Atsushi Kaneko is a manga author born in 1966 who started his career in the 1990s. Almost all of his works are published by the Enterbrain magazine called Comic Beam. He is often described as a punk, with the intention of destroying everything he passes. And you can say he is quite an impactful author, creating strong and freaky characters with weird haircuts who often kill a lot of people.

But it would be reductive to talk about his works like that. When you read his mangas, you can see the great manga artist he is, brilliantly blending influences to create this unique art style that looks so explosive at first sight but is actually very clean.

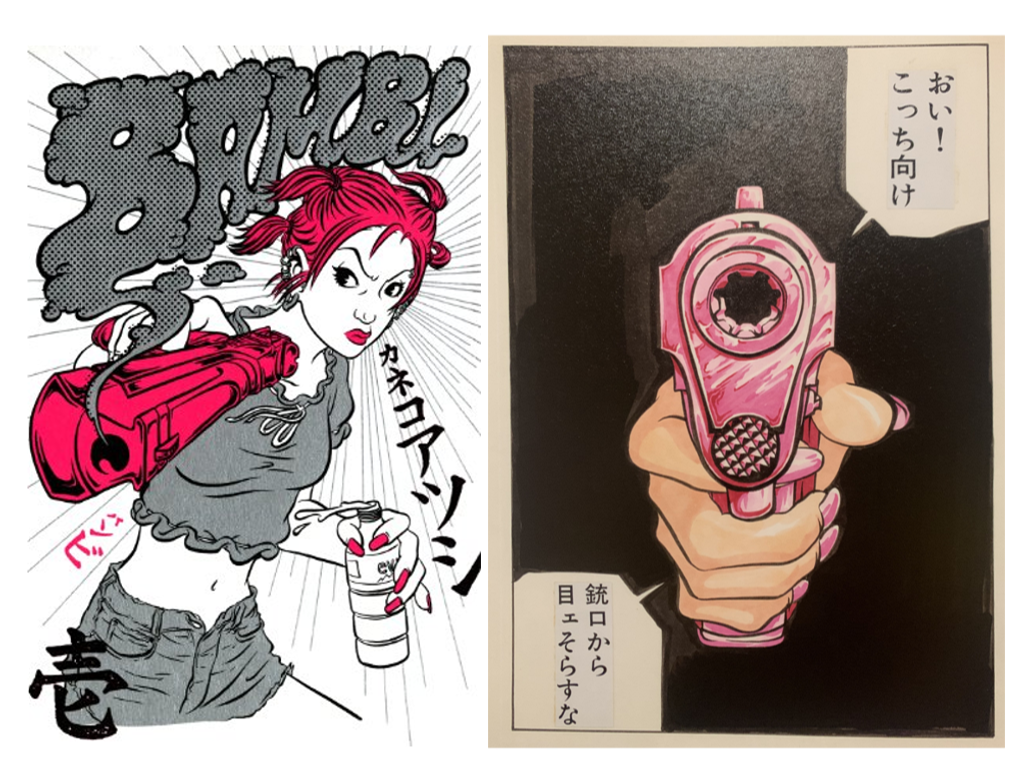

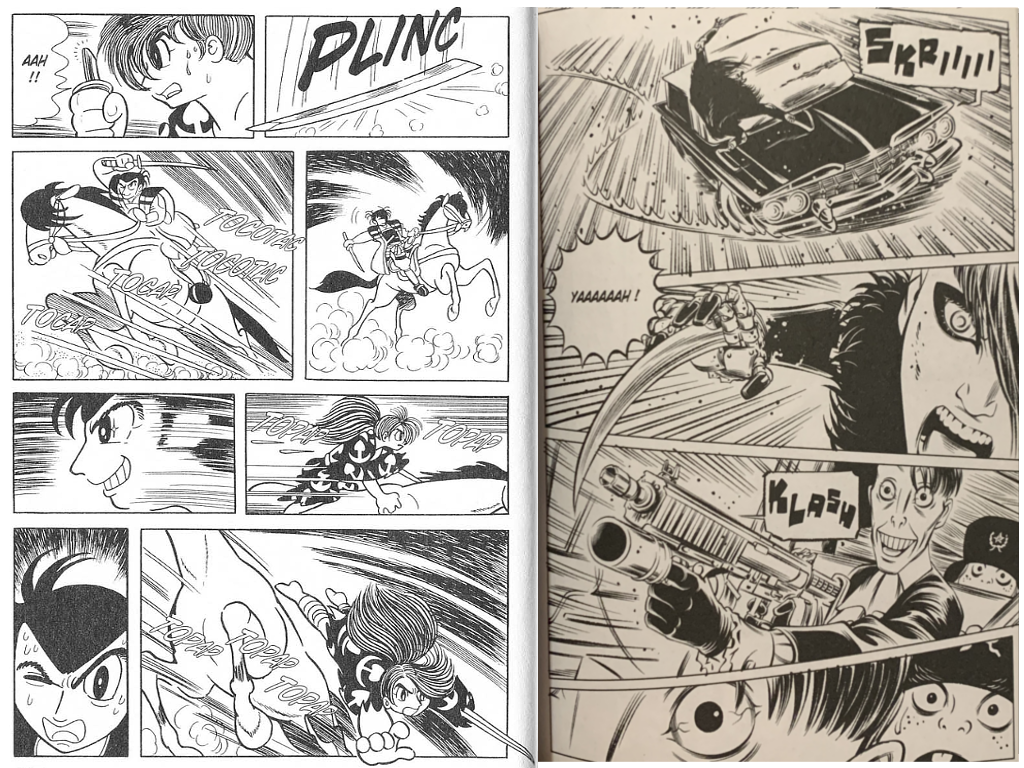

His most well-known manga is Bambi and Her Pink Gun started in 1997; it is the story of a pink-haired and pink-gunned killer woman escorting a baby like in Lone Wolf and Cub.

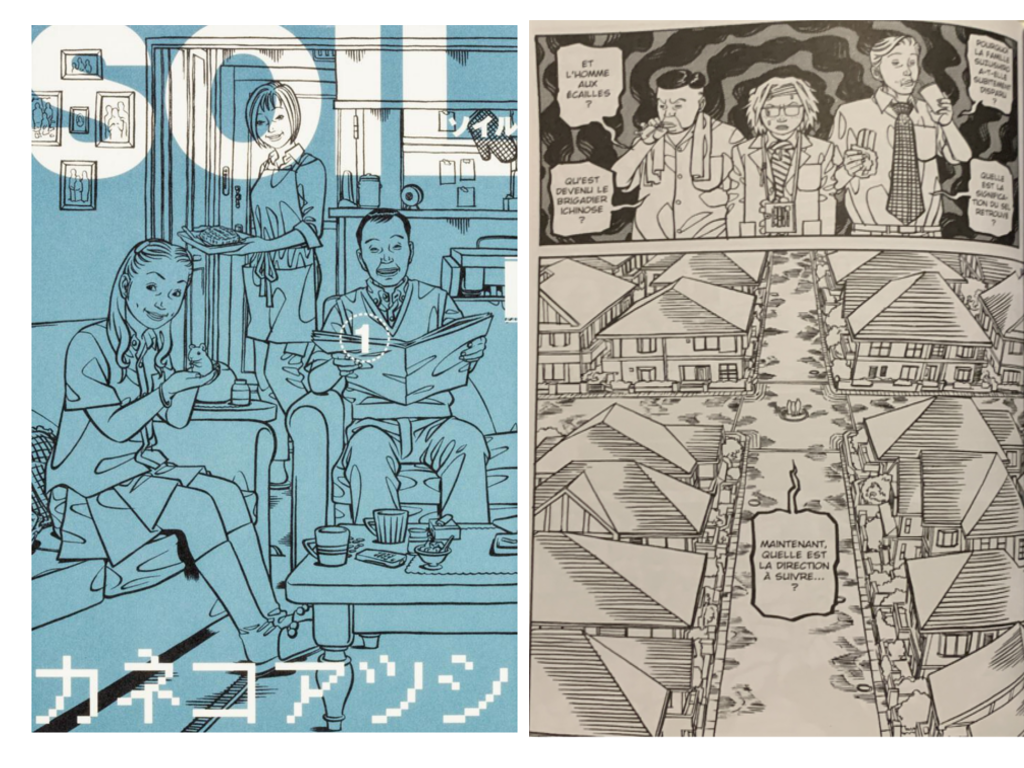

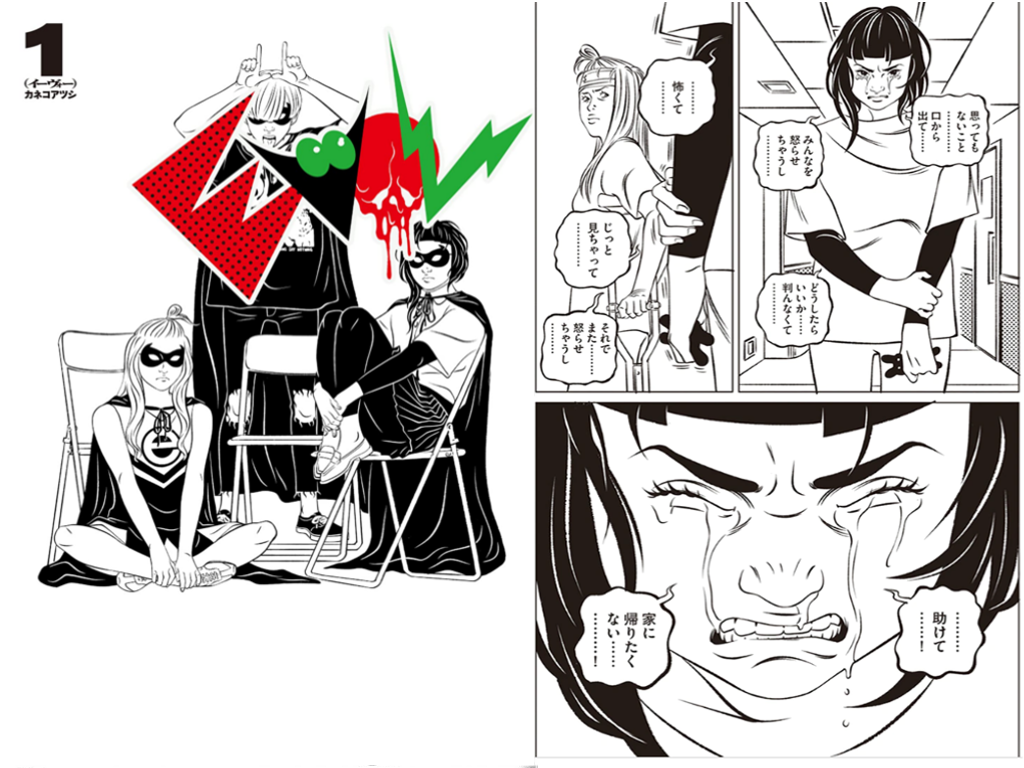

After that, he made a lot of other series, like Soil and Deathco, and his still ongoing one, EVOL, which started in 2020.

Almost none of his mangas are published in English, except for Bambi, but its publication was unfortunately dropped after two volumes.

On the contrary, Atsushi Kaneko is quite famous in France, having almost all of his works published and well-received. He came several times in the past, for example, at the International Comic Festival in Angoulême. He came again in 2023 for the French release of EVOL. I was able to shortly meet with him at a signing session. He is a very dedicated and passionate person, still showing a punk look at 57 years old, who clearly loves to meet with his fans. During his trip, he gave a long conference about his whole career at the Maison de la Culture du Japon à Paris, a building in Paris dedicated to Japanese culture, and the following as a translation of that conference!

Hosted by Frederico Anzalone, interpreter Miyako Slocombe.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

Frederico Anzalone: Hello, everyone. Thank you for coming to this meeting with Atsushi Kaneko. He is an author much loved in France, and I’m really pleased to welcome him.

Today, we rediscover you with your manga EVOL, which is a story about revolting teenagers with a nascent super-powers background. We will talk a lot about this work, but also about the beginning of your career and your other work. But first of all, I would like to ask, since we haven’t seen you in France since 2015, in the present world, which has changed a lot since 2015, not really in a fine way, to be honest, how do you feel recently?

Atsushi Kaneko: That’s right, the world is always changing, and it’s clearly changing in a bad way. It is true that when I came to Paris about five or six years ago, I remember having the feeling that the world would be better, little by little, but I realize it is the exact opposite that’s occurring.

Frederico Anzalone: You develop a lot of these current problems in EVOL, such as racism, homophobia, and governance by violence. I would like to know if EVOL is your message to youths.

Atsushi Kaneko: Instead of a letter or a message, what I want to transmit with EVOL, is my feeling of sympathy towards the young people. To tell them, “You are not alone. You are not the only ones suffering”.

Frederico Anzalone: To introduce EVOL to those who don’t know it yet, it is about three teenagers, a boy and two girls, who attempt to commit suicide at the same moment, but in different places. They fail and wake up in a psychiatric institute with weak superpowers developing within them. In this work, you obviously talk about young people’s mental health, but also a wide range of societal problems, and in matters of change and problems of the world these recent years, there is, of course, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, and I would like to know how you lived it three years ago?

Atsushi Kaneko: Like all of you, I had the feeling that this everyday life that we thought would continue permanently could actually collapse overnight. And I took the habit from there of searching for goodness in a restricted frame. For example, I do running in my neighborhood, and it permits me to discover some charming places I did not know about until now.

Frederico Anzalone: Something interesting about EVOL is that it started in August 2020 in the magazine Comic Beam in Japan, which was a few months only after the height of the pandemic. Do you think that we find a trace of the pandemic in a metaphoric or indirect way in this work because it is not approached directly in it? Did you want to talk about it creatively?

Atsushi Kaneko: In fact, I started thinking about EVOL‘s scenario before COVID, so the pandemic-related elements are not directly integrated into the story, and I would even say that mangaka’s lives did not radically change at all with the pandemic, on the contrary, I think I was able to focus more on my work.

Frederico Anzalone: Did you talk with other authors, for example, about the necessity or not to put the pandemic in your stories take place in the real world? I suppose that a lot of authors wondered if it was necessary to do so or not.

Atsushi Kaneko: Yes, it’s a question every artist had to face, and we all wondered if we admit that there was or wasn’t COVID in our stories, in the setting. And this question was especially important since we didn’t know if the world would go back to how it was before or if we would stay uncertain about the shape the world would take.

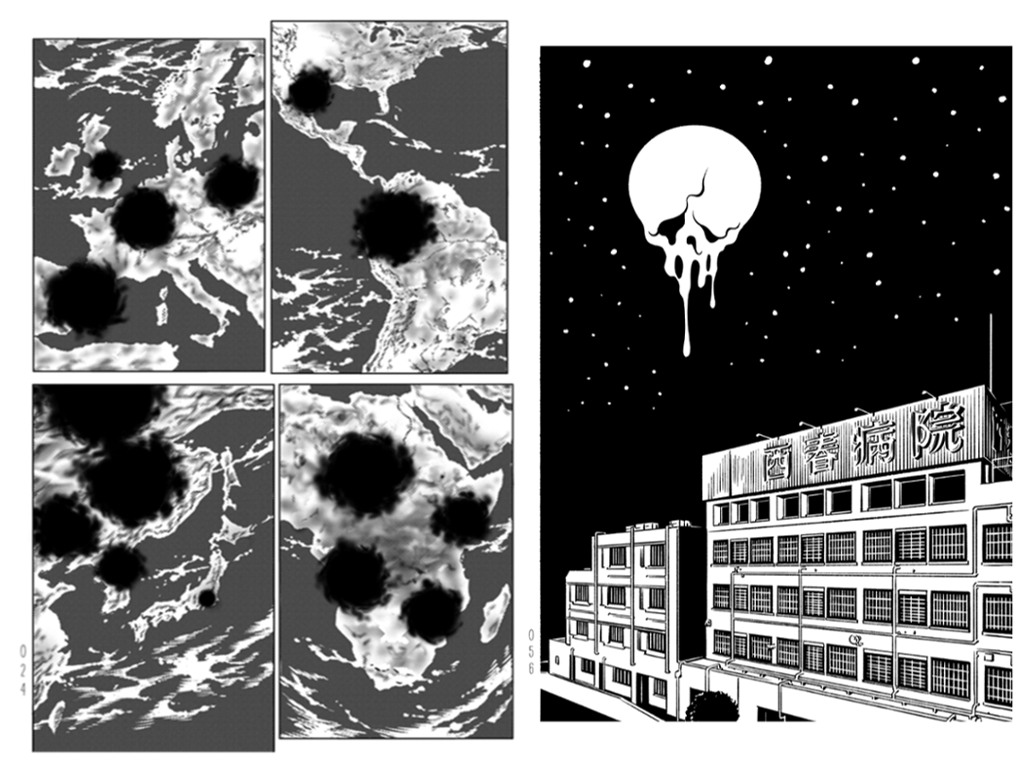

Frederico Anzalone: Personally, when I saw the board on the left, which is the declaration of different powers all around the world, I immediately thought about COVID and the fact that we all were in a huge village, living the same thing at the same time.

Atsushi Kaneko: This image was conceived and thought about before COVID, but it’s true that this idea of evil spreading simultaneously all around the world is related to my feeling about politics, especially with movements in Europe and in Asia, like a dark shadow hovering above the world.

Frederico Anzalone: For information, what we can see on the right is hospital Seishun, which means “youth,” if I’m not mistaken.* It is the psychiatric institute from which the three heroes of EVOL will try to escape. We will talk in detail about EVOL later. First, I suggest we go back into the past, a bit further away. I would like to talk about your childhood and your relationship with manga. Do you remember your first contact with a manga, and what did it provoke within you?

Atsushi Kaneko: In Japan, every kid, without even realizing it, are manga reader, and even I can’t remember the first time I read one, but at that time, there was nothing funnier than manga, and I remember that every weekly release of magazines we liked was the biggest event of the week.

Frederico Anzalone: And what did you read in particular?

Atsushi Kaneko: I was the type not to like the Jump, which everyone was reading, so I tended more towards Shônen Sunday, for example, that I preferred. At this moment, I read manga like Gaki Deka or Macaroni Hôrensô, so more comedy mangas.

Frederico Anzalone: Two mangas that were never released in France, the first one is by Tatsuhiko Yamagami, and the second is by Tsubame Kamogawa. And how do you explain this tropism towards humor? Was it really gag manga in particular that interested you?

Atsushi Kaneko: At that time, I had the feeling they were really avant-gardists. There was a destructive power flowing from these mangas, and I remember I had chills when I read them.

Frederico Anzalone: What do you mean by “destructive”?

Atsushi Kaneko: All of the pre-existing manga theory, manga forms that we knew until then, they were authors having fun destroying them, and from this destruction, something interesting appeared, and that is when I realized that destruction had an interest, and it could give something else.

Frederico Anzalone: And the passion for drawing, where did it come from? Was it already there when you were a child? Were you drawing characters you liked?

Atsushi Kaneko: I have been drawing since I’m a little child. Even before reading or being able to read mangas, I remember that when I couldn’t draw what I wanted, I started to cry. Even now, when I can’t draw what I want, I cry. I think that the character I drew the most is Lupin III, and I remember drawing mangas in this style.

Frederico Anzalone: You were reading the manga or watching the anime of Lupin III?

Atsushi Kaneko: I started with the anime, which was broadcasted when I was in elementary school, and then I read the manga, but I realized it was much more directed to adults, and I remember being a little embarrassed during the reading.

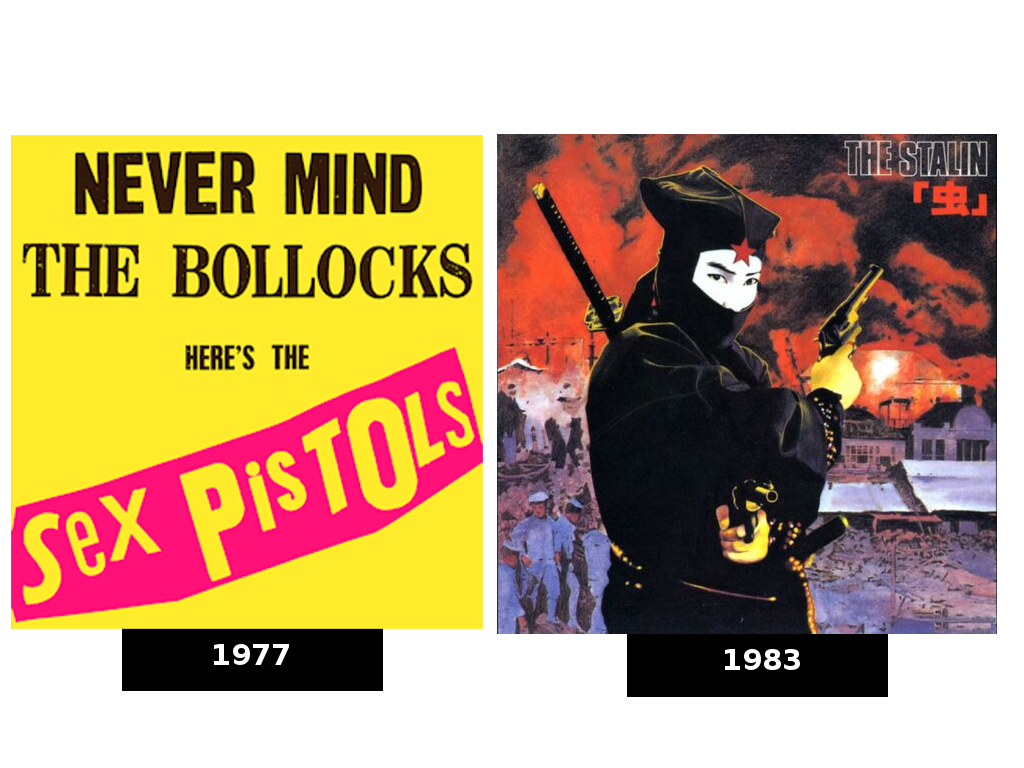

Frederico Anzalone: I suggest we get to adolescence. There is an event that marks you forever. It’s the arrival of Punk Rock. We ramble a lot about the “Punk” qualifier when we talk about your works, but it’s not always the case. All of your works are not punk, but still, in 1977, the Sex Pistols appeared in your life. How did you live that at the time? What did it procure you?

Atsushi Kaneko: First of all, about the reception of Punk in Japan, there were newspaper articles about it. They were considered almost like terrorists. And I was intrigued, so I became interested in it. I started listening to Punk music, and I must say it really saved me. At this time, I was living in a country town, and I was affected by inexplicable anger, especially towards authority, and I realized through this music that young people in England were feeling this anger too, and I realized I wasn’t alone.

Frederico Anzalone: You were around 12 years old, right?

Atsushi Kaneko: Yes, 12-13 years old.

Frederico Anzalone: After getting fond of punk, how did it go for you? Did you start to wear a crest and speak badly to adults?

Atsushi Kaneko: Indeed, my clothes completely changed overnight, and I started having bad behavior. Though it is possible I already had it before.

Frederico Anzalone: About the Japanese version of punk at this time, how was Punk retaken by the Japanese at the beginning? Was there a revolt against authority like in England? For example, the Sex Pistols were angry towards the Queen of England. Did it exist in Japan?

Atsushi Kaneko: When I think of it now, I realize that the most receptive people to Punk in Japan were, on the one hand, intellectuals, and on the other, the thugs and bôsôzoku, Japan’s biker gangs. There were two different forms of punk.

Frederico Anzalone: What we see here is the cover of the album called Mushi by the band The Stalin. It is another form of punk rock because it arrived 6 or 7 years after the original English punk. It seems to me that this is a very dear cover to you, can you tell us something about it?

Atsushi Kaneko: The Stalin are really representative of the “intellectual” category of Japanese punks. I had the feeling that, for the first time, there was a Japanese form of punk. There was this literary side of expression appearing. This cover was drawn by Mangaka Suehiro Maruo, and it’s through it that I discovered his works. I think this discovery was the first step toward my mangaka career.

Frederico Anzalone: What did you feel when you discovered Maruo’s mangas?

Atsushi Kaneko: It is the same thing I felt when I discovered The Stalin’s music, which has a very literary aspect and typical Japanese punk elements. Plus, I found the stories really interesting and not lacking in humor. To put it simply, I thought it was very classy.

Frederico Anzalone: Can we reattach this to the “destructive” qualifier you were talking about earlier on? Medium destruction?

Atsushi Kaneko: Yes, it’s true. Besides, Maruo deals a lot with themes we should not talk about in manga. I found interest in his way of developing his stories and the poetic tone of his writing. In his way of telling stories, I felt he was destroying to build something new.

Frederico Anzalone: It’s interesting you are talking about poetry and literature because we tend to put you in boxes such as belonging to the movements of rock and cinema, which we’ll talk about later. But are there any other art forms or influences that are important to you, like literature, for example? And doing so, would you like to re-establish the truth about the real spectrum of your influences?

Atsushi Kaneko: It’s true that The Stalin and Maruo’s works had a deep impact on me when I was in high school, and I discovered a lot of inspiring literary and cinematic references through them.

Frederico Anzalone: Like what?

Atsushi Kaneko: I would mention the director Seijun Suzuki for the cinema, and in literature and poetry, Georges Bataille, who is mentioned also by The Stalin and Maruo.

Frederico Anzalone: So, as you are talking about Seijun Suzuki, a filmmaker, I would like to talk about cinema. After your economics studies, you decided to aim for a cinema career, and I would like to know how it went and how it ended because you’re not doing cinema now, as far as I know.

Atsushi Kaneko: First, concerning my economics studies, I still wonder why I chose that very path. I was a really bored student, so I went to see movies, and from this was born the desire to do a job where I could tell stories, and I naturally thought about cinema. But at the same time, the Japanese cinema industry was a class system, I thought it was really strict and stubborn, and I had the feeling that we couldn’t express ourselves creatively speaking. So I made the choice of engaging in a mangaka career, but the desire for cinema wasn’t leaving me either, and I was asking myself, “Why am I doing manga?” Finally, two years after starting to do mangas, I went to a cinema school. And in this school, we were making auto-produced movies. I was able to touch a little part of the cinema industry, but in fact, creating things altogether, more than the joy it brings; for me, it was mostly a feeling of constraint that was important. I did not feel free enough in those collaboration projects. And I realized again why manga gave me this liberty and why it was such a wonderful medium, and finally, that’s why I returned to it.

Frederico Anzalone: Did you get your economics degree?

Atsushi Kaneko:[laughs] Yes, it was close, but I got it.

Frederico Anzalone: Is it useful?

Atsushi Kaneko: I forgot everything.

Frederico Anzalone: To come back to manga, it is quite unknown, but you drew a lot of things before making Bambi and Her Pink Gun, the work that put a light on you in 1997. There are two works on which I would like to stop. First, the one on the left, called Rock’n Roll igai wa zenbu uso, so, “Besides Rock’n Roll, everything is a lie” I want to know what did this experience bring to you and what was it about?

Atsushi Kaneko: It is indeed the work I debuted with, and to be honest, I would like to forget it. It’s a story about a prostituting boy, who loves Elvis, and so by prostituting, it’s like he’s lying to himself, and by this process, he is really becoming Elvis, and he goes in a worse and worse direction. Sounds pretty lame, doesn’t it?

Frederico Anzalone: Not at all! [laugh] It was not a big success, right?

Atsushi Kaneko: Oh yeah, it ended without anybody knowing this manga’s existence.

Frederico Anzalone: [laughs] And the one on the right is called Mittsu no Onegai, so The Three wishes. Many don’t know it, but you worked on this with a great scenarist called Caribu Marley, which is obviously a pseudonym, and who is the scenarist of the manga Old Boy, which is the starting point for the movie by Park Chan-wook. How did you, as an unknown man, find yourself working with such a big name at this time?

Atsushi Kaneko: It happened through very funny circumstances. In fact, at this time, Caribu Marley wanted to create a music band because he was practicing drums, and he was asking around him if there were other mangakas performing music. I was playing bass, and Caribu and I had the same editorial manager, so it was through him that I was given the offer to start a group with Caribu Marley. We got joined by a third member, playing guitar, and we did repetitions in the studio, and after it, we drank at Caribu’s place. And during those nights, until the morning, he was always lecturing us. At this time, I was debuting, and I think that for him, I was just a brat, but he told me, “One day, when you have gotten better, I will accept to collaborate with you.” So we collaborated on this manga, and I think that it’s because I was not good enough that this project did not work out. However, it was very enriching for me to see how he created scenarios and his way of creating twists in stories. For example, all of a sudden, he integrated a scene in his scenario, not related to the main story, and in the scenario I received, he wrote on the side, “That is what we call setting, did you understand me, little Kaneko?”. [laughs] It was very instructive to me.

Frederico Anzalone: So, let us remind that, until then, you weren’t really successful, but it changed in 1997 with Bambi, which we can see on screen. Bambi is the story of a merciless killer woman escorting a shipment, which is actually a little boy, who will be pursued by a succession of hitmen. Why do you think Bambi worked, even though what you did before didn’t?

Atsushi Kaneko: I think that before Bambi, before acquiring this style, I was in a phase of preparation. And I think this is at the moment when all the elements of this phase of preparation were gathered that Bambi started. Until then, I avoided drawing manga-ish things, while with Bambi, for the first time, I wanted to use and benefit from the manga format to create something, and that might be the reason for the success of this series.

Frederico Anzalone: Bambi is a sort of gathering of all of your personal fetishes of that era, music styles, or cinema. What we see on the right, with the gun pointed at us, is the first board of the manga, which rings like a statement of intent. Can you comment on this first board?

Atsushi Kaneko: I really started this board like that in my head, like a statement of intent. I was in a mindset where I was thinking, “Nobody knows me, nobody reads me, even though I draw all of this, but I, I am here!”. It was like a notice of my presence.

Frederico Anzalone: To be clear, something like, “That’s enough, buy my mangas now!” right? [laughs]

Atsushi Kaneko: Yeah, exactly! [imitates a pointing gun]

Frederico Anzalone: And as for today, which place does Bambi have in your heart?

Atsushi Kaneko: I think that at this time, I was afraid of absolutely nothing. I enjoyed a huge freedom when I was drawing. So, when I look at this drawing today, I think it’s really untidy, and at the same time, I drew everything that passed through my mind. It was also the first time I was being read, and it was a pleasure that there was someone on the other side receiving and reading this manga.

Frederico Anzalone: In 2003, you started Soil, which is like a complete U-Turn, because this time, it’s not really a gathering of your personal fetishes, but it’s more like a point of view on society that you’re exposing. It’s an unusual police investigation in a new town, a kind of suburb created piece by piece to welcome new residents. And this suburb, created on the ruins of an ancient village from the Jômon Period, between -13000 and -400 in Japan, is a place where two freaky investigators will try to solve the case behind the disappearance of the family we can see on the left. I would like to know what made you want to tell this story.

Atsushi Kaneko: The truth is, I had this story in mind before Bambi, but at that time, I didn’t feel able to reach the end of this project. And so, I had the feeling that Japanese society was a very flat thing. Nothing would come out, and if there was something a little bit different, a little extraordinary, we would try to cover it, and that’s what I wanted to talk about through this manga.

Frederico Anzalone: What’s interesting in the city of Soil, that we can see on the right, with those perpendicularly lined up identical houses, is that it is an urbanistic development project, stopped because of the bursting of the Japanese asset price bubble, so there is a huge wasteland around the city. Does this bursting of the bubble influence your writing in the series? Did you want to artistically react to this fact?

Atsushi Kaneko: This city has a model called Maihama, and on one side of the train station, there is this landscape of infinite identical houses, and on the other, it’s Disneyland. I found that interesting.

Frederico Anzalone: The true Disneyland?

Atsushi Kaneko: Yes, the true Disneyland of Tokyo, in Chiba. And concerning the bursting of the bubble, yes, there was a feeling of loss, and in the same way, this Maihama town had a lot of emptied houses, besides it was supposed to be a growing and developing project, but everything was retracting, it hit me.

Frederico Anzalone: What we see on the right, it’s a scene from the Jômon period, a tribal ritual. And so, we said earlier that you gave up on cinema, but not quite, because, in 2005, you directed a segment of the omnibus movie Ranpo Jigoku, adapting Edogawa Ranpo, the novelist. I would like to know, how did you come on this project?

Atsushi Kaneko: Earlier, I told you I went to a cinema school but that I finally chose manga. And in fact, it was a producer who read my mangas that offered me this project, so it’s manga that made me come back to cinema. The producer was a Soil fan, but he didn’t know I went to a cinema school, so originally, he proposed to me that I design an animated movie, but I told him I would prefer to make a live-action movie, and that’s how I integrated the project.

Frederico Anzalone: And what is your personal affinity with Edogawa Ranpo? The author of The Black Lizard and the cases of Kogorô Akechi.

Atsushi Kaneko: When you are a Japanese kid reading books, at a certain point in your life, you will pass by the Ranpo step. Edogawa Ranpo is a pretty well-known author for the strange and creepy side of his works, but I thought there was also a lot of humor in his books, and this is this humoristic aspect that I wanted to bring into my adaptation.

Frederico Anzalone: On the set, it’s interesting to know that you directed Tadanobu Asano, who is a very famous actor in Japan. We can see him on the left, in the center of the cover. How did the collaboration with him go? Did he know your mangas?

Atsushi Kaneko: Asano comes from the punk culture, too, so there was instantly goodwill between us. It was easy to communicate with him. Asano had never read my mangas, but the movie staff had the kindness to provide mangas I drew in the break room, and I remember that Asano read them and said, “Oh, it’s super funny, what you do!”. [laughs]

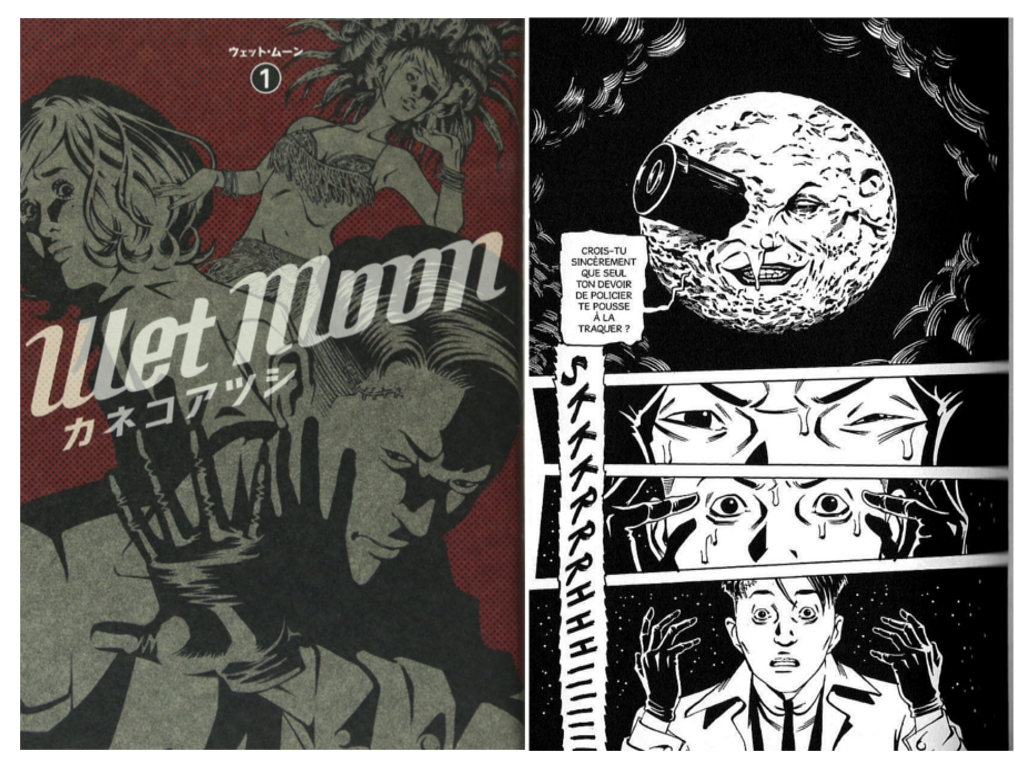

Frederico Anzalone: To stay on the topic of cinema, your next manga is Wet Moon, which is actually the most cinematographic of your work, not only in the form but also because it was a movie you wanted to direct, and it didn’t happen. Wet Moon is the story of a hallucinating detective called Sata, chasing a killer woman in a red coat, about whom he’s obsessed. Why did this movie not make it?

Atsushi Kaneko: Simply because of budget issues. Actually, the movie was going to cost a lot of money. One could think, in the beginning, that a police story would not cost that large amount of money, but the story takes place in the 1960s, and unlike Paris’s streets, Tokyo’s had changed a lot, and building the scenery was going to cost a lot of money.

Frederico Anzalone: With this work, we start to understand what is, for me, the main topic of all of your works, which is the hidden truths. At the same time, hidden truths about the world and of individuals. During a previous interview, you told me that Wet Moon is a work during which you nourished yourself with your emotions right after the triple catastrophe of March 11th, 2011, the earthquake, the tsunami, and the Fukushima nuclear plant, and you said it helped you understand this event, the fact that the peace we live on is built on a scaffolding made of lies that can collapse and reveal the harsh truth. Now, in hindsight, do you think this event has deeply changed your creations and Japanese creations in general?

Atsushi Kaneko: It’s like I told you before about COVID; after March 11th, every mangaka was wondering how to manage the continuation of their stories because it was such a big catastrophe that it even changed the shape of Japan. Was it necessary to tell stories and act like it never happened, or on the contrary, going with the fact that there was this catastrophe that we lived in post-March 11th? By chance, the work I started at that time, Wet Moon, took place in the 1960s, so I needed not to ask myself this question, but I still wanted to link this event to the story I was telling, and that’s why I made a choice to suddenly have this scene which recalls the March 11th catastrophe. In this scene, taking place in the 1960s, there’s a young girl saying that the world is unstable and evoking pictures of September 11th and March 11th. It was a way to say that everything is related to the present world, what is going on today.

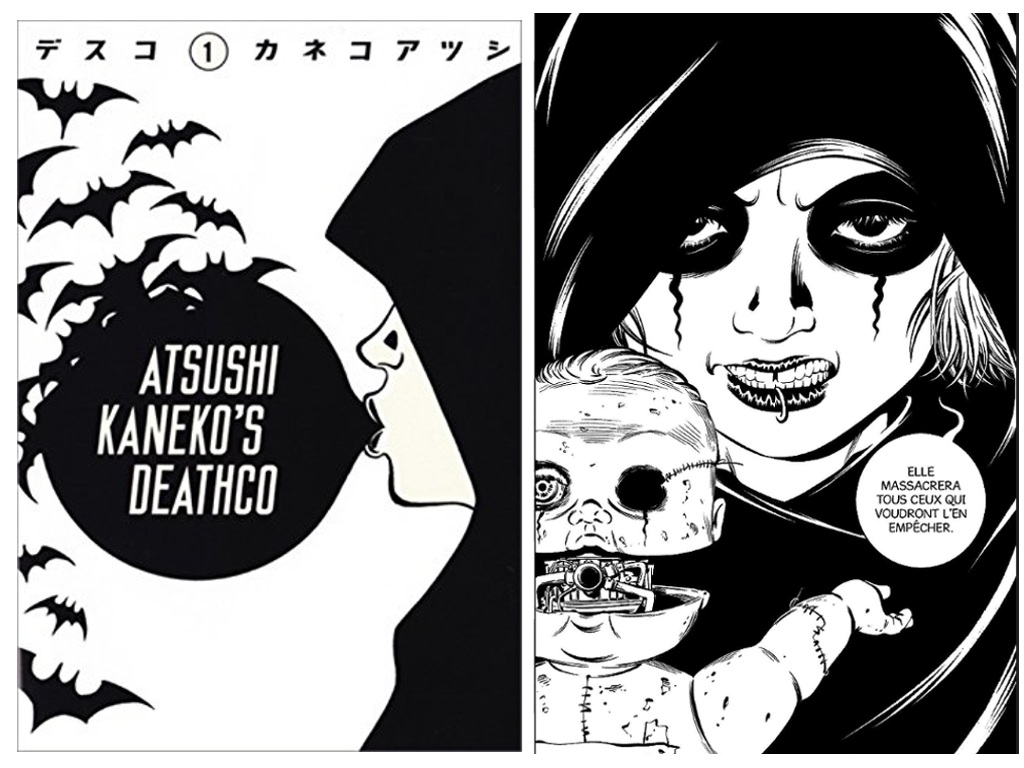

Frederico Anzalone: Your next work, Deathco, is a lot more playful. We find the spirit of Bambi in a more gothic version. Once again, it is a gathering of personal fetishes. It’s the story of a killer woman named Deathko, fighting with modified toys and who hates the whole world. When she’s not killing, she’s caged in a castle, looking like Hammer movies from the 1960s. With what mindset did you approach this series, and what did you want when starting it?

Atsushi Kaneko: Even if I drew a lot of different stories, I was always told about Bambi, people rehashing this story to me, so I said to myself, “I’m gonna kill Bambi.” It’s true that Bambi has a Yin and Yang side, and I thought that the punk and gothic aspect of my passions wasn’t really expressed a lot in my work, so I wanted to show it and integrate it in the tone and the colors of the story.

Frederico Anzalone: There is something kind of unknown about Deathco. You talked earlier about Seijun Suzuki, but in fact, the concept of this guild of killers in Deathco is inspired by Suzuki’s movies Branded to Kill and Pistol Opera. And in Wet Moon, too, you are inspired by 1960s Nikkatsu movies, like Seijun Suzuki’s, who is a very important Japanese director known for his iconoclast police stories and his formal inventions. What are your real feelings toward Seijun Suzuki?

Atsushi Kaneko: The first movie of Suzuki I saw was one he made quite late, Zigeunerweisen, and I remember I really liked the rhythm and the way he developed the story through images and sound. It was a real pleasure to watch it, and it’s through this movie that my interest in Seijun Suzuki was born.

Frederico Anzalone: In Wet Moon, the type of Nikkatsu movies from the 60s, like Suzuki’s, from which you were inspired, what was it, of what particular movies were you inspired or made a reference to?

Atsushi Kaneko: I think you guessed it with this cover. I was really inspired by Suzuki’s Branded to Kill, it’s a really weird movie that I liked a lot, and it inspired me for this manga.

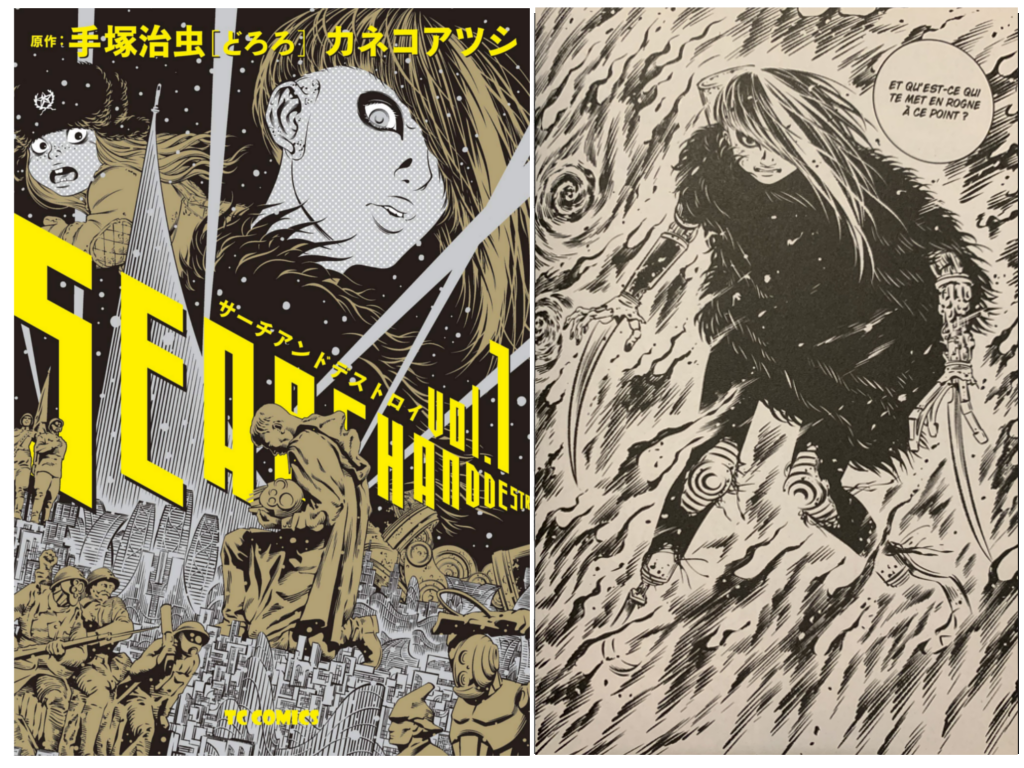

Frederico Anzalone: Yes, it’s truly a crazy and awesome movie. It’s a must-see. Your next project is an adaptation of a manga by Osamu Tezuka, which is Dororo. The point was to participate in a project called Tezucomi, a Japanese magazine in which some artists were invited to remake some of Tezuka’s works. I was wondering if Dororo was your own choice. Did you have the choice to select any of Tezuka’s work, or did they ask you to make Dororo?

Atsushi Kaneko: In the beginning, I wanted to adapt a totally unknown manga from Tezuka, and I told the project manager that a manga like Dororo was too big for me to deal with. And he replied, “Oh no, please choose a manga everyone knows.” This is why in the end, I chose to adapt Dororo. It’s true that thinking of it if I adapted an unknown manga, it would have been the same thing I was already doing until then. And at that time, I was already thinking about a story with a half-machine human with mechanical parts in his body. And making the link with Dororo, I realized it worked perfectly well, so I was sure it was this manga that I should adapt.

Frederico Anzalone: What was the unknown manga you wanted to adapt?

Atsushi Kaneko: I forgot the title. It was a short story.

Frederico Anzalone: What was it about?

Atsushi Kaneko: Now that I think about it, it’s a story that kind of looks like EVOL, with the hero acquiring superpowers by touching a tree, and it’s bringing him into insanity. Ah, I remember the name; it was Euphrate no Ki.

Frederico Anzalone: So on the left, it’s the original work by Tezuka, dating from 1967. It’s a historical story, while Search & Destroy is a cyberpunk story. For the first time, it is an order work. Were you asked for some forced gimmicks, like “make something Kaneko-ish,” or were you free to do what you wanted on this project?

Atsushi Kaneko: There was no particular asking, I was totally free, and I proceeded the same way as with my other works.

Frederico Anzalone: We’re coming to EVOL, the manga you’re currently drawing, and to me, it is kind of the same trajectory you had with Bambi and Soil, which means you purify your graphics, and you come back to tangible topics, more real social problems. So after a very cathartic and furious series that were Deathco and Search & Destroy, what made you return to real and down-to-earth thematics?

Atsushi Kaneko: It is something totally deliberate from me, and I told you earlier that it’s a work I was thinking about before the pandemic, but I already had this feeling that something in this world wasn’t going well, and it concerned Japanese society too. I felt like until now, I dealt with those problems, but in a diagonal approach, but it was not the right time to do this anymore. There’s a sort of emergency, and I had to face those problems of society in a more direct way.

Frederico Anzalone: And, as I said, you’re purifying your graphics. Why this choice to simplify your drawings, compared with the really detailed style there was in Search & Destroy, notably because you switched to a digital tablet since the later half of Deathco?

Atsushi Kaneko: First, I acquired more confidence in my drawing, and I had the feeling that I could make it with a refined stroke. I also felt like having more whites could give more space to the reader’s imagination, and I thought it was really appropriate for the story I wanted to tell.

Frederico Anzalone: What’s funny is that, when we look at Soil, we can see it’s a work where you consciously radicalized the simplification of your stroke, but gradually, with the story going on, the drawings become more complex, there are more details and matters, and it will be evolving like this with Wet Moon, Deathco and Search & Destroy, there’ll be more details, naturally. After three years of EVOL, do you feel this complexification process coming back into you, like a habit naturally returning?

Atsushi Kaneko: Yes, I particularly pay a lot of attention for it not to occur. When the story starts to become bigger in the scenario, I want to add strokes and all, but I’ll erase them right after.

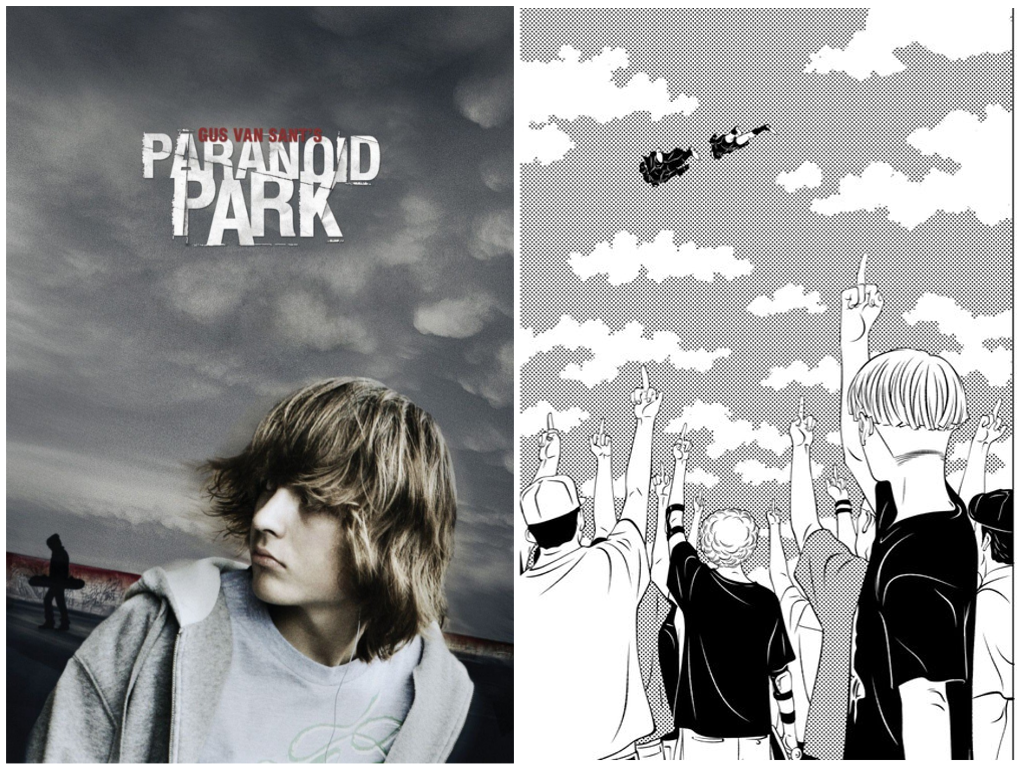

Frederico Anzalone: We were talking about cinematographic references earlier. Are there movies that could have inspired you on EVOL? For example, I thought about Gus Van Sant’s movie Paranoid Park from 2007, which is about teenagers’ feelings, and partly takes place in a skate park, just like in EVOL. Are there movies that could have nourished you?

Atsushi Kaneko: It’s true that Paranoid Park could have been an inspiration because I made the hero Nozomi a skater boy. There’s also a skate park near my place, and I was quite intrigued by this skaters’ community. At first, they look very free, but at the same time, we’re not sure what is being tied between them, and it probably inspired me for the scenario.

Frederico Anzalone: So EVOL, it’s obviously about young people and what these youths are going to make with this world they’re going to inherit. Do you have confidence in the current youth and its ability to face the present crisis and build a great future?

Atsushi Kaneko: For me, be it the present young people, the young that I was, those around me, or the young from 100 years ago, I think they are all the same in some kind of way, they are not changing, but I also feel like no matter the era, adults will not have confidence in youths. But personally, I also have the impression that compared with my youth, currently young people are way more aware of problems around them, and they really have an opinion about it.

Frederico Anzalone: The difference is also that today there is an emergency. Ecological problems, among other things, there is an emergency to react. Are you worried about the young people and their future?

Atsushi Kaneko: Yes, I said earlier that originally, I thought the world was going better, and it’s the exact opposite that has happened. But I still have the impression that we’re moving by cycles, and nonetheless, progress is being made.

Frederico Anzalone: What we see on the right are the young at the skatepark, showing their middle fingers to the superheroes. And on the left, it’s heroes Lightning Volt and Thundergirl because, in this world, there are young people getting their powers by failing their suicide attempts, and people getting their powers hereditarily, having a kind of privilege over the others, and are manipulated by authority. When we see those superheroes, even if they are insane, with their SM costumes, we obviously think of American superheroes, and we can wonder if you read comics that deconstruct superhero figures, like Watchmen, The Boys, or maybe you saw the movies and series.

Atsushi Kaneko: Yes, I like Watchmen a lot, and I already loved Batman before, especially in the way of interpreting the figure, how the Batman story evolved, through the interpretation of the character, and the way justice is considered a mental illness. Those are things I liked to see and read.

Frederico Anzalone: What’s interesting with those characters, the three heroes we can see, is that their powers come from a failed suicide, and for a few seconds, they were clinically dead. Did you do research about imminent death experiences?

Atsushi Kaneko: No, I didn’t do particular research on the subject of imminent death experiences, but I’m aware that when you experience this kind of thing when you are young, you’re brain dead or temporarily dead, and you wake up, nothing is like before. But all those scientific facts, I ignored them to progress into my story… I should not have said that. [laughs]

Frederico Anzalone: When we watch the timeline, Bambi and Deathco were improvised works centering on a strong character. Soil and Wet Moon were written in advance, conscientiously. Search & Destroy, and EVOL are in which category?

Atsushi Kaneko: EVOL is really in-between concerning my two ways of doing, on the one hand, the complete improvisation, and on the other, the scenario written in advance. So I already know how the story ends, but there are some points in the story that are not decided yet, not built yet, and I would like to let heroes link these points together according to their desires and feelings.

Frederico Anzalone: How many volumes could it last?

Atsushi Kaneko: It’s something that always seems really important to French readers. In Japan, it’s already up to Volume 5, and I think I’ll go until Volume 8 approximately.

Frederico Anzalone: To quickly come back to Search & Destroy, is it in the written-in-advance category?

Atsushi Kaneko: As Search & Destroy was part of the Tezucomi project, the story had to last for 18 chapters, so I wrote everything to be sure it would end exactly within 18 chapters.

Frederico Anzalone: We’ll soon be going on to the live drawing, but I still have a few questions for you. We talked about the current crisis, ecological and all, but there is also a crisis affecting the artistic world, artificial intelligence, with software such as Dall-E, Midjourney, etc… What do you think about this, does the arrival of AI in art domains bother you?

Atsushi Kaneko: No, I don’t feel any worries about this. Besides, I think it would be in vain to worry because now that these softwares exist, it will keep developing. We can’t go back to an AI-less world, so we don’t have any other choice than to live with it. At the time, planes didn’t exist for example; I could have never been here, so we can expect anything we wouldn’t have imagined before then.

Frederico Anzalone: Anyway, I think if we enter “manga drawn by Atsushi Kaneko” in Dall-E or Midjourney, it will result in an awful thing. [laughs] It would never be as great as you.

Atsushi Kaneko: We never know [laughs], but maybe I will let an AI draw the rest of the story.

Frederico Anzalone: Today, what is your assessment of your career?

Atsushi Kaneko: I feel like I have done nothing yet. Everything is just beginning. I even got the feeling I was still waiting for things to actually begin.

Frederico Anzalone: Waiting? What do you mean?

Atsushi Kaneko: I’m waiting to be good enough to continue.

Frederico Anzalone: To draw something you have in mind and you are not able to do yet?

Atsushi Kaneko: Every time I draw a work, I have a lot of regrets afterward. I see a lot of things I couldn’t bring to an end. So, one day, I would like to draw a work where I could have brought everything to an appropriate end. I think you all know Hokusai, who was making prints. He continued to draw until he was 90 years old, and the rumor is that he said if he could live another ten years, he would really be a good painter.

Frederico Anzalone: Last question, if we watch towards the future, is there a promise you want to make to yourself in 10 years?

Atsushi Kaneko: I want to tell him to continue to draw.

[It was supposed to be the live drawing, but someone from the staff said that they needed a little more time for the installation, so there are a few questions from the public.]

Public: I have a question related to cinema. You talked about a lot of references, such as Seijun Suzuki, but there’s a director we didn’t talk about at all, which your works really make me think of, in Nobuhiko Ôbayashi, who deals with the meander of the human soul. Through fiction, he freed himself from a lot of cinema conventions to get as far as possible with what pictures would give him, worked until the end of his life, trying to break the limits of his art, and was working on fantastical appearances to express the discomfort of his main characters. And I would like to know if he was an influence, if you saw his movies, or on the contrary, not at all?

Atsushi Kaneko: In fact, by chance, Nobuhiko Ôbayashi is the father of the wife of a mangaka friend of mine. And this mangaka rubbed shoulders with him until a little time before his death, and he said it was someone enjoying monstrous liberty and, at the same time, was really generous. And I remember that in middle school, I watched a lot of his movies. It was the era he released a lot of popular movies. I especially think about I Are You, You Am Me, or Lonely Heart, and in a way or another, it’s really possible his work had an influence on me.

Public: We often find in your works the strong woman figure, destructive, with a lot of character. Is there a particular person that had an impact on you and brought you to create such a type of character? Or is it just a fantasy? What does it express precisely?

Atsushi Kaneko: There wasn’t really a particular model for the female characters, but if my heroines are strong women, I think it’s because, to me, girls are classier than boys. Also, the fact that, with male characters, I have the tendency to bring them closer to me, so to draw a line, I also made a choice to use female characters.

Public: I wanted to know if there is a mangaka on the current scene that you liked, and I particularly wanted your opinion on Tatsuki Fujimoto, the author of Chainsaw Man.

Atsushi Kaneko: I don’t really read manga, so I can’t answer this question. But, this mangaka friend whose wife is Nobuhiko Ôbayashi’s daughter I was talking about earlier, it’s Takehito Moriizumi, the author of the manga Serie, published in France, and I really find his mangas impressive, and I say to myself that I would be absolutely unable to do what he does.

Public: Your works make me think about the “punk” qualified videogame designer Goichi Suda/Suda51. Are you two friends? Do you know him personally?

Atsushi Kaneko: Sorry, I don’t play video games. I don’t know him at all.

Public: It seems to me that you give particular attention to noise and sounds in your mangas. I don’t know if it’s just an impression, and I wanted to ask if it is the result of a deliberate reflection.

Atsushi Kaneko: It’s true that I love to create a rhythm in my mangas, through the paneling, the quotes, but also the sound, and I told you that in Zigeunerweisen by Seijun Suzuki, it was the rhythm that I found really pleasant, so yes, it’s conscious within me, concerning this. Something that frustrates me a lot when I draw manga is that I can’t listen to music at the same time, so I think that through paneling, quotes, and sound, I compensate, and I compose my own music.

Public: We didn’t evoke Atomic, and I would like to know what’s inside it and how does it fit in your work as a whole?

Atsushi Kaneko: It’s a short stories compilation, and between the first one and the last one, there is a gap of around ten years, and they’re all stories I drew on an experimental basis between my longer manga projects.

Public: Thanks for coming to France. What are the pieces of media that inspired you recently, cinematographic or musical?

Atsushi Kaneko: I would say that I don’t let myself easily be influenced by what I watch nowadays. But to tell you what I enjoyed recently, I would mention the movie Don’t Look Up. And regarding music, what I listen to really depends on the period, but currently, I often listen to electronic music. For example, I really like Giant Swan.

Notes

Comic Beam: A Seinen Magazine published by Enterbrain started in 1995, described as alternative, publishing a wide range of genres of stories. For example, Emma by Kaoru Mori and Ultra Heaven by Keîchi Koike are publications of the Comic Beam.

Gaki Deka: Gag manga by Tatsuhiko Yamagami, published from 1974 until 1980 in the Weekly Shônen Champion, about a prankster kid dressed like a cop. Compiled into 26 volumes, it sold around 30 million volumes.

Macaroni Hôrensô: Gag manga by Tsubame Kamogawa, published in the Weekly Shônen Champion, published from 1977 until 1979, compiled into nine volumes. It is about a student who has strange neighbors.

Tatsuhiko Yamagami: (1947-) Former mangaka, now a novelist, who drew mangas of various genres, such as Hikaru Kaze, a political manga about the collaboration between Japan and the United States. At the beginning of his career, he drew some kashihon manga. He retired from manga to become a novelist in 1990, thinking he had nothing more to tell through manga.

Tsubame Kamogawa: (1957-) Mostly a gag manga author, he found great success with Macaroni Hôrensô, but he created many others. His last work dates back to 1997, even if he said he wanted to make a new one.

Bôsôzoku: (暴走族) It is the Japanese term to qualify Japanese biker gangs, driving dangerously and making as much noise as possible. It was a real social phenomenon in the 1970s and 1980s. Many visual codes of this counter-culture are now well-known thanks to art, such as extravagant haircuts and long coats. Their number really decreased through the years.

The Stalin: Japanese punk band formed in 1980 by Michiro Endo (1950-2019), who was a socialist activist. The Stalin got disbanded in 1985 after lots of members changed. In this short gap of existence, they managed to release a lot of albums and EPs, with the first one called Stalinism.

Suehiro Maruo: (1956-) Very important mangaka, considered the master of the Eroguro current in mangas, mixing erotism with grotesque. His most famous works are Warau Kyûketsuki and Shôjo Tsubaki, which was adapted into an OVA. Before starting to publish mangas, he was drawing for pornographic magazines.

Seijun Suzuki: (1923-2017) Japanese movie director considered one of the most impactful by many people, even by Western directors such as Quentin Tarantino. He was extremely prolific, making more than 40 movies between 1956 and 1967 for the Nikkatsu Corporation. In 1968, he got fired from Nikkatsu and was banished from Japanese studios for ten years. His famous works include Tokyo Drifter, Fighting Elegy, and Branded to Kill. He also co-directed the animated movie Lupin III: Legend of the Gold of Babylon.

Georges Bataille: (1897-1962) He was a French writer, philosopher, and poet. He considered writing as a way to transmit his experiences, such as sexual ones. He lived through all new artistic movements of the beginning of the 20th century. His most famous works are Blue of Noon and Story of the Eye, which are both erotic novels.

Caribu Marley: (1947-2018) He was an important Japanese manga and gekiga scenarist. His real name is unknown, and he used a lot of different pseudonyms, such as Dark Master and Garon Tsuchiya. He collaborated with several authors, such as Akio Tanaka and Jirô Taniguchi. He is the scenarist of the manga Old Boy, under the pseudonym of Garon Tsuchiya.

Edogawa Ranpo: (1894-1965) By his real name Tarô Hirai, he is a very famous Japanese writer. His pseudonym comes from the Japanese pronunciation of Edgar Allan Poe. He wrote some of the most famous police stories in Japanese history, such as the adventures of the detective called Kogorô Akechi, inspired by Sherlock Holmes, who became an icon of police fiction, inspiring a lot of works after it, like Case Closed.

Tadanobu Asano: (1973-) His real last name is Satô. He is a famous Japanese actor and musician. He’s considered a great actor, with subtle facial expressions, but always on the spot. He acted in movies like Love & Pop by Hideaki Anno, Ichi the Killer by Takashi Mîke, and Zatôichi by Takeshi Kitano. He even played in foreign movies. He is also a guitarist, playing in a band called Mach 1.67, formed with the director Sogo Ishii.

Hammer Film Productions: Created in 1934, it is a British movie film production company. It is mostly famous for the series of Gothic and horror movies it produced from the 1950s until the 1970s, including movies featuring icons of horror, such as Frankenstein and Dracula. After 1970, the company would then go through a difficult phase, not producing anything for years.

Nobuhiko Ôbayashi: (1938-2020) He is one of the most famous Japanese movie directors of all time. He is a very important figure in experimental movies, starting his career with House, a movie using unique techniques to provide unique images. He made a lot of movies and became more popular in the 1980s, making movies for young people. He was also an extra-prolific television advertisements director. He died of lung cancer in 2020.

Takehito Moriizumi: (1975-) Mangaka, who started in 2010 with Mori no Marie. He is recognized for his unique art style. He sometimes draws with chopsticks. He is very influenced by Western fiction. His most famous work is Serie, a Sci-Fi story about the relationship between a human and an android. He recently wrote an essay about his relationship with Nobuhiko Ôbayashi, the father of his wife.

Goichi Suda/Suda51: (1968-) He is a famous video game designer who created his own studio called Grasshopper. He is known for the explosive tone of his games, using cel-shading and extravagant designs. He’s often described as a punk. The most famous games that Grasshopper made are Killer7 and the No More Heroes series.

Giant Swan: British electronic music band formed by Robin Stewart and Harry Wright. They released their first EP in 2015. Their popularity is growing, and they are considered a symbol of the British electronic music scene.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Oshi no Ko & (Mis)Communication – Short Interview with Aka Akasaka and Mengo Yokoyari

The Oshi no Ko manga, which recently ended its publication, was created through the association of two successful authors, Aka Akasaka, mangaka of the hit love comedy Kaguya-sama: Love Is War, and Mengo Yokoyari, creator of Scum's Wish. During their visit at the...

Benoît Chieux, a career in French animation [Carrefour du Cinéma d’Animation 2023]

Aside from the world-famous Annecy Festival, many smaller animation-related events take place in France over the years. One of the most interesting ones is the Carrefour du Cinéma d’Animation (Crossroads of Animation Film), held in Paris in late November. In 2023,...

Directing Mushishi and other spiraling stories – Hiroshi Nagahama and Uki Satake [Panels at Japan Expo Orléans 2023]

Last October, director Hiroshi Nagahama (Mushishi, The Reflection) and voice actress Uki Satake (QT in Space Dandy) were invited to Japan Expo Orléans, an event of a much smaller scale than the main event they organized in Paris. I was offered to host two of his...

It was a fun read, got me to read Soil just because I learnt the assets bubble bursting was a part of the plot. Thanks Floast!