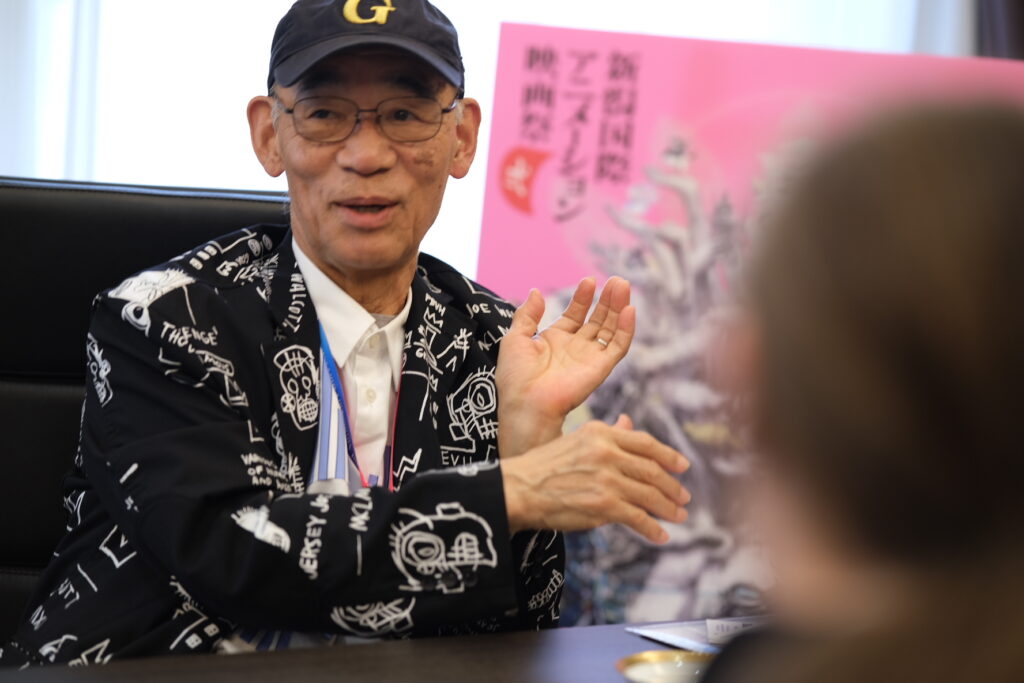

If you’ve watched any Sunrise anime from the 1980s or 1990s, chances are you’ve encountered Nobuyoshi Nishimura’s work or become aware of his name. As an animator and animation director, he was one of the core members of studio Dove, an outsourcing company mostly working with Sunrise, which had the particularity of being installed in Iwaki, Fukushima prefecture, instead of Tokyo.

Nishimura was an incredibly prolific artist and served as animator on some of Sunrise’s most iconic works: Dirty Pair, City Hunter, Patlabor… He was also a key part of “Heisei Gundam” shows, first as a member of the rotation of Victory Gundam and Gundam Wing and as character designer for After War Gundam X.

Although he was based outside of Tokyo, Nishimura is perhaps one of the best witnesses of how things went in Dove and Sunrise. Our meeting with him was a trip back in the 80s and 90s, which helped us understand the many secrets and methods of animation production and outsourcing.

This article would not have been possible without the help of our patrons! If you like what you read, please support us on Ko-Fi!

This interview is also available in Japanese. 日本語版はこちらです。

“That’s the story behind Dove’s creation”

First, I’d like to know how you entered studio Dove. Is that because you’re from Fukushima prefecture?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Not at all. I’m from Nagasaki! Dove was indeed in Iwaki, Fukushima, and in university, I was enrolled in the College of Engineering of Nihon University, which was in Koriyama, Fukushima. I was in the anime club, or what do you call it… Those manga or anime research circles. We were still students, but the seniors from the circle did a bit of training there.

I first visited Dove in the Fall of 1982, just when Macross[1] started airing: the first episode aired on a Sunday, and I went to Dove the Saturday just before that. I spent the night there. There was an empty desk, so the boss, Mr. Ihata, showed me around and let me see what they were working on back then: Xabungle and Dougram. That’s how I first came to Dove.

But thinking about it, maybe it wasn’t even called Dove yet back then… I believe it took the name “Studio Dove” only in the Spring of 1983.

Anyways, this was our first contact. And then, by the Spring of 1983, I had quit university and got back to Nagasaki to look for a job. I had to find something, but I had never really thought about it before… I wanted to do something related to animation, but there wasn’t anything in the area, so I was pretty lost and earned my bread with part-time jobs.

Then, one day, by complete chance, I saw Dove’s profile in Animage – back in those days, studios had job offers published there. Since I had gone there the year before, I figured I could get in more easily than any other place I didn’t know anything about, so I tried applying. After they got my application, Mr. Ihata called me, asking me how I planned to work from Nagasaki at a studio located in Fukushima for companies based in Tokyo… But when I told him I had visited the year before, he remembered me and told me I could come whenever I wanted. I don’t remember exactly when that was, but it must have been around June or July… And then, I joined Dove in earnest in September.

Since you talked about your university anime club, have you done any independent animation with them?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Oh, yes, we did! But you know, that didn’t move one bit. We didn’t know one thing about how to make animation. A lot of animators have done some amateur work before going pro, right? But ours was a real joke. The legs and arms of characters didn’t even move, and we didn’t know the difference between key frames and in-betweens… I did it because some classmates wanted to. If they hadn’t been there, nothing would have happened.

Does the film still exist somewhere?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: At least, I don’t have it.

Back then, we’d record things on video – we used Betamax tapes. So I think I had it on a tape somewhere but recorded something on top of it and lost it. (laughs) I only realized later. (laughs)

What a shame!

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: No, no, it’s better that way! (laughs)

So Dove was in Fukushima prefecture, but of course, Sunrise was in Tokyo. How did you communicate? Was it all by phone?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Basically, for the meetings, Mr. Ihata would either go to Tokyo himself or lend his car to someone. Do you know about Mr. Ihata?

A bit. How he was originally at Mushi Pro, then went over to Sunrise…

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: That’s it. He went from Mushi to Sunrise, helped with the creation of Sunrise, and worked as “animation producer” on works like Combattler V, Voltes V, Daimos[2]… The thing with Sunrise is that all the staff except producers are freelance – so the animators, the episode directors… Mr. Ihata had originally applied to Mushi to do animation, but he happened to have a driving license, and back then, not everybody had one, so they had him work as a production assistant!

Apparently, the same thing happened to Masami Suda at Tatsunoko. (laughs)

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Yes, what they told Mr. Ihata was that he’d be more useful working as a production assistant. (laughs) And later, he started doing animation. Then, a bit later, he was involved in the creation of Sunrise, and his job as animation producer was to handle animators – I wouldn’t call it management, but he checked everybody’s schedules and things like that. He was also the one who opened a route for Sunrise to work with Korean and Taiwanese studios. At the time, only Tôei had subcontractors in the area, but he created contacts with Sunrise. Other people took on his role when he left.

Because, of course, this was pretty demanding, and his health deteriorated. So he went to Iwaki to recover, and as time went by, he slowly started to take work again. That’s how it began, and of course, he had close connections with Sunrise. Back then, nobody did that kind of work outside of Tokyo, and chronologically, it was in the middle of the anime boom, so that naturally attracted a lot of university students who came from the area and liked animation. First, Ihata accepted them to do in-betweens, and as it went on, it grew and became studio Dove. For instance, Misao Abe, who’s the president now, joined back when she was in high school. She’s one year younger than me, but she’s still my senior! I think she started out on Daiôja, so around 1981… But basically, that’s the story behind Dove’s creation.

As for when I entered in September 1983, there was Mr. Ihata, and the two active key animators were Kôji Koizumi[3] and Hitoshi Waraya. As for in-betweeners, there were 7 or 8 people, including Abe. Koizumi and Waraya entered around the end of Dougram and never did any in-betweens – they immediately started from the second key animation. Ihata directly gave them his rough layouts and the general indications for the movement to do key animation from. I believe Ihata did the timesheet as well at first, so it really was just like second key animation… They started out directly from that, and six months after I joined, they started doing their own layouts, which Ihata then checked. I remember asking them when they first did the timesheets themselves. I think it was episode 35 or 41 of Votoms?

In your case, did you start the same way?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: I just did in-betweens. If I remember correctly, my first in-betweens were on episode 31 of Votoms… After that, I did Dunbine and a bit of Giant Gorg. So just Sunrise work, basically.

And how were the pictures delivered from Iwaki to Tokyo? Did production assistants from Sunrise come to Dove?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: No, it was all delivery!

Oh, so did any drawings ever get lost?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: No, not at all! Amazingly, that never happened! But sometimes packages got mixed up during the trip and were sent back to us, so they’d arrive late… Ah, and there were times when we never received deliveries from the Taiwan studio!

Oh, I wanted to ask about that. Dove had all kinds of branches, right? When was the Tokyo one created?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Hmmm, I don’t really know about that… But perhaps sometime around 1987… You know there were lots of branches: there was one in Sendai, and…

The earliest one was Sendai?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: I think it was.

Then Tokyo, and there were the ones in Taiwan and Korea?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: At some point, there was one in Mito, Ibaraki prefecture. So there were two studios, the one in Koriyama and the one in Mito, but it didn’t last long. Sendai existed for some time, but eventually, it closed down, so the last remaining are the Tokyo branch and the main studio in Koriyama.

And also the Seoul one, I guess. After I left, I believe they created another studio in Vietnam, and that one might still exist. But I’m not sure about all that.

“They told me that if I had time to go to Korea, I’d better use it to work on corrections”

Have you ever gone to Korea?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: No, never! We started working with Korea at the time of Gundam F91[4]. I don’t know if I should say this (laughs) but, basically, everybody knew that we’d never meet the deadline. It came out sometime in February or March 1991, right? But in September 1990, there was still no animation completed! We had the 30-second preview but nothing more, apparently. Of course, that was pretty bad, and we still had a deadline to meet, so Mr. Ihata, who had had that experience back in his Sunrise days, was asked to try and find a way out in Korea. That was the origin of the Seoul studio. But before that, we didn’t work with foreign companies… Or maybe we did, actually: because Mr. Ihata still had his old connections, I guess we sometimes worked with a studio from Taiwan.

Did the Korean animators just do in-betweens?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: They did everything from second key animation. The layouts were done in Japan, but then the key animation or second key animation would be done there. It was basically that way until I left. At some point, they asked to do layouts themselves, and we let them try, but what they did was pretty much unusable…

I see. You just talked about F91, where you’re credited as “assistant animation director”. Concretely, what part of the film were you responsible for?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Well, you see, at first, I just entered the production as a key animator. It was around the 1990 Golden Week, so late April, that we had the first meeting, and Mr. Ihata told me that I was supposed to be the only Dove animator on the film. I was working on the Patlabor TV series at the time, doing both key animation and animation direction, but it was nearing its end, so I stopped doing key animation on it and transferred to F91. I started from the layouts there.

I haven’t rewatched it in a while, but I think that the first scene I was in charge of was when Cecily is taken away at the spaceport, and Seabook tries to save her in the Guntank. I did the layout and keys for that, but the thing is that the animation director completely redrew my layout. It was completely different. (laughs)

Was the animation director for that part Shûkô Murase[5]?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: I think it was… But don’t take my word for this.

What I’ve heard is that Mr. Murase was meant to be the only animation director at first and handled the colony attack part and that after that, Takeo Kitahara came to fill in…

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Yes, I can’t say it’s Murase’s fault or anything like that, but I did hear the same story: if it had been just him, things wouldn’t have advanced. But I think the key animation was late in the first place.

As for my other scenes… You know, the one where the kids try to get out in this sort of capsule…

When they escape from the colony?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Yes, that must be it. I did the layouts, but the key animation was done by Sueko Kiguchi. And then it was already September. (laughs) So it was decided that I’d work on the rest of the film as well, that we’d use the help of Korean artists, and Mr. Ihata asked me to supervise the layouts and key drawings made by the Dove artists. At first, I thought Murase or Kobayashi would be chief animation directors and that they’d look over my supervision, but actually, they didn’t. (laughs) That was crazy! I didn’t have the experience! I had just done a bit of animation direction on a TV series, that’s all…

Working on a film was pretty different…

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: But I had to, so with Hitoshi Waraya and Shin’ichi Sakuma, we started doing our layouts and sent that to Korea. Back then, I was told I might have to go there, so I made a passport, but in the end, only Waraya and Sakuma went because there was no time for me to go. (laughs) They told me that if I had time to go to Korea, I’d better use it to work on corrections. (laughs) And even those two spent all their time in Korea fixing drawings or sleeping at their hotel… And then, when they came back to Japan, they kept fixing drawings. (laughs) But well, that’s what happened, and by miracle, we managed to deliver the finished film in time.

Back then, Seoul Dove didn’t exist. The relationship we had was just working together with a Korean company. If I remember correctly, it was called “Sôshin Korea”. They also worked on stuff like Cyber Formula…

Sunrise was pretty happy with the process because it made mass production possible. They wanted to keep using it, so they talked with Ihata, who went to Sôshin Korea and integrated them under the name Seoul Dove. I think that happened sometime in 1991. It was still Sôshin Korea during the first half of Cyber Formula, and by the second half, it had become Seoul Dove.

Still, on F91, the theatrical and video versions are a bit different…

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Aaaaah, yes!

Corrections were made, right? Who was the animation director in charge of those changes?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: They should have been done by Murase. I think he fixed the characters again. But, basically, there was no time for him to do everything, so what happened is that the people originally in charge of each scene did the corrections themselves. So I did some corrections myself, and Sakuma as well…

“Koizumi really thought about the meaning of each shot and movement before he drew anything”

I see, thank you. Going back to Dove itself, Sunrise had a lot of other subcontractors, like Nakamura Pro, Anime R in Osaka… Was there any competition or rivalry between studios?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: There was actually no communication between us, but yes, there was definitely some rivalry. The problem is, there was no way anyone could win against Anime R. (laughs) But yes, we’d look at each other’s work, copy what we could, and things like that.

As expected from Anime R. (laughs) One of the most important artists at Dove was Kôji Koizumi, right? What kind of person was he?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: First, Koizumi was extremely polite. He’d never get angry, whatever happened! But he was very strict when it came to work. When I arrived, he had just been promoted to key animation, and it felt like I was watching it live as he got better and better.

So, what would you say was his strongest point as an animator?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: First, I’d say it’s how serious he was. At first, I was the kind of person who’d read the storyboard and just kinda followed it, but Koizumi really thought about the meaning of each shot and movement before he drew anything.

Aside from Mr. Koizumi, did you have a master or someone who influenced you?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Well, I received lots of influence from Koizumi and Waraya… Also, I joined Dove right at the moment when Mr. Ihata stopped doing anything other than animation direction, so I didn’t really learn by watching his layouts or drawings, but I learned a lot from his corrections. Outside of Dove, maybe the major influences were Norio Shioyama[6] and Tsukasa Dokite[7]! I only worked with Dokite much later, though. In terms of individual drawings, Shioyama was pretty big: for a long time, I wanted to draw in the same way as him.

Talking of Tsukasa Dokite, should we say you’re more of a Yoshikazu Yasuhiko[8] person? Rather than a Tomonori Kogawa[9] person?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Aah, well, you know, that’s pretty difficult! I didn’t work on any Yasuhiko production aside from a few in-betweens on Gorg, so it’s not like I had a lot of direct contact with him or his work. Whereas around that time, Kogawa released his animation manual, right? I used it a lot at some point – even now, I have it at home! It’s pretty run-down now, though! (laughs) So, in terms of how I draw, I’ve been strongly influenced by Kogawa.

The thing with Dokite is how good his corrections were. Back then, most animation directors fell into one of two categories: the ones who just fixed the faces and the ones who redrew every pose. But Dokite struck the right balance between the two approaches. So, for example, on a given movement, any other animation director might just redraw every frame. But in that case, you wouldn’t know what was wrong. Whereas Dokite might keep most frames as is and just change one pose on one drawing. It felt like he was saying, “Look, given what you’re going for, it’s better if you did it that way instead.” And that was always very instructive. That’s why I kind of consider Dokite as my spiritual master.

Back when you worked on Dirty Pair, Dokite was freelance, right?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: I believe he was at Sunrise’s Studio 4…

As a freelancer or in-house employee?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: As a freelancer, he just worked at Sunrise.

So he just had a desk there, is that it?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Yes. He’d also use various names like “Studio Zipang”, but I’m not sure what the relationship was with Sunrise. At least, he made his Sunrise work at Sunrise. But I’m not quite sure either. Since I wasn’t in Tokyo, I don’t actually know that much about how things went there.

In the later part of your time at Dove, you also worked a lot with Shin’ichi Sakuma, right? Was he something like your student?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: You could say that, but he actually didn’t start working that long after me. Probably just a few months. But in his case, he started around high school. Also, he was at the Koriyama studio at first. He came from the area, so he’d come to the studio after school to help out with in-betweens. I guess he graduated in the Spring of 1984, and that’s when he officially joined Dove. But I believe he was already there to some extent in December 1983. But now that I think about it, that means the Koriyama studio already existed back then!

So that would mean that, for example, the episodes you were animation director for and the episodes he was animation director for were made in different places?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Not really. At some point, Sakuma… (thinks) Was it when he graduated? He came to Iwaki. I think he was only in Koriyama during high school. Then, when the Sendai studio was created, he became its leader. That must’ve been at the time of Mister Ajikko…I think that by F91, he was back in Iwaki…

“There are lots of lies in the credits”

Coming back to you, starting from the time of City Hunter, if one looks at credits, your name starts appearing everywhere.

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: (laughs)

For example, you’d animate half an episode by yourself, do key animation and animation direction on the same episode, and you became the core of the rotation of shows like Patlabor. How could you be so fast?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Actually, there are lots of lies in the credits. Until V Gundam, you can more-or-less trust them, but if you take things like Raijin-Oh, they’re pretty messed up. On that show, Dove would alternate between 3 different crediting patterns… But actually, everybody was working on every episode in most cases, at least for the animation direction. So if you’ve got either Nishimura, Sakuma, or Waraya credited as animation director, it means the animation was subcontracted to Dove, and then in general, I’d supervise the characters, Waraya the mecha, and Sakuma would look more closely at the layouts or key frames. But then I was often called on to another series in parallel, and in such cases, Sakuma would take over as character animation director. It’s just that the credits kept noting the three of us in rotation.

Ooh, I get it. If you did character animation direction, does that mean you were better at drawing characters than mecha?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: I wasn’t very good at mecha. (laughs) Waraya was good at it and fast, so he did most of it. So, for instance, in the second half of V Gundam, I think I let him supervise most of the mecha scenes. I did them myself at first, but I was neither as good nor as fast as him.

Around that time in the early 90s, let’s say on Patlabor, how long approximately did it take to animate an episode?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Basically, around four weeks. For the key animation. Plus one week for the animation director to do their job. But by the time the animation director was finishing their work, animation had already started on the next episode, so I guess you could say four weeks.

I see. Today, layout, first key animation, and second key animation are completely separate stages, but how was it for Sunrise’s productions back then? You already mentioned second key animation earlier, but…

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Well, key animation’s always been the same, but in Dove’s case, we started sending the second key animation to Korea, so… It was pretty much the same layout/second key animation division you might see today. The drawings we sent to Korea already had the timesheet attached, so in today’s terminology, it would be the first key animation. But it wasn’t clean drawings like today’s keys. Then, in most cases, the animation director didn’t supervise or correct the layouts like they do today. It wasn’t like that in Dove’s episodes, and when it became standard in the industry, around the time of Gundam Wing and Gundam X, schedules were so tight that we didn’t have time to do it. So Mr. Ihata went to Sunrise to ask them to let us do things the old way.

I see.. As discussed earlier, you’d often do both the animation and animation direction on your own episodes. But I guess there’s no way you’d correct your own drawings yourself?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: No, I did correct myself! But not very often…

So when you didn’t, what happened? For example, were your drawings corrected by Mr. Sakuma, or…?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Around the time of Raijin-Oh, we sent the drawings to Korea, so I mostly stopped doing key animation at that point. But I don’t remember asking Sakuma to correct my own drawings, or only exceptionally.

If I’m credited under key animation, it pretty much means I just did the layout or the rough keys. But these were pretty rough, so the people from the Tokyo studio cleaned them up and added a timesheet most of the time. And then, when we started using second key animation, I believe it was either Sakuma or me who would check and correct it.

Going back again a little, on your mid and late-80s works like Dirty Pair or City Hunter, the drawing style was always so different between each episode. Did the episode directors specifically leave animation directors and each episode’s team a lot of freedom?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: I’d say it was more Sunrise’s approach back then to let animation directors do their thing, and I don’t think the episode directors would say anything. A lot of the episodes were subcontracted, and in many cases, the animation directors were in that situation where they could correct their own drawings. It was pretty fun, even to watch! (laughs)

But that changed at some point, didn’t it?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Well, when I started doing animation direction, it was still like that, and it’s not like I felt things change all of a sudden.

But things are different now. I’d be curious to know when things changed.

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: I see. That would be the 1990s, I’d say. But even before that, I got yelled at because my drawings were too off-model… (laughs)

“At first, I wanted to draw cool, impressive things, but around the time of Dirty Pair, I realized I was better at cute and comical stuff”

Regarding your own work, first, I’d like to ask about Patlabor. The quality of the OVA series was pretty high. How did you manage to rival such a level on a TV production?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: No, it’s not the same level at all. (laughs)

Come on, the TV series is pretty well-made!

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: There wasn’t anything special about it anyway. It was just like any other series. But personally, it did feel different since it was my first time as an animation director. Well, actually my first real job as animation director was on SD Gundam Warring States Legend, which was shown just before the first Patlabor film.

You also did character designs on that, didn’t you?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Oh yes, I did! (laughs)

What designs did you do precisely?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Pretty much all the SD Gundams and the small objects and accessories that come up on screen. Things like a phone box that just appears for a single cut…

How was it drawing SD characters?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: It was fun! At first, I wanted to draw cool, impressive things, but around the time of Dirty Pair, I realized I was better at cute and comical stuff. After the Dirty Pair film, I worked on City Hunter, and there unexpectedly was more comedy than action stuff, so I really enjoyed it. I looked forward to SD Gundam for the same reason – but, well, the proportions of SD characters were kinda difficult in the end.

Also, it’s not like I was alone on it: people like Susumu Yamaguchi or Yoshiaki Tsubata were starting to get good, and I tried to correct them without losing what made their drawings so appealing. After that was Patlabor, and I tried to keep that mindset: not make everything in my style, but rather keep what made the original drawings good.

Also, in Patlabor’s case, we did have the OVA as reference. But the style in the OVA is completely different in each episode, so it wasn’t really useful. (laughs) But there were Masami Yûki’s manga and Akemi Takada’s references – I tried to keep close to them, but I actually didn’t do that a lot!

There was also the first movie. It wasn’t made by Sunrise, but did you watch it back then?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: I did! I lost it when I saw it. (laughs) I think it came out sometime in June, but it took time to be shown all the way to Iwaki, so by the time I watched it, I was already scheduled to work on the TV series. And when I saw it, I didn’t know what to do anymore. (laughs)

After that came the Eldran series[10], right? You worked on Raijin Oh’s opening…

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: No, I only worked on the ending!

Is that so? I thought you were credited on both… Did you animate on any other openings or endings?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: I also did a bit at the end of the opening of Mama is a Fourth-Grader!

Ah, the one whose storyboard was by Yoshiyuki Tomino?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: That’s right.

I had heard that story, but I wasn’t sure.

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: It’s true. I worked with his storyboard, after all.

No other opening or anything on the Eldran series, then?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: None.

Did you do any gattai scenes or anything?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: No, of course not! I can’t draw mecha! (laughs)

Ah, that’s right! (laughs) On the Eldran series, it seems that Daiteiô was meant to be a TV series at first. Were you scheduled to work on it?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: No, not at all! I wasn’t even aware of it. I had already left the industry by the time it happened. But actually, I wasn’t really involved by Gozaurer… By Summer 1992, I worked on Ganbaruger and Mama is a Fourth Grader at the same time, and I dropped the latter to switch to V Gundam.

Well, your name always appears everywhere, so it’s easy to get lost. (laughs)

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Yes, even though I might not have worked on something, my name still appears. (laughs)

“Tomino’s incredibly good at transmitting the things he’s imagined”

Anyway, I’m glad we got to V Gundam because that’s what I wanted to ask about. You weren’t in Tokyo, but did you have any opportunities to meet or talk with Yoshiyuki Tomino[11]?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: For V Gundam, I attended a lot of the animation meetings, so we did meet.

How was it?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: (pulling a face)

(laughs) I’m sorry!

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: The thing that first comes to mind is in the first episode – what was supposed to be the first episode, at least.

Yes, episode 4 became episode 1 at the last minute. Did that influence your work a lot?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: We were just so confused about all of it and only understood what they were going for when we watched the broadcast. I think they asked us to draw some additional shots so that it would make more sense, but I don’t really remember everything…

So, you knew what would happen before it was broadcast?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: We did. They just told us it might become episode 2 or something, and we were just “???”.

Watching it nowadays, it doesn’t make any sense.

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Right? I believe it’s because the Gundam had to appear in the first episode or something like that.

So I haven’t rewatched V Gundam recently, but if I remember correctly, in that episode, the beam rotor of a Zolo mobile suit destroys a building, and there’s a shot of the debris falling to the ground. During the meeting we had for that episode, Tomino drew some sketches for that shot, and when I saw them, I was surprised by how good they were! I can still remember them.

Tomino always says that he can’t draw, but he’s actually pretty good, isn’t he?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: He is. Maybe his drawings aren’t perfectly complete as is, but he’s incredibly good at transmitting the things he’s imagined.

The thing about Tomino’s storyboards is how information-heavy they are. Are they difficult for animators to follow up on?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: They are! Well, they certainly were difficult compared to other things I’d worked on, and honestly, I feel like my work doesn’t really live up to them.

Aside from that, the big problem I had with V Gundam was that we were told to animate all of it on 3s at first. But I was the type to add lots of detail that just lasted one frame – I did that kind of stuff a lot on Dirty Pair or City Hunter – so that constraint put me in a bind. I wasn’t quite sure how to draw anymore…

On V Gundam, did you have any opportunity to meet Hiroshi Osaka[12]?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: We just met once for Gundam 0083: Stardust Memory. But it was very serious, so we didn’t really have any opportunity to talk.

I see. What do you think of his V Gundam designs?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: They’re pretty difficult.

Are they? That’s surprising to hear.

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: It’s like they don’t have many quirks. So you don’t know what to base yourself on to draw on-model. They’re the kind of design anybody could like; they don’t feel that unique. It’s like I understand what Osaka’s style is about, but I had no idea what I should do to imitate it or how I should draw. So it was pretty hard: I tried a lot of things, and every time I watched the broadcast, I realized my drawings were completely wrong.

There were a lot of very strong teams on V Gundam’s rotation. There were Mr. Murase’s episodes, also the Gainax episodes…

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: The Ashi Pro episodes are good, too.

That’s right. Were you paying attention to what the other teams were doing?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Of course, I did, to some extent, but it didn’t go further than “Wow, the others are good!” or “There’s no way I can draw as well as them”. However, the gap didn’t feel as huge and as frustrating as it had at the time of Galian or Layzner, though.

Your episodes on V Gundam are pretty good in their own right!

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Thank you.

Is there any scene or shot you particularly remember?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: To tell you the truth, I mostly just have regrets about V Gundam. And, well, it’s not really something I liked or anything, but around episode 10, when I went to the animation meeting, they told me they’d kill off yet another member of the Shrike team. And I was like, “Wait, again??”. (laughs)

Ah, so that depressed the staff, too?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: I guess it did… Then, around episode 30 or something, the bike battleships appear, right? I distinctly remember I liked that after I read the storyboard.

Did that happen often? That you’d like the stories and things you were animating?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Yes, it did.

“Just reading G Gundam’s storyboard made me laugh”

In a recent interview for Febri, Yûsuke Yamamoto[13] talked about how in Tomino’s works, the usual expressions and patterns that you can see in anime were forbidden. Did you feel any of that?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: My approach was pretty much to not pay any attention to anything that wasn’t said explicitly. Because it was up to the episode directors to make the decisions. On my end, I rather like cartoony, exaggerated drawings, so I’d say that I was not that suited to V Gundam overall.

So I guess you were a better fit for things like the Eldran series shows?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Yes, you could say that. It was easier for me. But that makes me remember Haro in V Gundam – he keeps jumping around, and his shape always changes, right? I was the one who’d deform Haro the most. The more the show advanced, the more I did it, and I was pretty fond of doing that because I was probably the only one going that far!

After V Gundam came, of course, G Gundam. It’s the first Gundam TV series that Tomino didn’t direct, and I guess you could say it’s a bit of a strange series… How did it feel for the staff?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Well, in my case, I first read the storyboard to get an idea of what kind of movement I should go for – something serious, or something comical. On G Gundam, the original designs were by Kazuhiko Shimamoto[14], right? I love his work and have always been reading it, so from the very start, I went in with the understanding that it wouldn’t be that serious.

But my problem as an animation director was that it took me time to get used to the characters – something like three months before I could say I had caught on the characters. So the beginning of each production was always difficult… Which wasn’t so much the case for G Gundam because it was so different from other Gundam series. Just reading the storyboard made me laugh.

Did you meet director Imagawa?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: I never did! I stopped going all the way to Sunrise around that time. The round trip took around a day, and I could have been spending that time doing corrections!

But you must have gone to Sunrise, at least for Gundam X?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: I didn’t. I didn’t on Wing either. But for both, the director of the first episode and a member of the production staff came to Dove, so we did have a proper meeting at the beginning of the production.

“I think Tifa was something of a miracle”

So, how did you end up doing the designs on X?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Well, Wing ended up being produced almost entirely in Dove… At first, there were other animation directors like Atsushi Shigeta and Yoshihito Hishinuma, but…

X was pretty much entirely made by Dove, right?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: That’s just a story I’ve heard, but on Wing, the storyboards got delivered later and later, and in the end, the designs for each episode got late as well. It went to the point that we started doing our own designs at Dove, because it would be… How do I say it…

More efficient?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: You could say that. Or put another way, they put the responsibility of the schedule on us! There wasn’t even an audition. I just think people at Sunrise decided on me. At least, Mr. Ihata just came and immediately told me to do the designs.

So before X, there were usually auditions for the character designs?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: There were. There was one for Victory, and I participated.

Aaah, I’d like to see those designs!

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: No, I don’t even remember what I drew! And, of course, I don’t have copies at hand.

Actually, regarding your designs on X, particularly Tifa, they feel close to Murase’s designs on Wing…

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: As you could expect, I spent a year working on Wing, so I ended up influenced by those drawings.

It feels like Yasuhiko’s influence went through Murase to you. Especially the way you drew the eyes.

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Well, it’s always been the same. I like to borrow things from the people I like, and actually, if I don’t, I feel like my own work isn’t that good, so that’s how I draw. But I don’t just copy people – I mean, in Wing’s case, what you can see on the screen and Murase’s designs are pretty different.

Is that so? This is probably a pretty hard question, but is there any character from X that you like more than the others?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Tifa, of course!

Ah, I knew it.

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: But what’s special about her is that she’s got nothing special, or at least that’s what I think. But she became distinctive in some way as I drew… In that sense, I think Tifa was something of a miracle. Because, at the time, I only wanted to make things easy, reduce the number of lines – well, it might sound weird to say like that, but I just didn’t want it to be hard. (laughs)

Wing was incredibly popular with the female audience. Did you have any awareness of that audience when doing the designs on X?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: I can’t say I didn’t. Especially characters like the Frost brothers… But rather than designing them as characters that women would like, I guess I was just influenced by Wing here as well.

So, as we said earlier, X was pretty entirely made at Dove. I guess that must have been pretty tough?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Well, to talk about that, I need to get back to Wing. We did a lot of episodes on Wing, and there’s this story about the director leaving midway, right? Anyway, the schedule was completely off the rails. We only had two weeks to animate episodes most of the time. So we’d do 2 episodes out of 3, and the remaining one would be done by the freelancers Sunrise worked with. We went on with the same system on X, where basically only one-third of the episodes were made at Sunrise.

Is there any scene or episode you particularly like in X?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: A lot! I love a lot of things about it, but I guess the second half is really cool.

Did you contribute anything to the overall plot or themes or anything?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: No, we didn’t have any time for me to do that. I just received the storyboards and figured things out. Usually, the initial designs are made from the first planning project, right? Well, that’s what I did, and then I worked out the details as I read the storyboard and saw where the plot was going. And then, as things went, I made changes here and there…

If there’s any scene I particularly remember, it’s the one in the first episode, when Tifa and Garrod first meet the Gundam, and Tifa points her finger in front of her. Atsushi Shigeta animated that scene. His drawings were different from my designs, but when I saw them, I immediately thought, “Wow, Shigeta’s so good, let’s do it like he does!” That’s one of the things that left the strongest impression on me.

It depends on the people, but I think the reference designs are just a sort of mid-point, you see. Then, as I start doing animation direction, I keep looking for ways to improve on the designs. So, if you’re both animation director and designer, of course, you’re going to stray away from your own designs at some point.

“As the 90s went on, it became increasingly harder for animation directors to keep doing things as they wanted”

I see. In the 1990s, the animation style of Sunrise productions changed quite a bit. First, they stopped using shadows on the characters. Do you have any idea of why that happened?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: I can’t really say, but there’s one thing I’ve heard about V Gundam, at least. It’s that 0083 had made Sunrise really unpopular among cel painters. Cel painting companies started saying they wouldn’t work on Gundam anymore because the shadows on 0083 were way too intricate. So they removed the shadows on V Gundam as a sort of excuse to make up for that. Also, I guess that Tomino doesn’t like fooling the viewer by adding too many shadows on the drawings, so that might have played a part. But drawing without any shadows was pretty hard for me.

Looking at some episodes, for instance, Murase’s, the shadows are properly there.

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: That’s right. That’s because there were a lot of talks over whether we should or shouldn’t put shadows. At first, they told us we could put shadows on only 20 shots per episode. The shots that could have shadows were indicated in the storyboards! The problem was the Gundam: it’s white, and they move it on this trailer, right? We couldn’t just make it all white, especially when it’s standing, so they let us put shadows on the Gundam and then inside the cockpit… Before they told us that, I didn’t add any shadows, even if I saw that the other teams were doing it. So I drew all that time without adding any shadows, and then suddenly, I was told to draw some! I really remember that, it was pretty crazy.

In Raijin-Oh’s case, the character designs were pretty simple, so I think the effects were adjusted to them: since the characters looked simple, it would have looked weird if we had suddenly added very detailed shadows. Also, there was an OVA after the TV series, right? Since it was a better quality product, they told us to properly put shadows. But actually, nobody paid any attention to that and didn’t put shadows – that way, it still looked like the TV series.

Aside from the shadows, effects animation changed a lot as well, didn’t it? In the 1980s, on shows like Dirty Pair or City Hunter, you can feel Yoshinori Kanada or Ichirô Itano’s influence, but…

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Right, things were pretty flashy.

And, well, talking of effects, 0083 was pretty big, but before that, there was Gundam 0080. Did you feel the “Iso shock” at Dove?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Yeah, I thought it was amazing. Absolutely amazing – but I had no idea what to do to catch up, so while I did receive a big shock from it, it didn’t really impact my own animation. But clearly, the younger artists at the studio, like Shûto Enomoto, were heavily influenced by people like Mitsuo Iso or Satoru Utsunomiya.

As a last question, can you tell us what led you to leave Dove?

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Well, it’s only intensified now, but as the 90s went on, it became increasingly harder for animation directors to keep doing things as they wanted. I saw the direction things were going, and I felt that I didn’t have the strength left to adapt to it. I was getting tired of the mass-production system we had going at Dove: I had started as a single animator, and that’s what I wanted to do, but I had to kill off that aspiration to do animation direction and just keep raising the numbers. That became too hard at some point.

Another thing was Jurassic Park. There are a lot of close-ups of the CG dinosaurs, right? The CG was made digitally, of course, but the one who oversaw that was Phil Tippett, right? I loved his work, and I realized that, even though animating in 2D and 3D are different things, I could put to use the skills I had learned in 2D in 3D as well. And it was just the time when the Playstation came out, game cutscenes started developing, and video games in 3DCG really started selling. One of the games I liked was Policenauts because the story was so dramatic, and I realized it used animation, so it was already pretty close to what I was doing. It’s just as I was developing that awareness that Hideo Kojima, the creator of Policenauts, tried recruiting animators for his games. I read the recruitment offer on Newtype. So, I decided to try it out and applied. That’s how it happened. And I only learned later that I was the only animator who applied to that offer!

I see. It’s interesting because even though it wasn’t Konami, a lot of animators went into the video games industry at that time.

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: Yes, a lot went to Square.

Exactly. I’ve always been curious about that. I’ve heard that the salaries were pretty good, but…

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: I’d say that played a big part. Especially for the really good people – not like me; I wasn’t focusing on every shot; I was just like a cog in a machine made to put out drawings. But for the really good freelance animators, they’d spend days or weeks on certain scenes and only earn a few thousand yen in return… There’s no way you’d earn your living like that. So, of course, if there was some place that would properly pay for their skills, they’d go there.

I see. Well, I’ll ask Mr. Kôzuma about it next time.

Nobuyoshi Nishimura: (laughs) Ah, that’s good! I want to know what he has to say, too!

All our thanks go to Mr. Nishimura for his time and kindness, and to Ms. Nishii and Mr. Takahashi for the introduction.

Interview by Matteo Watzky.

Assistance by Dimitri Seraki.

Transcript by Karin Comrade.

Introduction, translation, and notes by Matteo Watzky.

Footnotes

This article would not have been possible without the help of our patrons! If you like what you read, please support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Oshi no Ko & (Mis)Communication – Short Interview with Aka Akasaka and Mengo Yokoyari

The Oshi no Ko manga, which recently ended its publication, was created through the association of two successful authors, Aka Akasaka, mangaka of the hit love comedy Kaguya-sama: Love Is War, and Mengo Yokoyari, creator of Scum's Wish. During their visit at the...

Ideon is the Ego’s death – Yoshiyuki Tomino Interview [Niigata International Animation Film Festival 2024]

Yoshiyuki Tomino is, without any doubt, one of the most famous and important directors in anime history. Not just one of the creators of Gundam, he is an incredibly prolific creator whose work impacted both robot anime and science-fiction in general. It was during...

“Film festivals are about meetings and discoveries” – Interview with Tarô Maki, Niigata International Animation Film Festival General Producer

As the representative director of planning company Genco, Tarô Maki has been a major figure in the Japanese animation industry for decades. This is due in no part to his role as a producer on some of anime’s greatest successes, notably in the theaters, with films...

Recent Comments