Among all the star action animators from Japan who have become famous over the years, Yoshimichi Kameda is probably among the greatest. Since his explosive rise to fame on Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood, his original take on Kanada-style animation has earned him countless fans and imitators. His work as character designer and animation director on Mob Psycho 100, chief animation director on Inu-Oh, and now animator on Hayao Miyazaki’s How Do You Live? have confirmed his status as one of the most important animators in Japan today.

We had the occasion to meet Mr. Kameda at all the festivals held in Japan in early 2023 where he reaped multiple prizes – the “best animator” prize at the Tokyo Anime Awards Festival in February and the Okawa-Fukiya prize at the Niigata International Animation Film Festival in March, both for his work on Inu-Oh. Following these occasions, we sat for more than an hour with Mr. Kameda to discuss his career, his work on Inu-Oh and hear what he could tell us about Hayao Miyazaki’s last film…

We also brought with us the recently published key frames collection 100%, containing many of Mr. Kameda’s original drawings and illustrations. Thanks to it, we could hear him explain how he works in utmost detail.

This article is available in Japanese. 日本語版はこちらです

This article would not have been possible without the help of our patrons! If you like what you read, please support us on Ko-Fi!

“All of a sudden all the people I dreamed to meet were there”

Thank you very much for taking some time for us. Actually, the other day, we went to see the Detective Conan film, it was great! Especially the bicycle kick scene.

Thank you (laughs). I did that scene, when he goes “come on!!!”

It’s really cool.

It has to be there, but it went really fast. It feels like the scene was over in a flash, and the timing is also a bit rushed…

Mr. Kameda, you’ve always been an Evangelion fan, so how was it when you finally had the opportunity to work on the films?

It’s at the time of Fullmetal Alchemist: The Sacred Star of Milos[1] that I first heard about 2.0 from Kiyotaka Oshiyama. I asked him about what he had done on the film, or some pachinko illustration… He told me all about it and showed the illustration to me. It was on a big paper, with those thick brushstrokes… I remember it really well: it was Evangelion, but he had drawn it in the same style as the wolves in Milos. So in the course of that conversation I told him I loved Evangelion. And back then there was Hidetsugu Itô, who had worked on Milos and was already meant to go work on the next Evangelion film, 3.0. And I don’t know how it happened, but Itô went to ask me if I liked Evangelion and offered me to work with him on the film. So that’s how I joined the production.

At that time, I had already sent my profile and portfolio to Khara, because I wanted to work on Evangelion so hard. But I had gotten no answer so I didn’t know if I had passed it or not, and there was Itô inviting me, giving me a chance to go… I was so glad, it felt like my feet weren’t touching the ground anymore, I thought I was dreaming… But it was the right time to go visit Khara.

So I went. It was back when they were making the opening for this program called Japa-Con TV, and they asked me if I didn’t want to be on it. I had no idea what that was! At the meeting for that, there was me, Takeshi Honda, Tadashi Hiramatsu, Hideaki Anno, Tetsuya Nishio and Itô… It happened immediately, without so much as an interview. I was there for the first time, that didn’t feel right… But yeah, the first time I went, I got to work on that opening. Evangelion had probably started already, but they didn’t know what kind of animator I was, so they probably wanted to test me with that.

After the meeting, we went to have a drink and talked all night long. I was still 26, 27? back then, really young. I was really impressed but – how do I say this? – all of a sudden all the people I dreamed to meet were there in the same room and casually greeted each other, there was no tension whatsoever. On top of that, they’re all super animators, right, but they’re all really casual. I was super nervous, but they all talked to me nicely so I got less stressed and the mood got really good.

The director and storyboarder for that opening was Mr. Hiramatsu, and he basically made no corrections to my work. The way it went was that there would be a small animation around each letter at a time, and I was in charge of the “pa”. Or maybe just the “a”. The theme was Japan’s future technology or something. So I had to illustrate it with Japanese robots, got reference pictures, like that “Asimo” by Honda, and they told me to do something with that. “You’ve got 3 seconds, so make the most of them” is what I was told. That was my first job at Khara.

Back then, I was obsessed with the Kimagure Orange Road opening “Orange Mystery”, and had been wanting to do something like that. So I was like, “this is it!”. You know, whenever I’m working, there’s always something I’m chasing after, and if there isn’t something like that, I can’t draw. At the time, I was looking for the right occasion to do this kind of stuff.

So before Evangelion, I got to work on Japa-Con TV. I don’t really know if it was a test or something, but I passed it and finally joined Evangelion 3.0. I got a scene to do on Kazuya Tsurumaki’s part of the film. During the meeting, Mr. Tsurumaki explained all kinds of stuff, and I listened to him, going “ok, I see, I see” and taking lots of notes on the storyboard until it felt like I was ready to go.

You know, on Fullmetal, I took liberties with the storyboards, redrawing things and all that… This time as well, I wanted to give it my all, so I did as I had gotten used to. I went “if I do it like that, it’ll look better!” and changed the angles of the storyboard to things I thought were cooler. It ended up looking completely different, and when I gave that to Tsurumaki, he started looking embarrassed. It was different from the storyboard, so he explained it all again from the top. He was there sitting next to my desk, going through all the cuts one by one, and I could only answer “I get it, I understand what you’re trying to say”. (laughs) “I’m sorry, I just went and did what I wanted and changed it, I’m sorry. Ah, this cut as well. And this cut too. But even if the angle is different, the acting is as you wanted, right?”. We talked about it, and I redrew everything following the storyboard, got the corrections, and that’s what’s in the film.

Thankfully, Mr. Honda praised my work, and Toshiyuki Inoue was sitting next to me, so I could see how he worked. It was a really amazing place to work in and I had a lot of fun. Seemingly they liked what I did, because they asked me to draw an Evangelion pachinko illustration. (Points at the key frames collection) I think it’s also in there.

Ah, yeah, this one?

That’s right. There are two illustrations in there, right? I drew that one first, and they liked it, so they asked me to draw the second one as well.

“I developed my style by combining Soul Eater and Imaishi’s animation”

I see… So, I believe that at the time of Fullmetal, you wanted to do action animation like Yutaka Nakamura, right?

Exactly.

What’s your relationship with Mr. Nakamura now? Is he like your friend, your rival? Maybe your master?

(laughs) No, no, no, nothing like that, he’s more like my spiritual master! Calling him a rival would be going way too far! If we were actors, I’d say he’s a big Hollywood star like Tom Cruise, and I’m just the regular guy playing an extra part in the background. He’s also very straightforward, always walking here and there in Bones chatting with people, and he’s also giving out the dôjinshi he sells every year at the Comiket…

Like Nakamura’s, your action animation is really intense and cool, but on the other hand, your designs are pretty cute and look child-oriented. Would you say there’s a gap there?

Hmm… Right, but what made me want to become an animator is Hiroyuki Imaishi’s[2] work, you know. And Imaishi draws these very comical characters, in the Gutsy Frog[3] style, but he also does this Kanada-style movement. He can do both cool action with a touch of comedy and gags.

There’s that, and then during Fullmetal, I tried something as intense and real as Nakamura’s work.I was thinking of how to incorporate that into my work, and that meant following in Nakamura’s steps. At the time, I was watching what he did on Soul Eater over and over. So I developed my style by combining Soul Eater and Imaish i’s animation.

Of course, I’ve done stuff like Doraemon and Parole no Miraijima where the characters have small proportions, and these probably fit me best.

Talking of Doraemon, I brought this flipbook with me, and it’s a really similar style, isn’t it? Like how the characters are very round…

That’s right. I drew that at the time of Space Dandy.

Is that why it’s SF? With this guy fighting aliens…

You could say I tried to combine the outer-space element from Space Dandy with Fujiko Fujio’s patterns from Doraemon on that one.

What’s the story behind that flipbook?

Well, you know Mr. Takahashi from Studio Break which puts out Shin’ya Ohira’s books. At some point he told me to make a flipbook, and I had 100 pages to draw. At first I thought I’d have to make something like what Ohira does… But Takahashi told me I could do whatever I wanted, without any prescribed theme. So I basically took what I was working on, the style I liked with those small proportions, and it turned into this Kanada-style SF action thing. But I didn’t know how to conclude it. It was fun at first, drawing this battle between some kid and an alien, but I didn’t know how to finish it so I kinda forced it with the final twist (laughs).

© Studio Break

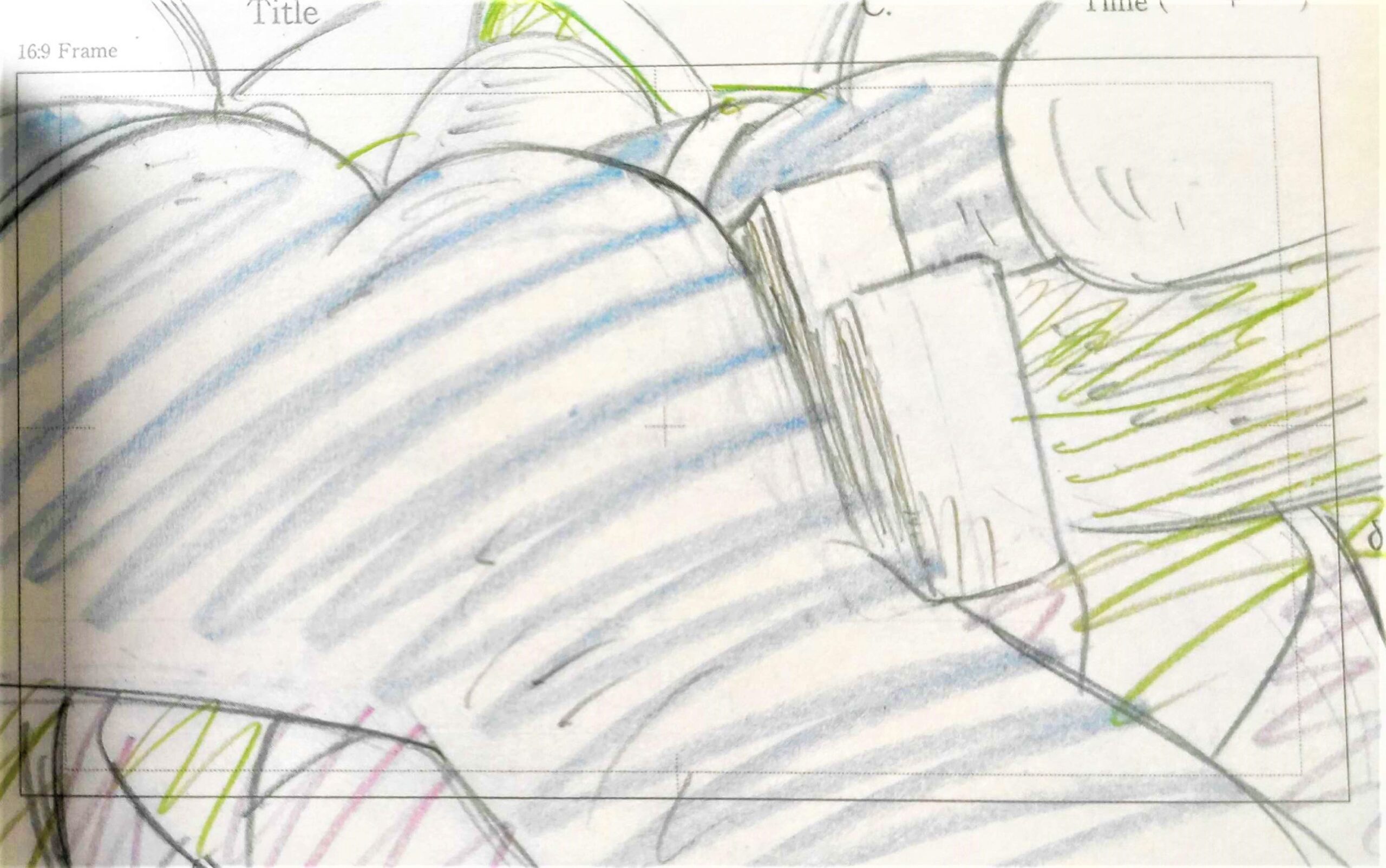

Weird question, but when I read that flipbook, I got really curious: why do you always put so much attention to drawing the butt?

(laughs) Ah, that’s right! Well, you know, Imaishi and Kanada[4] both draw these high or low angles, and so I started to think that was really cool: a high-angle with the perspective following the legs, the butt and the upper body. Since Kanada and Imaishi drew a lot of that stuff, at first I wanted to do the same. So I’ve been doing it all this time, and as it went the butt got bigger and bigger. Somehow I developed this habit: when there’s a high-angle like that, you can’t see half the body anymore (laughs). Talking about round, fat butts, there’s the ones Kanada drew in the Birth manga with that circular ruler of his. When I saw it for the first time, I thought that when you draw it like that with a ruler, even a butt can be cool! I think I have a big butt as well myself, so that’s how I ended up drawing them this way.

“It’s the way I draw now”

Sorry for the weird question. (laughs)

Also, I noticed that when I draw close-ups, it’s always either the butt or the eyes. (Flipping through the key frames collection) Here’s another butt. Isn’t there any closeup of the face?

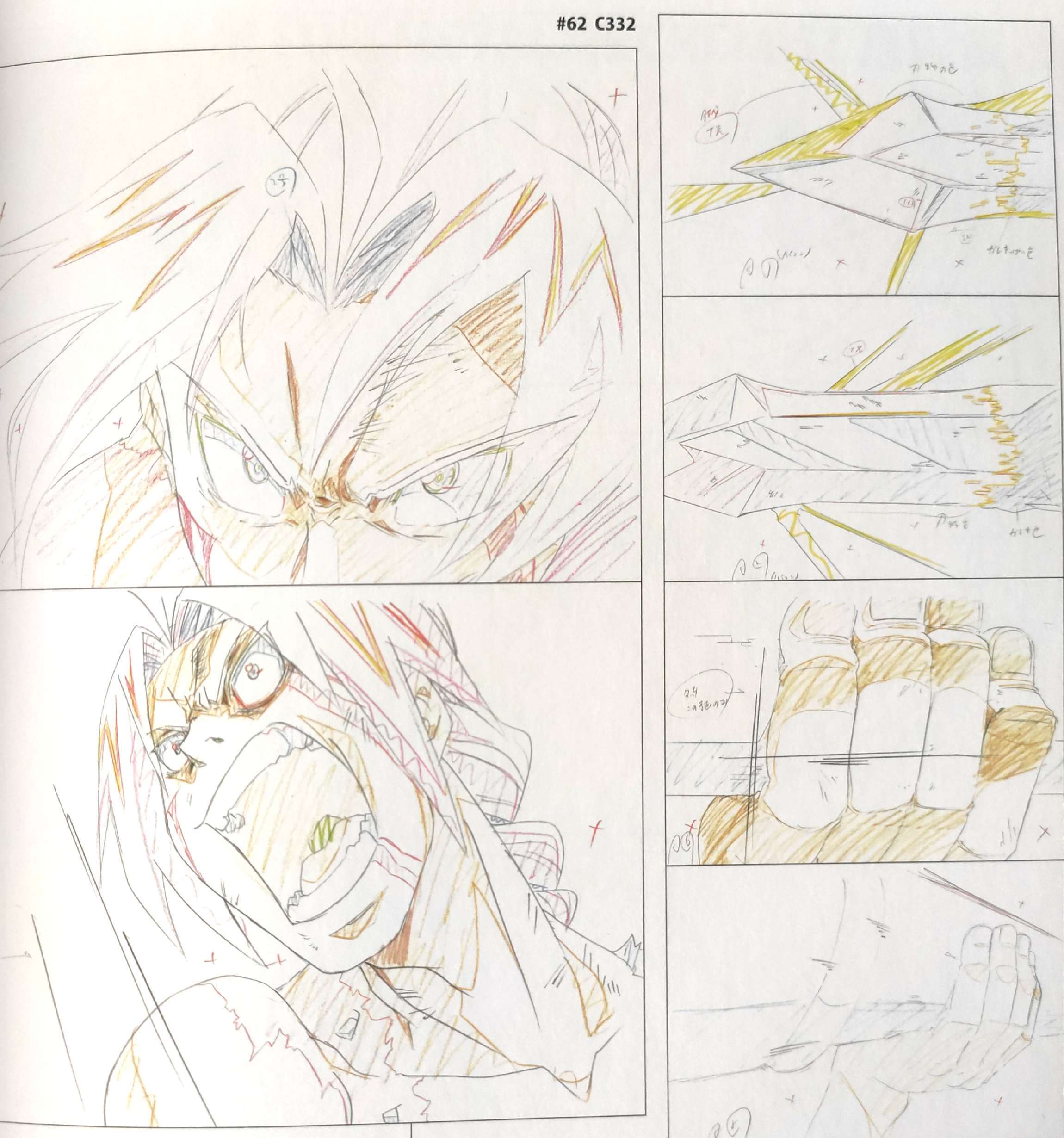

Here’s one. It’s a technique I came up with on Fullmetal: if you make a close-up close enough that the face takes up all of the screen, you can change the background and transition to some other angle. When I discovered that, I started inserting these big close-ups on the face, changed the background sheet and moved on to a different angle. I did that all the time. So on the flipbook, I did that with the butt. You can see it here as well, the key frames from The Sacred Star of Milos.

I have to confess, your work on Milos is among my favorites.

Is that so? Thank you very much!

Look at this one, it’s from the TV show. First the face comes close to the camera, right? And then it pulls back a little… And the next cut, the face comes close and pulls back again.

From 100%. © Studio Bones

Here as well. You have something flashing by on the front of the screen, to give a sense of depth. Then you pull it away, close back up on the face, let the impact sink in, then pull back and forward again. Looking at that key frames collection, I realized it had kinda become a pattern. But well, I still like it. Or rather, it’s just the way I draw now. (Flips through the book again) Look, it’s always the same: a close-up on the face and then pulling away. I did the same thing on the opening of Ousama Ranking: Treasure Box of Courage recently: close-up on the face, change the background, and then when Bojji comes close to the camera at the end, another close-up on the face and then pull in on the shoulder.

Talking of Ousama Ranking, you did your first storyboard and episode direction on a TV series on it, right? How was it?

I didn’t really know what I was doing while I was in the middle of it, but once it was done, I realized that maybe I could have done a lot more. But I guess I could say that I managed to turn it into something I like. So I feel like I’ve accomplished something, but I’m also still frustrated, as if I could have done more? It was more fun than I expected, though. That’s because the way to approach a series is completely different from what I do when designing characters. It hasn’t aired yet, so I don’t know what people will think of it. I think it’s fun, but… I don’t know if it’s the kind of thing people like. But at the moment, I’ve managed to calm down a bit about it.

We look forward to it! By the way, can you tell us what led you to join WIT Studio?

I was already an employee while directing that episode, and my next work is also going to be done at WIT. It’s the kind of thing that’s going to last for a while, so I won’t be able to take work from outside for some time, and I got an offer to join at the right moment, so I thought it would be good to try becoming in-house. I’ve been freelance all this time, so I don’t know what it’s like to be in-house. It was nice to be freelance, work here and there and take whatever job I felt like doing, but I’m the kind of guy who takes more than he can handle. To a dangerous degree. (laughs) I had been working on around 3 productions at the same time for a while, and it’s been physically exhausting. I had been wanting to just focus on one thing at a time, and it’s at that moment that I got the offer from WIT, so I thought it would be the right time to settle down. And well, obviously it’s more comfortable to be paid regularly each month… So there’s no deep reason behind it or anything. Let’s just say I want to try it out.

Are you teaching the new recruits in WIT as well?

We’re currently recruiting, and I think I’d like to teach them. To give them proper training, receive their help on my next work, and increase the staff of that work by even one person, would be good. That’s the kind of thing you can’t do if you’re not in-house. When you’re freelance, you don’t even have to think about anything, you’re busy enough with your own work.

In terms of training, I’ve already done some of that on the short Parole, though. I have some of the experience from it, so maybe I could teach people without having to think too hard about it.

Do you have any disciples already?

I wouldn’t say that… I don’t think you could call any of the animators who worked on Parole my disciples…

So any followers, or people like that?

Maybe people like that… They’re not my disciples, but there are people who seem to really like my work, like Takeshi Maenami or Kôsuke Katô… But it’s not like I’ve ever had the intent to teach them, they’re already good as they are.

In WIT, you’ve been working a lot with Claire Launay[5], isn’t she like an apprentice of yours or something?

It’s true that Claire seems to be looking up to my work, but she’s already very good and has her own style, so I don’t really have anything to teach her either. It’s more like she seems to love my work, so we talk a lot. I don’t know if it would be correct to call her a disciple or anything, but maybe a younger colleague I appreciate a lot would be alright.

And you, Mr. Kameda, do you have a master or a teacher?

A master, huh. I see. There’s nobody special I could point to. As an animator, there wasn’t really anyone who taught me the ropes. Back when I was an in-betweener, there was someone who taught me how to do it, but as soon as I started doing key animation, I didn’t get taught by anyone. It was just this more experienced animator who sat behind me in my first studio whom I’d ask about how to make a timesheet, draw a layout, and all kinds of beginner stuff.

Basically, all I learnt I got from Imaishi’s dôjinshi, videos of Kanada’s work, and Keisuke Watabe’s[6] key frames collection. I’d have all that piled on my desk and use it all the time for reference. If Imaishi did something in such a way, then I’d do it too. Also, there’s the layout collection issued by Ghibli. Everybody has a copy of that one. But the thing is, Ghibli’s layouts are in color, right? They’re made with colored pencils and everything. I tried making something like that once, and I got really chewed out (laughs). They told me stuff like “do you even know how to draw? You’re not in Ghibli here!” (laughs). I just nodded and said sorry (laughs).

Who told you that?

The animation director of that thing I was working on, I think. I remember very well getting scolded.

Did you get anyone angry at you for using a brush pen on your key animation?

Unexpectedly, that never happened. I started using it on Fullmetal? Or just before that, on Zettai Karen Children. I did in-betweens part-time on it, and also a bit of key animation under a pseudonym. I believe I already used a brush pen back then.

The reason I started using a brush pen is that I had been doing in-betweens on Seto no Hanayome, and the character designer Kazuaki Morita was super good with a brush. He used it on the package illustrations for the show. They were so cool I tried to imitate them, and started using a brush pen. From there I began to think that it would be cool to draw characters like that as well, but I figured that if I drew key frames with a brush pen all of a sudden, people would get a weird impression. So first I tried doing impact frames, like the ones Masahito Yamashita or Yoshinori Kanada did, but with a brush pen. If I just did it for impact frames, it’d go without a hitch. If the impact frame is in black-and-white, wouldn’t it look cooler with a brush-pen? That’s what I thought.

But now you’re not really using the brush-pen anymore, are you?

No, not really.

Why is that?

Why indeed (laughs). Everybody’s been telling me that since I’ve stopped using it, after One Punch Man or something like that? Well, I’ve been doing the designs on Mob Psycho 100, so I’m not an individual animator anymore. I have to supervise everything, and I haven’t had the time to add brush touches to my corrections. It’s become my main job now, that’s why.

So it’s not because you’ve switched to digital or anything?

I’m on digital now, but it’s unrelated. I drew the Ousama Ranking opening on paper, though, so I added some brush strokes and dirtied it up a bit. Now that I think about it, I haven’t been using the brush pen for the impact frames… But yeah, adding a few brush strokes really ends up making the kind of image I love.

“I was completely satisfied with what he had done on seasons 1 and 2”

Since you mentioned Mob Psycho… The characters look very simple, right, but I’ve heard that they’re actually really hard to draw. As character designer, what’s your take on this?

That’s the thing with characters drawn with so few lines: with just one line, the entire drawing changes. That’s what makes Mob hard to draw. Personally, I love stuff like Doraemon or Hajime Ningen Gyatorz[7] which have very few lines, so I’ve never had a problem with it. I’ve never found it difficult or anything. So I didn’t pay any attention to it at first, but then people told me about it and I realized, like, yeah, Mob’s eyes are actually difficult to draw. If you just change the tiniest bit, the entire balance of the face is gone. If the size of the eyes isn’t perfectly right, all the face looks bad, the mouth has to be put at exactly the right place, stuff like that. At some point, I realized all that and it became pretty hard for me as well.

By the way, back when I was still doing in-betweens, I worked on Ah! My Goddess. The character designer, Hidenori Matsubara, used to say this. His designs had so many lines, you see, to the point it seemed absurd on a TV production. But the reason, he said, was that with so many lines, you can’t notice if the in-betweens can’t follow. There’s so much detail, even if one part isn’t good, the picture as a whole still works. On the other hand, when there’s so few lines, the entire thing collapses if the in-betweener doesn’t do everything perfectly.

On Mob, I realized that it all depends on the in-betweeners, and the way they pick up some nuances or don’t completely changes the feeling of the original drawings. So I remembered Mr. Matsubara’s words, and I felt like I got what he meant.

On Mob season 3 you and Mr. Tachikawa moved from animation director and director to chief animation director and chief director. Why is that?

When discussions started for season 3, both Tachikawa and I were busy with other things, so the timing was a bit tight. Tachikawa was working on Blue Giant and the Conan movie, and I was on some other project which got me really busy. I was supposed to do the character designs on a film, so I had my hands full and wasn’t sure how much I could do working on a TV series at the same time. I didn’t know how much I would be able to work on Mob Psycho, so I suggested doing the character designs and just supervising things a bit as chief animation director. It was ok, but that film project didn’t happen in the end, (laughs) so I got more involved in Mob, supervised more cuts, and then served as regular animation director for episodes 6 and 12.

Why wasn’t there any chief animation director or chief director up to that point?

That’s because both Tachikawa and I like it when there are different visual styles. At the very beginning, we agreed that it would fit something like Mob Psycho to have slightly different styles each episode. You know, I’m the kind of guy who likes old anime where each episode had a different look because the animation director changed each time, so I hoped Mob could become a bit like that.

So in season 1, there’s Ken’ichi Fujisawa’s episode, and Gosei Oda’s episode, and my own, and the drawings are always different. We could develop something like that on the first season, and we kept it on the second one. But by the third one, all the young people who had worked with us had become big and were among the main staff on some other works, so we couldn’t gather them all together again.

So I felt that my role as chief animation director would be to pave the way, or set the general direction to maintain the overall quality. Season 3 has a rather serious story, so it’s not action-centered like season 2 but rather plot-centered. I thought I’d have to correct the expressions a lot more, and that it’d be better for the overall balance of the series if I were chief animation director. I was completely satisfied with what we had done on seasons 1 and 2, and it looks like the viewers didn’t mind the differences in style either.

That’s really good to hear, because nowadays, people always complain when the style changes. They get mad about off-model or whatever.

Yeah, it’s become like that…

Anyways, even though he was busy on other things, Tachikawa served as chief director. And then he suggested that Takahiro Hasui, who had done a really good job on season 2 episode 6, become the director. I agreed with him, and that’s how the core staff for season 3 was decided.

Are Mr. Hasui and Mr. Tachikawa very different? In the way they work, for instance.

They’re very similar. Hasui is really skilled, he’d answer immediately whenever I had a question, he’s very good. Whenever I’d go to his desk, he was always watching the first episode of the first season…

“I got a call to work with God”

Thank you very much. Now, shall we move on to Inu-Oh?

Finally! (Laughs)

Sorry for being so long (laughs). Can you tell us how you first met Mr. Yuasa?

The first time we met face-to-face was back when he was working on Kick-Heart. He was doing the VJ at a club somewhere, Roppongi maybe?, and the entire Space Dandy team went to see him do the VJ. But we barely exchanged any words, just greeted each other.

Anyways, I loved Yuasa’s episode of Dandy, I’ve seen Mind Game and I’m a big fan of Kemonozume and Kaiba, I’ve got all of them recorded. And after Dandy, what did he do, Ping Pong, right?

Ping Pong came after Kemonozume and Kaiba.

So after The Tatami Galaxy, right?

Ping Pong’s from around 2013, 2014 or something like that?

So maybe he was already working on Ping Pong just before Dandy… Anyways, I love Ping Pong as well, but it felt like there was no way we could ever work together. It made me happy just to work on the same thing as him with Dandy.

And then of course, Inu-Oh became the thing everybody in the industry would be talking about. You can’t do better than Masaaki Yuasa and Taiyô Matsumoto[8]. But we never heard anything more for some time. After a while, I was starting to think it was dead, and I got a phone call out of the blue. It was Eunyoung Choi, asking me if I was interested to work on Inu-Oh. You bet I was!

I had seen Satoshi Nakano, who was chief animation director with me, just before that, and he told me he had become animation director. Since Mind Game, he’s always been a huge fan of Yuasa, he’s probably the person in the industry who loves him the most.

He was like, “I can’t believe I get to work with God!”, and then just after that, I got a call to work with God as well. I thought I could handle a bit of key animation. I was pretty intimidated at first, I didn’t really know how it would end up looking like. I was dreaming, hoping it would look like Kemonozume or Kaiba… (pointing to the flipbook) There’s probably a bit of Kaiba in that, actually.

But in the end, it feels like Inu-Oh has the most realistic animation style in all of Yuasa’s works. Your animation rarely goes in that direction, so how was it?

It wasn’t as hard as I thought it would be. But the thing is, rather than just the style of the pictures, you never know what Yuasa has in mind and what kind of thing he’s going for. Of course, because he had worked with Matsumoto on Ping Pong before, everybody thought it would be something similar. But then they told me it would be completely different. Yuasa said all the time that he wanted something more realistic, but I have no idea what Yuasa’s “realism” means (laughs).

It’s not Ghost in the Shell, it’s not Patlabor… If it’s not, then what is it? I was lost about it all that time, and the only answer I could find was in Yuasa’s corrections. I had no clue, so as I was doing my key animation, I took a look at the corrections for the A part that Yuasa sent to Nakano. And yeah, it wasn’t like Ghost in the Shell or what the realist school does, but the same kind of reality you find in snapshots. In the shapes and the designs, there’s a sense of raw life…

A bit like Shin’ya Ohira’s work, right? There’s that “rawness” he’s always talking about.

Maybe that’s it. Ohira creates this rawness that isn’t quite real either.

But in Inu-Oh’s case, wouldn’t you say that’s perhaps due to the presence of Norio Matsumoto[9] or Atsuko Fukushima[10]?

That’s probably right. Actually, Nakano was really lost about it as well, he didn’t know what “realism” was supposed to be. Just as he was trying to figure that out, Atsuko Fukushima and Norio Matsumoto delivered their parts, and for all the rest of the movie he constantly used their work as reference. I don’t think Matsumoto received any corrections. Both Nakano and I constantly referred to the pattern of their drawings, the way they balanced out the amount of information. We used it as the standard, since their drawings were already perfect as is.

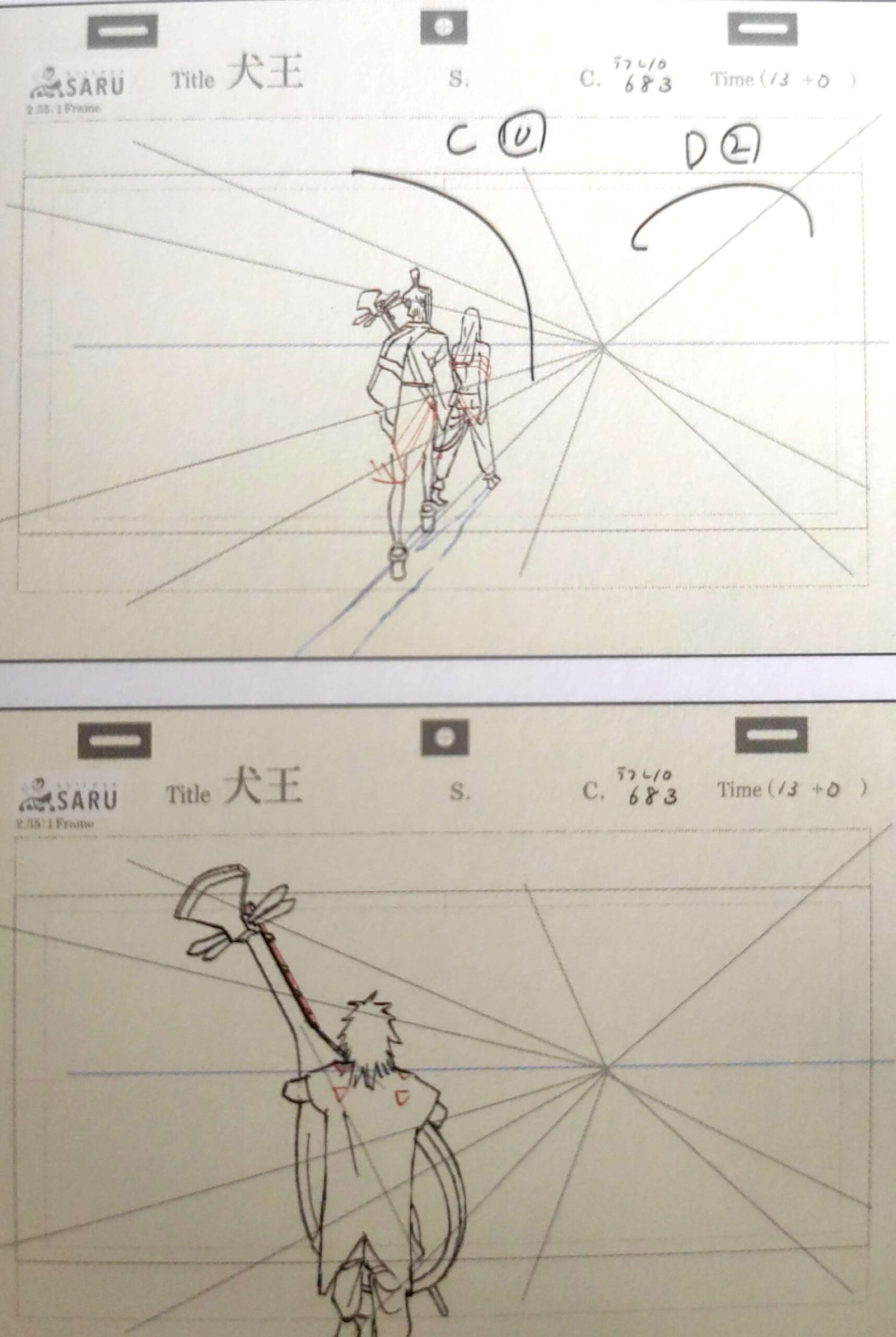

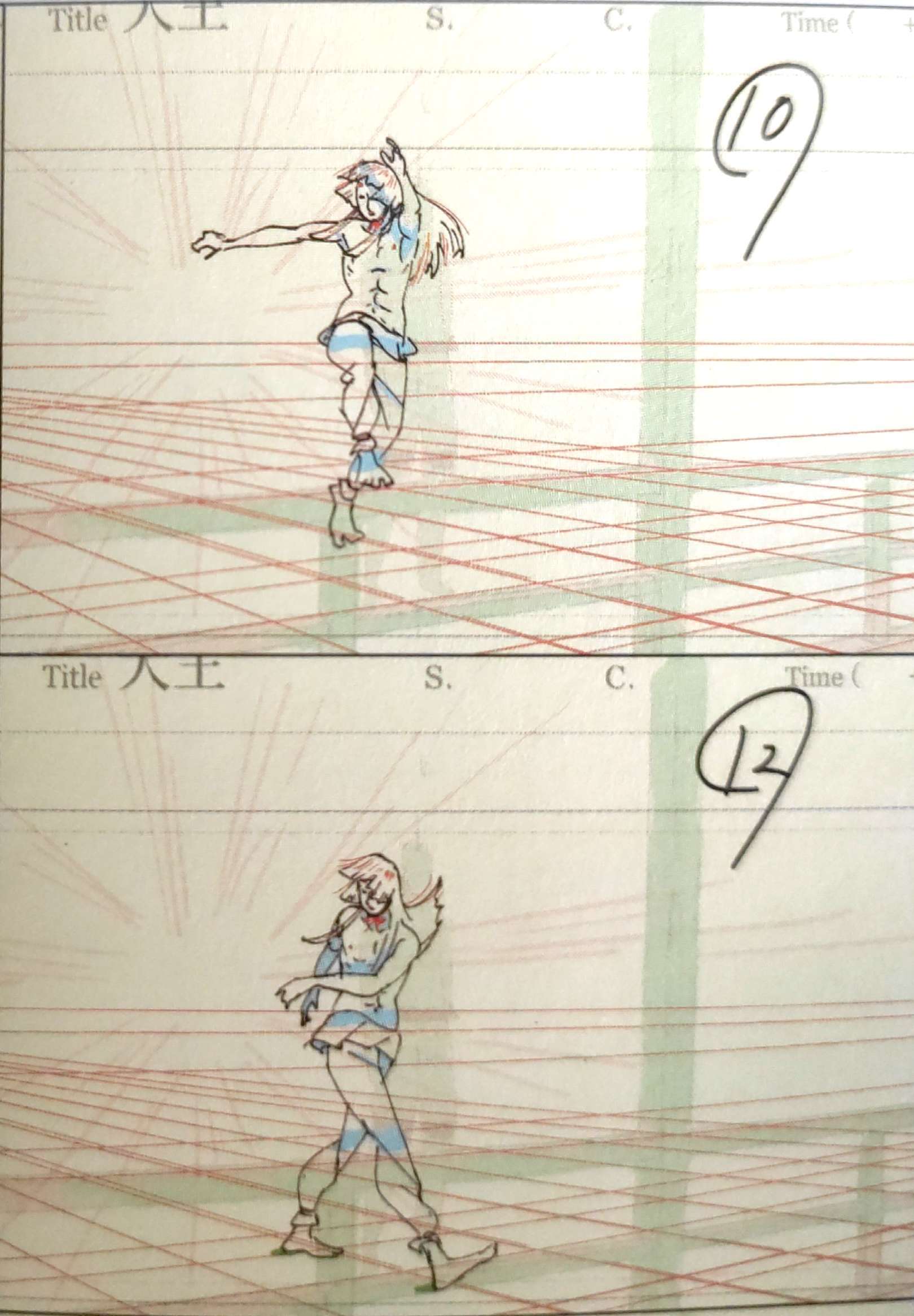

Looking at your own drawings, for instance on Inu-Oh’s dance scene during the climax, the vanishing point and convergence lines are always properly drawn, which is something I haven’t seen in the work of other animators. Was that Mr. Yuasa’s instruction? Or something you always pay attention to?

No, no instructions or anything! When I’m on paper, I have to make those each time or I can’t draw anything. That’s the good thing with digital: you can put the convergence lines on the top layer and leave them there, and they’re easy to see without getting in the way of anything.

From 100%. ©Science Saru

For this cut, I know the characters move from the front to the back of the screen. So I basically drew the lines all over so that it remains consistent.

From 100%. ©Science Saru

For the dance scene, there’s no background behind, and without the proper perspective, the character’s size would become inconsistent, so it’s necessary to have a good grasp of the perspective on the ground and where the railings go as you draw.

If I remember correctly, the backgrounds for that scene when they get on stage are in 3DCG, right? Did you use 3D layouts as well?

That’s right, the backgrounds are in 3DCG. It was decided that this part would be done with Flash, so the background characters were done with Flash models and I kinda drew on top of that. But I don’t feel good without the convergence lines so I drew them here anyways.

How was it working with Flash?

It was the first time I had to draw on top of layouts done with Flash. And of course if you’re going to work at Science Saru, you’re going to have to use it. It felt really new. This time, Yuasa said he wouldn’t use Flash, and that really surprised me: he had gone so far with it on things like Lu Over the Wall, and now he wasn’t using it? But he said something along the lines of “there’s too much talk involved”.

But then for this scene, the background is moving, right? So what were we supposed to do? And naturally, Abel Gongora[11] and one or two other people from Saru who can use Flash came up and split it between themselves: first they modeled the camerawork, and then applied some corrections. Yuasa directly managed all of the Flash process. Then when Yuasa was OK with it, I came and did my own corrections and left the rest to the key animator.

During that concert scene at the end, there’s a fire dragon, right? But it’s CG.

That’s right.

Wouldn’t you have liked to do a 2D Kanada Dragon there? (laughs)

Of course, if there’s a dragon I want to make it a Kanada Dragon! (laughs) But Gongora was entirely in charge of that part. Moreover, Yuasa made pretty detailed instructions for what it should look like: with scales, a real dragon shape, like a sort of huge dragon-like carp streamer. So nothing like a Kanada Dragon (laughs). In the end, it’s fictional, but I think Yuasa didn’t want to completely ditch the reality of that world either.

Did you use any reference footage for the dance scene?

I did use some, but not stuff I filmed myself, rather things I picked up here and there. The dance moves were more-or-less drawn in the storyboards, but I had no idea how to read Yuasa’s storyboards, and of course the key animators didn’t either (laughs).

But as we started submitting our drawings, how do I say this… Yeah, the drawings were done according to the storyboard, but something didn’t feel right. Yuasa hadn’t done any corrections, but I wasn’t sure it was really OK… I decided to leave those there until I came up with something. And you know how Yuasa always uploads these short videos of a monkey dancing on Twitter? I saw that by complete chance, and it clicked. Man, this was it! (laughs)

It was a sort of kick dance, where you move the legs around in all directions. It felt like a sort of indirect call for me to do it myself. So I looked for videos of kick dancing and shuffle dancing and found lots of stuff to use.

There’s a lot of star animators on Inu-Oh, but the drawings and the animation are kinda rough, aren’t they? Wasn’t it hard to be animation director on such a movie?

I think Yuasa knew what he was doing with Inu-Oh. He must have wanted to appeal to a large audience, right? He didn’t use weird angles, did his hardest not to use the deformations he’s so famous for, so that the normal viewer wouldn’t be too weirded out by the pictures. My theory is that he tried to make something easier to watch by unifying the visuals and making them a bit more realistic.

The hardest thing was to maintain the sense of unity of the character designs. The childhood parts were handled by Nakano, and I did the adult parts. But Yuasa was really thinking about how to keep it unified. The animators and the animation directors were all extremely good, but he didn’t want to let them do their own thing because of that: he tried to put it all together as one single movie.

How did you split the parts of the movie between Mr. Nakano and you?

At first, Nakano was animation director for the A part, and from there he moved on to become the chief animation director for the entire childhood part. As for me, I was originally just supposed to animate the bit where the shogun’s wife hides the eclipse with her fan. Since I had done animation there, they asked me to become the animation director for that entire part, and then naturally for the entire adulthood section of the film. I think that’s how it happened.

I’ve heard you got busy with another project in the middle of the production. Is that true?

That’s right. Inu-Oh’s schedule went through many changes… (laughs)

Was it because of Mr. Miyazaki’s movie?

It wasn’t. That film was already over by that point.

Is that so? When I interviewed Toshiyuki Inoue in December 2021, he said that he was still working on it…

I was with Miyazaki from January 2019 to August 2020. So I was already done. After How Do You Live?, I moved to Evangelion 4.0, then on to Inu-Oh.

Oh yeah, Inu-Oh was initially supposed to come out in 2021, wasn’t it?

It was. But in the end it came out in May 2022.

You’ve got a pretty good memory.

Is that so? I kind of have the timeline in my mind. The retakes for Inu-Oh took a lot of time, and then I got busy with Mob Psycho III. I was on multiple things at the same time, so I thought it’d be better to drop from Inu-Oh. Though I still did corrections.

How was it on How Do You Live?

Well, it was my first time working with Miyazaki, so it was really exciting, and… How do I say this… There were only the top names of the industry, people like Akihiko Yamashita, Kitarô Kôsaka, Takeshi Inamura, and Megumi Kagawa, a veteran who’s been supporting Ghibli for a while… I was suddenly in the middle of such incredible people.

So it was a bit like Khara, wasn’t it?

You could say that. I got many opportunities to talk with Yamashita or Kagawa… But the animation director, Takeshi Honda, was sitting right next to Miyazaki so I couldn’t just go talk to him. But sometimes Miyazaki would walk around the studio, and everytime I went “wow, it’s Miyazaki! It’s the real thing!” and then the exact same thing everytime Toshio Suzuki passed by, like they were two big stars.

I see (laughs). Well, we look forward to seeing the film!

Right? Me too!

All our thanks go to Mr. Kameda for his time and kindness, as well as to Ms. Mayo Arita and Ms. Fumie Takeuchi for their collaboration.

Interview by Matteo Watzky and Ludovic Joyet.

Transcript by Karin Comrade.

Introduction, translation and notes by Matteo Watzky.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

Footnotes

[1] Fullmetal Alchemist: The Sacred Star of Milos. 2011 movie, dir. Kazuya Murata, Studio Bones. Spin-off film to the Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood series, notable for its excellent action and effects animation. It was a springboard for a new generation of animators, among which Yoshimichi Kameda, Ken’ichi Kutsuna and Kiyotaka Oshiyama.

[2] Hiroyuki Imaishi (1971-). Animator, director. A major figure of 2000s animation and a chief representative of the “Kanada school” of animation. One of the main artists in studio Gainax’s latter years, he went on to create studio Trigger and, there, has directed cult works such as Kill la Kill, Promare and Cyberpunk: Edgerunners.

[3] The Gutsy Frog. 1972 TV series, dir. Eiji Okabe and Tadao Nagahama, Tokyo Movie. A classic of 1970s animation, considered one of the representative works of studio A Production, where students of legendary animator Yasuo Otsuka formulated many of the basic elements of anime’s visual comedy language.

[4] Yoshinori Kanada (1952-2009). Animator. One of the most important artists in Japanese animation history, who revolutionized mecha, effects, and character animation. Sometimes nicknamed “the father of sakuga”, he was one of the first animators to be widely recognized for his unique style. He has spawned generations of students, from Masahito Yamashita to Hiroyuki Imaishi and Yoshimichi Kameda. Notable works include Invincible Super Man Zambot 3, Galaxy Express 999, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind…

[5] Claire Launay. Animator. French animator now affiliated with Studio WIT. Famous thanks to her graduation film Star Burglar, she has now specialized in character animation, with her chief contributions being on the Ousama Ranking series.

[6] Keisuke Watabe. Animator, character designer. A major figure of Kanada-style animation in the 1990s and 2000s, famous for his work, among others, on Magic Knight Rayearth and the Pazudora series.

[7] Hajime Ningen Gyatorz. 1974 TV series, Tokyo Movie. One of the iconic “A Pro comedies”, well-known not just for the quality of its comedic acting but also for its strange, minimalistic character and art designs.

[8] Taiyô Matsumoto (1967-). Mangaka. One of the major manga artists of the last decades, his most famous work include Tekkonkinkreet and Sunny. He is also well-known for his collaborations with Masaaki Yuasa on Ping Pong and Inu-Oh.

[9] Norio Matsumoto. Animator. One of the most influential artists in the history of anime, he contributed to rewriting the vocabulary of action animation in the late 1990s and early 2000s with a focus on deformation, fluidity, and a heavy inspiration from real-life martial arts techniques. He is particularly famous for his work on the Naruto series.

[10] Atsuko Fukushima. Animator, character designer. Affiliated with studios An Apple and 4°C, she is among the early generation of realist animators in the mid-1980s, alongside her husband Kôji Morimoto and their common master Takashi Nakamura. Notable works include Robot Carnival, Akira and Genius Party.

[11] Abel Gongora. Animator. Spanish animator originally from Ankama and now a member of studio Science Saru, one of the most prominent users of the software Flash in Japan. His short in the anthology Star Wars: Visions contributed to make him better-known to the wider public.

Incredible interview, thank you!

Thanks to you for the kind comment!