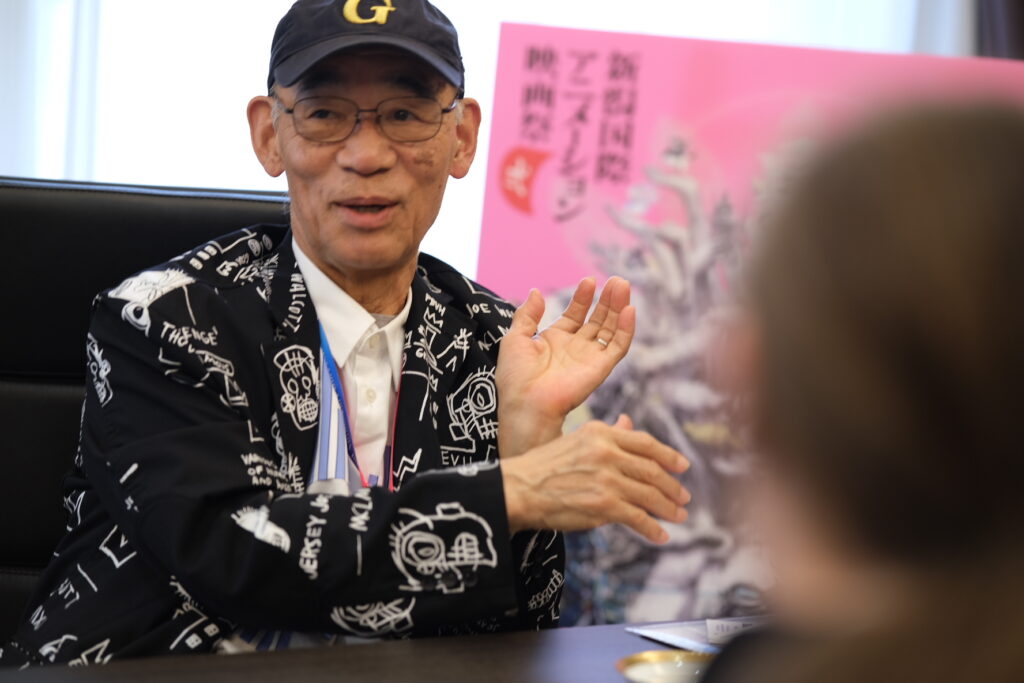

At the last Annecy Animation Festival, we met with a familiar face: Mr. Kôji Takeuchi, whom you’ll see every year at the MIFA to promote his numerous activities. The first time we met him was at the 2017 edition of the festival. He was staying at the hotel in front of our place, and we would share the shuttle bus with him every day. One evening as we were the only people on the bus, he started talking to us, which is when we learned about who he was: a legendary producer in the anime industry. He spent the ride telling us stories about working with Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, as well as anecdotes about the production of Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland.

As Mr. Takeuchi says himself, he is famous for being the only producer who worked with Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata without getting an ulcer.

He began his career at Nippon Animation in the mid-1970s and quickly rose the ranks to become the second president of the studio Telecom Animation. After stepping down from his position at Telecom, he dedicated himself to the training and promotion of new talents. He led and founded many organizations alongside the Japanese government and animation companies. Some initiatives he led are Anime Tamago which is part of the Young Animator Training Project, and the Animation Boot Camp. He also organizes the Tokyo Anime Award Festival, which will be held this year from March 10th to 13th.

We were pleased to sit down with Mr. Takeuchi to discuss his career and asked him to share his anecdotes about working with Yasuo Ôtsuka, Hayao Miyazaki, Isao Takahata, and the other members of their group.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

This article is available in Japanese. 日本語版はこちら

“They were thinking about and making things far more complex than what I had expected”

As a start, we’d like to ask how you came to work in animation. Can you tell us what major you studied in university and how you joined Nippon Animation?

Kôji Takeuchi: In university, I studied something called “organic chemistry”. Do you know what that is? After that, well, various things happened, and I applied for multiple companies, for instance, one producing documentaries, but I always failed. And then, by complete chance, I read about this company called “Nippon Animation” in a newspaper ad. I didn’t know anything about animation, and when I asked “what’s ‘animation’?” to one of my older friends who worked in TV, he didn’t know either. You know, in Japan, we still called it manga. Anyways, my friend told me that if I wanted work, I should take any opportunity, so I took the exam and managed to pass it. As you see, I really hadn’t planned anything.

When you entered Nippon, you quickly entered the group formed by Mr. Takahata, Mr. Miyazaki, Mr. Kondô[1] and Mr. Ôtsuka[2]. Can you tell us more about how everybody gathered there in Nippon?

Kôji Takeuchi: As you know, Takahata and Miyazaki had already been working together for some time. I was just assigned to work with them by complete chance. But when that happened, I found it fascinating because they were thinking about and making things far more complex than I had expected.

As for Ôtsuka and Kondô, Ôtsuka joined Nippon for Future Boy Conan[3] during my third year at the studio. At the time, Kondô was still doing the animation from another company. And then, the next year, there was Anne of Green Gables[4], and Kondô joined Nippon to work with Takahata. I had spent a few years at the company already, and I had the opportunity to follow Kondô’s work quite closely during my 4th year there.

On both Conan and Anne, the directors were in complete control of the production, right? As a production assistant, how did you feel about it? Was it hard to follow up with the directors’ demands?

Kôji Takeuchi: You mean, was Takahata difficult to work with?

More about your time as a production assistant and if you had any particularly difficult experiences.

Kôji Takeuchi: You know, being a production assistant means having to manage time, people, and money, and since, in most cases, nothing happens on schedule, it’s always hard, whatever the production. In terms of difficulty, the hardest must have been Marco[5]… Wait, no, sorry, I meant that regardless of the difficulty, the first production I worked on was Marco, then Rascal[6], then Conan, then Anne. The schedule went off the rails for all of those, so they were all difficult. On Anne, the biggest problem wasn’t really Takahata’s perfectionism; it was rather that the staff we were relying on quit. You see, Miyazaki led the movement and was followed by more people, I don’t know how many, who were all extremely capable, and as a result, things became worse than I could have expected.

“That’s how Ôtsuka did things”

After all this, Takahata went to TMS to direct the Chie the Brat [7] movie, on which you’re credited as Production Desk. Were you and Takahata invited by Ôtsuka?

Kôji Takeuchi: Chie the Brat is a movie about this little girl called Chie and her no-good father, Tetsu. Ôtsuka was the animation director. Ôtsuka preferred working on Tetsu, and there was Yôichi Kotabe[8], who worked on Chie, so they split the work that way. While Ôtsuka did the animation direction, he helped out a lot with other things as well so that everything could go smoothly.

You see, when I arrived on the project, the animation team had already been gathered, but the storyboard wasn’t even complete yet. Something had to be done, so I took Takahata, Ôtsuka, and the assistant director Mikamoto and locked them up all together in an inn somewhere deep in the mountains. I told the people of the inn, “don’t let them leave!”. The closest train station was 30 minutes away by car. I sent the three of them there with paper, pencils, and all the equipment they needed, and I told the inn’s staff to just bring the meals in and out and not touch anything else. I left them there for something like 10 days or 2 weeks.

When they worked, Ôtsuka would make proposals, but Takahata was a perfectionist, so he’d never approve of something that wasn’t on the level he wanted. It’s not that Ôtsuka was bad, but as time went by, he started submitting more things that Takahata would certainly refuse. At some point, Takahata told him it was no good, and Ôtsuka answered, “it has to be that way and not otherwise.” That’s how Ôtsuka did things.

Also, about Chie, it went off-schedule, you see. This happened later, but at some point in the story, there’s a moment when Chie, her mother, and Tetsu all feel like they could make a good family, and then there’s the scene when they all go home from the amusement park. Takahata was extremely concerned about this and would not complete the storyboard for that specific moment. So here’s what happened. The movie was meant to come out for the New Year, but the New Year passed, and still no storyboard. That couldn’t go on, so the senior producers, not me, took Takahata to Tôhô, the distributor, to apologize. Takahata had to promise to do it by March. And, of course, they called me in as well and told me to get it done by March by any means possible. I was glad to be able to somehow. (laughs)

Ôtsuka worked a lot as well, and so did Kotabe. About Kotabe, at that time, he got into archery, so he would train before work and always arrive late. I told him it wasn’t the right moment to be so easygoing, and we were on pretty bad terms after that.

You didn’t have it easy all the time. (laughs) At Annecy right now, there are screenings of Little Nemo[9]. Can you tell us more about your and Ôtsuka’s involvement with the project?

Kôji Takeuchi: Hmm, let’s see… In 1982, a group of 10 people, including Miyazaki, Takahata, and Ôtsuka, went to the US to study American animation. So at that point, of course, Nemo was already on the tracks. Then, when did we complete it? In 1989 I think… But didn’t it come out in 1991? [editor’s note: Little Nemo was released in 1989 in Japan] Anyways, it was finished sometime between 1989 and 1990. During all that time, the staff composition changed a lot. Ôtsuka has already written about this, but the person originally in charge of the scenario was Ray Bradbury, a famous American novelist. Ôtsuka said he wasn’t fit to be the director, but all the people who got the position quit: first Takahata, then Miyazaki, who took away multiple people with him, and then Kondô. At some point, Ôtsuka did have to take up direction since there was nobody else to do it. But then there was Mr. Fujioka[10], the boss, who had very strong feelings about all this and didn’t really let the directors do things as they wanted. So, in the end, even Ôtsuka was fed up and dropped it. Finally, as a last resort, Masami Hata[11] and William Hurtz[12]

co-directed it together. When he was still there, Ôtsuka helped with the animation uncredited, but in the final film, there’s nothing of his work left. I followed it from the beginning until the very end.

At the same time, Telecom participated in Akira. Was there any overlap between the two productions?

Kôji Takeuchi: As I just told you, I was on Nemo between 1982 and 1989, but the production was all fits and starts. It was during one of these stops that discussions of adapting Akira began. Back then, Telecom had acquired a reputation for having gathered a lot of talented people, you see. That’s why Mr. Otomo asked us if we wouldn’t do it, and we agreed. At first, I was a producer on Akira, so I followed the writing of the scenario. At that stage, Otomo hadn’t completed the manga yet, so he had quite a hard time deciding how to end the film. We were still only 4 or 5 people on the staff, and we all went to a hot spring resort in Hakonep; I don’t remember when. That’s where we worked out the plot. But Otomo didn’t know what to do about the ending, so he asked for some more time to think, which we gave him, and then later, the scenario was completed.

That’s when we started organizing the team, such as the color designers and so on. But, you see, we also had Nemo going on: Fujioka requested that we make another pilot, and we had no choice but to comply. That pilot wasn’t the one that’s famous now, by Kondô and Tomonaga[13], but another one by Dezaki[14] and Sugino[15], and because of that, most of Telecom’s staff was taken away from Akira. I don’t think that made Otomo very happy (laughs). We’re still on good terms anyways, but I don’t blame him for having been angry about it.

Talking about movies and endings, is it true that it’s thanks to you that Princess Mononoke was made partly digitally? Can you tell us more about this?

Kôji Takeuchi: Aah, I see you’re well-informed! The first thing is that at the time of Mononoke, there were new attempts to integrate CG and computers. The other is that it happened when Telecom started to use digital coloring. Mononoke was still partly painted on cels, though. But the production was delayed: the in-betweens were late, they still had to be colored, and Miya-san came to me for advice, asking what they should do. And I suggested that, if it were me, I’d use computers to do the coloring. That’s what I told him. But at the time, there was still a problem with aliasing. Because of that, Miya-san said it wouldn’t work, but I said that if we increased the resolution, there would be no issue. At the time, the cel painting chief was Ms. Yasuda[16], who liked things to be done the right way, so Miya-san left me to explain it to her. Here’s what I told her: “Cels have these problems. Machines have these problems. Which one will you take? In your place, I think I’d prefer for the movie to be in color.” A few days after that, really just a few, Ghibli bought the same computers that the CG department of Warner Bros. used. Warner only had one unit, but they bought a good dozen of those.

At Telecom, we were still using normal Macintosh computers, so it was really surprising to see them suddenly buying such expensive ones. (laughs) And that’s why, thanks to CG, the colors on Mononokewere done right. We had a good partnership with a cel painting company, and when we both upgraded our computers, we also helped them out.

“Ôtsuka was one of a kind”

Let’s go back to Telecom. Of course, the major figure in the studio was Yasuo Ôtsuka. Can you tell us more about him and your relationship?

Kôji Takeuchi: Well, if I had to say, Ôtsuka was someone multifaceted. Of course, his ability as an animator was unparalleled. Even as an animation director, he didn’t follow the usual way of doing things. It’s something that wouldn’t be possible in France or in the US. The usual method in Japan is to refine other people’s drawings by adding modifications so that sometimes the final result is totally different from the original artist’s. This kind of thing is absolutely forbidden in the US. But that’s how things are done in Japan. When their drawings are modified, animators will understand if the animation director improves their work, but when it’s not the case, they’ll get angry because they don’t understand why they had to be corrected. When Ôtsuka did corrections, this kind of thing never happened. That’s because he was one of a kind. His corrections were efficient and used the original drawings as a springboard to reach the highest possible level. That’s how he was.

As for how he was outside of work, he looked like an extraordinarily carefree old guy. At least, not the very industrious kind. When he arrived at the studio, first he’d open a bottle of Coke, then walk around here and there to talk with the people from the cel painting or art department, and even when he had sat, he’d rise again and go off somewhere. When he came back from lunch, he’d stop at a gas station to play table games. It was only after that he came back to work. Well, that’s how he was.

And there’s more! From the outside, he felt very carefree. But he had an incredible level of concentration, so he got the job done as needed. Then, he had various interests, like Jeeps, playing pranks on people, or rather making them have fun. Miyazaki was like that as well. One day, Miyazaki bought an off-road bike, a 125cc one. Back then, I went to work riding a 50cc one, and I told him to stop driving it because it was dangerous: he doesn’t have very good reflexes, you see. Later, he arrived wrapped up in bandages saying, “Takeuchi, help me!” But just by looking at it, you could tell it was fake. The bandages were new and weren’t wrapped properly, so they were all loose. I removed them and told him to stop kidding. He only did that to scare me; he never got into any accident!

Sometime later, we all went to the sea together. At the time, Ôtsuka had a 50cc bike as well, but since we went as a group, he came by car. But when he arrived, he was covered with bandages. Since it was Ôtsuka, I told him he should stop making the same old jokes as Miyazaki, but he said that it wasn’t fake and that he had really gotten into an accident with a truck, and his bike was rolled over. It was all true. But anyways, he liked doing pranks.

For some time, Ôtsuka was in charge of training Telecom’s new recruits. Can you tell us more about the training program?

Kôji Takeuchi: Let’s see… As you know, I was the president. From my perspective and for the company, when new people come in, the best is to make them able to do in-betweens in as short a time as possible. Basically, Telecom’s training program was organized with that purpose in mind, and Ôtsuka also followed it. The training period was three months, so in the first month, he would teach the basic principles of movement and such, and then how to make drawings that would make suitable in-betweens – because in Japan, we can be quite annoying about line drawing and tracing. Lines have to be drawn with perfect consistency. Since it’s so important, they’d spend two months training for that. Then, we’d let the recruits do in-betweens.

One year, Ôtsuka gave a lecture at Telecom similar to the one that he once gave at the Gobelins, and rather than drawing key animation, he explained things from the beginning, saying that the larger the movement, the easier it is to convince the audience. Actually, I was against this teaching at the time. Because in Japan, when someone enters a studio, they never do key animation at the beginning. First, they join as an in-betweener. If you can’t draw clean lines as an in-betweener, you can’t work in animation. But Ôtsuka preferred to teach the basic principles of movement, which left less time for in-between training, and because of that, it took more time for the new staff to acquire the necessary skills.

During my last years at Telecom, I organized a boot camp to develop human resources, and at first, I was thinking of something that could efficiently produce good in-betweeners. But I realized that it was useless if you couldn’t have people who can consider the essence of animation and that people who don’t consider key animation from the start can’t do animation and won’t develop properly afterward. That’s when I understood that Ôtsuka’s method was the right one. That’s what the boot camp is like now: for the students to understand what they want to do and for the lecturers to support them, show them what skills they lack, and teach them. That’s how we do things.

“To go independent, you need a certain level of ability”

Is it still going on now, even with the pandemic?

Kôji Takeuchi: Last fall, we did a face-to-face session with everybody in Niigata. We taught both 2D and 3D animation. It had been a while for us, so we were happy to be back physically, and the students there were as well, so we’re going to do another session this year with the schools from there.

Who are the lecturers for this year’s session?

Kôji Takeuchi: It’s not decided yet. Last year, we had Takeshi Inamura[17], Takayuki Gotô[18], three people from Production IG’s studio in Niigata, and Ryo-Timo[19]. I forgot the names of the people in charge of 3D. (laughs)

Ms. Kuroda: Wasn’t it Mr.Komori[20]?

Kôji Takeuchi: Yes that’s it! And there was also Nobuo Tomisawa[21].

There are other training programs like Anime Tamago, Anime Mirai or Anime no Tane[22]. Have you also worked with them?

Kôji Takeuchi: These are different: they are national projects made to create a better environment for professional animators. Anime Tamago and Anime Mirai are similar; they were about making a single 20-30 minutes short within a single company. These productions are made with a special focus on key animators. In order to develop their skills, we thought of that curriculum, but as we were building it up, we thought it would be good to combine actual on-site experience and assignments like the ones there are in school. That went on for 6 to 8 months in order to produce people whose animation skills are a level higher than the norm.

To answer your second question, at the time of Anime Mirai, my studio applied to make a production with the program, and after that, I was involved in Anime Tamago as a sort of director in charge of developing the curriculum, establishing it, thinking what would be good to develop the skills of the people from the companies that apply, things like that. I have no connection with Anime no Tane, so I don’t know about them, but I think it’s about making shorter works and training people along the way.

Sunao Katabuchi[23] was a lecturer in your Animation Boot Camp. Are you going to provide any help on his next film?

Kôji Takeuchi: What is it about already? The Genji Monogatari? Or the Heike Monogatari? I don’t remember.

Ms. Kuroda: I think it’s the Genji? [editor’s note: Sunao Katabuchi’s next movie will be about poet Sei Shonagon and life at the Heian court].

Kôji Takeuchi: I didn’t know that Katabuchi was going to make a movie about that, so I have no comment to make.

We’ve talked about animators all this time, but we’d like to discuss producers as well. Do you think there are any interesting young producers today?

Kôji Takeuchi: Any interesting young producers? Sorry, I really don’t know about that. (laughs) You know, I haven’t been in direct contact with the industry for 10 years now. In Japan today, there are a lot of people creating companies and making them independent. I think that’s admirable. A lot of good people like this have been coming out of IG: first, there was studio WIT, then now it’s h+, I believe? Mr. Honda’s[24] company.

Do you mean +h?

Kôji Takeuchi: Ah, is that the name? Places like that have a strong spirit of independence. Then there are the people who left Ghibli, such as Mr. Nishimura[25]. To go independent like that, I think you need a certain level of ability. I know them personally, but I don’t know how they manage their companies or productions in detail. Still, I think they’re good.

I see. Thank you a lot for today. It was fascinating.

Interview by Dimitri Seraki, Ludovic Joyet and Matteo Watzky.

Translation by Matteo Watzky and Comrade Karin.

Notes by Matteo Watzky

All our thanks go to Mr. Takeuchi and Ms. Kuroda for their availability.

Notes

[1] Yoshifumi Kondô (1950-1998). A student of Yasuo Ôtsuka from studio A Production/Shin-Ei animation, he began to work with Hayao Miyazaki on Future Boy Conan and Isao Takahata on Anne of Green Gables, on which he was character designer and animation director. Between his arrival in studio Ghibli in 1988 and his early death in 1998, he was the third major creative in the studio and the right hand of his two seniors.

[2] Yasuo Ôtsuka (1931-2021). The most important animator in the history of Japanese animation, who trained generations of artists from his time in Tôei Animation in the late 1950’s to his death in 2021. One of the inventors of effects and mecha animation in Japan, he was Hayao Miyazaki’s mentor and close colleague.

[3] Future Boy Conan. 1978 TV series, Nippon Animation, dir. Hayao Miyazaki. Miyazaki’s first and last full TV series, with character designs by Yasuo Ôtsuka and animation by multiple future members of Studio Ghibli. It is generally considered to be one of the best TV anime series of its decade. It was also a test of endurance for Miyazaki, who initially tried to drive the show entirely by himself, causing multiple delays in the production schedule.

[4] Anne of Green Gables. 1979 TV series, Nippon Animation, dir. Isao Takahata. The last of Takahata’s three shows for the World Masterpiece Theater series, made with the team from Conan. It follows orphan Anne Shirley from 10 to 17 as she is adopted into the Cuthbert family in Prince Edward Island, Canada. Like Conan, it was an extremely difficult production where Takahata’s extremely high standard had a toll on the schedule and staff’s well-being.

[5] From the Apennines to the Andes. 1976 TV series, Nippon Animation, dir. Isao Takahata. Takahata’s second World Masterpiece Theater show, it follows young Marco as he travels alone from 19th-century Italy to Argentina to find his mother. The series is famous for its sociological dimension and the influence of Italian neo-realism and has been highly influential among animators who emerged in the second half of the 1980’s.

[6] Rascal the Raccoon. 1977 TV series, Nippon Animation, dir. Masaharu Endô, Hiroshi Saitô, Shigeo Koshi. This World Masterpiece Theater entry centers on the childhood of Starling North and his baby racoon Rascal in the early-20th century United States. Largely forgotten overseas, the series’ titular mascot had a huge impact in Japan and triggered a raccoon boom in the late 1970’s.

[7] Chie the Brat. 1981 movie, Tokyo Movie Shinsha, dir. Isao Takahata. Takahata’s second feature-length work retraces the daily adventures of young girl Chie, her no-good father Tetsu and her quiet mother in a popular neighborhood of Osaka. The staff was mostly made up of Conan and Anne’s teams, including character designer Yasuo Ôtsuka.

[8] Yôichi Kotabe (1936-). Animator and character designer, the third member of a trio formed with Isao Takahata and Hayao Miyazaki in Tôei Animation, A Production and Nippon Animation from the mid-1960’s to the mid-1970’s. He left the animation industry in 1985 after being scouted by Nintendo, for which he provided multiple illustrations and designs, especially on Super Mario Bros.

[9] Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland. 1989 movie, Tokyo Movie Shinsha, dir. Masami Hata & William Hurtz. An adaptation of Winsor McCay’s comic of the same name, this Japan-US coproduction figures among the most cursed cinematic project of all time: started in the mid-1970’s, the movie was completed more than a decade later, after some of the greatest legends of animation and cinema in both Japan and the US worked on it and then left.

[10] Yutaka Fujioka (1927-1996). Producer, creator and CEO of Tokyo Movie/Tokyo Movie Shinsha between 1964 and 1991. A visionary producer, he made TMS one of the most successful animation studios in Japan and pioneered many co-productions with the US or Europe. Obsessed with his passion project Nemo, he took responsibility for its failure and had to quit TMS in 1991.

[11] William Hurtz (1919-2000). American animator and director. He is famous for his work in Disney Animation in the 1940’s and then United Productions of America in the 1950’s. He worked on Nemo thanks to a recommendation by Disney animators Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston.

[12] Masami Hata (1946-). Director famous for his association with Sanrio’s animation department in the late-1970’s and early 1980’s and lavish productions such as The Legend of Sirius or the animated musical Yôsei Florence.

[13] Kazuhide Tomonaga (1952-). Animator famous for his contributions to mecha animation in the 1970’s and his role as one of studio Telecom’s most important artists. He notably collaborated with Hayao Miyazaki on Future Boy Conan, Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro and Sherlock Hound and was chief animation director on Nemo.

[14] Osamu Dezaki (1943-2011). One of the most important and influential directors in anime history, famous for his expressionist, emotional and extremely stylized direction. One of the founding members of studio Madhouse, which he left in 1980, he collaborated with TMS throughout most of the 1970’s and 1980’s.

[15] Akio Sugino (1944 – ). One of the most important character designers in Japan, he was one of the founding members of studio Madhouse and is well-known for his collaborations with director Osamu Dezaki. Their most famous works together include Ashita no Joe, Aim for the Ace, Nobody’s Boy Remi, Space Adventure Cobra, Dear Brother, Black Jack… As of 2019, Sugino was still active as an animator.

[16] Michiyo Yasuda (1939-2016). Chief of Studio Ghibli’s ink and paint division, she was a collaborator of Isao Takahata and Miyazaki since the late 1960’s in Tôei Animation. Notable works as color designer include Anne of Green Gables, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Angel’s Egg and most Ghibli movies between 1985 and 2013.

[17] Takeshi Inamura (1969-). Animator, former member of Studio Ghibli, now a frequent collaborator of directors Makoto Shinkai and Mamoru Hosoda.

[18] Takayuki Gotô (1960-). Animator and character designer, he is the co-creator and former co-director of studio Production IG.

[19] Ryo-Timo (1979-). Animator and character designer, considered to be one of the central figures of the “web-generation” movement of the mid-2000’s. His most famous works are the Tetsuwan Birdy: Decode and Yozakura Quartet series.

[20] Yoshihiro Komori (??). CG animator and director, who notably directed the Gamba to Nakama-tachi movie in 2016.

[21] Nobuo Tomisawa (1951-). Animator from Studio Telecom, still active on the Lupin series. He often collaborated with Takahata and Miyazaki between the late 1970’s and early 1980’s.

[22] Anime Mirai, Anime Tamago, Anime no Tane. The successive names of an animators’ training program launched by the Association of Japanese Animators (and later the Association of Japanese Animations) and funded by the Japanese government Agency for Cultural Affairs.

[23] Sunao Katabuchi (1960-). Director who worked in Nippon Animation, Telecom, Studio Ghibli and Madhouse, he is now the lead creative in studio Contrail. Famous for his movies Mai Mai Miracle, Arete Hime and In This Corner of the World, he is considered to be Isao Takahata’s disciple and closest follower.

[24] Fuminori Honda (1980-). Producer, former member of Production IG, who created studio +h in 2020 and produced Mitsuo Iso’s series The Orbital Children.

[25] Yoshiaki Nishimura (1977-). Producer, former member of Studio Ghibli. Created studio Ponoc in 2015.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Oshi no Ko & (Mis)Communication – Short Interview with Aka Akasaka and Mengo Yokoyari

The Oshi no Ko manga, which recently ended its publication, was created through the association of two successful authors, Aka Akasaka, mangaka of the hit love comedy Kaguya-sama: Love Is War, and Mengo Yokoyari, creator of Scum's Wish. During their visit at the...

Ideon is the Ego’s death – Yoshiyuki Tomino Interview [Niigata International Animation Film Festival 2024]

Yoshiyuki Tomino is, without any doubt, one of the most famous and important directors in anime history. Not just one of the creators of Gundam, he is an incredibly prolific creator whose work impacted both robot anime and science-fiction in general. It was during...

“Film festivals are about meetings and discoveries” – Interview with Tarô Maki, Niigata International Animation Film Festival General Producer

As the representative director of planning company Genco, Tarô Maki has been a major figure in the Japanese animation industry for decades. This is due in no part to his role as a producer on some of anime’s greatest successes, notably in the theaters, with films...

Trackbacks/Pingbacks