Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And if you gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil pg.146

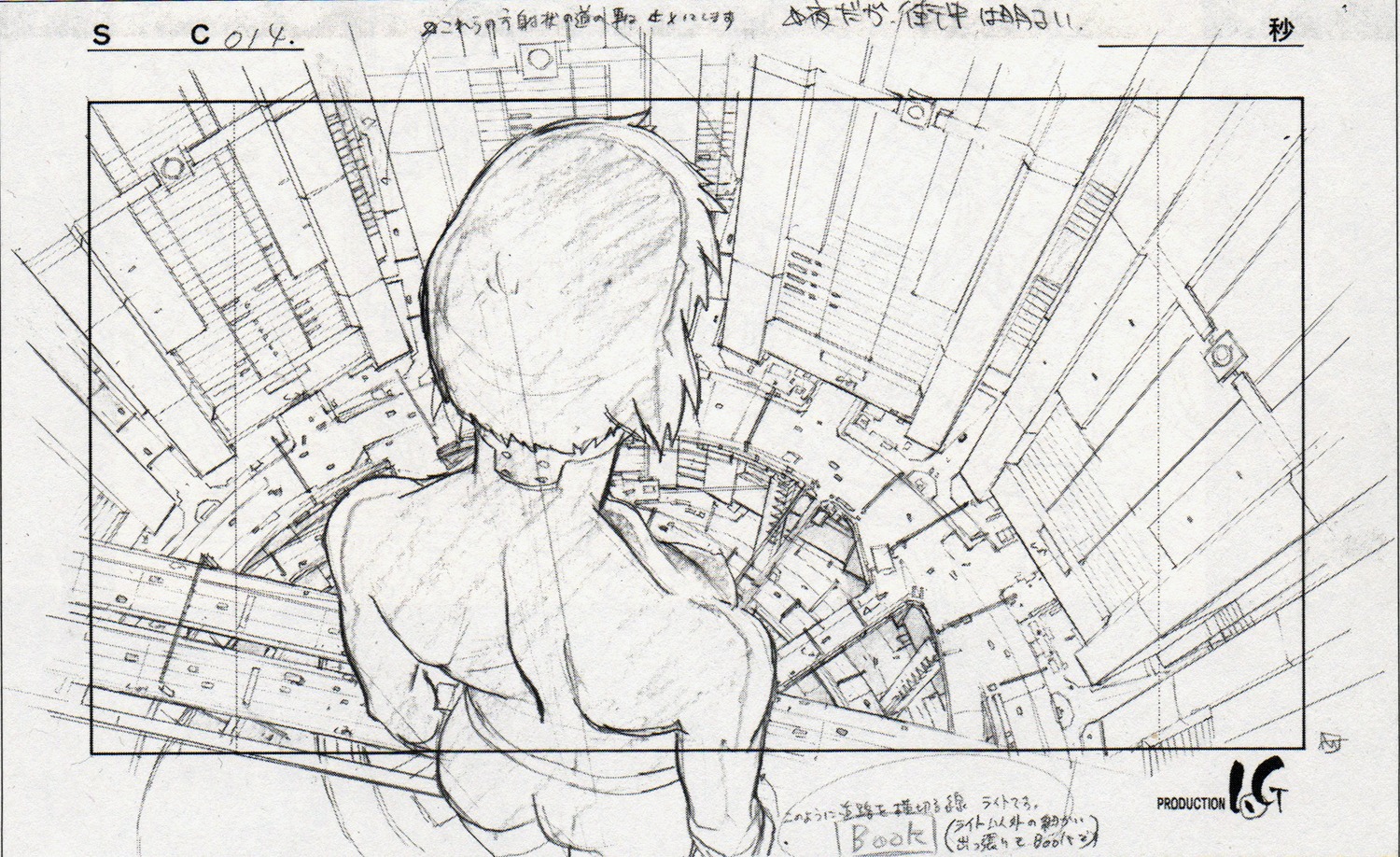

It’s an eerie feeling whenever you see the evil of others inside yourself. And that’s really, what Ghost in the Shell is all about. It’s villains are not so much individuals of absolute evil, but more a single face among the sea of people in the tide of a social issue. These villains emerge not as maleficent forces but more as side effects of the cultural environment they inhabit. That’s a big deal. Because what it does is makes a statement that what we call ‘evil’ is not a force that seeks to harm and disrupt from the outside, but much rather a byproduct of who we are. And that’s really the message of Ghost in the Shell in all of it’s incarnations. To show us just how inhuman we are at our most human, and just how human we can be when we resemble something not human.Key to this ideology is the mantra, ‘your body does not define you’.

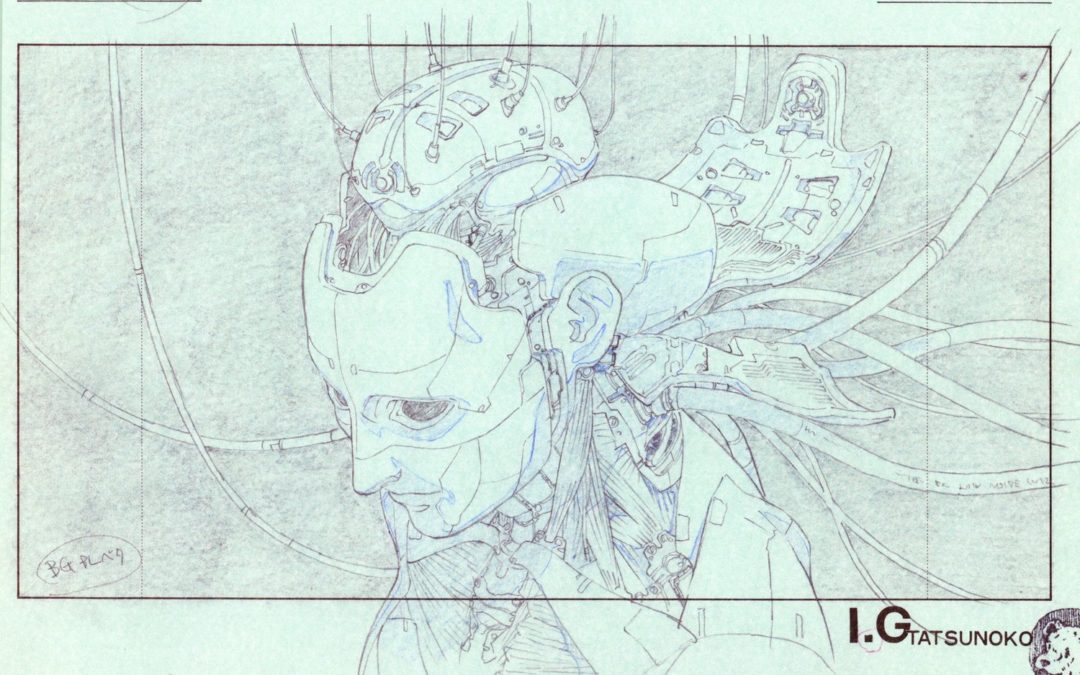

Though the methods are still restricted (by cost, societal standing, and every other facet of late capitalism), the means to transcend the human body is available to most everyone in Masamune Shirow’s world. Even some of the indigent in the series have cyberbrains, allowing the human consciousness to dive into cyberspace, effectively existing outside of a body, experiencing sensations freed from the shackles of the flesh. This begs a vary interesting question though: once separated from your body, what gives you your sense of self?

Capitalism is about commonality; the lowest common denominator. Complete the most amount of things for the least amount of expense. As automation becomes more and more capable of replacing human labor (a problem we actually face in our reality) the value of human capitol disappears. Human efforts become devalued, replaced by the precision and consistency of the mechanical. Slowly, we see the value of being human cast aside, forgotten.

GitS answers this problem by fusing machine with man, bringing to mind the old adage of ‘if you can’t beat them, join them,‘ and assigns a value to the unique human body. This proposes this thought – how much is your body worth? Being assigned a monetary value, bodies are quite literally objectified and termed “shells”. This is where GitS shines the brightest; introducing the transhumanist notion that mankind can develop past their natural limitations, so much so that it challenges our current understanding of being human.

Case and example, the character Togusa. Throughout the multiple series, he is generally referred to as a natural; he has no major cybernetic augmentations. Augmenting and altering the human body is a common enough practice that someone having no enhancements is odd, even if it is their choice. Togusa is mocked and teased by his psychical superiors for choosing to remain low-tech and organic, but they respect his decision at the end of the day because that’s who he is. As the ‘most human’, he functions as a sort of audience surrogate, as well as a yardstick for just how amazingly powerful (read: inhuman) his team members are.

Togusa is painted as the everyman we can relate to in this brave new world of technology. He chooses to stay behind the times because it’s what he feels comfortable with (even going so far as to carry a revolver as his firearm), but also because that’s what we as flesh and blood viewers can understand. But even Togusa has a cyber brain. He is the bridge, the missing link, between what humans are now, and what they will be… at least according to Ghost in the Shell.

But through Togusa’s interactions, we see he does not behave any differently than the rest of the characters. Thus proving the point that no matter how cyberized people get, the human form remains. This seems like an obvious decision when you consider character designs and limitations of animation, but from an in-cannon perspective, this conclusion is not so clear. There’s no utilitarian function served by the human body that couldn’t be better served by another design. In fact, it’s stated multiple times across multiple incarnations of the series, that people can either transfer their cyber brain from shell to shell. We saw this in the final act of the original film by Mamoru Oshii, with Project 2501, the Puppet Master, taking control of a spider tank to battle the Major. But still, people choose to take a human form, a form most familiar to them. This says a lot about what is important to being human. Even with all the money in the world, the human form is still considered a part of human identity.

At the same time and counter to this is irrefutable and tangible evidence of a soul. Dubbed a ‘ghost’ (hence the title of the series), who a person is, their personality, is digitized, allowing for transference of consciousness between shells without moving the cyberbrain. The idea that the mind and body are separate is an obvious dichotomy, but GitS expands it. Despite being separated, there are some things that the mind keeps with it as an innate identity regardless of physical form. This idea circles back to the body as an object; that your body is not ‘your body‘ but ‘a body.‘

This ability to transfer between bodies presents interesting ideas about gender and sexuality identities as well. In GitS, swapping bodies is normal and easy, just as it should be. What doesn’t change is the ghost, the actual person. In this light, the future, through science, has become far more progressive. Barriers and labels (such as transgender and sexual orientation) start to mean nothing because the body does not define the person unless they let it (a la, Togusa’s case). Instead of psychical elements, choices start to define a person. The body becomes an outward manifestation of that choice.

Think of tattoos, piercings, or similar body alterations in modern culture – it’s about what feels comfortable, familiar. Even when nearly all possible restrictions of humanity are removed, people still have a sense of what feels ‘correct’ to their individual – what they identify with. Ghost in the Shell frees some (but not all) from the absolute necessity of biological function. Brains still need glucose and other matter to survive, but someone like Major Kusanagi doesn’t need to feel hungry. They don’t have to feel cold or hot. They don’t really have to feel much of anything. The human body and all of its functions become opt-in rather than mandatory. You can have any body you choose, but most vie for a human form. You could change from your male body to a female one, or vice versa, but most people stay with what feels comfortable.

This concept is really a basic version of gender performativity, or the idea that gender is determined by repetition of actions in a society. It’s gender as a social construct. The expression of masculine and/or feminine traits is not something that is designated by the character’s shell, but by their choice/decision to stay within that shell. Oshii displayed this with the Puppet Master, having a male voice inside a female body, then again with the conversation between Bato and the Major when he suggested she upgrade to a more physically capable shell. When men and women are 100% biologically equal, old fashioned gender roles start to erode and are replaced with expression. In ARISE, Makoto inhabits a masculine body as part of a mission, but she is still a woman. So, across multiple iterations, as she sees it, there’s no need for her to change. A feminine body is where she belongs, and no amount of increased muscle power will alter that. Batou’s opinion, no matter how logical, is irrelevant.

It’s very easy to imagine a future in which humans have transcended want and need, post-technological singularity where all thought is digitized and we are freed from the prison of the flesh. In the future, we may elevate ourselves above petty distractions, and the average human could become some paragon of asceticism. Ascended, wise. The apotheosis of a Buddhist monk in the West. But it turns out that in a world where humans can be psychically perfect, there are still numerous problems that exist – and those problems are very human.

Humans are naturally social. We desire for connection, intimacy, and being able to feel exactly what someone else is feeling. But there is no way, in our current being, that we can achieve this. Feeling another’s sensations as your own, connecting your thoughts to another, is the final barrier. Breaking that, would finally allow us to understand each other completely and make peace. Yet, in Ghost in the Shell, it does not. Humans remain human. As close to self-actualization as we get, as near to mutual understanding as we are, humans are all different. We are imperfect.

All these issues of identity require us to be more identifiable. In the postmodern soup of existence, definition and labels become more important. If I cannot identify myself, then how do I begin to identify the world around me? Even when you can outwardly express exactly who you think you are, there is still doubt when staring into the void of one’s self. And when you stare into the abyss, sooner or later, it stares back at you. Returning to our opening thought— What we call ‘evil’ is a byproduct of our failing in being human. ‘Evil’ is the space in between people; not understanding who the stranger is, or who we are.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Benoît Chieux, a career in French animation [Carrefour du Cinéma d’Animation 2023]

Aside from the world-famous Annecy Festival, many smaller animation-related events take place in France over the years. One of the most interesting ones is the Carrefour du Cinéma d’Animation (Crossroads of Animation Film), held in Paris in late November. In 2023,...

Directing Mushishi and other spiraling stories – Hiroshi Nagahama and Uki Satake [Panels at Japan Expo Orléans 2023]

Last October, director Hiroshi Nagahama (Mushishi, The Reflection) and voice actress Uki Satake (QT in Space Dandy) were invited to Japan Expo Orléans, an event of a much smaller scale than the main event they organized in Paris. I was offered to host two of his...

Akira stories – Katsuhiro Otomo and Hiroyuki Kitakubo talk at Niigata International Animation Film Festival 2023

Among the many events taking place during the first Niigata International Animation Film Festival was a Katsuhiro Otomo retrospective, held to celebrate the 45th anniversary of Akira and to accompany the release of Otomo’s Complete Works. All of Otomo’s animated...

Recent Comments