because it has a very erotic kind of attraction. That’s why all the yakuza I draw are handsome! [laughs]

Benjamin Daniel: I have another question for you. What do you think about the international reach of manga nowadays and the fact that many Western authors are now making manga themselves?

Ryôichi Ikegami: Personally, I find that quite mysterious, but for example, a mangaka as famous as Katsuhiro Otomo was very influenced by Moebius*‘s Bande Dessinées. And a lot of mangakas are also very influenced by American comics. I think that it’s a wonderful thing that all those influences keep being exchanged between countries all over the world. Thanks to that, completely new visual styles are born.

Benjamin Daniel: It’s an honor that you bring up, Moebius. He is our national treasure, especially here at Angoulême.

Ryôichi Ikegami: I love Moebius!

Benjamin Daniel: It’s the 50th anniversary of the festival this year, and it wouldn’t be the same without Moebius’ legacy. Even Vinland Saga author Makoto Yukimura made a great tribute to him with a poster for the festival. Thanks a lot for mentioning our French authors. I have another question. You said you started working as a mangaka at 17 years old. I would like to know what manga made you choose this career.

Ryôichi Ikegami: I started reading manga and liking them in elementary school. My father was sick, so I was raised by my mother, and it was my big sister who brought me manga magazines. In those magazines, there was a little notice in the readers’ mail saying that if you became a mangaka, you would be able to build a house with a bathroom. It was just after the end of the war, so dwellings with bathtubs were very uncommon. It was a time when there was a lot of poverty. I liked manga, sure, but my main motivation was getting a bathroom. When I was in middle school, I liked gekiga*, and the most famous author was Takao Saito*, Golgo 13‘s creator, that unfortunately passed away recently. I loved his first manga that he drew when he was young. Out of admiration for him, I moved to Osaka since he came from that city. I’ve been hired by a company that was designing store signs, but that’s not really what I wanted to do in my life. A 20 minutes walk further than where I worked was where Takao Saito was drawing his kashion mangas. It was a two-floor building in very poor condition, and we could see Takao Saito and his editors working there. Frequently I would go there to say hello to them. Takao Saito was a precursor; he was one of the first creators to move to Tokyo, creating a whole manga production process by separating the roles. Also, do you know Sanpei Shirato*? He was the author of Kamui Den. Speaking about that production process, Shirato Sanpei, at the time, theorized something interesting about it. For him, there were three types of manga creators. Artists, craftsmen, and entrepreneurs. I would consider myself a craftsman.

Benjamin Daniel: Indeed, for me, you truly are the worthy heir of Takao Saito in terms of the stylization of gangsters, the underworld, and those virile figures of the 80s. You worked with many writers during your career, including Kazuo Koike, Buronson, and now Rîchiro Inagaki. What impresses you the most about each of them?

Ryôichi Ikegami: When I worked either with Koike, Buronson, or Inagaki, they were all at an age where they were the most efficient and mature at work. Their common point is that they are all pretty much massive-shaped men and very strong. Koike-sensei was a gekiga expert and knew when he was writing the scenario how to create scenes that would have a great impact when made as a drawing. On the other hand, what is impressive with Buronson is his use of foreshadowing, how to announce a situation and create a well-thought turnaround. He’s really good at it. He was saying about himself that he was a god of puzzles. To explain his scenarios, he compared them to jigsaw puzzles, where we had to position all the parts correctly to create the full image. He was often going on about how much he felt that he was a puzzle genius. Inagaki-sensei is good at descriptions. In his case, he draws the storyboards by himself. When I work with him, I receive already drawn storyboards. Even if he is a scenarist, he can draw very well, and the expressions on the storyboards are already very precise. Tsuge-sensei, who I greatly respect, said that once you make the storyboard, the manga is finished, and the rest is just simple work. So when I learned that, I asked my editor, “What do I have to do then? Just inking?”. But when I started to draw, I realized that interpreting someone else’s storyboard is actually different and even more difficult than just working with a script. I have to add feelings and expressions to the drawings of Inagaki-sensei, and that’s a difficult exercise.

Benjamin Daniel: That’s interesting. That’s why when I read Trillion Game, I felt the paneling differed greatly from your other works. Are there other scenarists that you would like to collaborate with?

Ryôichi Ikegami: Oh, you know, at my age… I already have a foot in the grave, so… I have trouble projecting myself into the future. However, I would like to adapt some Edogawa Ranpo* novels. That’s the kind of stories that I like. I have already adapted some of them that you can see in the exhibition. I would like to return to novel adaptations. There are also very ancient works made by the Nô* author called Chikamatsu Monzaemon* that I would like to adapt. Those are forbidden love stories about when you would die if you were seen with your lover. But what is interesting to me is that even with that risk, people were still seeing their lovers and making love. And for me, that’s extremely erotic; that’s the pinnacle of eroticism. You can’t make something more erotic than that.

Benjamin Daniel: And speaking of scenarios, do you have any projects where you would write the entire script or become a scenarist for another artist?

Ryôichi Ikegami: Yes, I have a personal project in mind. I already talked to my editor about it. Do you know Musashi Miyamoto? I would like to draw his story from a new perspective never seen before.

Benjamin Daniel: Incredible, just like Takehiko Inoue with Vagabond, who told his own view on the man. Your drawing style has become very precise and realistic over time. How did you improve your skills to draw such detailed pieces?

Ryôichi Ikegami: I think that’s thanks to the influence of literature. Before meeting Yoshiharu Tsuge, I only read popular novels that were not of particularly great quality. Those were the only novels I’ve read in my life. But Tsuge-sensei introduced me to classical literature, and thanks to that, I discovered a way of describing human emotions. For example, when I draw a face, I have to get in the head of the character; otherwise, it’s impossible to draw something right. That’s the influence of all those character descriptions that made me draw characters precisely and in detail. I draw, and I erase. I often redo the drawings many times before getting the expression that suits me the most. For example, when yakuza commit illegal actions, it’s not interesting to just draw them as evil people. I try to make them express some kind of sadness, whether it’s a trauma or a difficult family situation. That’s why sometimes, I change their glances a bit so that the reader expresses more empathy for the character. I’m not trying to glorify the yakuza but to talk about all those persons living at the margins of society, those who were excluded, and whom the only future society was giving was that of joining the yakuza.

Benjamin Daniel: Yes, we truly feel that tragic yakuza figure in your works, especially in Sanctuary, where the main character’s backstory is so sad and gruesome. About your style, you can draw human anatomy very well under any circumstances with a certain kind of eroticism and sometimes perversion that goes into the territory of the morally inappropriate. Where does that desire to draw morally wrong and taboo things come from?

Ryôichi Ikegami: That’s just my personal opinion, but I think that without morally wrong characters, you can’t get beauty out of eroticism. The smell of love and death are both really important. That’s exactly when I see real beauty; when both are mixed, they are two sides of the same coin. It’s Eros and Thanatos. There is a French novel that is famous for that written by the Marquis de Sade*.

Ryôichi Ikegami’s panel

This panel, open to everyone who had bought a ticket, was hosted by Xavier Guilbert, a French journalist specialized in manga.

Ryôichi Ikegami: Hello, everyone. Thank you all for coming here today to listen to me, even though it’s cold outside. And I would also like to thank everyone who participated in my exhibition at the museum. Now I will give my answers to your questions.

Xavier Guilbert: Thank you for coming here to Angoulême, Mr. Ikegami. You celebrated the 60th anniversary of your career in 2022, and like many Japanese people, you discovered your passion for manga as a child. That’s something you kept while becoming an adult, so I would like to ask you what attracted you to manga, what made you keep that interest, and when did you decide to make it your job?

Ryôichi Ikegami: I have spent my entire career drawing beautiful men and beautiful women, but as you see, I’m nothing like my characters. I am sorry [laughs]. But let me answer your question. I became interested in manga around 14 to 15 years after Japan lost the war. It was between the end of elementary school and the start of middle school for me. Very few homes were equipped with television sets at the time, so children were mostly having fun outside. What I had the most fun with when I was a child was when my big sister, who worked as a nurse, brought me a Shonen manga magazine once a month. I’ve always liked movies, but thanks to those magazines bought by my sister, I’ve learned to like manga. At the time, manga aimed at children mostly talked about hope, dreams, friendship, and all that stuff to re-motivate children. Reading them was stimulating. When I was very young, my father fell ill, so I was raised by my mother, and since I was a child, I was dreaming of buying a home for my parents. That idea came from the manga magazine my big sister was buying, in the reader’s mail, where there was a small article saying that if you become a mangaka, you could afford to build a house with a bathroom. Nobody has that kind of dream anymore, but that was my main motivation to become a mangaka. That’s the starting point.

Xavier Guilbert: You mentioned your father’s disease. That is what forced you to drop school at 15 years old and start working at a young age. You moved to Osaka and got a low-paying job painting store signs there. In that city, there was a lending bookstore network where you could find kashihon manga. You kept that desire to make manga, was that just for that motivation to buy a house with a bathroom, or was there something else?

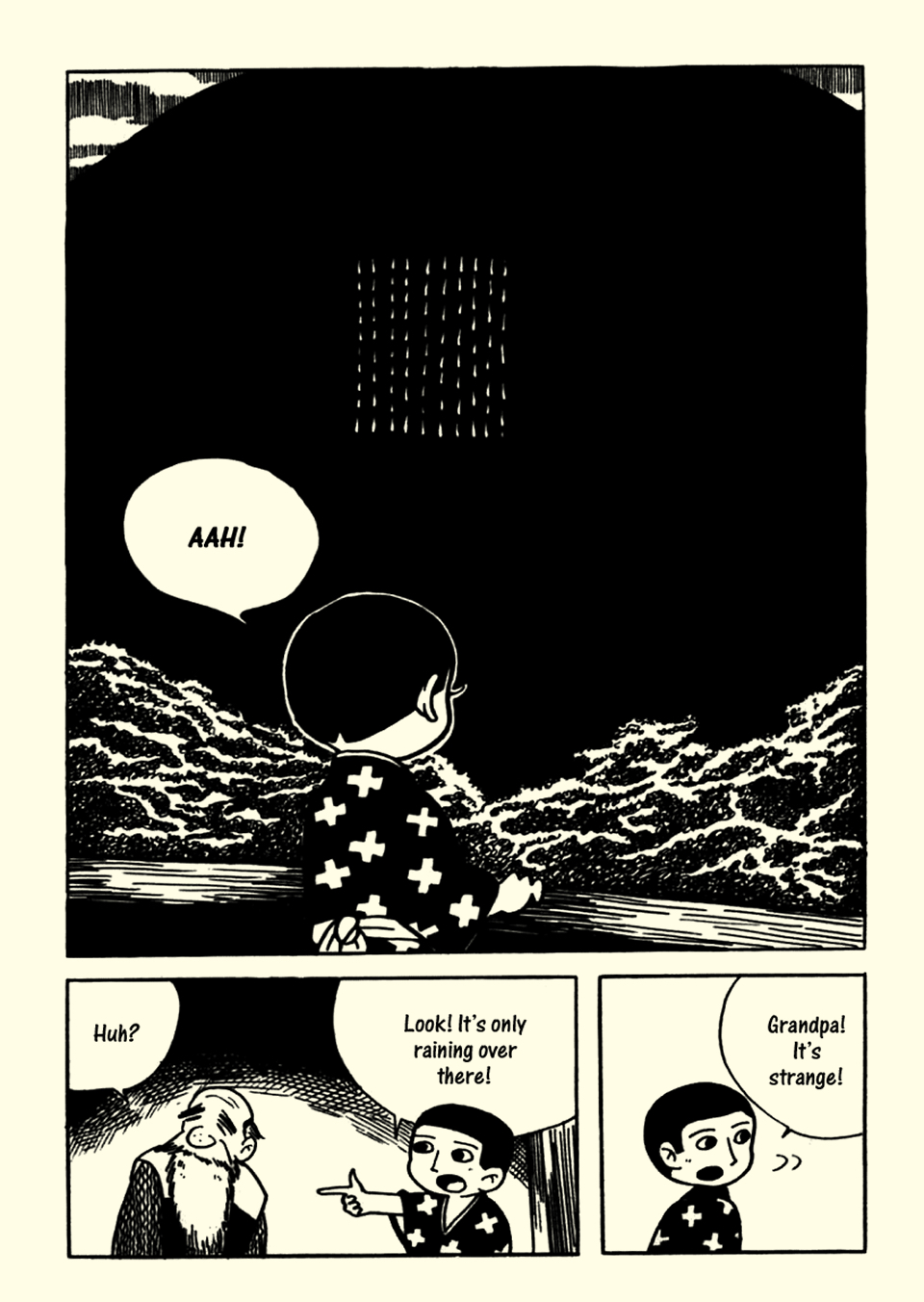

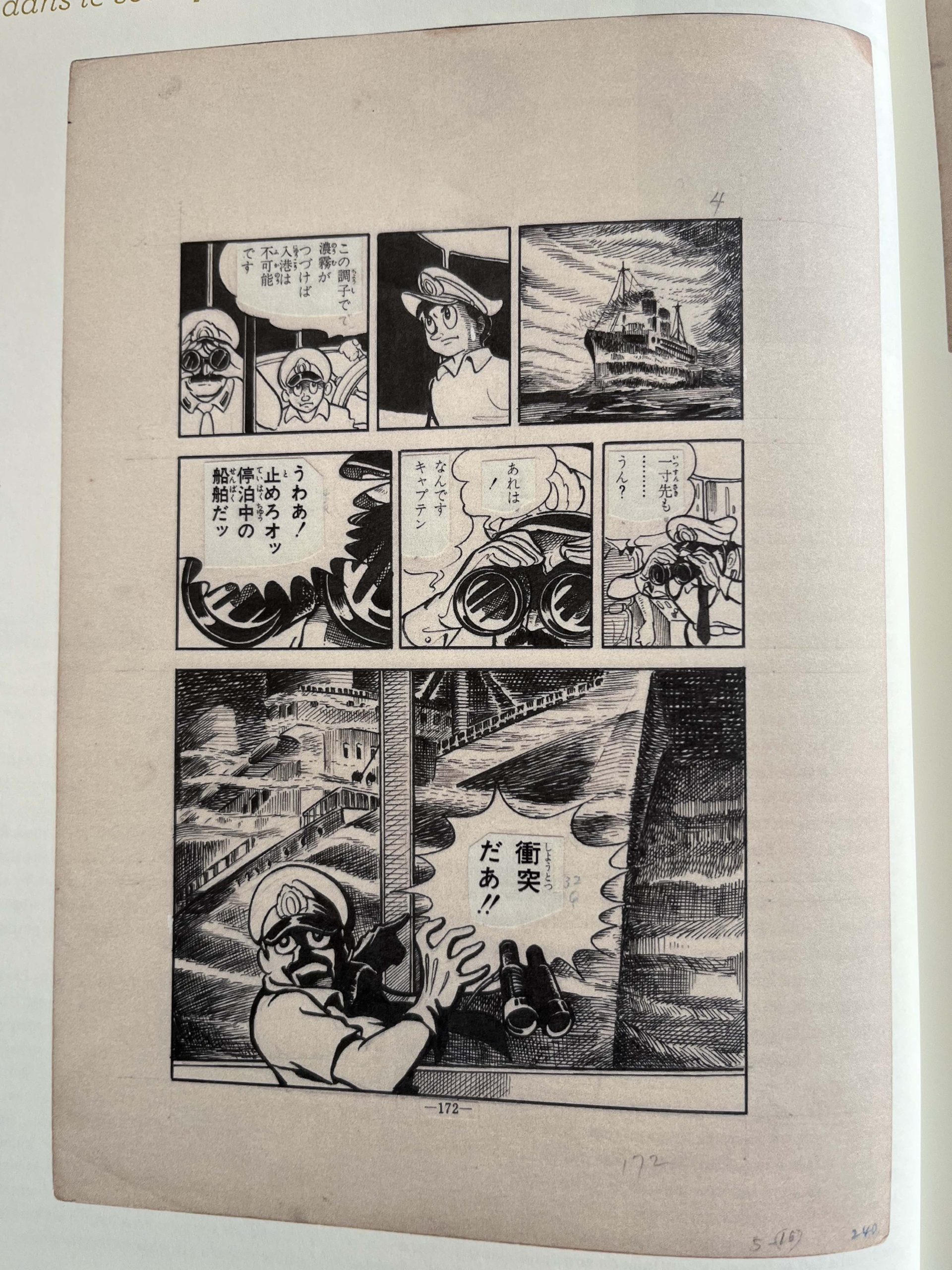

Ryôichi Ikegami: I was schooled in a field of study created to professionalize immediately. That was in Osaka, and that’s where I was introduced to a company that was making signs for stores and advertising. When I looked at that company’s address, I saw that it was around 20 minutes by bike from a publishing company. That was a kashihon manga publisher. They were manga that were lent for a modest amount of money. I wasn’t planning to spend my entire life in that store sign company, so sometimes, I ran away to the publisher to lend kashihon. That’s where I was able to meet and exchange with mangaka in small 6-tatami-sized rooms. That is very, very small. You have to imagine that this is where mangakas were drawing their manga. During the weekends, on Sundays, we would get yelled at by the neighbors as soon as we put the light on at night, so I was drawing with a futon on my head to hide the light. During that time, I have published three kashihon manga. You were paid 100 yen per page for it; at the time, a ramen bowl was 30 yen, so if you drew 30 pages, you would get 3000 yen. In my company, when you were working for 30 days, you would only get 9000 yen, so I thought that would be a great idea to get money. I was between 18 and 19 years old and thought I might get rich while doing this for a long time. But in those days, the kashihon manga world was already declining. Commercial publishers would spot kashihon mangaka artists and hire them. I was confident, so I thought about sending my resume to those commercial publishers, but no one ever answered me, and I wasn’t published in those big magazines. By dint of insisting, I ended up becoming an assistant for a mangaka that was a bit obscure, a bit forgotten, who had not managed to escape from kashihon. I had concluded that I wouldn’t be able to make a living through manga; I had almost given up. It was also in Osaka, in a very lively and popular district, we’re going to talk later about yakuza, but well, I just mention it to give a picture of what kind of district it was [laughs]. It was the golden age of yakuza. You could easily meet them in the street. In that district, I stumbled upon a magazine named Garo that I didn’t know about. In that magazine, Yoshiharu Tsuge-sensei was published. He was an author I liked, so I immediately sent them 18 pages of mine. The first Tsuge manga I read was named Hatsutake Gari, and the only characters are an old man and his grandson that would like to go mushroom picking and hope that the weather will be nice the next day.

There is a panel where you see the rain falling like on a screen, not drawn in all the sky. That struck me because I’ve seen in it an original way of expressing the boy’s hope that tomorrow would be a beautiful day. It’s a very short manga describing a child’s inner psychology. In Garo, there were also Sanpei Shirato, who made Kamui Den, and Shigeru Mizuki, for whom I worked as an assistant later. In Garo, I could read things I would never see in any other magazine I read while growing up. There were a lot of daily lives themed stories and, above all, more realistic ones. There were no forced happy endings, and authors could make anything they wanted. I found that it was new and refreshing; it impressed me. At the time, my life wasn’t easy, so classic children’s manga filled with hope started to sound fake to me, but a co-worker told me that I could make darker stories. That’s the first manga I made that was published in Garo.

It’s just an imitation of Osamu Tezuka for the drawings. Some time afterward, I received a postcard from Shigeru Mizuki. It was like a divine intervention. I had the feeling something was falling from the sky for me. The content of that postcard was, “If you want to become an author, come work for me.” I left my home at full speed, almost without saying goodbye to my store sign company, and I went to Tokyo right away. I think I could not look my co-workers in the eyes if I met them nowadays. [laughs] I didn’t play fair with them.

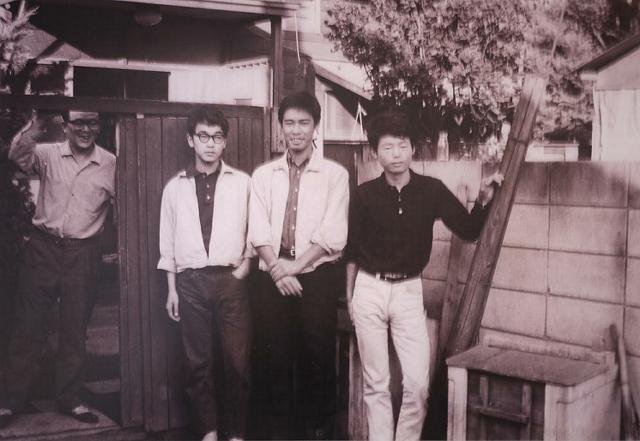

The ugly guy on the right is me! In the middle is Yoshiharu Tsuge, and on the left is Shigeru Mizuki, who was in his forties at the time. I was 22 years old. Gegege no Kitaro was starting its publication, and we worked a lot. But even though we worked long hours, I loved those times. I enjoyed working at Mizuki Pro because Tsuge came at least three times a week to the workshop, and for me, it was like a living God coming to work. In my previous company, my boss was only interested in earning money. But here, I saw other possible objectives for a company. I also remember that Mizuki-sensei had a very cute little girl who was always running in the workshop.

Xavier Guilbert: So you had this training period at Mizuki Pro, and we’ve seen before that you were introduced to literature with the teachings of Shigeru Mizuki and Yoshiharu Tsuge. You had a particular relationship with Yoshiharu Tsuge. Have you kept in contact with them, and what did you learn from them?

Ryôichi Ikegami: For Shigeru Mizuki, I wasn’t influenced by his drawings. Before I met him, I was a fan of Takao Saito, the author of Golgo 13, who was also from Osaka, that started at a very small kashihon manga publisher. I dreamed of becoming his assistant, but in the end, I became an assistant to Shigeru Mizuki, even though I had never read his manga then. I felt a little bad working for him without reading what he was doing. Therefore, I ended up reading his manga and was very impressed by his humor. It was tainted with some kind of nihilism. The first version of Gegege no Kitaro was Kitaro of the Graveyard, and there were very cool dialogues in it. At this moment, I realized I was going to work for a genius. But there was another genius: Yoshiharu Tsuge. I was a fan of everything he drew during the kashihon times. His stories describe the small joys and sadnesses of everyday life or the cruelty of reality, which he drew very gently. [points at him in the picture]

Look at him! Doesn’t he look kind? Yoshiharu Tsuge once said to me: “You must read literature.” I didn’t have much time to talk with Shigeru Mizuki because he was really busy. Near Mizuki Pro was a ramen shop, and Tsuge was sleeping upstairs. We often went there, the three of us, to Tsuge’s place. We were lying on very thin and hard futons, and the cotton of the comforter was leaking everywhere. We used to buy the least expensive cigarettes of the time and the largest Coca-Cola bottles, and while smoking and drinking those, we used to talk about literature. Apparently, Tsuge was very popular with women, so he talked a lot about girls.

I was able to get the remains of his conquests [laughs] and learn a bit about that, too, not just literature. Before meeting him, I was reading some pulp novels, but he recommended classic literature. Those are not very pleasant readings; for example, Dostoïevski or other Russian literature, it’s not very joyful. He was also recommending philosophy books or authors such as Ryūnosuke Akutagawa*. I started to read some of them, and that’s how I found out what could interest me. At that time, while working as an assistant, I was drawing my own manga on the side, and some of them were published in Garo’s columns. Critics from readers were good, but those were dark stories. One of my main issues at the time was that I wasn’t paid when I was published in Garo. I thought it would be difficult to get the house with the kitchen and the bathroom if it went on like this. But that’s when a bigger publisher spotted my manga, so I started to draw a Western. The person in charge admitted I was drawing well, but the story wasn’t yet well done, so he suggested that I start a new manga with a scenarist, Tsuji Masaki*, a famous author. That is what the start of my career looks like. There is still a lot to talk about. Do you want me to continue?

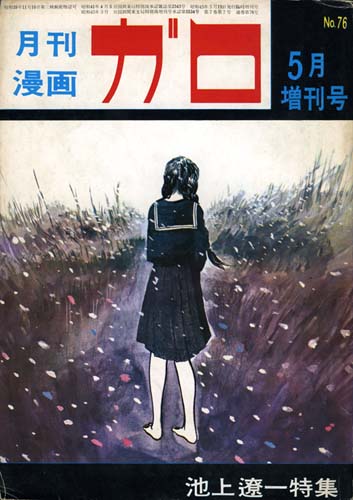

Xavier Guilbert: Here, we can see the cover of a 1970 Garo special edition dedicated to you. You said you weren’t paid. Was it the reason you left Garo, or were you searching for something else?

Ryôichi Ikegami: The high school girl on the cover is my teenage days’ first love. She was the most beautiful girl in the whole classroom. She was completely out of reach for a guy like me, so I made her into a character in a Garo manga called Winter Landscape. I loved drawing for Garo. I was often told that working for Garo was like masturbation. I don’t remember being paid once. I felt I needed to escape the magazine before it was too late. That’s precisely when other publishers started to contact me, and I was asked to make Spider-Man.

This picture is more beautiful because it was made later for reprints. That was made in 2002, and here is the 70s version. The person who contacted me to make that work was ten years older than me. In the beginning, I didn’t want to make Spider-Man because, for me, who drew in Garo, those superheroes with their big hearts weren’t inspiring to me. I found that forced, unrealistic, and not interesting. Because the real world was hard, I wasn’t a fan of those stories with the big villain losing at the end and all the good guys saved at the end, which is reality’s exact opposite. We can work hard and give everything we have we won’t necessarily make it. Therefore, I started turning down that offer, but the publisher put himself next to me and tapped me on the shoulder, saying that I was wrong because Spider-Man wasn’t at all what I imagined and that, on the contrary, he was a hero full of concerns and anxieties. That’s why he was asking me to do this job: because I was able to draw that more nuanced type of hero. And it convinced me to make Spider-Man. I don’t regret it at all. I liked it. My version of Spider-Man was often really dark. The chapters were 100 pages long. At first, I was writing the scenario alone, but then, we asked Kazumasa Hirai*, a famous SF author, to help me because I was having more and more trouble. He was also living in some kind of small shabby apartment. I went to his place and read the scenario proposals he had written for me. I found them fantastic.

What I learned from Hirai was that the dark side of the story can be a weapon and a form of entertainment that can target a large public. Entertainment wasn’t only reserved for positive and sweet stories. It gave me a lot of confidence, and I’m very thankful to Mr. Hirai. It was a turning point for me to transition from Garo to entertainment. It was immediately afterward that Kazuo Koike contacted me to work for him. It was when Golgo 13 started, and Koike was initially working as a scenarist for Takao Saito. Koike stopped to become independent, and he was searching for a young artist. In a sort of tabloid that wasn’t a manga magazine, we started a series called I, Ueo Boy.

There is a pun in the title, as he is a character that creates a desire for love. Because Koike-sensei had already worked for Takao Saito, he was a gekiga veteran. He was good at structures and staging. I learned from him about entertainment, staging, and catching the reader’s attention. I, Ueo Boy was a complicated publication because Koike-sensei was going back and forth between three different magazines. It was a magazine addressed to adult males in a much larger format than most magazines. It was much more violent than my previous works, as readers were young adult males, so the concept was a bit like “Let’s just make porn; it’s going to sell.” In the story of I, Ueo Boy, the main character once goes to the USA to get revenge, and he gets chased by killers, but every time, he gets saved by a beautiful American girl and has sex with her. For the Japanese readers of the time, that was awesome. It was like a dream. Japanese young men couldn’t even imagine touching an American girl with their fingers. This manga had a very cathartic side, and it was a success. Because the magazine was larger, I had to adapt my drawings to make them more realistic. It was the time when Bruce Lee was starting to get famous. At the same time, while I was doing this porny series with American girls, I was working on Otokogumi in another magazine. Since Koike-sensei was very busy, he always turned in his scenarios late.

I had to finish 16 A3 pages in 3 days, so obviously, I was forced not to sleep. Otokogumi was a series published in a weekly magazine, so here I was also forced not to sleep! Every week I had to do all-nighters. There were no exceptions. During those times, my assistants started getting sleepy, so they bought a medicine called “Moka.” For one hour, you were awake, but only for an hour! After that, we were all sleepy again. Those were roughly the working conditions for Otokogumi. When I saw my drawings at the exhibition yesterday, I remembered all of this…

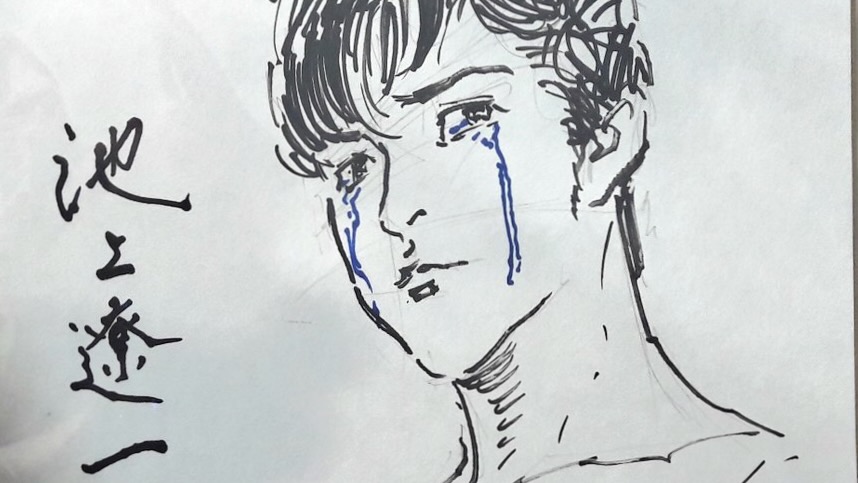

After that, my next collaboration with Koike-sensei was Kuzuoibito. After that, I started Crying Freeman. Kizuoibito was made during the rise of the Japanese economic bubble. Those were crazy times. Even people with low-paying jobs went golfing. Imagine a time when everyone was earning three times more than their previous salary. That’s why heroes were becoming very, very muscular like this. It’s not the same musculature as in I, Ueo Boy. After that, I started Crying Freeman, but that was after the economic bubble burst. Crying Freeman‘s proposal was made by telephone. Koike-sensei called me, which was very unusual to hear him so excited on the phone. He pitched me the project like this “You see, there’s a hero. He’s a killer, but every time he kills, he cries!”. You might think this was a joke, but not at all. When he pitched that crying killer image, I immediately thought the hero must be very beautiful. If you have a very ugly killer that is crying, nobody will identify with him! From then on, I dedicated myself to drawing handsome men. My aesthetic research oriented itself toward beautiful men. The starting point was Crying Freeman. In this continuity, I started to work with another scenarist called Sho Fumimura on Sanctuary, which was a great success. I also drew Sanctuary with that desire to draw beautiful men that I got while working with Koike-sensei. That’s the story of two young men that grew up in Cambodia during the killings of Pol Pot. The main characters have experienced in their flesh the terror of that period of Cambodia’s history. They were forced to do unthinkable things to survive even though they were still children. Those characters eventually arrived in Japan, and they didn’t understand how people could be so slack in front of politics and scandals. The youth was indifferent to all the scandals that shook the political world. It outraged them; one became a yakuza, and the other a politician to change things. This is a buddy manga. At the time, the worlds of yakuza, business, and politics were very close and worked together a lot. The largest yakuza organizations moved incredible sums of money. Hojo, the one who becomes a yakuza, is a very intelligent character, but that is basically Sho Fumimura’s own intelligence. He does the dirty work and gives the dirty money to his friend Asami who became a politician. To be honest, what Hojo and Asami are doing is just the basic functioning of capitalism. Even nowadays, people are still very unaware of what is really happening in the background, even though, thanks to the internet and social networks, people are starting to get more aware of political affairs and scandals, especially the youth. But indifference is unfortunately still prevalent. Most people don’t feel concerned at all. I think that the thematics of Sanctuary are still relevant nowadays. I cried while drawing the end of Sanctuary. If you don’t want to hear the end of Sanctuary, cover your ears [or skip a few lines] because I will spoil it! One of the two characters is sick, and they meet in Cambodia at the end. Asami asks Hojo if he can sleep on his shoulder. Then I couldn’t resist but cry at this scene. The tears could not stop flowing. That was the first time I cried while drawing; I never felt that before.

Xavier Guilbert: And that is one of the first boards with which we open the exhibition by a rather particular chance.

Ryôichi Ikegami: Thanks for your selection. Nowadays, I work with Rîchiro Inagaki on Trillion Game, but between Sanctuary and now, quite a few years have passed. Do you have any more questions?

Xavier Guilbert: You already answered many of my questions [laughs]. I was going to ask about your work with Mr. Koike and the evolution of the body’s representation. I also wanted to ask you about something: I feel you like to add drawings to the drawings. For example, tattoos are very prevalent in your works and are drawn onto drawn bodies. We can also find this element in your approach to fashion with very beautiful patterns drawn on kimonos and even things like pottery. Is there a real artistic pleasure in that kind of thing?

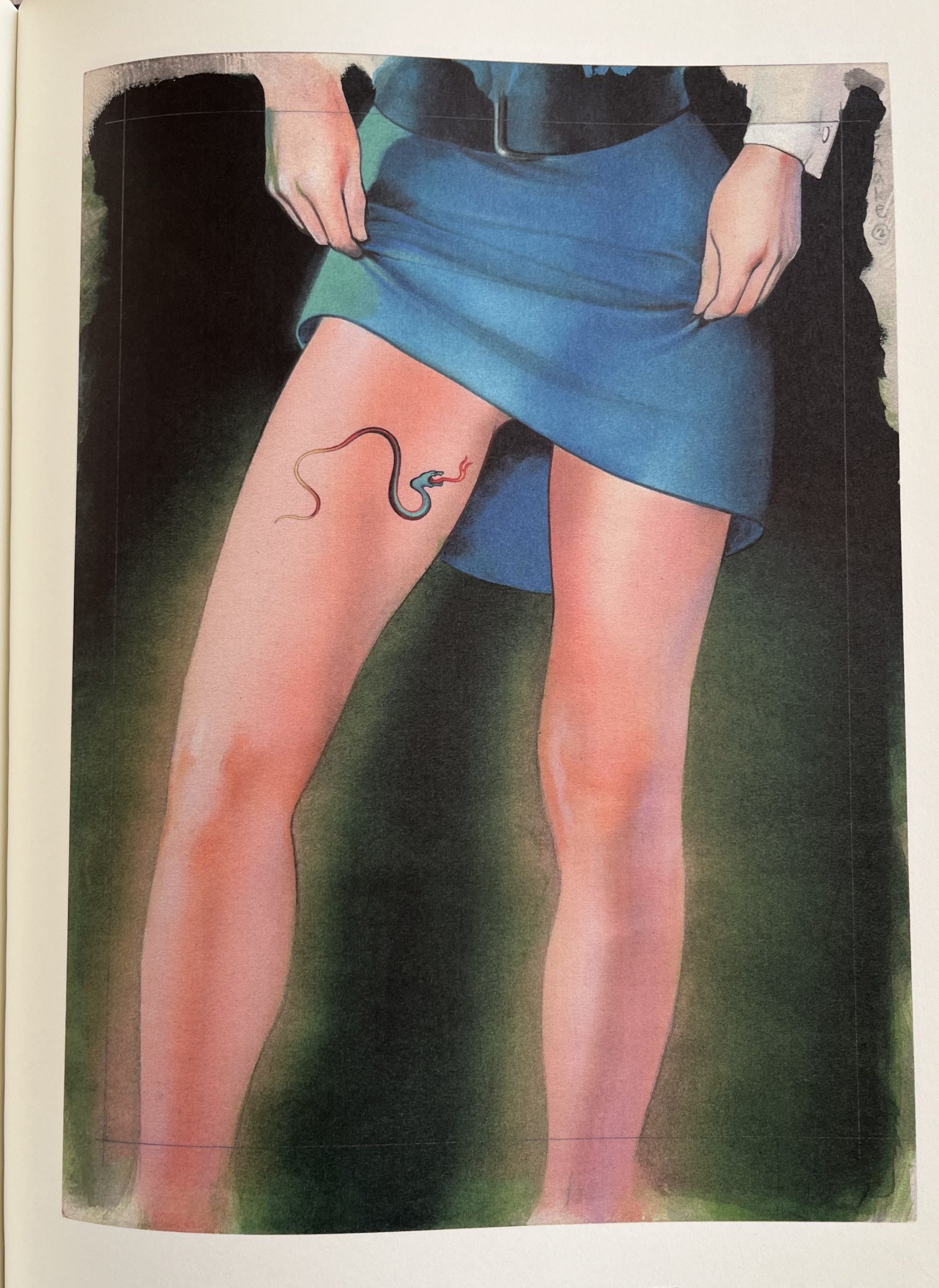

Ryôichi Ikegami: The page from Crying Freeman with the tattoo that can be seen in the exhibition was an idea of Koike-sensei. We both like tattoos in general. In the district where the store sign design company I was working, south of Osaka, you could find cabarets and public baths. After work, we used to go to the public baths, where you could find yakuza. They were all very well-built and well-muscled, with absolutely gorgeous tattoos on their bodies. The patterns were often Buddhist guardian figures. The fat Buddha suited people well with plumpness. I like how the face goes well with the flesh that is moving. I was looking at all that, lost in my thoughts [laughs]. That’s when they went to me asking me if I wanted to work for them. The pay was at least 20000 yen per month. I said, “Sorry, I… I will think about it…”. That’s to give you a rough idea of that time. I really like the snake and woman combination. Doesn’t that make you feel good? [laughs] It’s a bit erotic. Well, more than just a bit.

Xavier Guilbert: That illustration comes from your short story, in which you are also the scenarist, which is called The Snake. A woman has a snake tattoo on her thigh, and there is a whole erotic play around that.

Ryôichi Ikegami: I won’t go into detail about it [laughs]

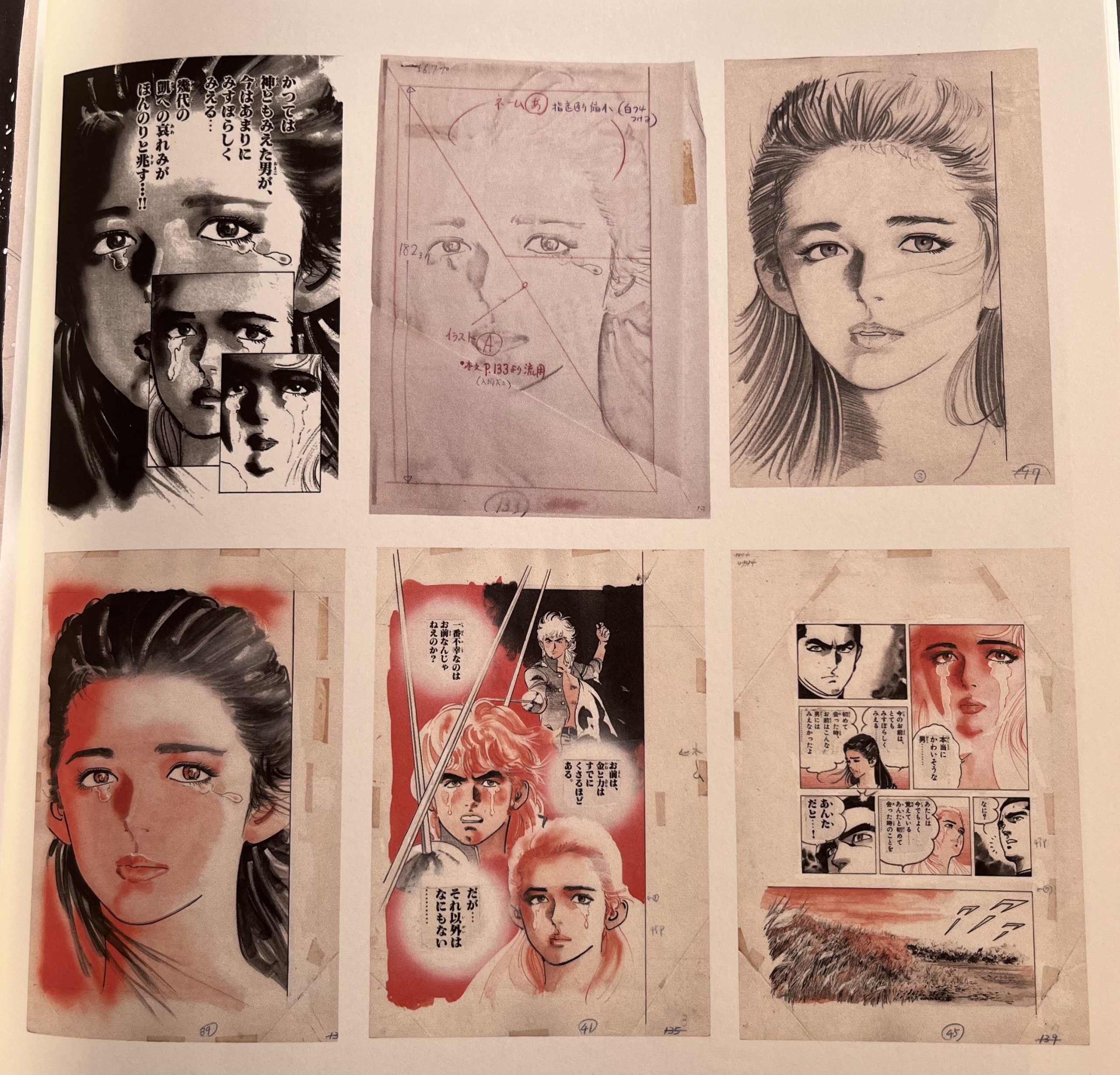

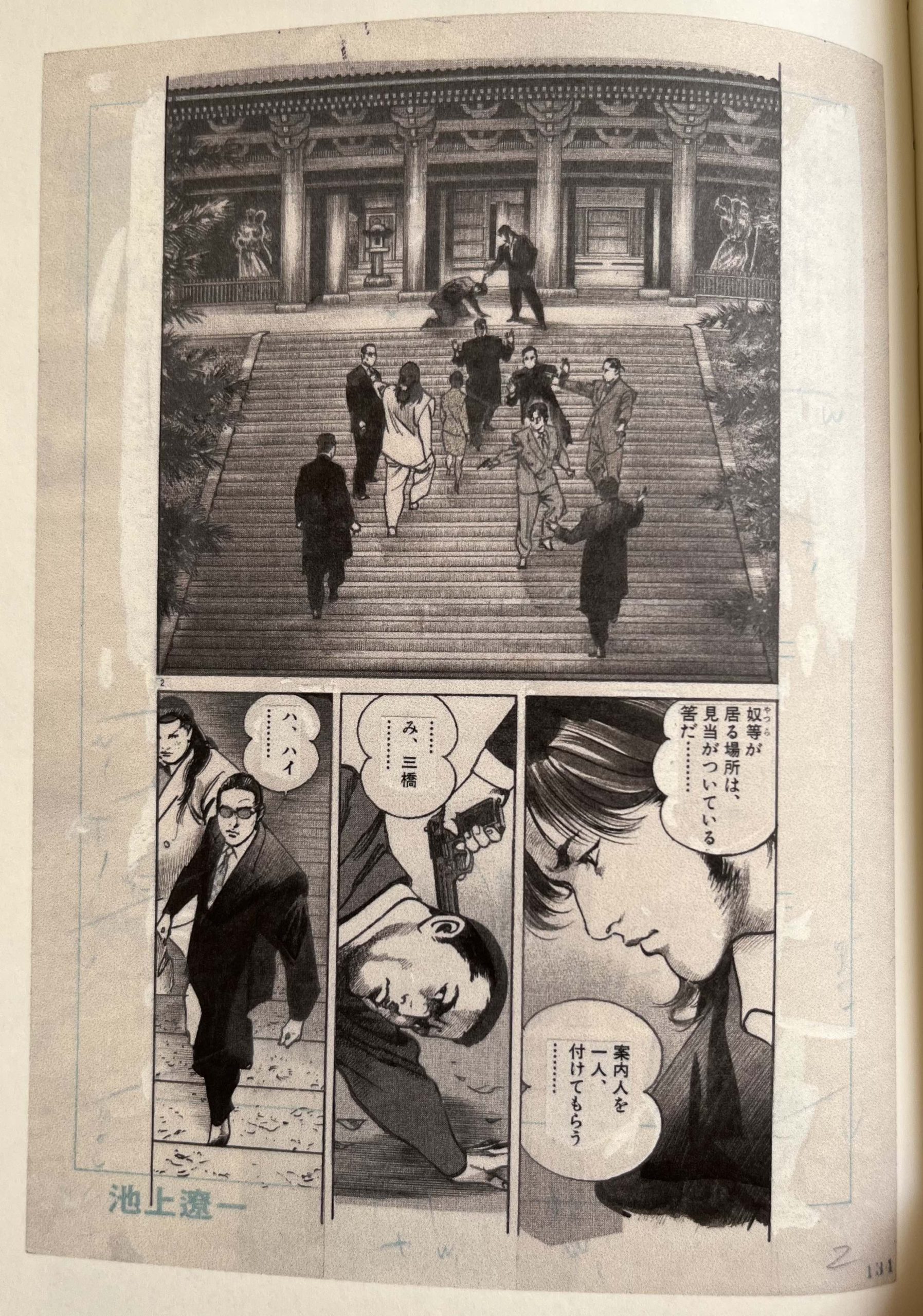

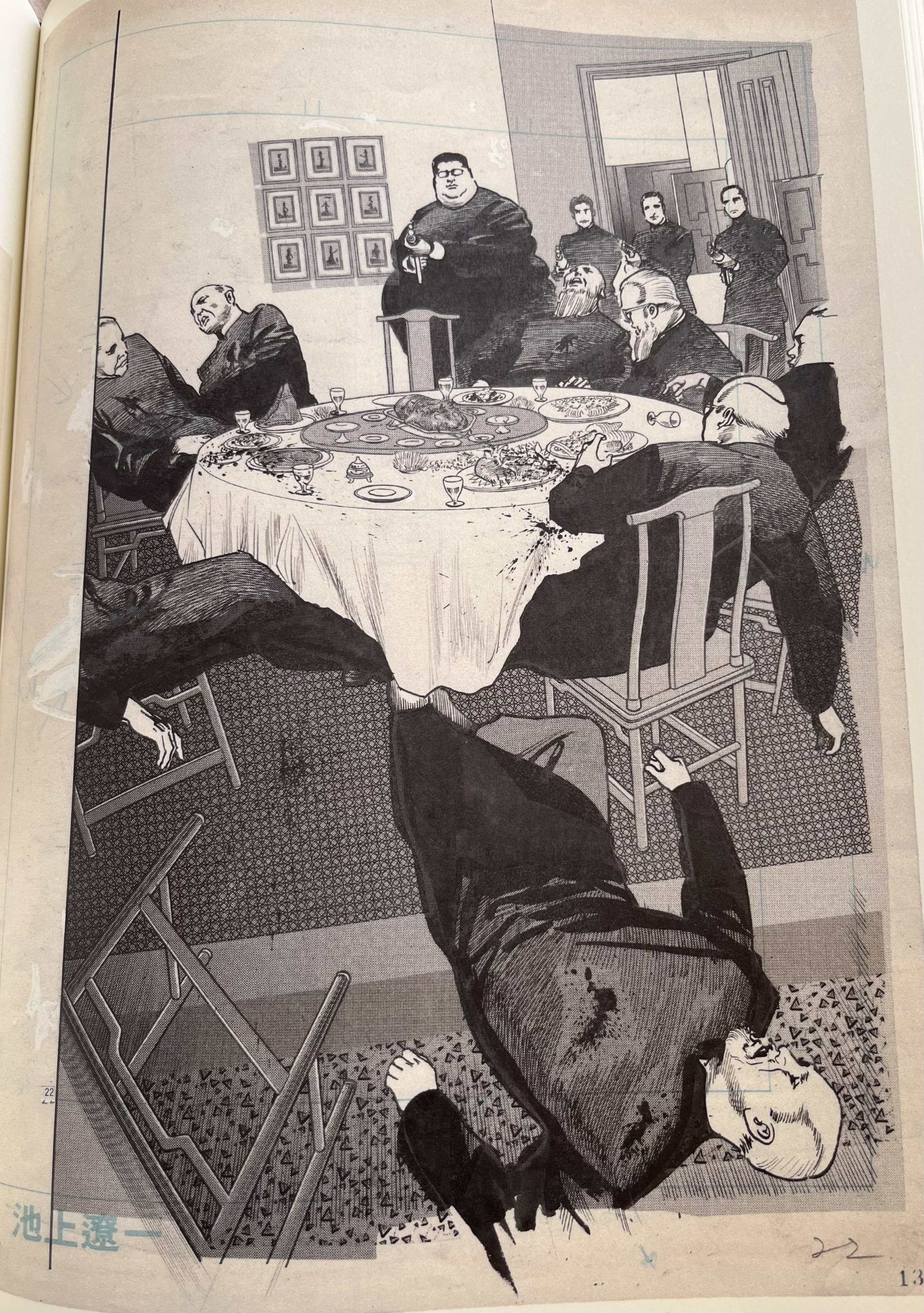

Xavier Guilbert: There is also your relationship to composition that I want to talk about. In the exhibition, we can find those boards that are a happy accident of the selection because we just asked for the board on the left, and we were told that it doesn’t exist and that it was a composite of all the boards we can see on the right. What’s your composition process? I have selected other ones, like this one from Heat, which is a bit like The Last Supper but in a triangular shape with a central character on the top and a bunch of lines of force. Where does that focus on composition come from?

Ryôichi Ikegami: In manga, there are drawings but above all, there is a story. When I read a scenario, I try to imagine how I could stage it. I watch a lot of movies, and that is what gives me ideas for scenes. That this moment should be shot from above or from the bottom, and so, without a scenario, I would be unable to draw such compositions. A manga drawing must fit the story, paneling, and panel composition. For example, in Shonen manga, everything is drawn from a child’s point of view, so you see a lot of compositions as if it’s seen from the bottom. The angle is often a bottom angle, like a child looking at his father. If you grow up in a house as a child, it feels very narrow when you return as an adult.

How we see the world changes with age, so we must adapt the drawings according to who looks at it. Two times a year, I teach at an art university in Osaka. I try to explain to them that there are many ways to see the world that are invisible to us in our everyday life. Some animals see infra-reds and not humans. For them, the world is made of infra-reds. When you have discovered those invisible worlds, you can use them to make people laugh. Talent is the ability to discover those things. Humor is often based on things you never realized in your everyday life, and the first time you spot it, you laugh about it. Japanese comedians don’t have particularly interesting lives themselves, but they will make people laugh while telling the small unconscious habits of a taxi driver, their fathers, etc. It’s so much part of our daily lives that we don’t pay attention to it. But artists and scenarists of talent notice this type of thing. It’s the difference between the common man and the genius. Personally, I’m just a common man [laughs].

Xavier Guilbert: Before talking about your last work, Trillion Game, since you worked a lot with Mr. Koike and Buronson, I wanted to ask what is your favorite work among everything you worked on, and if there is one of them that you particularly regret?

Ryôichi Ikegami: When you have a career as long as mine… It can seem a bit pretentious since I’m not a scenarist, but… I’ve made a lot of manga under the direction of a publisher, but as an artist, you can be a bit frustrated sometimes because you end up falling into a routine in such a series. The scene may be different, but the turns of events are similar. And the characters can also go out of style too quickly. When you have a career as long as mine, there are a lot of manga like this in your career. But if you want me to talk about the works I’m proud of: I, Ueo Boy, Otokogumi, Sanctuary, Crying Freeman, and Nobunaga. I do not include Trillion Game since it’s not finished yet! The main characters still have to achieve their goals and make tons of money.

Xavier Guilbert: Precisely, we are now going to talk about Trillion Game! Not only do you work with a new scenarist, but it’s also the first time in your career you have to follow a storyboard made by Mr. Inagaki. What made you work on Trillion Game? Was this a new challenge for you because it’s a very different manga from your other works?

Ryôichi Ikegami: Before Trillion Game, I had worked with Mr. Inagaki once on a series called Kobushi Samurai. But like I already told you, normally, I’m used to working with written scenarios. But for the first time, with Mr. Inagaki, I work with already drawn drafts that are nearly finished drawings. Yoshiharu Tsuge, whom I admire, often told me that when you have made the storyboards, you have decided on the paneling, the manga is completed, and inking is not that hard after that. For Tsuge, that step was the most important of the whole process. It’s like giving birth to a baby. I think the same. When you have made the storyboard, the manga is already done, so I told Inagaki, “What is left for me to do? Do I just have to ink it? Will I just have a technical role?” My editor, Mr. Yamazaki, who is here with us in the back – and a beautiful young man, told me I was mistaken. Mr. Inagaki is still young; he is in his forties, and his way of making storyboards is very dynamic. His drawings, too, feel very youthful and fit the current times. I made a series called Begin, also with Mr. Yamazki as my editor, and I drew male characters in a very realistic way, so I wasn’t sure my style would fit a story like Trillion Game, so I politely refused. Yamazaki looked at me with really sad eyes… He told me I was mistaken, and it was precisely my realistic style mixed with Inagaki’s youthful, dynamic writing style with a lot of humor and gags that he aimed at. He was sure that combining those two styles would give a very interesting chemical reaction as a result. This argument did not convince me. At my age, it would surely be the last series I would make in my life, but I accepted. My editor was right, the chemical reaction really occurred, and the series is a big success! I find it much more difficult to work with storyboards than with a written scenario. I had to adjust my style to Inagaki’s universe and couldn’t draw like usual. For example, I had to draw female characters’ faces that are not really my type. All female characters I’ve drawn until now are tough women with piercing looks in their eyes. Maybe I’m a bit masochistic; I’m very attracted to strong women! You should see my wife. She is truly frightening… Inagaki’s female characters are sometimes tough too, but when they get angry, they have lovely faces. They stay cute! So I see those storyboards, he asks me to draw those kinds of faces, and I have to interpret it to my style. I must make it more realistic, but don’t you think his version is better? You feel many emotions in those rough storyboards; you can feel involvement. I feared this energy would be lost after adapting it to my techniques. It’s still the case when I work on it. I’m often worried about interfering with the work of Mr. Inagaki. I learn a lot from him, and sometimes it even keeps me awake at night. But my editor and Mr. Inagaki cheer me up and give me courage. I am lucky that I am very well supported. I’m unaware of the whole story, so I can’t wait to see what happens next in Trillion Game‘s scenario! It’s a series set in the business world, and it looks a bit like Sanctuary because it’s a story about two friends, a buddy manga. And it’s not the only similarity they share. The intelligence of the main character Haru and his sociability are very much like Hojo. The second main character Gaku, the computer guy that looks like an otaku, is very talented at computer science in general. He is a genius engineer. Those two characters create a plan to achieve their goal of earning 1 trillion dollars, and in the middle of that, it’s a story filled with humor. Like Sanctuary‘s main character, Haru is a very good liar and spends his time scamming rich adults. He gets tons of money thanks to that. Actually, that’s what all politicians and big company bosses are doing on a daily basis. I think it’s a bit like that in all countries, right? It’s a manga about brats provoking and hacking that capitalist world of adults. Times might have changed since Sanctuary, but I think there is a real common point to go against our society’s current system. It’s not really that I approve of that kind of manners, but I think that’s a good way to criticize society. That is my own interpretation of Trillion Game, so honestly, I don’t know why I refused at first! It’s a manga with as much potential as Sanctuary, and I didn’t realize it at first. I hope to stay alive until the end of the series…

Xavier Guilbert: Since you talk about declining it at first, how do you look back on your career? If there was something that you wish you had done differently, what would it be? And what would you say to the 1962 version of yourself? What kind of advice would you give to him?

Ryôichi Ikegami: I think the most important thing is to find for yourself a unique weapon that nobody else has but you. It can be anything. You have to find that unique thing inside yourself, take care of it, and grow it. This photo is from the time I was making Spider-Man. What I’d like to tell him… Well, I don’t have any advice to give him. During that time, my father was sick, and I was away from my mother. I had nobody I could rely on. I set out on my own… Well done, kid! [laughs] That’s about all I’d have to say to him.

Xavier Guilbert: I think we have time for one or two questions from the public!

Florian Abbas for fullfrontal.moe: While reading Crying Freeman, I was struck by the fact that Western characters had particular facial features. I was wondering if real-life actors and actresses inspired them. What are the actors, actresses, or even films that influenced you during your career?

Ryôichi Ikegami: It is very common that I find inspiration in Hollywood actors and actresses… particularly for drawing very sexy men. For the shape of the lips, the bridge of the nose, eyes, ears, muscles… To draw all of that in a sexy way, I study by small parts. In a movie with Tom Cruise, Rain Man, there is a scene where the two brothers are talking to each other in a car, with a close-up of Tom Cruise’s lips, who is speaking very quickly. And I found it reaaally sexy… I recommend this scene from Rain Man. I think it’s even sexier than if it was a scene with a woman! I often use these kinds of details in my manga. For example, I love Clint Eastwood in his westerns, when he was in his thirties and staring at the desert, squinting his eyes like this… He also has a beautiful nose bridge and a nice beard shape. About beards, there are a lot of men with really beautiful beards here at Angoulême! [laughs] It makes me envious! That’s the kind of detail I pay attention to and try to transcribe into my drawings. Also, there is a Hollywood movie with Burt Landcaster… Ah, you are all too young; you might not know about him! [laughs] There is a scene where he walks from behind that is very sexy… The way his ass is moving… I don’t even remember what the film is talking about or even the title. I just remember Burt Landcaster’s ass. [laughs] Well, I think I might be a bit of a pervert.

Xavier Guilbert: Well, I think that marks the final word of this panel!

Notes

Jômon Period: In Japanese history, the Jômon Period is the time between 14000 and 300 BCE when Japan was inhabited by hunter-gatherers and agriculture was starting to appear. It is very much known for its very particular-looking pottery and statues, which had a lot of influence on contemporary popular culture, like Arahabaki from Shin Megami Tensei or Phobos from the Darkstalkers series.

Yoshiharu Tsuge: (1937-) Mangaka and essayist, he is an extremely influential artist of the gekiga movement. He started in the kashihon manga industry but was later mostly known for his works in the famous Garo magazine. His life was very eventful, making a lot of trips across Japan that inspired him for his works, but he faced several hard periods of depression with suicide attempts. Some of his most notable works include Nejishiki, Akai Hana, and Munô no Hito.

Kashihon: A Japanese term describing books that are rented out by people in rental services. The market really exploded after World War II, and a lot of famous manga artists started their careers while doing kashihon manga, such as Osamu Tezuka and Shôtarô Ishinomori.

Garo: (1964 – 2002) A cult monthly manga magazine founded by Katsuichi Nagai and published between 1964 and 2002. It was specially made to publish gekiga artists who didn’t want to work for mainstream manga magazines, particularly Sanpei Shirato, who published his Marxist manga Kamui Den in Garo. The magazine was very influential and is often described as a fundamental historical point of the development of alternative avant-garde manga. In response to the success of Garo, Osamu Tezuka himself created the magazine COM.

Shigeru Mizuki: (1922-2015) Very influential manga artist, especially known for Gegege no Kitaro, and a specialist in yôkai horror manga. He is also known to have been sent as a soldier by the Japanese Imperial Army during World War II, during which he lost his right arm, contracted malaria, and saw every aspect of the horrors of war. He made an autobiographical manga mixing reality and fiction about that war experience.

Tetsu Kariya: (1941-) Manga writer and essayist who have worked multiple times with Ryôichi Ikegami on Otokogumi as well as Otoko Ôzora. He also wrote the immensely popular 111-volume long food manga Oishinbo.

Kazuo Koike: (1936-2019) Extremely famous manga writer and novelist. He is one of the most prominent figures of the gekiga movement. He started his career serving as a writer for Takao Saito’s Golgo 13. His works include Lone Wolf and Cub, drawn by Goseki Kojima, Lady Snowblood, drawn by Kazuo Kamimura, and Nijitte Monogatari, drawn by Satomi Koe. He also happened to be a lyricist and wrote the lyrics of the famous openings of Mazinger Z and Great Mazinger.

Noboru Kawasaki: (1941-) Manga artist mostly known for his incredibly influential baseball manga Kyojin no Hoshi, published in Kodansha’s Weekly Shonen Magazine and co-written with none other than Ashita no Joe author Ikki Kajiwara. His work has changed sports manga forever.

Shô Fumimura: (1947-) Manga writer, by his real name Yoshiyuki Okamura, he is also known by his other nickname Buronson. He is mostly known for the classic best-seller Hokuto no Ken, drawn by Tetsuo Hara, and has worked multiple times with Ryôichi Ikegami. He also participated in the start of the career of Berserk’s author Kentaro Miura by writing some of his first works, Ôrô and Japan.

Rîchiro Inagaki: (1976-) Manga writer famously known for very successful Weekly Shonen Jump series such as Eyeshield 21, drawn by Yusuke Murata, and Dr. Stone, drawn by Boichi. He is currently writing Trillion Game for Ryôichi Ikegami.

Jean Henri Gaston Giraud, aka Moebius: (1938 – 2012) French artist, cartoonist, and writer. Esteemed by many artists and filmmakers, he is one of the most influential comic and Science Fiction artists. His illustrations for Alejandro Jodorowsky’s unproduced adaptation of Dune as well as his series The Incal, are essential pillars of modern Science Fiction.

Gekiga: Literally “dramatic pictures,” it is a manga movement that is described as a response to the dominance of mangas aimed at children led by Osamu Tezuka in the 1950s. It is marked by his more mature and realistic themes and aesthetics defined by sharp angles and gritty lines. Notable gekiga artists include Takao Saito, Sanpei Shirato, Kazuo Koike, Goseki Kojima, and Ryôichi Ikegami.

Takao Saitō: (1936-2021) Very famous and prolific manga artist mostly known for the Golgo 13 series, which is the longest manga ever, with 208 volumes published in 2023. Takao Saito died in 2021, but his wish was that Golgo 13 would still continue without him. He is one of the most notable gekiga artists and has always rejected the term manga to describe his works, preferring the term gekiga.

Sanpei Shirato: (1932-2021) Very influential manga artist and essayist, his most important manga Kamui Den was the first series to be published in the Garo magazine. Sanpei Shirato was a pioneer of the gekiga style, and his works are known for their strong social criticism as they include a lot of Marxist thematics.

Edogawa Ranpo: (1894-1965) Novel writer who played a major role in the development of mystery and thriller fiction in Japan. He was very influenced by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in his most famous work, the Private Detective Kogoro Akechi series. His real name is Taro Hirai, and his pen name is a rendering of Edgar Allan Poe’s name in Japanese.

Nô: A traditional Japanese theatrical art and also one of the oldest extant theatrical forms in the world. Unlike most Western theatrical arts, nô performers are not actors but rather performers and storytellers who use their visual appearance and movements to suggest the essence of the tale rather than to enact it. Nô integrates costumes and dances requiring highly skilled performers. nô‘s most iconic trait is, without a doubt, the masks performers use to describe various types of characters, men and women but also monsters of Japanese folklore.

Chikamatsu Monzaemon: (1653-1725) Dramaturgist and poet who wrote more than 130 plays during his lifetime. He has practiced many forms of Japanese theatrical art, such as nô, kabuki, and bunraku. He is often qualified as the “Japanese Shakespeare” and is considered the greatest dramaturgist of Japanese history.

Marquis de Sade: (1740-1814) French novel author and philosopher that has devoted his life and works to eroticism and pornography associated with cruelty and unethical acts such as torture, rape, and incest. His works were very ahead of their times, and he lived 27 years of his life locked up in the Bastille prison and was released during the French Revolution. His most iconic work is Justine (Les Infortunes de la vertu), also known as Les Deux Beautés. Napoleon Bonaparte described it as the most abominable book that the most depraved imagination had produced and put Sade in an asylum, where he died after 13 years.

Ryūnosuke Akutagawa: (1892-1927) Very influential Japanese novel author and poet, regarded as the father of Japanese short stories. He has brought to Japan a lot of influences from Western authors such as Baudelaire, Anatole France, and Mérimée. He committed suicide at 35 but has published more than 150 works during his short life from very various genres such as mystery, fantasy, and social satire. His novel In a Grove was adapted by Akira Kurosawa in his famous movie Rashômon.

Tsuji Masaki: (1932-) Extremely prolific Japanese anime writer that produced scenarios for episodes of many classic series of anime history. The list of series he worked for is endless and includes Astro Boy, Kimba the White Lion, Star of the Giants, Cyborg 009, Doraemon, Dr. Slump, and many others.

Kazumasa Hirai: (1938-2015) Novel author and manga writer known for his science fiction work. He is the creator of 8 Man as well as Genma Wars, which was adapted by Rintarô with character designs from Katsuhiro Ôtomo in the famous animated movie of the same name.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Oshi no Ko & (Mis)Communication – Short Interview with Aka Akasaka and Mengo Yokoyari

The Oshi no Ko manga, which recently ended its publication, was created through the association of two successful authors, Aka Akasaka, mangaka of the hit love comedy Kaguya-sama: Love Is War, and Mengo Yokoyari, creator of Scum's Wish. During their visit at the...

Benoît Chieux, a career in French animation [Carrefour du Cinéma d’Animation 2023]

Aside from the world-famous Annecy Festival, many smaller animation-related events take place in France over the years. One of the most interesting ones is the Carrefour du Cinéma d’Animation (Crossroads of Animation Film), held in Paris in late November. In 2023,...

Directing Mushishi and other spiraling stories – Hiroshi Nagahama and Uki Satake [Panels at Japan Expo Orléans 2023]

Last October, director Hiroshi Nagahama (Mushishi, The Reflection) and voice actress Uki Satake (QT in Space Dandy) were invited to Japan Expo Orléans, an event of a much smaller scale than the main event they organized in Paris. I was offered to host two of his...

Trackbacks/Pingbacks