Attack on Titan has been running for over ten years in Bessatsu Shonen Magazine and ended recently, but its success story still seems unreal. Hajime Isayama was a young mangaka with little to no experience who gave birth to one of the most successful stories ever told, both in its original manga version and its anime version. The manga has gathered many passionate fans worldwide, and it is no exaggeration to say it might have become the most important work of the last decade. In fact, for many people, that episode created a habit of watching anime weekly and discovered a lot of other pieces from the medium.

After a very controversial ending two years ago, which is still debated by fans, Hajime Isayama has been very discreet and made very few media appearances. However, his publisher Kodansha have recently brought him to two international events, first in the USA in November 2022 at Anime NYC 2022, and in France, in January for the 50th edition of the prestigious Angoulême International Bande Dessinée Festival.

As manga sales have exploded in recent years and completely overtaken the French comics market, the festival has dedicated much of its space to manga. On that occasion, four mangakas were invited: Akane Torikai, Ryoichi Ikegami, Junji Ito, and of course, Hajime Isayama. Isayama’s fame followed him like a curse during the festival, as he was nowhere to be seen or under police protection, like the most famous rockstars you could think of. He only made an appearance for a panel, for which all the tickets were sold out in a few minutes. Fortunately, we were able to attend it. This article will be our best attempt to share with you not only the information shared by Hajime Isayama about his work but also the overall mood at the time.

Fausto Fasulo, the artistic director for the Asian part of the Angoulême Festival, hosted the panel. He is also the founder of two important publications in France: Mad Movies, a magazine dedicated to cinema, and Atom, a French magazine specialized in manga, for which he has conducted numerous interviews with prestigious artists, making him the perfect candidate for the task.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

Fausto Fasulo: Mr. Isayama, thank you for being with us today.

Hajime Isayama: Thank you for having invited me, and thank you all, because if I’m here today, it’s totally because of my fans who are here today. Thank you.

Fausto Fasulo: We have planned this panel in advance with Mr. Isayama before going onstage. You will see a few pictures and two videos that Mr. Isayama kindly shared with us, which he will comment on. You’ll see that they’re rather interesting. More than just going back on details of the manga, the main idea of this panel is to learn about Mr. Isayama’s working process, how he created this universe and his daily life as a mangaka. We’ll try to give you a glimpse of a mangaka’s intimacy, which we usually don’t know about because a mangaka’s work is often discreet, not to say secret. The idea is to come out of this panel with more intel on how Mr. Isayama works. I wanted to begin by lightening the mood, though I think it’s already light. I spoke about the daily life of mangaka: it was very harsh, with a lot of discipline, especially during the lockdown.

So I wanted to know, isn’t there a sort of parallel? Haven’t you felt what Attack on Titan’s characters lived through when you worked on the series and were literally locked up behind walls?

Hajime Isayama: It’s true that the main themes of Attack on Titan are battle and war. There are links with the work of a mangaka because the survival environment in Attack on Titan and my own universe closely resemble one another. During the series, my position evolved. It’s a bit like the characters who develop in Attack on Titan, so I often like to identify with them. For instance, at the end, the protagonist Eren has to activate titan powers, and it’s a little like me, whose content, as a work of art, got extremely important. As an author, I had to take responsibility for this.

Fausto Fasulo: There’s a question that often comes back in media. How can you explain the impact overseas? Why was this series so popular? And you answered saying there was a theme of lockdown, things occurring behind closed doors, plotting… They are, in the end, universal themes. But for yourself, have you understood why your work impacted the public?

Hajime Isayama: It’s true that people often ask this question, that is to say, why did Attack on Titan work that well, even overseas? And in fact, this story is about people living in a universe enclosed by walls, threatened by the arrival of titans. And this situation can occur in any era, in any country in our world. And that’s why everyone can identify with the characters in this universe and why I believe this work feels at home everywhere.

Fausto Fasulo: And at which point did you understand that this manga was a worldwide hit? That people talked about you on social media, that you had fans everywhere on Earth? When did you realize that something was happening and that your status had changed?

Hajime Isayama: I believe it was really with the anime that it became very popular worldwide.

Fausto Fasulo: And how does it feel daily, with the fans’ pressure? Fans are commenting online, writing mail, and communicating in various ways.

When you started a new important episode, how did you live with it? Did you talk about it to your assistants and your relatives? Did you keep it to yourself? Did you have ways to get it out?

Hajime Isayama: It’s towards the end that it was hard to deal with the weight: expectations became very heavy, and it started to really weigh on me. I didn’t feel able to carry such a burden by myself, so towards the end, I felt the need to ask for the help of others. But in the end, I managed to tell myself that no, it was my duty to carry it all.

Fausto Fasulo: So did you talk about it to your assistants or friends?

Hajime Isayama: To be honest, I didn’t talk about Attack on Titan with my assistants very much. It’s strange. I didn’t talk about the content with them; I think I felt intimidated, which may be why we spoke of dumb things like what manga we read or movies we watched. By the way, yesterday I attended the signing session, and many people came to talk to me about Attack on Titan, but I was shy, so whenever it was mentioned, I didn’t know what to say. I asked them, what movies have you seen lately? or things like that.

Fausto Fasulo: Unfortunately, I have questions about Attack on Titan today. But we can talk about movies you’ve seen as well. By the way, what movies have you seen recently?

Hajime Isayama: It’s not very interesting, but I saw Smile on the plane.

Fausto Fasulo: Smile is a horror movie that also came out in France not so long ago.

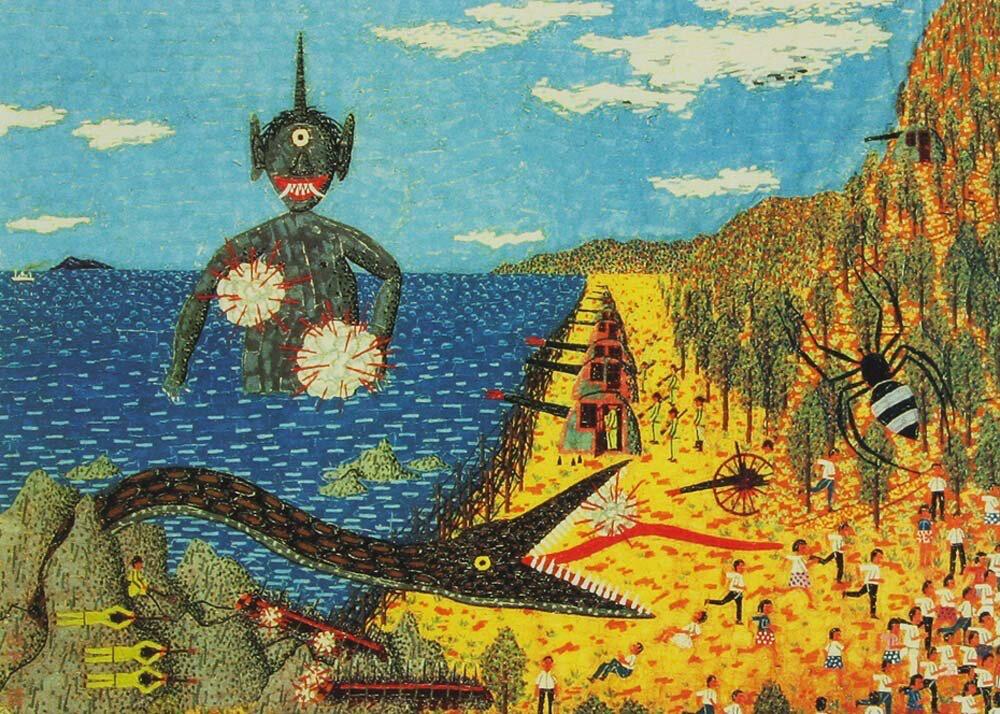

Kaiju by Kiyoshi Yamashita

Now, there’s this picture you wanted to show today; it’s a painting by an artist named Kiyoshi Yamashita. He did what we may call outsider art; he had behavioral issues. He suffered from “savant syndrome” and had a rather mind-blowing artistic ability. What’s interesting is this drawing. I have to apologize for the low quality, as the painting is much more beautiful in real life. Mr. Isayama wanted to show it. He already talked about it not so long ago when he was invited to New York. I would like him to share his thoughts: if he could tell us how he discovered it and what it evoked when he first saw it.

Hajime Isayama: At home, when I was a kid, there was a painting from Yamashita, and I remember that each time I looked at his pictures, I was terrified. It seems that during the war, he tried to flee and did all he could to avoid going to war. I guess he painted the dread of war. When I worked on Attack on Titan, I didn’t think about it at all, but once I finished the last chapter, I remembered this painting and realized that all the parts with great destruction came from it. This painting truly evokes the feeling of despair: even when we shoot the titans, it doesn’t work. This despair is found in this painting, and it was when I first realized, after ending the last chapter, that this painting influenced me.

Fausto Fasulo: Thanks for this great reply.

Now, let’s talk about Mr. Isayama’s workshop, his assistants… We’ll show a video Mr. Isayama directed himself, you’ll see what his workshop looked like, how many assistants there were, and maybe he’ll also be able to tell us more about the organization… It’s very short.

Hajime Isayama: So that’s my workshop, and I deeply regret not having made more videos of it. I only have small bits like this.

Fausto Fasulo: Were there always four assistants as we can see here?

Hajime Isayama: Four at the busiest moments. There would be a huge workload if there were four, and I would be busy. It’s when I had the most pressure. Kind of like the battles, there was a war between my assistants and me.

Fausto Fasulo: As a young author, was it challenging to learn to talk to an assistant when it was your first time?

Hajime Isayama: Teaching assistants… I didn’t know how to explain things or how to teach my assistants, and we didn’t even know if we’d be able to continue the series, to really complete it. It’s kind of like how human beings are unpredictable, the work was also unpredictable. We groped and looked around, we talked about various things, like how the designs in Demon Slayer rock…

Fausto Fasulo: The assistants we see onscreen, were they always the same during the series, or did some other people work on it?

Hajime Isayama: Probably twelve or fifteen in rotation, each assistant coming between one and three days a month.

Fausto Fasulo: Mr. Isayama mentioned Demon Slayer, so I have to ask. We know some mangaka don’t read manga, work a lot and don’t want to be influenced by the trends and works of other artists. If you mentioned Demon Slayer, I guess it means you’re the other kind of mangaka?

Hajime Isayama: Right now, I read a lot, more than ever before. Do you know about narô-kei? It’s a manga genre about good-for-nothing men who get hit by a truck. They believe they died but they’re still alive in a fantasy universe.

Fausto Fasulo: It’s always interesting to see how major works influence each other. Now, as you read more manga, do you read some that take from your own work? Have you ever seen similarities?

Hajime Isayama: I don’t know if there are that many direct influences, I never really found any. Maybe I shouldn’t talk about this, but there was a manga in Jump that got axed. People bit their hands or fought with two swords at once… When I saw all that, I thought that perhaps it came from my manga. But maybe I shouldn’t have told you.

Fausto Fasulo: We know that the editor is essential in the manga industry. You were followed by someone named Mr. Kawakubo, who found out about you and oversaw all of Attack on Titan. How was your relationship? Was he the kind to provide a lot of ideas and advice?

Hajime Isayama: I feel extremely grateful to my editor Mr. Kawakubo. He really helped me when I came up with the project for Attack on Titan. Back then, I didn’t really think I’d become a professional mangaka. But he was the one to convince me my manga was interesting and that I should participate in contests. That’s how it all began: he was the first one to tell me I was right in wanting to become a mangaka. It all started thanks to him, and the series started like that. I am under the impression I grew with Mr. Kawakubo and thanks to him.

Fausto Fasulo: How did your daily relationship go? You published in a monthly magazine, and in an earlier interview, you discussed your schedule. You would pencil for two weeks, ink on the third, and do the last touches on the fourth. Was Mr. Kawakubo present all the time? Did he call in every day, once a week? How did things go?

Hajime Isayama: To begin with, to start each episode, we would do meetings and discuss to plan out the story development, the plot of each episode, and we would decide up to which point, which scene we tell the story each month. After this meeting, for a week I worked on the storyboard, a sort of rough draft of the panels, and then we’d decide what to keep and what to throw away. And then I’d start drawing.

Fausto Fasulo: Did you take out a lot from your storyboard?

Hajime Isayama: With Kawakubo, we discussed ideas, what to keep or take out. And when he’d say that something might be better left out, that’s when our war began. In the beginning, I resisted a lot, but when I read again, I would realize he was right. The beginning was a bit complicated, but after some time, it got better.

Fausto Fasulo: It’s well-known that an editor can intervene in the scenario, but commenting on the drawings is also part of the job. Mr. Isayama, do you remember Kawakubo’s comments on your drawings? Were there points of his drawing style that Kawakubo asked you to improve upon, to change? For example, what about the linework?

Hajime Isayama: He indeed told me several times I should improve on my drawings, and he often told me rather harsh things too, but I knew it was hard to improve and to work to get better. So I said the rough style had its charm. That’s how I defended the drawings he criticized.

Fausto Fasulo: In an interview for a French magazine, you said that at the beginning of your career, the imperfection of your drawing style was a strength, though it was often criticized. But over time, you began to feel bad about your lack of skills. At which point did you finally think you should work on it?

Hajime Isayama: There is a manga that greatly influenced me, Arms, by the artist Ryouji Minagawa. I deeply respect him, and he gave me personal advice, telling me to work on my onomatopoeia. Because if they’re lacking, it lacks impact. His advice helped me a lot.

Fausto Fasulo: There was an exposition in Japan, the last dedicated to your work, the Attack On Titan Final Exhibition, and in the catalog it was written that if you had to redraw the first pages of the series, you’d cut some panels, change the structure… What are some of the scenes you feel like this about, and which you’d do differently today?

Hajime Isayama: I sometimes ask myself those questions, what could I have done, what would I redo if I had to redo it today? To give a few examples, perhaps for Armin, I’d add a line that goes like, “I don’t know how the walls were built,” it might make things easier to understand. Or Eren becoming a titan. Some people said he should become a titan in a less random manner. If I could do it more naturally, I could also explain why he became a titan. I have a lot of regrets like this.

Fausto Fasulo: There are times in Attack On Titan with very few lines, many panels have no dialogue, and on the other hand, some others are filled with dialogue, with a lot of information. Was writing this dialogue difficult?

Hajime Isayama: If there are too many lines, it lacks balance. So I wanted to create contrasts. As for their content, I was influenced a lot by Game of Thrones because the dialogues are so iconic. When I discovered this series, I tried to put the same irony in my dialogue.

Fausto Fasulo: Did you watch the series as it came out?

Hajime Isayama: I believe it was towards season 4 that I began to watch it. My assistants also liked it.

Fausto Fasulo: Were there any other series or books that influenced you as you were writing?

Hajime Isayama: There were so many that it’s hard to cite them all, but maybe Watchmen, District 9… Movies or series that were big hits. But rather than influence, I’d say these works supported me as Attack on Titan advanced.

Fausto Fasulo: Earlier, we spoke about your workflow, notably the storyboard. Did you sometimes want to change the plot at that stage? If yes, what did you do? Stick to the scenario or change it?

Hajime Isayama: It was a case-by-case thing. At the start, I followed the main direction of the story, but there was already a bit of improvisation. Things evolved as I wrote, and that’s how the story became so long. It may be one of the inconvenient aspects of publishing a shônen series.

Fausto Fasulo: With so many characters, did you ever want to do a one-shot? Or want to escape from Attack on Titan and draw something else, even if time was against you?

Hajime Isayama: Yes, at times I wanted to draw something else. But when I worked on the first chapter of part 2, I felt an intense pleasure that I had never felt before. A feeling that I was doing something else. Or maybe because I often did comic stories in School Castes, it felt different.

Fausto Fasulo: Technically, did you also feel a switch where you reached a certain level and could draw things better than in the past? Was there a chapter, a panel that made you proud and think you had gotten better?

Hajime Isayama: I believe I got much better at drawing. But to tell the truth, I didn’t do all the drawings myself. At first, I didn’t have enough money to hire many assistants, so I couldn’t add a lot of screentone: screentone work is that of assistants. The more assistants one has, the more screentone one can have, or when one has enough money, one can hire talented assistants. The fact Attack on Titan was a success allowed me to hire assistants, and that’s how the drawings got better.

Fausto Fasulo: Just a precision for the audience: in Japan, when a mangaka has assistants, he pays them himself, not the editor. So authors that write successful stories can have studios of their own with many assistants, but when one starts out and isn’t successful, it’s more complicated to hire assistants.

Now I wanted to show a video of his workshop. The mood here is serious, we’re talking about work, but it seems there were more light moments, so I’d like you to comment on this, because it doesn’t seem like they were hard at work there.

Hajime Isayama: Work was extremely hard back then. We all liked playing Tetris, so we absolutely had to make time to play, but it was very difficult. Anyways, I think my former assistants will be stunned when I tell them they made great debuts on a French scene.

Fausto Fasulo: Let’s go back to the serious stuff. As the series advanced and you had more assistants, the drawings had more screentone, but also weight and meaning. How did you live this change? As someone who didn’t do well in school and was considered weird when you grew up, how did it feel to become responsible for assistants and write such an important series?

Hajime Isayama: It’s true that in my childhood or teens, I was kind of like an autistic child, by myself. I’m a bit ashamed of this time of my life, where I did a lot of dumb stuff. But even after reaching twenty, I wasn’t very mature, I was still very childish. When I became thirty, I was more of an adult. But it’s probably getting married that made me grow.

Fausto Fasulo: Is it true that when you began, you didn’t think your panels were that precious? That they were simply work material? How does your art feel when you see it in an exhibition now?

Hajime Isayama: It’s true that I didn’t care much for the originals. Some manga authors don’t care about originals, and once they’re published they throw them away. But now I’m happy that my originals still exist: I made them with my own hands. Many authors work digitally these days, so there are no more originals. I believe we’re at the end of hand-drawn originals…

Fausto Fasulo: Do you regret this? Do you still want to work on ink and paper, or switch to digital?

Hajime Isayama: I think I’ll work digitally. These days in the manga industry, we no longer force assistants to work in the author’s workshop since we can work online.

Fausto Fasulo: This masterclass may end with a complicated question. The series is over, people talked about its ending positively, negatively… We won’t debate this. But I think readers want to know what you’ll do now: will you pause, or start a new story?

Hajime Isayama: It hasn’t been announced yet, but I may do something between eight and sixteen pages. I’m not sure it will be good, but hearing the encouragement of the audience, I feel like I have to. I’ll try my best.

We wish to thank all the parties involved in the organisation of this panel, and in particular Mr. Fausto Fasulo, Mr. Hajime Isayama, and his interpreter Shoko Takahashi, as well as all the staff of the Angouleme International Comics Festival.

Transcription: Emilia Hoarfrost

Translation: Emilia Hoarfrost & Dimitri Seraki

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Oshi no Ko & (Mis)Communication – Short Interview with Aka Akasaka and Mengo Yokoyari

The Oshi no Ko manga, which recently ended its publication, was created through the association of two successful authors, Aka Akasaka, mangaka of the hit love comedy Kaguya-sama: Love Is War, and Mengo Yokoyari, creator of Scum's Wish. During their visit at the...

Benoît Chieux, a career in French animation [Carrefour du Cinéma d’Animation 2023]

Aside from the world-famous Annecy Festival, many smaller animation-related events take place in France over the years. One of the most interesting ones is the Carrefour du Cinéma d’Animation (Crossroads of Animation Film), held in Paris in late November. In 2023,...

Directing Mushishi and other spiraling stories – Hiroshi Nagahama and Uki Satake [Panels at Japan Expo Orléans 2023]

Last October, director Hiroshi Nagahama (Mushishi, The Reflection) and voice actress Uki Satake (QT in Space Dandy) were invited to Japan Expo Orléans, an event of a much smaller scale than the main event they organized in Paris. I was offered to host two of his...

Recent Comments