Shin’ya Ohira needs no introduction: with his immediately recognizable style, which emphasizes irregular linework and deformation, he is one of the most unique animators in the world. But Ohira’s style and career do not just amount to the deformations he is famous for today.

He entered the animation industry at just 18, joining studio Pierrot and specializing in mecha animation as one of the most ardent followers of Masahito Yamashita. But he soon moved on to character animation and, following his work on Akira, worked with the greatest animators of the realist generation: Satoru Utsunomiya, Mitsuo Iso, Osamu Tanabe… He was one of the most radical members of the group, working on experimental works such as The Antique Shop or the Junkers: Come Here pilot film. This experimental tendency naturally led him to work with then-unknown Masaaki Yuasa on one of the most revolutionary episodes in anime history, Hakkenden: Shin-Sô #04. From that point on, he developed the idiosyncratic style we know today.

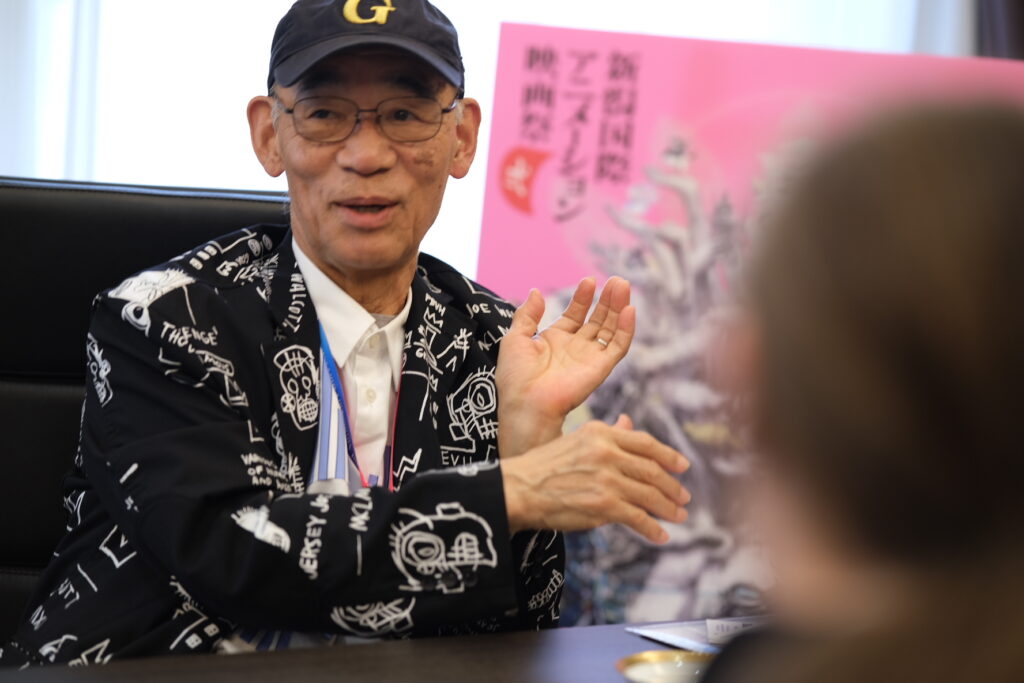

We had the opportunity of meeting Mr. Ohira as well as his friend Jun’ichi Takahashi at the Made In Asia convention, held in Brussels in September 2022. They had come to promote the activities and publications of their independent organization, Studio Break, which regularly publishes artbooks and flipbooks by its members and collaborators. This is where we started our conversation, but we could also discuss Ohira’s career as a whole – its past, present, and future.

This article is available in Japanese. 日本語版はこちら

This exclusive interview is provided to you for free. If you want to see more content like this, consider supporting us on Ko-Fi!

“I had the idea of making something about my own personal history”

Mr. Ohira, we’re very happy to have this opportunity to talk with you. How do you like Belgium?

Shin’ya Ohira: Thank you. I had the opportunity to eat and drink a lot, especially Belgian beer! (turns to Takahashi) We’ve drunk quite a lot already, right? I don’t know how many beers I’ve had (laughs). It’s a lot of fun.

Is this your first time in Europe?

Shin’ya Ohira: Yes, it is. I don’t really like taking the plane… (laughs)

Thank you for making the effort, then. But does that mean you won’t be back?

Shin’ya Ohira: I wonder… (laughs)

I hope you’ll come back! Mr. Ohira, your animation is already very famous, but people don’t really know about your organization, Studio Break. Can you or Mr. Takahashi tell us more about it?

Shin’ya Ohira: Well… When I went freelance, I started working together with a friend, and at the time, we thought it would be better to have a name or something. But it’s not a company, just a group with a collective name. And then, well, I don’t know if I should be telling you this, but when we don’t want to be credited on something, we use “Studio Break” as a sort of pen name.

Besides you, who are the other members?

Shin’ya Ohira: At first, only Atsushi Yano[1] and I. Then, Shinji Hashimoto[2] joined, Hokuto Sakiyama[3], and of course, Jun’ichi Takahashi. I think that’s pretty much it?

Mr. Takahashi, are you Break’s producer?

Interpreter: You’re playing a similar role, right?

Shin’ya Ohira: Yes, something like that. He takes care of the contracts and things like that. It’s not a company yet, but there’s a lot to handle…

Jun’ichi Takahashi: Maybe we could turn it into a company, eventually…

Studio Break is located in Chiba prefecture, is that right?

Jun’ichi Takahashi: Ah no, that’s where I am. We’re all scattered all over the country.

And Mr. Ohira, where are you based?

Shin’ya Ohira: Kitanagoya, in Aichi prefecture.

Is that where you live?

Shin’ya Ohira: Yes, that’s where my house is.

Mr. Ohira and Mr. Takahashi, can you tell us more about your relationship? How long have you known each other?

Jun’ichi Takahashi: We’re old friends. It’s been 27 or 28 years?

Shin’ya Ohira: That’s right.

I see. Now, Mr. Ohira, we’d like to ask about how you work. Usually, animators do the layout and first key animation, then there’s the second key animation, then the in-betweens… It seems impossible with your drawings. So what’s your method?

Shin’ya Ohira: Mmh, let’s see… Basically, I do all the animation myself most of the time. As for how I split the second key animation, it depends: I divide up the second key animation on the character parts, whereas I tend to do all of the stages of the animation on effects entirely by myself.

You’re still drawing on paper, or have you switched to digital?

Shin’ya Ohira: No, it’s all paper.

What pencils do you use?

Shin’ya Ohira: 6B and 10B.

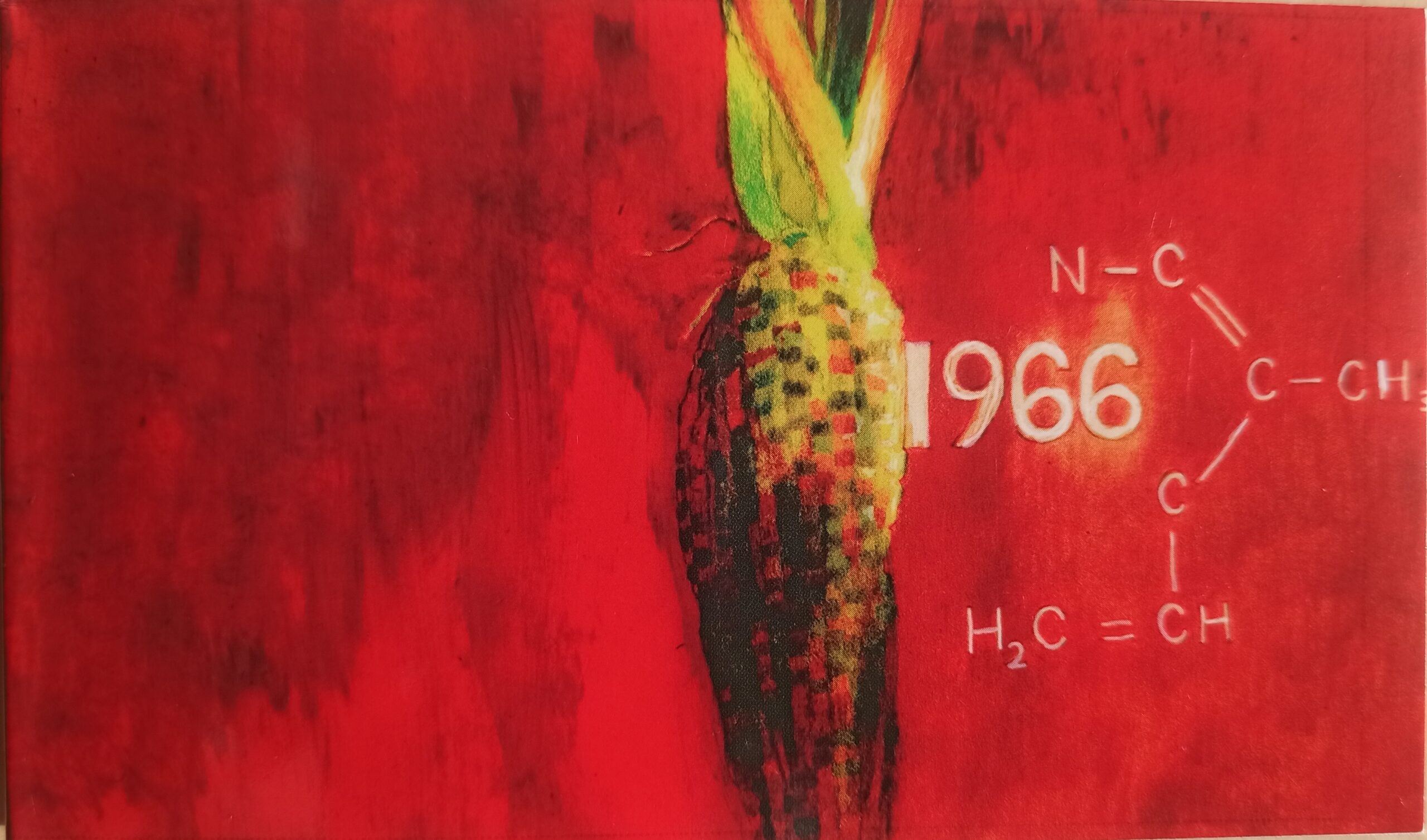

Among the flipbooks you brought to Belgium, there’s an autobiographical one titled 1966. Can you tell us more about the circumstances behind its creation?

Shin’ya Ohira: Well, we often publish flipbooks with Takahashi, but they are a hundred pages long, so you have to come up with a lot of drawings all by yourself. One day, I thought about what I should do, and rather than animation, I had the idea of making something about my own personal history. The drawings aren’t really connected, but each one represents an event in my life, and that’s how it happened.

You drew on the back of the Nagoya University paper, right? It’s still visible in the book.

Shin’ya Ohira: Wait, is that so? (laughs) It’s just that when I was making it, I was teaching there, so I just drew on the back of the sheets given by the university. You can still see the labels on the paper, huh? (laughs). Well, that’s how it is.

You don’t plan to turn this flipbook into a short film or something?

Jun’ichi Takahashi: You don’t, right?

Shin’ya Ohira: Well, the drawings don’t move, and it’s not a wedding ceremony film, you know! But it might be possible to make it into a film with something like a stroboscope to recreate that fuzzy feeling that memories have. But I’ve never considered it at all.

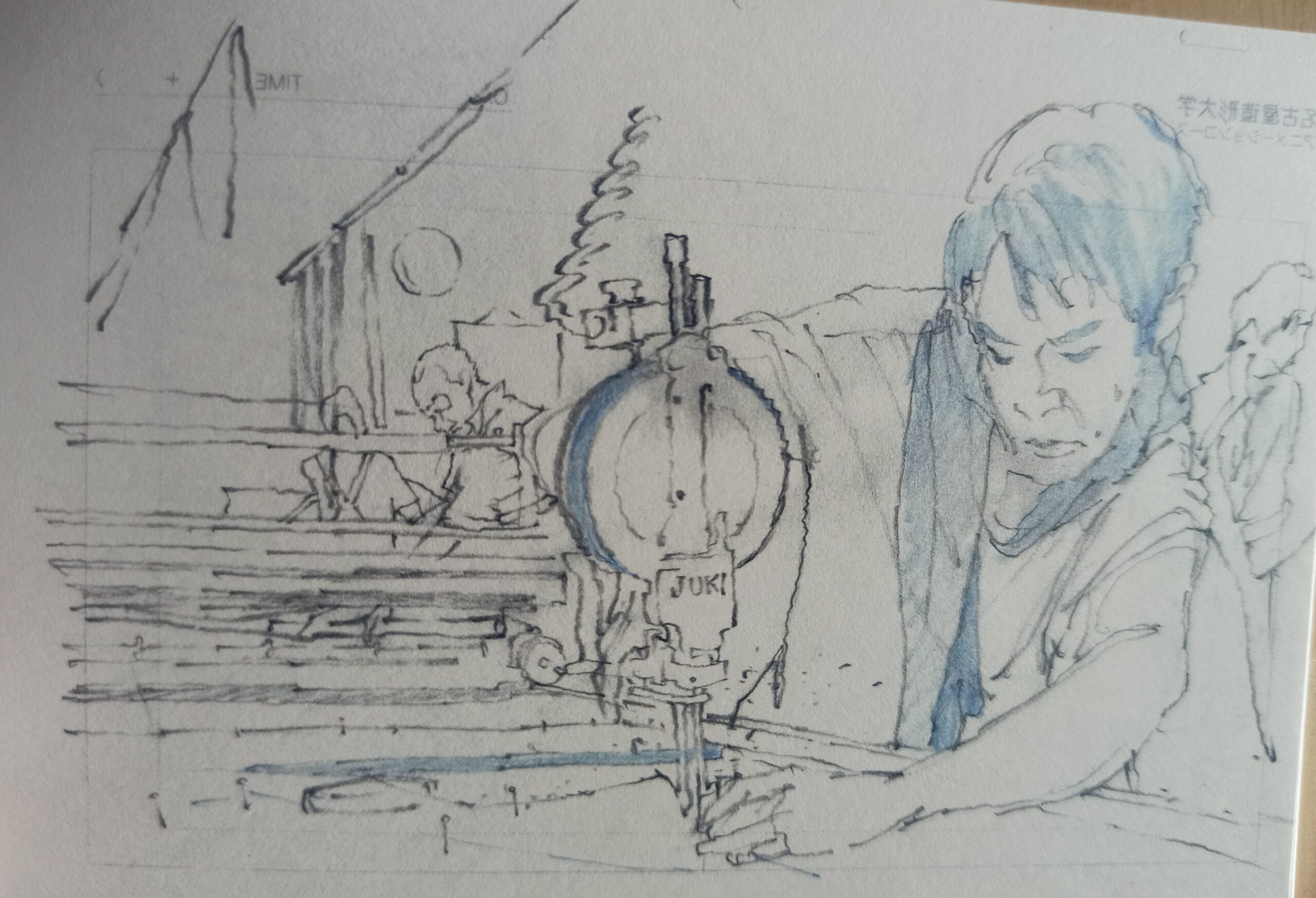

There’s one drawing in the flipbook I’m curious about. It’s the one where you’re drawn using a sewing machine. What does that reference? Was it a part-time job you took?

Shin’ya Ohira: No, not at all. My parents had a sewing factory, and I took up the business. You see, I took a long break from animation once.

But you came back to the industry. How did that happen?

Shin’ya Ohira: I believe we discussed it with Norimoto Tokura[4], and he convinced me to come back.

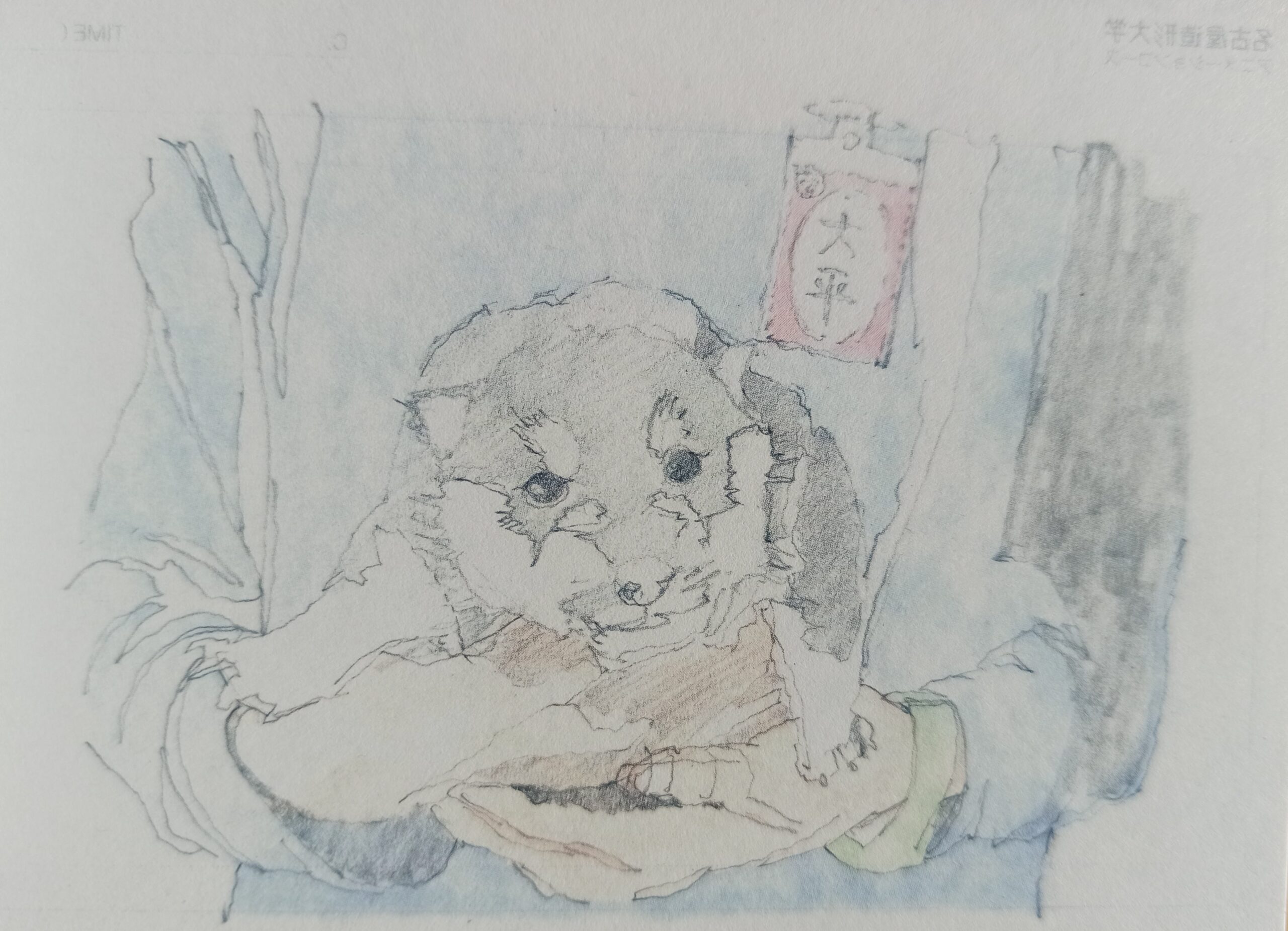

There’s a brief animated sequence at the end of the flipbook, which is very reminiscent of your short Wanwa the Doggy[5], and the last drawing is you with a dog. That’s a lot of dogs, isn’t it?

Shin’ya Ohira: Ah, that one is my dog. It’s a mameshiba named Suzuto. But he’s becoming an old guy now. (laughs)

“Yamashita’s animation is both sharp and sensual”

It’s well-known that you became an animator after discovering Masahito Yamashita’s[6] work on Urusei Yatsura[7]. What would you say is the appeal of Yamashita’s animation?

Shin’ya Ohira: Let’s see… (thinks) First, there’s the mood and dynamic action he inherited from Yoshinori Kanada[8]. But Yamashita has things that Kanada doesn’t, like physicality and details… It’s hard to express. Yamashita’s animation is both sharp and sensual. I really like that sort of fleshy mood, and I also love curved and irregular lines… Kanada used rulers, so it’s very sharp and straight, whereas Yamashita’s drawings are just curves, and he puts them together to create something very dense with details… (thinks) I think that’s what I like about him. That’s why I like Yamashita’s touch more than Kanada’s.

Since we’re on Urusei Yatsura, what movie is your favorite, Only You[9] or Beautiful Dreamer[10]?

Shin’ya Ohira: Only You, of course! (everybody laughs)

There’s a new Urusei Yatsura TV show coming out soon. Will you watch it?

Shin’ya Ohira: Well, you know… (laughs) The staff is totally different, and I’m not really into it for the story, so if Yamashita isn’t there, I don’t really intend to.

So, at first, you animated like Yamashita. But then you switched to something much more realistic, and your style has once again become completely different. Would you still describe yourself as a realist animator?

Shin’ya Ohira: Hmm… (thinks) Well, what I’ve wanted to do from the start is something visceral. But then I arranged this in a dynamic fashion characteristic of animation and made efforts in that direction so that the movement would remain animation-like. Right now, the way I see things is that I want to keep things visceral but also add the kind of deformations that are unique to animation.

I’d like to ask about the Junkers[11] pilot film. How did you come to work on the production?

Shin’ya Ohira: Junkers, huh… How did that happen… I can’t remember… What was the studio again?

Jun’ichi Takahashi: Triangle Staff.

Shin’ya Ohira: Ah, well, I think some producer from Triangle Staff had heard about me and contacted me for the job. And then… why did they think about me specifically to do the character designs and animation direction? I don’t think I’ve ever asked them about that, or I’ve probably forgotten. I’m sorry.

On the pilot, you worked with Manabu Ohashi[12]. Do you have any memories of him?

Shin’ya Ohira: Well, for me, he was like a master among masters, someone really impressive… I was afraid of just approaching him, but I was happy as well. It’s sad that he died so early. I really loved his style, especially on Robot Carnival[13]. He helped with the animation of the pilot, and his drawings were absolutely beautiful.

Back then, you also collaborated a lot with Mitsuo Iso[14]. How did you two meet?

Shin’ya Ohira: Mitsuo Iso… I think the first time I became aware of him was on Gundam… Was it 0080[15]?

Jun’ichi Takahashi: Yes, 0080.

Shin’ya Ohira: It’s there that I first saw his drawings, and I couldn’t believe that someone was doing such amazing things. But then, how did we first meet?

Jun’ichi Takahashi: Wasn’t it on Gosenzosama Banbanzai[16]?

Shin’ya Ohira: Ah yes, Gosenzo. It’s probably when I did key animation for Pierrot on Gosenzo. Mr. Iso also participated, and I think that must be where we met for the first time. Probably. And after that, he helped out with various things I did, like The Hakkenden.

You mentioned Gundam 0080. You did some pre-production materials, but you quickly left. Why is that?

Shin’ya Ohira: I think that I had another job at the same time. That must have been Gosenzo, I think?

Jun’ichi Takahashi: I believe it was.

Ohira: Gosenzo must have become my main activity, and so… how do I put this… well, the work on Gundam was pretty hard, so in the end, I left to focus on Gosenzo.

Jun’ichi Takahashi: It’s also that back then, the “robot boom” was coming to an end, right?

Shin’ya Ohira: That’s right. Rather than mecha, I wanted to draw characters and people. So that probably played as well.

Mr. Takahashi, how do you see Mr. Ohira and Mr. Iso’s relationship as artists? Sorry if that’s a bit of a difficult question…

Shin’ya Ohira: Our relationship as artists? What is that supposed to mean? (laughs)

Jun’ichi Takahashi: Well, at first, it was rather like they mutually encouraged each other. But it turned into a competition, and now they’re more like rivals, in my perspective.

And what would you have to say about Mr. Ohira and Masaaki Yuasa’s[17] relationship?

Jun’ichi Takahashi: The difference is that they’re friends. You know, at first, it was Ohira who invited Yuasa to work on Hakkenden: Shin Sô and made him famous. Then Ohira quit the industry, and after that, it was Yuasa who asked for Ohira’s help with the things he directed. That’s how things went. I think they’re also very compatible in terms of style.

“I want to go back to my roots”

Mr. Ohira, have you seen Inu-Oh[18]?

Shin’ya Ohira: Yes, I have. I went to the theater to see it.

You didn’t participate, right?

Shin’ya Ohira: No, I didn’t. I wanted to, but sadly I was too busy with another project.

We mentioned Nagoya University earlier. Did you make any disciples while you taught there?

Shin’ya Ohira: “Disciple” is a bit much! (laughs) There were dozens of students in my classes, you know…

You’ve always had difficulty fitting into the commercial animation industry, so wouldn’t you like to try an independent production, like a short film?

Shin’ya Ohira: Ah, of course, I’d like to! I’d love to make one.

Jun’ichi Takahashi: He’d also like to do something else than a short.

Shin’ya Ohira: I really want to; I always have.

Do you have anything planned?

Shin’ya Ohira: No, it hasn’t gone that far. Something small might happen soon, though. But I’d like to make something longer before I die. Actually, I want to try doing mecha again. Of course, not 3D, all by hand. Something like what we used to do in the 80s.

Won’t you do a remake of Birth[19]?

Shin’ya Ohira: (laughs) Yes, something like that! I want to go back to my roots, you see. At first, I really liked Kanada and Yamashita, but I was rejected for it, so I had to change. But with things as they are now, I’d like to return to how it was before. At least once, I’d like to do a long-form work with my own interpretation of Kanada and Yamashita’s styles, which I couldn’t do when I was 18 or 20. It doesn’t need a story; I’d rather do something like a documentary about this kind of art. I just want to draw something that keeps moving.

Is that project advanced?

Shin’ya Ohira: It’s still close to nothing. (laughs) But that’s why this short we discussed earlier may happen eventually.

Have you concluded anything with a studio already?

Shin’ya Ohira: Yes, but I really can’t tell any more.

Jun’ichi Takahashi: There’s the copyright issue to consider as well.

Shin’ya Ohira: We don’t even know if it will be approved yet. It’s not even in planning yet.

We’re looking forward to it anyway! Thank you very much for your time today.

Interview by Ludovic Joyet, Matteo Watzky and Dimitri Seraki.

Interpreting by Ludovic Joyet, transcript by Comrade Karin, translation and notes by Matteo Watzky.

All our thanks go to the staff of Made in Asia, especially Mr. Emile Vermote, and to Mr. Ohira and Mr. Takahashi for their time and kindness.

Notes

[1] Atsushi Yano (1964-). Animator. Shin’ya Ohira’s friend and mentor, he was one of Masahito Yamashita’s most ardent followers in the 1980’s. He has now retired from animation.

[2] Shinji Hashimoto (1967-). Animator, character designer. One of Shin’ya Ohira’s closest friends since the early 1990s, he was one of the major members of the realist school of animation. While his style is similar to Ohira’s in its use of deformation, Hashimoto is also famous for his adaptability to all kinds of styles and has been a regular presence in studio Ghibli’s works.

[3] Hokuto Sakiyama (1985-). Animator. A longtime fan of Shin’ya Ohira, some of his famous works include Star Driver, Ping Pong: The Animation, and Space Dandy 2.

[4] Norimoto Tokura (??). Animator. Specialized in effects animation, his notable works include Mobile Suit Gundam: Char’s Counterattack, Last Exile, Redline, and Jujutsu Kaisen.

[5] Wanwa the Doggy. 2008 short, studio 4°C dir. Shin’ya Ohira. Ohira’s contribution to the Genius Party Beyond anthology. It follows a young boy and his dog in a world full of colors and adventures.

[6] Masahito Yamashita (1961-). Animator. One of the most important artists in 1980’s animation, he became famous for his extremely stylized drawings and offbeat sense of timing. He was particularly influential in the field of effects and mecha animation.

[7] Urusei Yatsura. TV series, 1981-1986, studio Pierrot & studio Deen, dir. Mamoru Oshii & Kazuo Yamazaki. One of the most important TV anime series ever made, it had a major impact on an entire generation of artists. Notably, it is there that animators such as Masahito Yamashita, Katsuhiko Nishijima, and Yûji Moriyama became famous. A remake, produced by studio David Production, started airing in October 2022.

[8] Yoshinori Kanada (1952-2009). Animator. One of the most important artists in Japanese animation history, who revolutionized mecha, effects, and character animation. Sometimes nicknamed “the father of sakuga”, he was one of the first animators to be widely recognized for his unique style. He has spawned generations of students, from Masahito Yamashita to Hiroyuki Imaishi and Yoshimichi Kameda. Notable works include Invincible Super Man Zambot 3, Galaxy Express 999, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind…

[9] Urusei Yatsura: Only You. 1983 movie, studio Pierrot, dir. Mamoru Oshii. The first film of the Urusei Yatsura franchise, featuring mechanical animation direction by Masahito Yamashita.

[10] Urusei Yatsura: Beautiful Dreamer. 1984 movie, studio Pierrot, dir. Mamoru Oshii. The second film of the Urusei Yatsura franchise famous for its departure from the series formula and for its high-quality animation.

[11] Junkers Come Here. 1995 movie, Triangle Staff, dir. Jun’ichi Satô. A family drama uniting some of the most important members of the realist school, notably Mitsuo Iso and Osamu Tanabe. Shin’ya Ohira had been the character designer and animation director of the pilot film but was replaced by Kazuo Komatsubara on the actual movie for not respecting the schedule and budget (the pilot’s production is said to have lasted six months).

[12] Manabu Ohashi (1949-2022). Animator. A unique figure in anime history, always at the limit between commercial and indie creation. One of the earliest members of studio Madhouse, he is especially famous for his collaboration with directors Osamu Dezaki (Treasure Island, Ashita no Joe 2, Space Adventure Cobra) and Rintarô (Genma Taisen, The Blade of Kamui).

[13] Robot Carnival. 1987 anthology, APPP. An anthology of short animated films reuniting some of the most popular animators of the 1980s. Under his pseudonym Mao Lamdo, Manabu Ohashi contributed the poetic short Cloud.

[14] Mitsuo Iso (1966-). Animator, director. One of the most important animators in recent anime history, Iso was one of the major figures in the realist movement thanks to his incredibly lifelike work. He has since then moved on to direction with SF series such as Dennô Coil and Extraterrestrial Boys and Girls.

[15] Mobile Suit Gundam: War in the Pocket. 1989 OVA, studio Sunrise, dir. Fumihiko Takayama. Iso’s work on this OVA, especially the Antarctic base attack at the beginning of episode 1, is what made him famous among fellow animators and animation fans. The effects style Iso experimented with had a tremendous influence on 1990s and 2000s animation.

[16] Gosenzosama Banbanzai!. 1989 – 1990 OVA, studio Pierrot, dir. Mamoru Oshii. This OVA is one of the first great masterpieces of the realist school in the post-Akira landscape. Under the animation direction of Satoru Utsunomiya, the animators from Akira came into contact with different radical artists such as Mitsuo Iso and Shin’ya Ohira. They heralded a new era for animation where dynamic motion, deformation, and realism would no longer be opposites but complementary.

[17] Masaaki Yuasa (1965-). Animator, director. First an animator famous for his unique approach to movement, full of deformations, Yuasa became one of the most important directors of the 2000s with his works Mind Game, Kaiba, and Kemonozume. He then created his own studio, Science Saru, which notably experimented with new techniques such as Flash animation.

[18] Inu-Oh. 2022 movie, Science Saru, dir. Masaaki Yuasa. Yuasa’s latest film and his final work at Science Saru. It is a rock opera following two artists in medieval Japan.

[19] Birth. 1984 OVA, Kaname Production, dir. Shin’ya Sadamitsu. Featuring character designs and animation direction by Yoshinori Kanada, it is his and his student’s ultimate work. However, it is also heavily criticized for its complete lack of a story.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Oshi no Ko & (Mis)Communication – Short Interview with Aka Akasaka and Mengo Yokoyari

The Oshi no Ko manga, which recently ended its publication, was created through the association of two successful authors, Aka Akasaka, mangaka of the hit love comedy Kaguya-sama: Love Is War, and Mengo Yokoyari, creator of Scum's Wish. During their visit at the...

Ideon is the Ego’s death – Yoshiyuki Tomino Interview [Niigata International Animation Film Festival 2024]

Yoshiyuki Tomino is, without any doubt, one of the most famous and important directors in anime history. Not just one of the creators of Gundam, he is an incredibly prolific creator whose work impacted both robot anime and science-fiction in general. It was during...

“Film festivals are about meetings and discoveries” – Interview with Tarô Maki, Niigata International Animation Film Festival General Producer

As the representative director of planning company Genco, Tarô Maki has been a major figure in the Japanese animation industry for decades. This is due in no part to his role as a producer on some of anime’s greatest successes, notably in the theaters, with films...

Thank you very much for this interview!

I would like to clarify one point: is “1966” an animated flipbook, or are there mostly static images with a little animation at the end?

It’s the second! Half of it is just static images/illustrations, and the second half has got a flipbook animation “sequence”. Then it concludes on the dog drawing that’s shown.