On March 15, 2021, studio Ghibli producer Toshio Suzuki announced the death of Yasuo Otsuka at age 89. With him, it is one of the most important figures in world animation that goes away; it is no overstatement to say that Otsuka was the very embodiment of anime and its history.

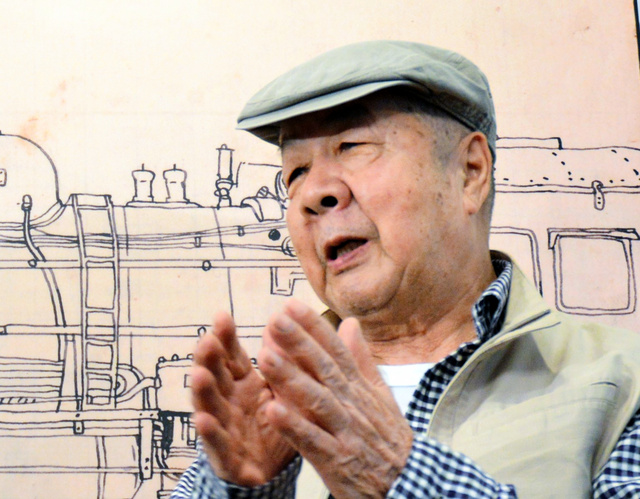

Otsuka was born on July 11, 1931, in the Western prefecture of Shimane. He took a liking to machines as early as the age of 10, when he saw a steam locomotive for the first time. But like most Japanese artists from his generation, his first real encounter with mechanical objects was with the military: in 1945, his family moved next to a military base and he had many opportunities to see, admire and sketch military vehicles. These were foundational experiences for the one who would become one of the inventors of Japanese mechanical animation and a world-renowned Jeep fan. The wonder at how machines just move and their pieces fit together to create a whole, and the need to break them down and reconstruct them in drawings would be the first step in Otsuka’s calling as an artist.

After a few years as an amateur and then professional cartoonist, Otsuka entered the world of animation in 1956, when he entered studio Nichidou at the age of 25. Nichidou quickly became Toei, the first and only major animation studio of the country at the time, and Otsuka was its first official recruit. The studio only had two professional animators at its disposal: Yasuji Mori and Akira Daikuhara. Their most talented student, Otsuka synthesized the attention to detail and realism of Mori with the spontaneity and energy of Daikuhara. It was after passing the studio’s entrance exam and doing some work on their first shorts that Otsuka became a second key animator under Daikuhara on Toei’s first feature-length movie, The White Serpent, in 1958.

Already back then, Otsuka exhibited great talent and the freedom Daikuhara gave to his assistants offered the young man all the opportunities he needed to flourish. It was therefore on The White Serpent that he animated his first masterpiece, the tempest and underwater sequences that constitute part of the climax of the movie. Whereas many scenes of the movie were still awkward, Otsuka managed to impart a formidable sense of life and volume in his own sequence, even though he was working on such a difficult layout involving complex motion in depth and camera movement. He had already mastered the first fundamental of animation that he had learned by reading and copying Western animation manuals: that animating is all about giving the illusion of life. But that was just the beginning, and he would go even further.

After such a good start, Otsuka quickly rose up the ranks of the studio and became a main animator (or first key animator) on Toei’s second feature film, Shounen Sarutobi Sasuke, in 1959. There, he cemented his friendship with Tôei’s other charismatic youngster, Daikichirou Kusube, who had also done his key animation debut on The White Serpent. Starting from then, he was acknowledged as one of the major creative figures of the studio and delivered many standout sequences. From these early days, the most impressive are no doubt the ones from the climax of The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon in 1963: the first Japanese animated work to feature the position of animation director, held by Yasuji Mori, the movie is one of the timeless masterpieces of anime and Otsuka’s sequences, animated and storyboarded in tandem with Sadao Tsukioka, stand as some of the best achievements of the movie.

It would have been no easy work to keep track of the monsters’ many heads as well as the motion of the titular prince; but the two men easily pulled it off in an amazing action scene that’s at the same time frightening, awe-inspiring and full of excitement. There is so much complexity here; and yet, what is the most striking is not the technical tour de force but rather how much emotions the animators gave to their characters, as the young girl crawls in terror and the prince tries his hardest to fight off the beast.

1963 was also the year anime came to television, and Otsuka quickly positioned himself at the vanguard of Toei’s ventures into that new media: in 1964, he was animation director on the studio’s first TV series, Ookami Shounen Ken. This is where he met the ones that would become his two greatest students: Isao Takahata, who was episode director, and Hayao Miyazaki, an in-betweener at the time.

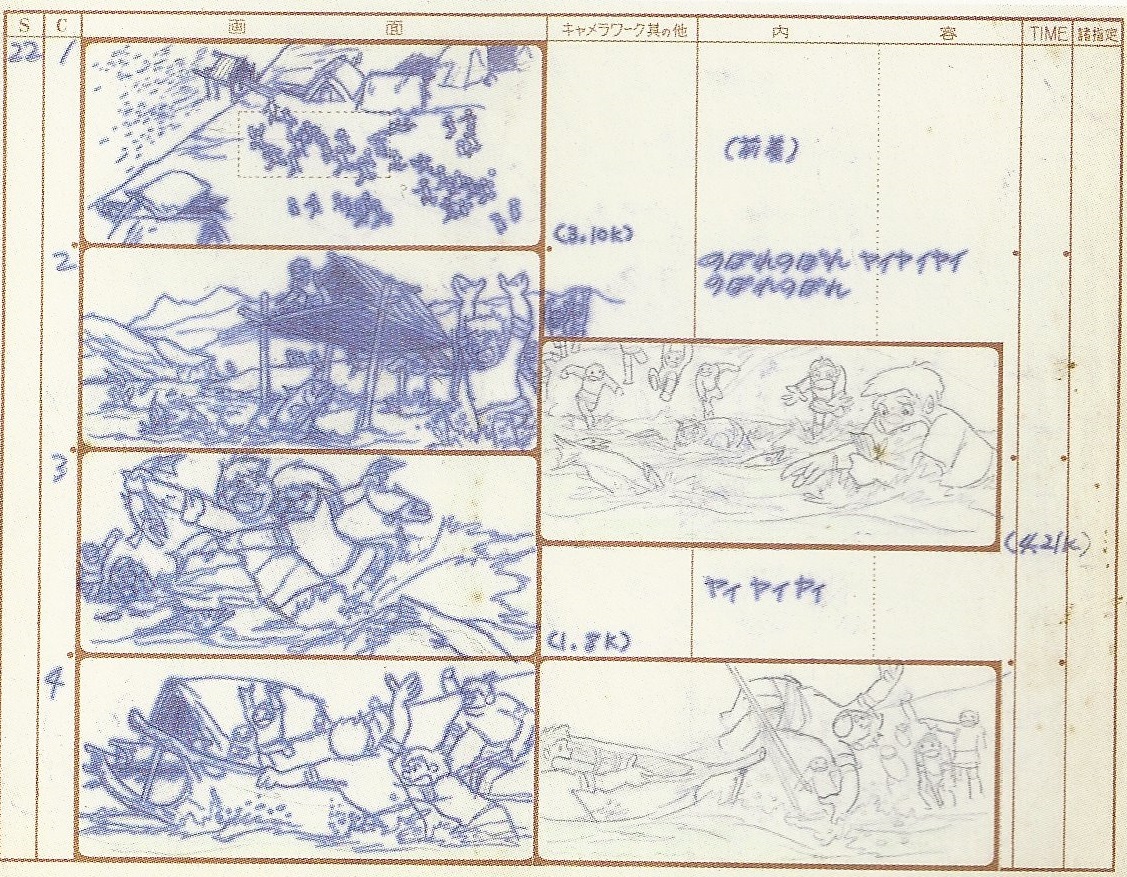

Around 1965, Otsuka was deemed important enough by Toei’s management to be offered the direction of their next feature film. Otsuka, an animator first and foremost, declined and gave the position to the promising young Isao Takahata: the movie would become one of Toei’s greatest masterpieces, Hols, Prince of the Sun. Although it was a long and painful production, Otsuka played a key role as animation director and drew the storyboards on the indications of Isao Takahata. From there, he could directly train the studio’s promising new generation: established figures like Reiko Okuyama and Akemi Ota, but also rising stars such as Yôichi Kotabe and Hayao Miyazaki.

Hols was a revolutionary movie, thanks to its stellar direction and complex themes. From the point of view of animation, it was there that Otsuka contributed to establish one of the most important stylistic features still today associated with anime: framerate modulation. On the end of the movie’s opening scene, Otsuka animated two characters on wildly different framerates and, what is more, used what was considered “limited” animation on one of those: the giant was animated on 3’s and 4’s, meaning that just one frame in 3 or in 4 was a new one. In the context of the scene, it gave weight and magnitude to the motion of the giant, in contrast with Hols’ faster and more dynamic movement. But more than considerably expanding the expressive possibilities of cel animation, introducing framerate modulation gave animators that much more freedom and the ability to break the conventional limits of “full” and “limited” animation in favor of the pure “joy of motion”. This central idea, following which the animation is not just subservient to the action but has a value and a power of its own, is probably the most central and enduring element of Otsuka’s legacy, one that is still carried over by animators today and so-called “sakuga” fans.

Despite being such an artistic achievement, Hols was a commercial failure, and Otsuka was partly blamed for it. Moreover, he felt that he had been replaced in his role of Takahata’s second-in-command by the young and charismatic Hayao Miyazaki. It was then that Otsuka was invited by his longtime friend Daikichirou Kusube to join the newly-created A Production, a subcontracting studio that was already a pillar of the TV anime industry.

Although Otsuka contributed to some TV series in the late 60’s (most notably the iconic opening of Star of the Giants and the controversial 1969 Moomin), what really brought him over to A Pro was a passion project: adapting Monkey Punch’s manga Lupin the Third. There were three things that led Otsuka to this work: a possibility for him to let loose his sensibility towards mechanical animation; an opportunity to leave the stifling atmosphere of Toei for a new, more independant working environment; and a chance, maybe, to pursue Hols’ ambition to make animated movies aimed at an adult audience.

Otsuka began his work on Lupin as key animator on the pilot film, released in 1969; but his real contribution was on the first season of the TV show, in 1972, on which he worked as animation director. When the show’s rating began to drop, it was Otsuka who brought in two new directors just out from Tôei, Isao Takahata and Hayao Miyazaki, who would be able to take it in a new direction. But most importantly, it was from there that Otsuka started training yet a new generation of animators that would take his name as “the Otsuka school”: its most important members were Yoshifumi Kondou, Yuuzou Aoki, Osamu Kobayashi and Tsutomu Shibayama. Some of them would later join studio Ghibli or create structures of their own such as studio Ajia-Dou, established by Kobayashi and Shibayama.

Lupin was no doubt Otsuka’s child, the place where him and his students Yuuzou Aoki and Hayao Miyazaki would be among the first to develop a distinct philosophy of mechanical animation, both realistic and expressive. What this entailed was not just a new approach to drawing and motion, but also the integration of real car and plane models rather than original ones – although it was also there that Miyazaki introduced some of his first iconic airship designs.

Lupin also embodies the best Otsuka’s philosophy: a prodigious sense of fun, a love for machines of any kind, and a passion for motion itself. All these elements were passed down to his best student Hayao Miyazaki, as is visible in the sequence below that the latter animated: Zenigata’s and Fujiko’s shapes are constantly bending, as if the very outlines were about to collapse, just as the characters are constantly on the verge of falling. And yet, there is no impending danger – only a prodigious sense of fun and wonder at the animator’s amazing skill.

After the first Lupin, Otsuka’s career in the 70’s was rich and it would take an entire article to completely do it justice. Suffice it to say that it was rich and full of masterpieces, such as on Panda Kopanda, Future Boy Conan and, of course, one of his greatest works as animation director: The Castle of Cagliostro. It was also then that he did his directorial debut, one of the only works he ever directed: the 1977 movie Sougen no Ko Tenguri. Most importantly, it was in 1978 that Otsuka joined studio Telecom Animation, that had been created in 1975 to take the place of A Pro which had just disbanded. The place was full of newbies, and Otsuka’s talent was sorely needed to help carry on Lupin III Part II that Telecom was animating; it’s probably there that Otsuka fully discovered his own calling as a teacher: he would stay in Telecom for the rest of his life.

Indeed, Otsuka’s last major work as animator would be in 1985, on Sherlock Hound. By then, he had already started passing on his passion for animated motion: for the next 35 years, he would teach and give lectures in places as diverse as Telecom, Toei’s Animation Institute, Yoyogi Animation Academy, Taiwanese and French schools, and studio Ghibli. A complete list of all the men and women he taught would be endless, but among them we find Evangelion’s character designer Yoshiyuki Sadamoto, genius animator Shinji Hashimoto, but also foreign artists such as French animator Ken Arto; and that’s not even starting to include all the ones he inspired without having actually met or taught them.

Otsuka seems to have always been aware of his role in the history of anime, and along with his friends from Ghibli, he always devoted time to retracing the evolution of the art form. He contributed to many books and exhibitions, the most comprehensive one being no doubt his own memoirs, 1983’s Sakuga o Ase Mamire.

Retracing Yasuo Otsuka’s career is simply to retrace the history of modern Japanese animation, from its beginnings to today. It is simply impossible to fully estimate the talent and importance of one of Japan’s greatest animators, and even after his death, his legacy will live on forever. Besides all the masterpieces he produced and geniuses he trained, Otsuka’s greatest discovery was simply the power that lies behind motion. He realized that, beyond any technical aspect, animation has an expressivity of its own, and that the love the individual animator puts into their work always carries over to the viewer. Otsuka’s life and career were probably shaped by one simple thing: passion. Passion for the machines he loved to admire and draw, for the people he met and exchanged with, and passion for his art. This is what makes every one of his works so great, and why he will be remembered for many, many years to come.

It’s nice to read such an homage, so full of passion.

Still, a few factual remarks seem necessary regarding your text :

1) “important enough by Toei’s management to be offered the direction of their next feature film”

This is an information I have never seen mentionned anywhere. It would be precious to know where it comes from.

On the other side, Ôtsuka himself has always told and written he had been offered the responsability ob being the “animation director” of the next feature project, and as such, asked to work hand in hand with a director, of course, as it has always been in Tôei’s production model.

2) “Moreover, he felt that he had been replaced in his role of Takahata’s second-in-command by the young and charismatic Hayao Miyazaki.”

There is probably a misunderstanding here too, as it allows to think there was some frustration on Ôtsuka’s side regarding the role played by Miyazaki on that film. It has never been the case, AFAIK.

3) “When the show’s rating began to drop, it was Otsuka who brought in two new directors just out from Tôei”

This is unexact. Takahata and Miyazaki (and Kotabe) came to A Pro to work on the project to adapt “Pippi Longstocking” into a TV series, and certainly not to work on “Lupin III”. They were already at A Pro for some time when the company’s CEO Fujioka Yutaka suddenly asked them to work on “Lupin”.

4) “created in 1975 to take the place of A Pro which had just disbanded”

This is also wrong, as A Pro has never been disbanded, but just had the company’s name changed in 1976.

5) “it’s probably there that Otsuka fully discovered his own calling as a teacher”

Ôtsuka started to teach animation much earlier, during his work at Toei, where he would always mentor the members of his small group of co-workers, and formally, was teaching once a week at a school named “Tokyo Design College”, as early as in 1968.

6) “Indeed, Otsuka’s last major work as animator would be in 1985, on Sherlock Hound.”

Ôtsuka’s animating work on “Sherlock Hound” has taken place earlier, as it was on episodes directed by Miyazaki, which means they were working on them in 1981-82 (before Miazaki left Telecom). In 1985, Ôtsuka was busy on “Little Nemo”, and if the “Sherlock Hound” is often mentionned along with years “1984-85”, it’s because this was the time when the later completed TV series first aired in Japan. But the animation work on Miyazaki’s episodes was over several years earlier.

7) Ôtsuka’s memoirs, “Sakuga ase Mamire”, was first published as a column in the monthly magazine “Animage” from 1981 on , and later as a book at the end of 1982.

(sorry for the bad English)

Dear Mr. Nguyen,

Thank you for your comment, and for taking the time to correct some of the minor oversights and typos I made!

If you don’t mind, I’ll go over some of the remarks you made.

As for 1 and 2, I take the information from the PhD thesis of a French professor, Marie Pruvost-Delaspre, dedicated to Toei. For Otsuka as a director, her account is unclear: she says that “Otsuka was initially offered to take the lead of the project, something justified by the long time he had already spent at Toei; but he declined and suggested giving the position to Isao Takahata” (my quick translation). It does seem she means direction rather than animation direction. As for the issue with Miyazaki, she cites the documentary The Joy of Motion in which Otsuka clearly expresses some form of regret about not having been able to contribute more. But as Pruvost-Delaspre points out, it might just have been a retrospective form of frustration expressed decades later rather than an objective account of how the production really went.

For 3, you are of course right about Pippi! Although A Pro was already full of ex-Toei people, I always assumed it was Otsuka in particular who invited Takahata, Miyazaki and Kotabe, and who pushed for the first two to take over Lupin. But I have no proof, it’s just speculation since they were all very close!

For the point you made about A Pro, I assumed that A Pro and Shin-Ei were different companies altogether, but I was most probably wrong.

Once again, thank you for reading and commenting!

Sorry, I also forgot an elementary typo : the Prefecture Ôtsuka was born is Shimane.