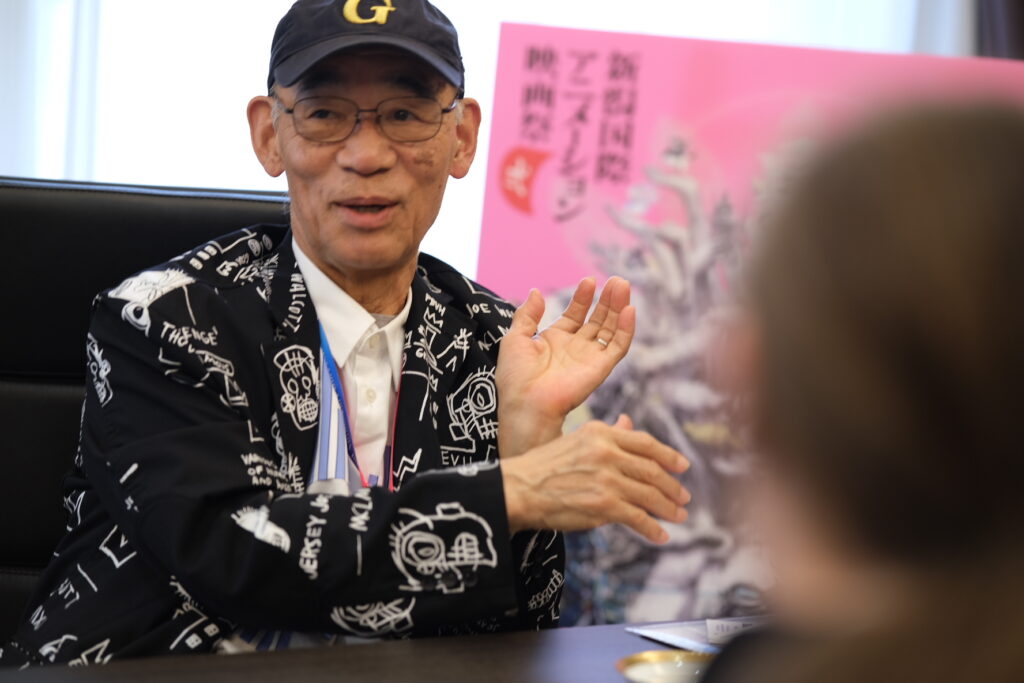

During our time at the second edition of the Niigata International Animation Film Festival, we had many encounters and reunions. Among those was Mr. Tadashi Sûdo, whom we were used to seeing at the Annecy Animation Festival. While maybe not well-known to the Western audience, Mr. Sûdo is a major figure in Japanese animation journalism, notably for his website Animation Business, which reports most news related to economic developments within the anime industry.

Since last year, Mr. Sûdo has also been one of the key members of the Niigata Animation Festival as its “program director”. He is the one to decide on the festival’s contents and the one who makes possible its diverse lineup. During our conversation, we discussed his view of current trends in the anime industry, the increasing globalization of anime, and where the Niigata festival situates itself in the midst of these developments.

This interview is brought to you through a partnership with Animeland, France’s first anime and manga magazine

This article would not have been possible without the help of our patrons!

If you like what you read, please support us on Ko-Fi! Get extra perks by subscribing to a monthly membership!

This interview is also available in Japanese. 日本語版はこちらです。

“Talking in global terms, there’s definitely a big anime boom going on”

First, I’d like to talk not with Tadashi Sûdo, the program director of the Niigata International Animation Film Festival, but with Tadashi Sûdo from the website Animation Business. Could you tell us how you became an animation journalist?

Tadashi Sûdo: I used to work at a brokerage firm, and I didn’t really like what I was doing there, so I wondered what to do with my life. It was at that time that I enrolled in a graduate school and, after graduation, wanted to get involved in actual business. So I started an animation business site – or rather, an information site, called Anime! Anime! It’s that way that I got into this world.

Right now, as you’re managing the festival, you have to know not just about commercial Japanese animation but also Japanese independent animation and foreign animation. How did you come to be interested in things besides Japanese anime?

Tadashi Sûdo: Well, there are, of course, many great things made in Japan, but they tend to all follow the same trends – for instance, the style of the drawings tends to always be a bit similar. So there comes a point when you want to see more diverse things: I’d say it started with a desire to discover new, more diverse worlds.

I see. Coming back to what you were saying earlier, why did you want to look at anime from a business perspective?

Tadashi Sûdo: As I said, I’d say it’s because of my background – I’ve always liked economics and numbers. So whenever an anime became a hit, I asked myself: why did that anime become a successful project, or when I met people from overseas asking if such work really made money in Japan – that’s how I came to be interested in those things. I started writing, and as things went, all the articles I penned talked about business, so, at some point, the only offers I received were about such subjects. At first, I only wanted to be a normal journalist, but for some reason, now I’ve become a sort of business specialist.

You just said you asked yourself why some anime became hits. From your perspective today, why has Japanese animation become so big worldwide?

Tadashi Sûdo: That’s a difficult question, but it’s an interesting topic. Animation has long been a Japanese product – in the 1970s and 1980s, there were already some Japanese productions popular overseas. But it definitely feels like since the 2010s, the popularity of Japanese anime overseas has dramatically increased. One of the key factors would, of course, be streaming services.

So would you say we’re in the midst of a new anime boom?

Tadashi Sûdo: Talking in global terms, there’s definitely a big boom going on. Even within Japan, there have always been anime fans, but now it’s spreading to the general public. Nowadays, it’s like animated films breaking box-office records keep coming out. Animation was popular before, but it’s really becoming something anyone would watch. I can’t tell if this is a ‘boom’ or something that won’t change, but what’s certain is that anime has become much bigger than it used to be.

“The anime style itself has spread all over the world, and it’s clearly not just Japanese anymore”

A global boom is going on, but looking at the industry in Japan, there are a lot of foreign animators coming, as well as a lot of money from overseas. With this in mind, it feels like “Japanese anime” isn’t just Japanese anymore, but more like a brand. What do you think?

Tadashi Sûdo: I think that’s something that can’t be stopped anymore. I suppose that, in earlier times, “anime” didn’t mean a specific “anime style” but just a Japanese production. Nowadays, however, when you look at works like RWBY – though that’s already a bit old now – or Arcane, there are a lot of anime-like points. In that sense, the anime style itself has spread all over the world, and it’s clearly not just Japanese anymore.

I suppose there are such works like this being screened at the Niigata festival.

Tadashi Sûdo: That’s right. In competition, we have the Thai movie Mantra Warrior: The Legend of the Eight Moons, for instance – though the director initially worked in Blue Sky studios, so they’re working with technologies and methods borrowed from the US. But, when you watch the movie, it looks like Japanese anime. It’s about Thai mythology, so I’d say it’s new – or rather, it makes me feel like, “that’s how things will go from now on”. European sensibilities, American sensibilities, Japanese sensibilities are becoming increasingly hybrid, and will be borrowed by other countries who will, in turn, add some things of their own.

So, I just said that anime’s global turn can’t be stopped, but I’d actually say there have been three steps to that.

The first is the market expanding overseas. Until now, Japanese animation was exported overseas, but it was in restricted areas – the US, Canada, China, Korea and Taiwan, and then Western Europe. But now it’s expanded to Latin America and, the Middle-East, Southern Asia: it’s become a worldwide phenomenon.

Then, there’s the creators who become global. Right now, there’s a lack of human resources and it’s becoming difficult to produce anime entirely in Japan. Of course, in-betweens or such have been subcontracted to China or Korea before, but what’s going on today is different: animators, animation directors, even directors come to Japan now – or some don’t even need to come from Japan to work on Japanese productions. In that sense, the staff is becoming global. This is only getting stronger, so the time when anime is made only by Japanese people has come to its end.

Finally, and very importantly, is the origin of the money. Things aren’t simple with Netflix or Crunchyroll, but companies from China or Saudi Arabia are starting to invest in anime, so investment policies are also becoming global.

In sum, there are different layers to it: the planning and financing going global, the creators going global, and the market going global. And I don’t think this movement can be changed.

I see, thank you. Here’s the final question before we move to the festival itself: looking at the history of anime journalism, during the anime boom you had Animage, now you could say you have Animestyle, basically magazines looking at anime from an artistic angle. But there’s never really been a business-centered approach like yours before, right? Shouldn’t the two be complementary?

Tadashi Sûdo: The truth is, there aren’t that many people interested in business information. Fans don’t really care.

But there are people interested in it, aren’t there?

Tadashi Sûdo: Really? (laughs)

For instance I’m thinking of Yumiko Watanabe. She’s a journalist, but she also released books about anime business at the Comiket – some people must have bought it, right?

Tadashi Sûdo: That’s true. Ms. Watanabe used to be a voice actress, so that might be how she got interested in all this. But since there wasn’t a lot of interest in it, there was no place to write about it either. But it’s become easier now, so she’s found places to publish her work as well.

“Animation festivals all over the world tend to privilege auteurs”

I see, thank you. Now, let’s talk about the festival. In terms of animation festivals in Japan, the existing ones like the Hiroshima festival or the New Chitose Airport festival were more focused on independent animation, right? So how was a more industry-focused one like Niigata created?

Tadashi Sûdo: I wouldn’t say it’s focused on the industry.

I meant that, compared to Hiroshima or Chitose, it’s not only independent works, right?

Tadashi Sûdo: Actually, Hiroshima has changed directors, so they’re also trying to broaden their focus. But the truth is that animation festivals all over the world tend to privilege auteurs, and so they’re often places to feature works made by a single individual or a small team. The reason for that is that TV anime is broadcast on television already, while features are distributed in theaters. But for a long time, there was no place for independent animators to distribute their shorts. That’s why festivals developed, but now, with the Internet, they can be spread easily, meaning that it’s become harder to justify festivals just for shorts.

So in my mind, what we’re doing here in Niigata is to not discriminate between independent artists and commercial artists but instead to line them up together. It seems people often believe we’re a festival just dedicated to commercial or entertainment works, but the truth is that the Niigata festival aims to include everything, from art to entertainment.

Related to that, it feels like Niigata is trying to become the next Annecy – or, well, that might be a bit too strong a way to put it, but there’s definitely a connection, or an influence from Annecy, right?

Tadashi Sûdo: There is, without any doubt. After all, Annecy has become so big for the world of animation that it’s become the center of everything. It’s the standard for everybody. And I think that’s good! A lot of wonderful information is being shared and a lot of works are being announced… But I’d like to show different things – to show that it doesn’t all have to be like in Annecy. In that sense, you could say we’re trying to do in Asia what Annecy is doing in Europe.

That’s also because I think the way we see things in Europe and Asia is different. As much as things are becoming global, there was something I was a bit frustrated with when surveying Annecy’s official selection: works with political themes are the ones which always end up getting prizes. More specifically, it seems that gender issues are the kind of theme that makes it easier to enter the official selection. And the thing is that works made in Asia – not just Japan – aren’t really in touch with such themes.

Another example is our guest for this year, Yoshiyuki Tomino: he’s very popular, and that has attracted a lot of attention and brought a lot of people to the festival. But that’s not why I wanted to invite him: I wanted to show that there can be auteurs even in robot anime franchises. You couldn’t screen a robot anime in any festival, Annecy or elsewhere. But it’s precisely what makes Niigata what it is: it’s the only festival where Yoshiyuki Tomino’s Char’s Counterattack can be showcased as the work of an auteur. Basically, art animation is also entertainment in a way, and you can find auteurs in commercial animation. That’s why I believe it’s necessary to showcase both together.

“I believe we had to do it in Niigata”

You mentioned Asia and, to ask this directly, why was Niigata chosen?

Tadashi Sûdo: That’s what everybody asks. (laughs)

I mean, I’m glad it’s not Tokyo, but out of all the cities in Japan, why Niigata?

Tadashi Sûdo: One of the reasons is the presence of the Kaishi Professional University in Niigata, which has an anime-manga course. More generally, the city of Niigata has been investing a lot in manga and animation these past few years. So they were thinking of ways to liven up the city even more through animation, and that’s when Kenzô Horikoshi, the chief of the executive committee, made multiple suggestions, among which holding an animation festival.

Once we tried it out, we realized Niigata was the perfect location! It’s neither too close nor too far from Tokyo. There are events like the Tokyo International Film Festival or Anime Japan going on, of course, but the truth is that it’s too difficult to organize such events in the capital.

I see. And, well, I agree that while the TIFF is great, it doesn’t really feel like a true “film festival”.

Tadashi Sûdo: Indeed.

I mean, festivals are places for everyone to meet, for artists, journalists and normal people to mix up. I didn’t really feel that when I went to the TIFF.

Tadashi Sûdo: I think that’s why you shouldn’t do festivals in big cities – not just Tokyo, but New York, Paris or London…

I agree. And that’s precisely what makes Annecy so fun.

Tadashi Sudô: Indeed, you should do such events in smaller cities like Cannes or Venice. And Niigata is just around that size.

But another important thing to consider when organizing a festival is, are there enough theaters and hotels and everything? Also, Niigata’s food is tasty. Considering all of this, the question rather was: why hasn’t Niigata profited from all of it to hold more international conferences or events in the past? Personally, I believe we had to do it here.

Changing the subject, how did you come to become involved in the Niigata festival?

Tadashi Sûdo: It was thanks to Mr. Horikoshi, whom I just mentioned. As I said, he was thinking about doing something related to animation in Niigata and came up with three proposals. However, he’s originally a live-action producer, so he isn’t that knowledgeable about animation. That’s why he turned to Tarô Maki from Genco for help – since Mr. Maki produces both animation and live-action. After they talked, they turned to me for some more assistance.

At that point, I wasn’t supposed to act as program director or anything: they just asked me whether I thought it could work out. And since I didn’t think I’d be involved in the management, I got really enthusiastic and told them it was a great idea, that it would work out really well. But as things advanced, they needed both a program and a festival director – now, Shin’ichirô Inoue is the one handling that task. Anyways, they needed people, and as we were discussing potential candidates, they asked me to do it.

You weren’t involved in any festivals beforehand, is that right?

Tadashi Sûdo: I’ve been going to Annecy for a while.

I meant, involved as a staff member.

Tadashi Sûdo: Ah, that’s right, I hadn’t.

So could you explain in simple terms what being a “program director” is about?

Tadashi Sûdo: Basically, I’m the one deciding on what films I want to select, what kind of special events I want to see happen. For instance, both last year and this year, there have been retrospectives: I was the one to decide on Katsuhiro Otomo last year and Isao Takahata this year. There’s also the ‘Trends of the World’ category – I consider what’s trending right now, and I decide on what films I think must be shown in Japan, and decide on the themes and films.

How do you manage to select films that haven’t come out in Japan yet?

Tadashi Sûdo: Well, I go to Annecy, and when there’s a film I like, I enquire about it and start negotiations. For Japanese works, I try to see with the people holding the rights, whether they’d let us screen the film… It doesn’t always work out.

This year, one of the big events was the screening of Masaaki Yuasa’s shorts. I mean, A Slime’s Adventures hadn’t been screened in over 20 years! We were only supposed to show 4 shorts at first, but when I asked Yuasa to make a talk, he said that there were some more that hadn’t been screened in forever and that he wanted to see. And well, if Yuasa himself asked for it, there was no way we’d get refused, so I started negotiations with the right holders to screen it.

What would you say has changed compared to last year?

Tadashi Sûdo: The feeling I get is that the number of people coming has clearly increased.

I also feel like the festival itself has become bigger. The venues are, even the press room is much bigger than last year.

Tadashi Sûdo: We’ve also gotten a lot more talks. But maybe there are too many this time…

That’s the same in every festival. (laughs)

Tadashi Sûdo: And it’s become really busy. (laughs) I always get emails coming! (laughs)

Thank you for your efforts. (laughs) Niigata’s an international festival, right. I feel like this year, you’re putting lots of efforts into bringing foreign visitors and journalists, but how do you make that work?

Tadashi Sûdo: I actually think that’s our weakest point so far. I feel like the PR for overseas wasn’t very well handled this time. For a festival to grow, you have to have people from overseas – they’ll stay the entire week, and they’re pretty passionate, so they’ll watch films from dawn till dusk. We have to bring such people. But right now, most guests are Japanese, and I think we’ll have to change that.

Besides that, if there’s anything you could change or improve on for next year, what would it be?

Tadashi Sûdo: I think I can go even further with the program. This year, the competition is really good, and we’ve received lots of entries for it, so we had to be very careful in selecting them. Also, last year, we screened a lot of films that had already come out in Japan. But the point of the ‘Trends of the world’ category is to show films that haven’t come out yet, and we’ve managed to do it to some extent – but we can do more.

And, finally, I’d like us to receive more people from overseas. But it doesn’t have to be the US or Europe right now. The Niigata International Airport has direct connections with Seoul, Beijing, Shanghai and Taipei, and it takes just 1 or 2 hours by plane. So I’d be very glad if the people from there would come.

Interview by Matteo Watzky & Ilyes Rahmani Martinez (Animeland)

Transcript by Antoine Jobard.

Translation by Matteo Watzky.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Oshi no Ko & (Mis)Communication – Short Interview with Aka Akasaka and Mengo Yokoyari

The Oshi no Ko manga, which recently ended its publication, was created through the association of two successful authors, Aka Akasaka, mangaka of the hit love comedy Kaguya-sama: Love Is War, and Mengo Yokoyari, creator of Scum's Wish. During their visit at the...

Ideon is the Ego’s death – Yoshiyuki Tomino Interview [Niigata International Animation Film Festival 2024]

Yoshiyuki Tomino is, without any doubt, one of the most famous and important directors in anime history. Not just one of the creators of Gundam, he is an incredibly prolific creator whose work impacted both robot anime and science-fiction in general. It was during...

“Film festivals are about meetings and discoveries” – Interview with Tarô Maki, Niigata International Animation Film Festival General Producer

As the representative director of planning company Genco, Tarô Maki has been a major figure in the Japanese animation industry for decades. This is due in no part to his role as a producer on some of anime’s greatest successes, notably in the theaters, with films...

Recent Comments