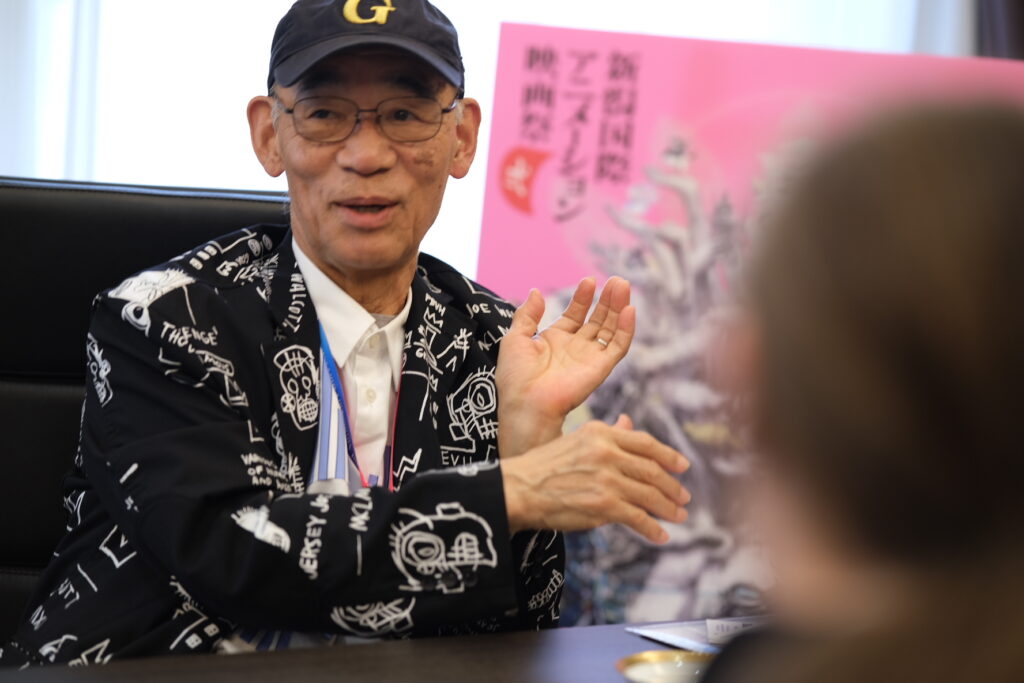

Since his directorial debut on a TV series with Infinite Ryvius in 1999, Gorō Taniguchi has always been one of the most original voices in Japanese animation, known for his affection for science-fiction and his over-the-top stories. When we met him in August 2023, it was to discuss these two sides of his style and career with Planetes and Code Geass, which is celebrating its 17th anniversary on the day we release this interview.

The Gorō Taniguchi we met isn’t just a top-class anime director. A person who never minces words, he has an extensive knowledge of contemporary media and a keen eye for present and future trends. We did not only discuss his works but also the past, present, and future of animation in Japan and the world.

This article is available in Japanese. 日本語版はこちらです

This article would not have been possible without the help of our patrons! If you like what you read, please support us on Ko-Fi!

“Takahata transcended human vision”

So, I believe all of your Sunrise works were made in Studio 4…

Gorō Taniguchi. That’s not quite right. My first TV series, Infinite Ryvius, was made at studio 9, the same studio at which Ryōsuke Takahashi[1] made Gasaraki. After that, s-CRY-ed was made at studio 7, the one that produced Yoshimoto Yonetani’s works like GaoGaiGar, Brigadoon, Betterman… Even though studios 7 and 9 are separate, they both depended from the so-called 3rd business unit. But it changed names, and it’s now the 2nd business unit. It’s easy to make such mistakes… Anyway, that’s where I worked. However, the top producer from there left Sunrise after s-CRY-ed.

Is that so?

Gorō Taniguchi. They went independent and created Studio Manglobe. But all the people under them ended up scattered all over. In my case, I was without a job, so the president of Sunrise at the time, Mr. Kenji Uchida, assigned me to a new project at studio 2. It’s the one that did Yoshiyuki Tomino’s[2] Overman King Gainer, and that project was Planetes.

Actually, the main staff of Planetes didn’t come from s-CRY-ed but from King Gainer, right?

Gorō Taniguchi. That’s right. Although a lot of the staff that wasn’t in-house, such as the editing and sound effects teams, had worked on s-CRY-ed.

All that staff in common, was it because it was made at the same studio?

Gorō Taniguchi. That’s it.

The King Gainer team was full of young and talented people, right? Did you feel that when working with them?

Gorō Taniguchi. They were very talented, of course, but there was one problem: they had been working with Tomino until then, so they were used to his way of doing things. I always had to tell them that maybe Tomino did things like that, but that I did things like this, and always explain why it had to be so… But the worst was that on top of it, some members of the staff had originally come from Ghibli.

Oh, so they were also used to Mr. Miyazaki’s approach… (laughs)

Gorō Taniguchi. Exactly. They were used to that so-called Ghibli style… I had to tell them to do things logically, not just to go with their instinct. I had to tell them about everything all the time, which was a bit tedious.

That logic of yours, does it come from Ryōsuke Takahashi’s influence?

Gorō Taniguchi. It does. I consider myself one of Director Takahashi’s disciples, after all. However, I’d say the person who’s influenced me the most would be Isao Takahata[3]. It’s not like I’ve ever worked under him, it just came from watching his work as a normal viewer, reading his books, and understanding what kind of person he was and what he had in mind when directing. So I’ve never been in direct contact with him. But in Planetes’ case, I called for the help of episode directors I already knew pretty well to make things go more smoothly.

What’s your favorite Takahata work?

Gorō Taniguchi. I love all of his works, but… If I had to say which one had the most impact on me, it’d be Heidi, Girl of the Alps[4]. I saw it as a kid at first, and then again when I was in high school, it left a big impression on me.

I understand very well. In my case, my favorite World Masterpiece Theater series of his would be Anne of Green Gables[5]…

Gorō Taniguchi. I love it too. Around that time, he also completed Gauche the Cellist[6], right. But it wasn’t aired on TV or shown in theaters, so I looked very hard to be able to watch it. And when I finally managed to, it struck me just like Heidi had. It really hit me hard. I had no idea what I should do to be able to reach such a level.

But ultimately, I love The Tale of the Princess Kaguya. It’s his last work, and it made me feel like he had transcended human vision and reached a place normal people can’t go. When creators reach the end of their lives, I believe one of two things happens to them: either they lose interest in anything other than themselves, or they go the opposite way and start viewing things completely differently. Miyazaki ended up making it all about himself, whereas Takahata has gone somewhere above the clouds. (laughs)

I feel the same. (laughs) So, what did you think of How Do You Live?

Gorō Taniguchi. In The Wind Rises, it felt like Miyazkai portrayed himself a bit too positively, so this time he probably wanted to show the more messy parts of himself as well. In that sense, it’s become a sort of cult film. (laughs) For me, these two films come in a pair.

(laughs)

“Yuriko Chiba’s one of a kind”

Ok, let’s get back to Planetes. It was your first collaboration with Ichirō Ōkouchi[7], right?

Gorō Taniguchi. It was.

Can you tell us a bit about how you met and about your collaboration?

Gorō Taniguchi. At first, Producer Jun Yukawa asked me how I felt about letting Ōkouchi handle the script. And I refused, I thought it would be impossible to work with him. The reason for that being that I had seen the first episode of Gainer which he had written, and I didn’t want someone who wrote things so complicated. I said that to Yukawa, who told me that I got it all wrong and brought me both Ōkouchi’s script and Tomino’s storyboards and asked me to read them side by side. I did just that, and I had to admit that my impression of Ōkouchi was wrong. (laughs) The script was actually so straightforward! I have no idea how on Earth it became so complicated, but it didn’t come from the script. So in the end I went along with him.

In the end, Mr. Ōkouchi became the only scriptwriter on Planetes. Why is that?

Gorō Taniguchi. Well, the first reason is that he was recommended by the producer. The other is that I had never done such a collaboration before, so I wanted to try it out. Also, something I realized once we started working together is that Ōkouchi’s got a very good business sense – I mean that in a good way. He understood what was important in the project, what had to be protected at all costs, and he acted consequently. Also, he didn’t try to push his own opinion too much. If he had, things might have become difficult. (laughs) But we’re pretty compatible. So I didn’t have any reason to look for anyone else.

I see. Planetes was also your first work with Ms. Yuriko Chiba[8].

Gorō Taniguchi. As a main staff member, yes.

How was she selected for character design?

Gorō Taniguchi. Actually, Planetes wasn’t really the first time I encountered her work. She participated in the design contest for s-CRY-ed, but the designs she suggested were close to what she did on Planetes, and that wasn’t quite what we wanted to go for… But then for Planetes, I remembered what she had done and thought she might fit the bill. Her style is realistic, but not like Katsuhiro Otomo’s realism: there’s more sensuality to her characters, both men and women… Otomo’s art takes too much from Moebius, so sometimes you wish he’d make things a bit more romantic. You get that feeling like, can’t the girls be a little bit cuter? (laughs) I think the mangaka who nails that the best would be Naoki Urasawa. Things like his first manga, Dancing Policeman, are very characteristic of that time where everybody was influenced by Otomo, but he actually manages to make the girls look cute and the boys look cool. And I felt that Yuriko Chiba’s art had the potential to create the same feeling, but in animation.

And as an animator and animation director, what’s the best thing about Ms. Chiba?

Gorō Taniguchi. As an animator, she’s one of a kind. But I also realized that has its problems: actually, she’s way too talented. Because of that, other animators have a hard time catching up to her level. Since we work as a team, it’s important to strike a good balance, and it might be difficult with someone as good as her.

However, as a designer, she has the great merit of not using any existing anime or manga for inspiration. So for instance, what I asked her to use as reference for the characters was a collection of pictures of foreign actors… And she really responded to it, which was a huge help.

So you used that as reference rather than the original manga?

Gorō Taniguchi. That’s right. So for example, the main characters work at the Debris Division. Consider the Division Chief: with his body type, we had to use real actors as reference. He’s got this very American body type, where the legs are pretty stretched-out but the upper body is rather fat. You don’t see such people often in Japan. Moreover, if you observe actual people and use them as models rather than the stylized characters of manga or anime, the end result is a more distinct, unique character.

So that’s how you managed to make the cast so international.

Gorō Taniguchi. Yes. For example there’s Lavie, who’s Indian, and we thought about making him slim and a bit sheepish. (laughs) Such other character would be Taiwanese, so they should have that look, and so on. I’m happy we managed to make the cast so multicultural.

“It was incredible for both the series and me”

Planetes aired on the NHK, was that decided from the start?

Gorō Taniguchi. It was decided from the start that it’d be aired on NHK’s satellite channel. The reason is that Planetes doesn’t quite fit in line with what’s considered “profitable” in Japanese animation. It doesn’t have any robots, nor does it have the cute anime girls otaku like. They’re not in space to fight monsters either… (laughs)

Don’t otakus like hard-SF?

Gorō Taniguchi. Maybe that’s the case with foreign otakus, but those here in Japan don’t really watch SF just for the SF aspect of it. Since roughly the 1990s, even in works that seem like SF, the SF aspect is no longer the core. What’s become more popular since then is fantasy, and what we used to call “bishōjo anime”, – nowadays it’s moe anime – where it’s all about watching girls do their stuff. So something like Planetes, hard-SF without any pretty girls or boys wasn’t going to get any viewers. Since it wouldn’t make any profit, NHK took us on.

Did the fact that it was aired on NHK have an impact on the production? Like the scheduling, the workflow…

Gorō Taniguchi. I was actually pretty worried about that, but the staff dispelled all of it. Planetes aired on NHK’s BS2, so a specialized satellite channel that ordinary families wouldn’t watch. And that might have played against us: it wasn’t the kind of show the staff’s families could watch, it didn’t even show up in magazines, so it could have made it difficult to get that team feeling going. Fortunately, the cast and staff of Planetes weren’t that kind of people. They did what they had to and showcased their talents whenever they could. It was incredible for both the series and me.

They wanted to create their own masterwork, is that it?

Gorō Taniguchi. Yes, you could say that. I was also very happy that we got support from the producer side: I’ve never forgotten the producer from NHK, Tomoyuki Uehara. He was an otaku as well. (laughs) So he understood what we were trying to do.

Comparing the anime and the manga, you made a lot of changes, notably to the plot structure. How did you decide to do that?

Gorō Taniguchi. When it was decided that we’d make the manga into an anime, I realized it wouldn’t work. Not for a TV series, at least. It was too short, so we had to redo all of the worldbuilding, add original characters to make the story progress, and so on. When I first met Makoto Yukimura, the original author, I had prepared all kinds of stuff and made a presentation: because of such and such, he had to let us make changes. (laughs) We needed this new character, and this new development, and all that. (laughs) He agreed. But then once it was all over, I told him he had made the right decision, and his answer was, “Well, you didn’t seem like the kind of person who would listen anyway”. I don’t know if he was joking or not, but maybe I went a bit overboard. (laughs)

Who created the original characters? Was it you, or Mr. Ōkouchi?

Gorō Taniguchi. Some of them are my creation, and then Ōkouchi would also make his own suggestions.

I’m particularly curious about the ninjas…

Gorō Taniguchi. Oh, the ninjas? I think that was Ōkouchi’s idea. He loves ninjas. (laughs) At first, I came up with a story that went like this: there’s this mangaka on the moon, and he loves baseball, so he creates his own team and plays baseball all day. But it’s on the moon, so because of gravity and all that, I thought about all the ridiculous jumps and moves they would do. (laughs) But then one day his editor comes and forces him to draw manga because he’s late on his deadline…

Problem is, Japanese viewers wouldn’t necessarily relate to that story about a mangaka and his deadlines. That would have been even worse with overseas audiences, and there’s the issue of baseball: there aren’t a lot of countries where people would have gotten the joke. So we thought about something more international, but what would fit the bill? And everybody we asked said ninjas. (laughs) So that’s how it ended up that way.

So you had international audiences in mind from the start?

Gorō Taniguchi. Yes, from the start. It was broadcast on satellite, so it wasn’t shown just in Japan, but also in every Asian country which had satellite channels back then. And then after the first broadcast, it was decided that it would be shown in Europe and America as well.

“SF has always been a part of me”

Nowadays, if the anime adaptation isn’t exactly the same as the manga, fans often complain. But the Planetes anime is totally different from the manga… Do you think such a show could still be made today?

Gorō Taniguchi. Today, I think some people would approve and some wouldn’t. I don’t know if it’s a good thing or not, but they’d probably let me go away with it… Or rather, I think fans have already given up on me. It’s not like I wanted it to be that way, though. (laughs) I do my best to understand the client’s order and follow the original work, but some fans will always say things like “One Piece Red isn’t One Piece!”, so… It’s not like I’m ignoring the fans and changing the original work just as I like. It’s just like that following every little detail of the original is absurd. It’s not my job, and if I did that, I don’t think I’d have one in the first place. (laughs)

These things change with time, of course. I first felt the winds shift when I saw the first episode of Detective Conan. It really shocked me to see how much the storyboard just copied the manga. I had always been told not to do that, and that’s just what they did! Back when I was doing the storyboards on Honey and Clover, we were advised to closely follow the manga. But I decided to go against the flow: there was no way I’d just copy the manga, so I did my own thing. But that was probably the last time such things were possible… After that, it really depended on the client. For instance, on Haikyuu!!, I was told that we could use both the manga’s pictures and also do some of what we wanted, so I could relax and do things my way. In the end, it’s all about balance.

And it’s really difficult, isn’t it? If the anime staff just does what they want, they might go too far and it’ll become something completely different; but it might become a unique piece of animation and sell well, so… it’s hard to tell which is right. But basically, what I want to say is that animation isn’t inferior to manga, novels or games. Film, comics, novels, games, each of them is a different form of expression, with its own specificities and advantages. Even each individual game is different from the others. But what’s important is to be aware of your responsibilities. If a staff member does their own thing and that leads to a project’s failure, they’ll have to take responsibility, and might end up leaving the industry. Manga artists are putting their life on the line. So anime staff must be ready to take the same amount of risks.

Going back to SF, were you already interested in it before Planetes? If so, any works or authors in particular?

Gorō Taniguchi. I’m part of the generation that just grew up with SF. Back in elementary school, I’d read stuff like kids’ versions of novels by Asimov, Heinlein, Hogan, and in terms of Japanese authors, I’d say the work of people like Sakyo Komatsu, Yasutaka Tsutui or Shin’ichi Hoshi was always there somewhere besides me. In terms of TV shows, I’ve seen things like Ultra Q, Twilight Zone… Since the moment I saw Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, I’d say SF has always been a part of me. Even today, I still check out the books that receive the Hugo and Nebula awards.

Because of that, if Japan’s SF and tokusatsu hadn’t gone so cheap compared to overseas productions, maybe I’d have gone to become a tokusatsu or special effects director. As time went by, budgets went down and it became so cheap…Nothing after Ultraman has ever gotten to that level again. Animation’s different, because it felt like there were still so many possibilities. I also felt that in the staff I worked with. So that’s why, when I did my first original with Infinite Ryvius, I forbade anything that’d make it look like Gundam. Gundam’s approach was developed by Gundam’s staff at the time of the first series, and we had no relation to that whatsoever, so we didn’t have to copy them. I wanted to create our own world, centered on ideas like orbits and zero-gravity.

These were good times, right?

Gorō Taniguchi. Indeed they were. It’s a shame that Japanese people grew to prefer fantasy to SF, and works where you don’t have to think too hard. On the other hand, a good thing is the development of CG. It’s opened a lot of new possibilities.

Did you do any research on space and things like that for Planetes?

Gorō Taniguchi. I did. Before we started writing the script, we asked someone named Kokura to teach us about space technology and physics to help out with concept designs and worldbuilding. He made a course for Ōkouchi, Chiba and I. Thanks to that we could begin work with the basic amount of knowledge required.

I was just about to ask about Mr. Kokura. Why did you set your sights on him?

Gorō Taniguchi. Kokura originally worked in animation and then went over to tokusatsu and visual effects, so he knows best how to communicate scientific ideas to creative staff. It wasn’t like a real lesson with some professor reading out a physics manual, where we wouldn’t have known what was important to remember and what we could leave aside. Kokura knew what kind of work we were doing and what we needed. So he first explained everything we needed to know, and on top of that, if we had even more specific questions, we went to see specialists: we went to do some research at JAXA, the center for space development in Japan.

Mr. Kokura also designed spaceships, right?

Gorō Taniguchi. That’s right. Not just spaceships, but also the Tandem Mirror Engine. There was no documentation whatsoever about that at the time, so Kokura went with his imagination, and he turned out to be right.

I believe that Planetes is a really important work. For instance, without Planetes, things like Gravity[9] would never exist…

Gorō Taniguchi. Actually, I have things I want to say about Gravity.

How do I put this… The Japanese distributor didn’t invite me to any screenings or anything. (laughs) But come on, any way you look at it, the plot is… It doesn’t have to be me, the least they could have done was inviting someone, either from the staff or Mr. Yukimura or something. Didn’t they know about us? That’s unbelievable… I was kinda mad, what the hell were Japanese journalists doing? So I had to pay to go see it. (laughs) But well, as a film, I see what they were going for, and I think it’s a good film. Debris probably don’t fly that slowly, but if they had made them faster they wouldn’t even show up on screen, so they probably had no choice… So in that sense, I understand their choices pretty well.

Do you know about Mitsuo Iso’s The Orbital Children[10]? Do you think it was influenced by Planetes?

Gorō Taniguchi. I know about it. I heard this from members of its staff: it seems like Mr. Iso initially wanted to call it Extraterrestrial Boys at first. However, he was told about the famous episode of Planetes called “The extraterrestrial girl” and suggested they change the title to Extraterrestrial Boys and Girls [original Japanese title]. So I don’t think Iso ever thought of Planetes, it’s just that we ended up taking the same approaches and having the same ideas. But well, I haven’t asked him directly, so I can’t tell whether it’s true.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

“As a director, you have to take care of your own staff”

Thank you very much. Now, let’s move on to Code Geass.

I believe the show was your and Mr. Ōkouchi’s idea, but can you tell us how it started?

Gorō Taniguchi. Actually, it started without me. The producers of Planetes, Mr. Yukawa and Mr. Kawaguchi, first talked about it with Ōkouchi. It was around the end of Planetes’ production, and things were getting pretty busy on my end. And so, during one of the last mixing sessions, Kawaguchi came to see me during the break because he had something to talk about, and what he talked to me about would become Code Geass. I took the order and started gathering people. Ōkouchi and I started writing plot drafts and did all kinds of meetings for some time. At the end, Ōkouchi brought all of that together in a single document for TV stations, which Yukawa and Kawaguchi went to present. And as our hopes were at their highest, they came back to tell us it didn’t work out and that we had lost to another project. There had been two projects in competition: ours and one brought by studio Bones. We lost to that one.

Oooh, I see. And so you rewrote that initial project?

Gorō Taniguchi. Since we had lost, it was decided to retry it on a late-night slot. But Ōkouchi thought he couldn’t meet the producer’s expectations in such conditions, so he wanted to scrap it, pretend it had never happened. But I had already gathered many people, including CLAMP[11], so my position was a bit delicate…

So CLAMP was already there at that stage?

Gorō Taniguchi. They were. That’s why we were so surprised to see that the project didn’t get sold.

Also, as a director, you have to take care of your own staff. The project hadn’t worked out, but I still had to give them some work, because it’s my job to support them, help them earn their bread. I had brought staff from my previous work Gun X Sword like Takahiro Kimura[12], Kenji Teraoka[13] and Reiko Iwasawa[14], to work on this, and I couldn’t just leave them hanging, so in the end Ōkouchi agreed to stay. We reworked the project and it became the Code Geass we know today.

Was it already supposed to be called Code Geass at first?

Gorō Taniguchi. At that time, it was only called Geass, without anything else in the title.

What was it about? What was your intent with this project at first?

Gorō Taniguchi. It began like this. There’s this military school in some military dictatorship, where two young boys become friends. But one of them is raped multiple times by a teacher, and they plan to kill him. But of course, if they did that they’d be executed, so they start thinking about what they can do. They could either try to get some ability, or rise up the ranks so high that they could just kill him without consequences or send him to some battlefield where he’d be sure to die. That’s more-or-less what it was like.

The soldier part remained in Code Geass, but what about all the nobility? Were you perhaps influenced by Legend of the Galactic Heroes[15]?

Gorō Taniguchi. Legend of the Galactic Heroes? I see… Well, both Ōkouchi and I had read the novels and watched the anime, but this is the first time someone makes that connection. (laughs) Really, that never occurred to me. By the way, my favorite character is Yang Wenli.

Li Xingke from Code Geass does resemble Yang Wenli a bit…

Gorō Taniguchi. Ahhh! (laughs) Since he’s not that important of a character, we could follow our own tastes.

Regarding your question about nobility, I think that came from CLAMP. Also, there’s the fact that we had the show take place on Earth. At first I wanted to have it happen on a completely different planet, but even if foreigners watched it, I was afraid the Japanese wouldn’t because it’d have become science-fiction. So instead we decided to make it happen in Japan. For the antagonists, we thought about Australia or Africa, but America was easier to understand for Japanese audiences, so we decided they’d come from there. But just making it Japan against the US would have been no fun, so we decided to have the English invade America. (laughs) Before that I thought about Spain or Portugal, that it might be funny if they had conquered America. (laughs) Hopefully the English got the joke. (laughs)

I don’t know if Code Geass is popular in England… (laughs)

Gorō Taniguchi. I don’t know either. But I’m sure they’d understand. (laughs)

The relationship between the two main characters, Lelouch and Suzaku, also reminds me a bit of the one between Char and Amuro in Gundam, but…

Gorō Taniguchi. Aah, I don’t really agree. Unlike Char and Amuro, they don’t meet on the battlefield: they’re more like childhood friends who spent a summer together. That’s been a foundational element in their identity, a sort of paradise they both look back to. So I think it’s different.

Ok, so leaving aside their relationship, doesn’t Lelouch feel a bit like Char? He’s from the nobility, he wants revenge for his family… Also, about Suzaku, he’s got a white robot, isn’t that a main character thing?

Gorō Taniguchi. There’s some of that on the surface, but that’s not the core of Lelouch’s character. But it’s true that there are a lot of similarities. However, if I had to pin it down, I’d say it’s closer to Star Wars than Gundam. I wanted Suzaku to be in a white robot at first and then a black one at the end, just like Luke Skywalker’s clothes. And then, well, it’s not like I wanted the main character to be a Darth Vader copy, but I wanted him to start out dark and gradually turn white, slowly getting redeemed. So I think it’s more like Star Wars.

So who’s Princess Leia?

Gorō Taniguchi. That would be Nunnally. She’s the third member of the trio, and her position never really changes. Oh, and to be clear, I’m not talking about Leia in J. J. Abrams’ Star Wars. (laughs)

Now that you mention it, it’s true that Lelouch and Char resemble each other – I get it now. But I think that’s because it all comes back to the monomyth – or the so-called hero’s journey. Still, as I told Ōkouchi back then, the base pattern isn’t Gundam but rather Kamen Rider. Just like Lelouch, the boss of Shocker begins by creating an evil organization, but by sheer bad luck his childhood friend becomes Kamen Rider and comes to destroy him. (laughs) No matter how well he plans his strategies, he’s always crushed by Kamen Rider’s power. (laughs) That’s the sort of image we had.

“I managed to make Code Geass become special”

I see, thank you very much. (laughs) Even though Code Geass is a Sunrise work, Hajime Yatate doesn’t appear in the credits, why is that?

Gorō Taniguchi. Originally, Hajime Yatate is a shared pseudonym for Sunrise as a company and all the freelancers working with it. However, at some point it became entangled with Yoshiyuki Tomino and Ryōsuke Takahashi, who wanted the rights on their works. For instance, in Gundam, both Hajime Yatate and Tomino are credited under “original work”. So Sunrise’s employees progressively started to think the pseudonym just applied to them.

It was like that on s-CRY-ed, even though I asked them not to credit Hajime Yatate, precisely because it had just become a stand-in for Sunrise, and because it felt out-of-date. s-CRY-ed’s original project was written by me and the scriptwriter Yōsuke Kuroda, so having Sunrise credited for it would have been weird. I had a few fights because of that. I tried it again on Code Geass, and this time they agreed to drop it. Now, Sunrise is just a brand name and the actual company has become Bandai Namco Filmworks, and they’re still using Hajime Yatate, so a lot of the people working there still think it’s a pseudo just for them… If they had used it on Code Geass, Ōkouchi and I wouldn’t be involved in it anymore. So I’m very thankful to the people from Sunrise at the time who agreed not to credit Yatate.

So in that sense, Code Geass is special among Sunrise’s works.

Gorō Taniguchi. Right. I managed to make it become special, because it made lots of profits for them.

Going back to CLAMP, at a recent event dedicated to Takahiro Kimura, you said that you selected him because you thought his style fit CLAMP’s. Could you explain what you meant? Why did you think that way?

Gorō Taniguchi. The thing with CLAMP is how they draw proportions. You can’t draw such elongated bodies with an approach like Otomo’s. So you need someone with a different style – but also who doesn’t make the proportions so exaggerated it looks weird. (laughs) Characters have to look cool, and the overall thing stylish – but not something like Eiichirō Oda! His style doesn’t really fit Geass. And then, on top of that, you need to add some unique quirks, things like giving big breasts to this character, or think about what a character would look like from all sides… Basically make them such that collective work is possible. That’s very important, especially on TV series. Finally, something like Code Geass needs the contribution of many animators, so you need someone whom all these animators look up to. The person who met all of these criteria was Kimura.

There’s another good thing about Kimura which really surprised me. Among all the animators I’ve met, he was probably the one who knew the best how to read scripts. Basically, he’d just have to read the script to know how a character should act, or how cute the heroine should look…

So just by reading the script, the animation would become better…

Gorō Taniguchi. That’s it. For example, even if he hadn’t seen the Harry Potter movies and just read the novels, Kimura would know that Hermione has to look cute, and would draw her in a way that fits the book. And then he’d make Ginny Wiesley cute as well, but in a different way and just as much as needed. His ability at doing that was outstanding, and just with that he managed to make things he worked on popular. Whereas in Yuriko Chiba’s case, she often references actors. So I had Kimura create Geass’s foundation, and then there were yet more talented people to build on it: Yuriko Chiba, Eiji Nakada and Seiichi Nakatani, who served as main animators.

There’s also a lot of fanservice in Code Geass. Was that one of the reasons why you selected Kimura? In general, how do you approach fanservice?

Gorō Taniguchi. In film, the erotic and the grotesque represent two very important factors to create appeal. Using fanservice for that is perfectly normal. However, the thing with fanservice is that it’s subjective. You can make too much of it and end up ruining it – it takes so much room it’s not “service” anymore, it’s just self-indulgence. That’s why I make sure to tell staff not to get it wrong, not to go too far or mistake what’s appropriate and what’s not. It’s still necessary to make the characters more appreciated and to make the viewers have fun, but I don’t think you should ruin the themes or the characters by adding fanservice that just doesn’t suit them. So in that sense, fanservice isn’t the first entry in the “must-do” list – it’s the second or the third at best.

As for Kimura, he understood all of this without having to be told anything. He understood things so well he’d add things I wouldn’t have, things that can only be expressed through drawings. So for example, if it were just me, I’d make breasts normal-sized or rather small, but Kimura would just make them bigger and bigger. (laughs)

Ah yes, I get it. (laughs) Talking of fanservice, Code Geass is also famous for the Pizza Hut collaboration. Was that a constraint for you? Or did you take it as an occasion to have fun with the characters and world?

Gorō Taniguchi. At first it was something the producers demanded. But it didn’t really fit Code Geass. Why in hell would they always be eating pizza? (laughs) But since we had to go along with it, I figured we should go all the way. I started having fun with it, and the rest of the staff also got on with it as well. (laughs)

“Code Geass wasn’t really a priority for Sunrise”

Thank you very much. (laughs) I believe Code Geass had a pretty difficult broadcast history, but can you tell us what happened?

Gorō Taniguchi. Well, it wasn’t really a priority for Sunrise in the first place. So even though all kinds of people were gathered for it, the conditions we were in weren’t really appropriate. We used some space in another studio, and some space in a disaffected convenience store. We did our best with what we had, but as could be expected, we quickly reached our limits. As early as episode 8, I thought we should just give it up. (laughs) The conditions in the studio were no good, which meant we couldn’t deliver on the quality viewers expected. As a professional, that felt pretty bad. But the producers told me to wait and hang on, because we had made a lot of fans already and that they were ready to give us the time. So they talked with the business division and Sunrise agreed to properly support us. So first we aired the first part, took a break, got our act together and reorganized our studio. We had no toilets, no place to do meetings or check the footage or anything. The writers’ room was just some room we rented in a nearby apartment. That’s how bad it was. Once we had gotten a proper place to work in, we thought we could go back to work and do things the proper way. But then we ran into another problem. It ended up selling way too well, you see, so we made some game and merchandise and everything, which meant we couldn’t work on the actual series. The TV station started getting hyped up as well because all of that made money, so they decided to change the broadcasting slot. But that only caused more trouble, because it ended up changing the audience as well… It was one hell of a mess.

You also reset the story in R2. Why did that happen?

Gorō Taniguchi. A big factor was the change of the broadcast time in Japan. At first, the sequel was supposed to air as is in the same timeslot. But since it got so popular, it was decided to move it to a more popular timeslot earlier in the evening, but that worried us because it would change the audience. So we had to remake everything as if it was a new show, because if we didn’t the viewers wouldn’t have gotten what it was about. It’s like a Netflix original having its second season on Disney+. (laughs) That’s the situation we were in, so we had to redo everything from the start, but there were also the fans of the original who wanted to see a sequel, so we tried to find a middle-ground that would please the two, and it became R2.

Did you have any other plans for how the story should continue before that happened?

Gorō Taniguchi. I did, the story was supposed to go in a different direction, but because of what I told you, we couldn’t do it. But I did plan to make a direct sequel: Lelouch would be believed dead, but he’d actually have been captured and treated as an A-class terrorist, locked up in a special room under the sea from where he’d never be able to escape. That’s how it would have gone. By the way, I reused this idea in Active Raid: in the second season, the first time you see the bad guy, he lives in the sea. So I kinda copied myself. (laughs)

“Every new work is a challenge we need to overcome”

In a way, you could say Code Geass came at the tailend of the golden age of hand-drawn mecha. But now, you’re working with studio Polygon. So what do you think about the current state of CG animation and its possibilities for the future?

Gorō Taniguchi. First, I believe that Japanese hand-drawn animation has already almost reached its peak. For me, the peak of 2D anime is Hiroyuki Okiura’s A Letter to Momo. Now, the next big development in 2D animation is in compositing, visual effects and coloring – all these sections are progressing very quickly. It’s the same in CG.

Then, talking about CG, the problem is that Japan can’t invest as much money in it as other countries, so even though we’d like to do lots of things, we’ve fallen behind. As a result, we’re in a situation similar to that of 2D animation, working with what you might call “limited CG animation”. By that, I mean giving priority to expression – if we actively go in that direction, something could really develop. Right now, CG’s technical level is way behind that of hand-drawn animation, but that’s a matter of course. It took decades for hand-drawn animation to reach its current level. But CG can build on hand-drawn animation’s know-how, so maybe it can catch up in a shorter time.

But actually, you could say there are multiple ways of doing CG animation – which means there are that much more possibilities for evolution. One is to think it up in your head first and create the movement, and the other is to trace over motion capture shots to do something closer to live-action. What we’re doing at Polygon right now is using the first method, while still looking at video references for shots that might seem odd. With this, we’re trying to challenge our possibilities and rival hand-drawn animation. Basically, we’re trying to repeat the history of Japanese animation all over again. Through that kind of trial-and-error, new techniques and styles might emerge in hand-drawn animation as well. I hope our experiments bring new developments for Japan’s hand-drawn animation.

You mentioned Japan and the rest of the world, but nowadays American CG films take a lot of inspiration from hand-drawn Japanese anime.

Gorō Taniguchi. They absolutely do. There’s things like Spiderman: Into the Spiderverse[16]…

Do you think it’s possible to come up with a new way of combining 2D and 3D?

Gorō Taniguchi. To be honest, I’m really jealous. They got to do it first. The Americans are really borrowing from everywhere they can, and so they manage to blend together their own methods with a Japanese aesthetic… And it’s not just Spiderverse: every new work is a challenge we need to overcome. I’m thinking of things like Arcane[17], Wolfwalkers [18] or Long Way North[19] . Things like that are very exciting, and we’re living in interesting times.

Also, Chinese animation has gotten really good recently, and the number of works is also increasing…

Gorō Taniguchi. Yes. Something like The Legend of Hei[20] might be rough around the edges, but it’s so powerful and energetic. They got what makes animation so fun. On the other hand, hasn’t Japanese animation gotten too refined? Maybe we should do rough things like what the Chinese do. There’s a charm that you can only reach by being rough, shouldn’t we look for it? I wish people in Japan stopped making everything look like Ghibli. (laughs)

In the first place, the good thing about Japanese animation is how varied it is.

Gorō Taniguchi. Yes, I agree. There are all kinds of works and styles, and I want that to continue. Whereas the problem with American animation is the stories: they never address political or social themes. So all the stories end up similar. It’s the same in live-action, so maybe that’s due to political or social problems over there, but I’d like them to make stories more diverse. So I want influences between Japan and the US to go both ways. The same with China, or Korea – I want everything to influence everything else. Even France, you’re the country of Charles-Émile Reynaud and Émile Cohl[21], you’ve got such a long history with animation that I wish people looked at your works more.

There’s a lot of stuff happening in French animation today as well.

Gorō Taniguchi. Yes, when I see something, let’s say from France, it makes me excited, so I want to give that back and influence them in return. I hope such relationships would develop. Basically, what I’m trying to say is that I wish that animation can completely break away from national borders in the future.

So we talked a lot about overseas works and fans today, and what’s special about your works is how they’ve always been very popular outside Japan. Why do you think that’s the case?

Gorō Taniguchi. First, I’m very thankful for this. Then, I don’t have a definite answer, but all this time I’ve been trying to do things that don’t only appeal to Japanese otaku. And so I might have found an audience overseas. I’ve been doing this as early as Infinite Ryvius, and even more clearly on s-CRY-ed and Planetes. It’s a statement I’ve been trying to make: what we should consider as our competitors aren’t other animated works. It’s rather live-action series, news and sports programs that also air on TV, but also music and video games: all of entertainment. And that doesn’t just apply to Japan, but to the entire world. I realized that the first time I went overseas, to the Anime Expo in the US.

Also, the Japanese market is shrinking, the population is decreasing… We have to go worldwide. In Japan, we talk about the “supremacy of animation”, but I hate that expression. It’s like we’re trying to draw limits for animation. Our partners and rivals aren’t just other animated works from Japan. I wish our works were brought to the entire world, even if it’s just a few of them. Because I think that even great masters who haven’t been trained in animation like Ryōsuke Takahashi and Yoshiyuki Tomino have left some things undone. Taking up that challenge is a duty that I and the entire anime industry has to fulfill – we have to return to them all they gave us. We can’t tell if we’ll be able to do it, but if we don’t even try, nothing new will open for those coming after us. Whereas, among those who have started as animators, there are people opening new ways: in my generation, there are people like Mamoru Hosoda, Hiroyuki Okiura, Mitsuo Iso… I have to do the same, open a new path different from theirs. Everybody’s working hard in their own way, which makes me think that Japanese animation is still doing well and has a bright future ahead of it. If people overseas could feel at least a part of that, it would make me very happy.

Notes

[1] Ryōsuke Takahashi (1943-). Director, producer. One of the most important directors associated with studio Sunrise, he is known for pioneering so-called “real robot” on series such as Fang of the Sun Dougram and Armored Trooper Votoms. Despite having begun his career in the early 1960s, he is still active as a director to this day.

[2] Yoshiyuki Tomino (1941-). Director. One of the most important directors in anime history. Starting his career on Astro Boy, he is most famous as the creator of the Gundam series and one of the greatest SF creators in Japan. In recent years, he has been busy on the Gundam: Reconguista in G series, after which he is rumored to maybe retire.

[3] Isao Takahata (1935-2018). Director. One of the most important and influential Japanese animation directors and co-creator of studio Ghibli. Active since the late 1960s, Takahata’s work was particularly known for its extreme realism. Most important works include Heidi, Girl of the Alps, Grave of the Fireflies, Tale of the Princess Kaguya.

[4] Heidi Girl of the Alps. 1974 TV series, Nippon Animation, dir. Isao Takahata. Isao Takahata’s first of three World Masterpiece Theater series, based on Swiss novelist Johanna Spyri’s Heidi novels. One of the most influential TV shows in anime history, its groundbreaking depiction of daily life and its staging, made possible in large part by Hayao Miyazaki’s work on layouts, have earned it constant praise since 1974.

[5] Anne of Green Gables. 1979 TV series, Nippon Animation, dir. Isao Takahata. The last of Takahata’s three shows for the World Masterpiece Theater series. It follows orphan Anne Shirley from 10 to 17 as she is adopted into the Cuthbert family in Prince Edward Island, Canada. It was an extremely difficult production where Takahata’s extremely high standard had a toll on the schedule and staff’s well-being.

[6] Gauche the Cellist. 1982 movie, Oh! Production, dir. Isao Takahata. An independent production directed by Takahata and solo-animated by studio Oh! Production’s Toshitsugu Saida. Adapted from a short story by Kenji Miyazawa, it tells the story of the cellist Gauche who is taught music by various animals. One of Takahata’s least-known works, it is also among his most poetic.

[7] Ichirô Ôkouchi (1968-). Planetes and Code Geass screenwriter. Other works as chief writer, mostly made with studios Sunrise and Bones, include Overman King Gainer, Kabaneri of the Iron Fortress and Mobile Suit Gundam: the Witch From Mercury.

[8] Yuriko Chiba (1967-). Animator, character designer. Planetes character designer, Code Geass main animator. A close collaborator of Gorô Taniguchi, she is one of the most famous female animators and designers in Japan. Her work is particularly praised for its realism and sense of detail.

[9] Gravity. 2013 movie, Esperanto Filmoj & Reality Media & Warner Bros. Heyday Films, dir. Alfonso Cuarón. Starring Sandra Bullock and George Clooney, this SF film follows an astronaut stranded in Earth orbit after her shuttle has been hit by space debris. Widely praised for its special effects, it garnered many awards, including the Best Director Academy Award.

[10] The Orbital Children. 2022 TV series, Production +h., dir. Mitsuo Iso. Mitsuo Iso’s second directorial effort, years after his debut series Dennô Coil. An ambitious near-future story following a group of teenagers having to survive in a space station on their own.

[11] CLAMP. A collective of 4 female artists formed in 1987 and still active today. Notable works include RG Veda, X/1999, Cardcaptor Sakura… They provided the original character designs for Code Geass.

[12] Takahiro Kimura (1964-2023). Animator, character designer. Code Geass character designer. One of the most important character designers working with Sunrise in the late 1990s and early 2000s with works such as King of Braves GaoGaiGar. Kimura’s designs are particularly well-known for their sex-appeal.

[13] Kenji Teraoka (1962-). Designer. Code Geass concept designer and mechanical designer. Mechanical designer most famous for his collaborations with studios Bee Train (Noir), Production IG (Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex series) and Sunrise (Gundam 00, Mobile Suit Gundam: the Witch from Mercury)

[14] Reiko Iwasawa. Color designer. Code Geass color designer.

[15] Legend of the Galactic Heroes. 1988-1997 OVA series, studio OVAK-Factory & Kitty Film Mitaka Studio, dir. Noboru Ishiguro. An adaptation of Yoshiki Tanaka’s famous space opera novel series, the first animated adaptation is well-known for being the longest OVA series ever made. Still famous to this day, it is particularly appreciated for its depiction of space warfare and strategy.

[16] Spiderman: Into the Spider-Verse. 2018 movie, Sony Pictures Animation, dir. Bob Perischetti, Peter Ramsey, Rodney Rothman. One of the most important animated films of the last decade, it has had a revolutionary impact on US animation thanks to its blend of 2D and 3D animation techniques.

[17] Arcane. 2021 web series, Fortiche, dir. Pascal Charrue & Arnaud Delord. Set in the universe of the League of Legends video game, Arcane is considered to be one of the best animated series of the last few years. Like Spiderman: Into the Spider-Verse, it is remarkable for its blend of 2D and 3D animation.

[18] Wolfwalkers. 2020 movie, Cartoon Saloon, dir. Tom Moore & Ross Stewart. The third and final installment in Tom Moore’s “Irish folklore trilogy”, it follows a girl and a werewolf befriending each other.

[19] Long Way North. 2015 movie, Sacrebleu Productions, dir. Rémi Chayé. The first feature by French director Rémi Chayé, about a Russian teenager traveling to the North pole in the XIXth century.

[20] The Legend of Hei. 2019 movie, Joy Pictures, dir. MTJJ. Chinese animated film, prequel to the Flash animated series The Legend of Luo Xiaohei. It represented the breakthrough of Chinese 2D animation on the Chinese, Japanese and American markets.

[21] [21] Charles-Émile Reynaud, Émile Cohl. French directors, pioneers of animation in the late XIXth century and early XXth century.

All our gratitude goes to Mr. Taniguchi for his time and kindness, as well as to Mr. Hisayuki Tabata and Ms. Yuriko Chiba for making it possible.

Interview by Matteo Watzky and Dimitri Seraki.

Assistance by Ludovic Joyet.

Transcript by Eileen.

Translation by Eileen and Matteo Watzky.

Introduction and notes by Matteo Watzky.

This article would not have been possible without the help of our patrons! If you like what you read, please support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Oshi no Ko & (Mis)Communication – Short Interview with Aka Akasaka and Mengo Yokoyari

The Oshi no Ko manga, which recently ended its publication, was created through the association of two successful authors, Aka Akasaka, mangaka of the hit love comedy Kaguya-sama: Love Is War, and Mengo Yokoyari, creator of Scum's Wish. During their visit at the...

Ideon is the Ego’s death – Yoshiyuki Tomino Interview [Niigata International Animation Film Festival 2024]

Yoshiyuki Tomino is, without any doubt, one of the most famous and important directors in anime history. Not just one of the creators of Gundam, he is an incredibly prolific creator whose work impacted both robot anime and science-fiction in general. It was during...

“Film festivals are about meetings and discoveries” – Interview with Tarô Maki, Niigata International Animation Film Festival General Producer

As the representative director of planning company Genco, Tarô Maki has been a major figure in the Japanese animation industry for decades. This is due in no part to his role as a producer on some of anime’s greatest successes, notably in the theaters, with films...

In the paragraph where Taniguchi talks about Kimura’s hypothetical intuition in designing Harry Potter characters, “Jenny Wiesley” should be “Ginny Weasley.”

Thank you for pointing it out. It’s been corrected 🙂