This article published in the November 1988 edition of Animage focuses on OVA productions, reflecting on their impact on the industry after the fifth year of their appearance. We are happy to present you with a translation of this archived document.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

Year 001 was the experiment era,

Year 002 was the genre definition era,

Year 003 was the era of trial and error,

Year 004 was the maniac era…

Year 005 of the OVA calendar is the era of strategy!

Reflecting on the future of OVA development from all the fine works of this Autumn

The very first OVA to come out was DALLOS II published in December 1983, and we could say that the direction OVA would take was almost decided within the first two years, until November 1985. DALLOS got a start on video series by appointing popular staff (Director Mamoru Oshii, who was at his popularity peak with Urusei Yatsura, as well as Studio Pierrot). BIRTH, in 1984, proved the efficiency of promoting the work using events involving staff and voice actors. The pillars of the OVA industry – manga adaptations and anime spinoffs – were in place, and works such as Genmu Senki Reda, Tatakae!! Ikser I, as well as Megazone 23, were already out, so the Bishoujo mecha approach original to OVA was also established. Even if it did not become a major approach, experimental music videos like Machikado no Meruhen had also been done in 1984.

Until that point, for an OVA, we were talking about a budget of 10 million yen per 10 minutes, which meant 60 million for a 60 minutes work. This was a far higher production value than TV anime, and the situation made the creation of productions with high degrees of accomplishment easier. Unlike TV or feature films, projects emerging from the staff’s side were also more likely to realize, which was also appealing.

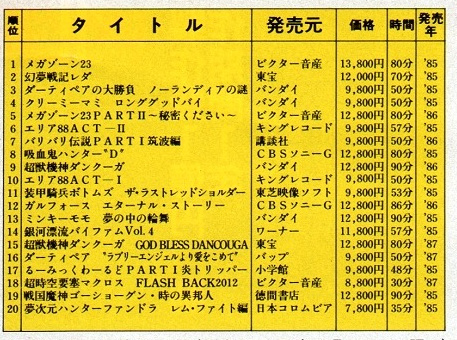

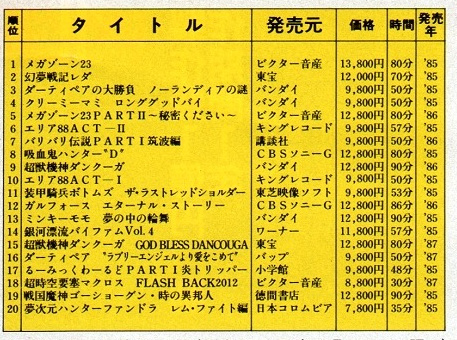

Top 20 OVA sales February 1984 – November 1987 source Oricon

Until that point, for an OVA, we were talking about a budget of 10 million yen per 10 minutes, which meant 60 million for a 60 minutes work. This was a far higher production value than TV anime, and the situation made the creation of productions with high degrees of accomplishment easier. Unlike TV or feature films, projects emerging from the staff’s side were also more likely to realize, which was also appealing.

Top 20 OVA sales February 1984 – November 1987 source Oricon

The influence of overproduction on rental shops

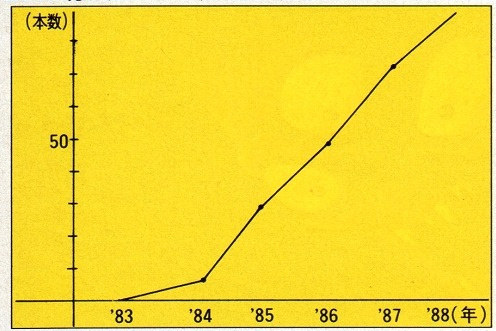

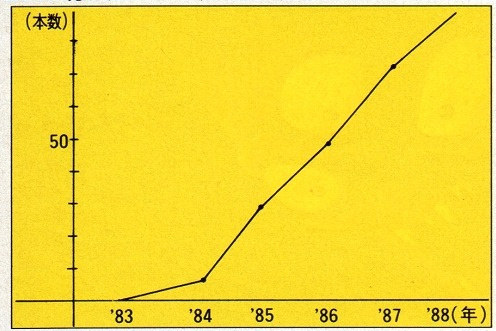

Change in the number of OVA productions (excluding adult works)

As such, the OVA industry was expected to flourish, but instead, it quickly started to stagnate from 1986. The number of works produced grew steadily, from about 50 in 1986 to 72 in 1987 and 90 in 1988. But without a significant growth of the demand, that excess of supply inevitably caused a drop in sales. Without sales, budgets got cut, and original projects were less likely to get approved. The staff for whom most of the work revolved around a handful of popular OVAs were also overworked.

Change in the number of OVA productions (excluding adult works)

As such, the OVA industry was expected to flourish, but instead, it quickly started to stagnate from 1986. The number of works produced grew steadily, from about 50 in 1986 to 72 in 1987 and 90 in 1988. But without a significant growth of the demand, that excess of supply inevitably caused a drop in sales. Without sales, budgets got cut, and original projects were less likely to get approved. The staff for whom most of the work revolved around a handful of popular OVAs were also overworked.

On the other hand, rental video shops were starting to steal the limelight in the meantime. The rental system started in 1984, and already there were 514 official rental shops affiliated to the Japan Video Association, and their number grew every year (respectively 1,818 in 1985, 2,733 in 1986, and 4,732 in 1987), reaching 8,684 in September of this year (based on research by the Video Association). Besides, we estimate the number of non-attached shops at about 5,000, but only by seeing official figures, we can tell how significant this growth was. Even rental fees, which were about 1,500 yen at the beginning, got even more competitive, and now there are even shops which let you borrow for 100 yen. One would say that OVA is a medium for which celluloid is much stronger than film videos, but only a handful of consumers buy OVAs, which cost about 10,000 yen each, and is not a demographic that would suddenly grow. Thus it is not surprising that most makers started to calibrate their production to rental shops. The typical example of that is 1986’s Kizuoibito, which chose to adapt a source material appealing more to ordinary salary-men than to anime fans, with a limited budget compared to OVA standards at the time, and it succeeded.

The apparition of rental shops was also something anime fans welcomed at first since they were now able to easily watch OVAs they could not afford. Yet rental shops did not have as much of them as one would expect, and there were more and more works like Kizuoibito on the market, which differed completely from the type of work fans demanded. Makers’ and staff mentality was also starting to change to creating something valuable and worth spending 10,000 yen to produce, yet something enjoyable enough for a 500 yen fee.

The industry finally reaches maturity

All of this explains why there were very few hits among OVAs from last year to the beginning of this year, and why the future of the industry seemed so uncertain. But from next Autumn to Winter, we are expecting more satisfying works to come out of OVAs than TV and movie theaters. This is not a coincidence. Makers and staff who entered the industry seeing a bonanza were weeded out, and only those with a concrete vision and strategy now remain under the spotlight. The situation of the OVA industry is certainly not rosy, but this establishes a context where creators must rack their brains to survive. Year 005 of the OVA calendar is the era of strategy, and that is the reason why right now, the OVA is interesting.

Demon City Shinjuku, an ambitious OVA which received a movie-level budget and production time. Will it become the savior of the industry!?

100 million yen of budget, One year of production time

It may not have been surprising at the very beginning of the OVA industry, but a work with such a long production time and consequent budget is rare these days. With solid action and a direful setting, Demon City Shinjuku is built as quality entertainment, enjoyable by a broad audience, from kids to adults. It is truly a tour de force, injecting some energy into a declining industry. Behind the production of this work is Wicked City, also adapted from Hideyuki Kikuchi’s original work, directed by Yoshiaki Kawajiri and created by Madhouse. This OVA masterpiece was aimed toward young adults with a 130 million yen budget and two years of production time. It received a broad success, not only sales-wise, but also contributing to improving the public image of Japan Home Video, who endorsed the production. We hear that the movie is a great hit in Hong-Kong, where it is currently screening in movie theaters. There is also much demand for TV broadcasts and sales abroad. A good example of how creating a work of quality with a high budget resulted in increasing the company’s capital.

Interview with director Kawajiri

“My main focus with this work was to create something anyone could enjoy. To do so, I removed all common bad traits of OVA, such as convoluted stories or selfish preconceptions of the creators, thus purely focusing on entertainment. Filmmaking is a composite art, so I wanted for both this and the previous one, Wicked City, to have an organization where we could create elements such as art or music properly, and I think we achieved it for both. Between solidification of the rental business and the total sales hitting the ceiling, it becomes more and more difficult to create ambitious works. Still, I am willing to keep on making OVAs which have nothing to envy of theatrical films.”

Legend of the Galactic Heroes, a low-price long-running series to expand the bottom of the fan demographic

2500 yen, 30 minutes, 26 volumes on a weekly publishing

The number 1 issue for promoting OVA toward the general public was the price. In response, the Legend of the Galactic Heroes series was sold for a reasonable price of 2500 yen each. Kitty Films’ producer Masatoshi Tawara expresses his mind regarding this rate:

“We were able to sell it at this price because it was mail-ordering. By cutting the in-between margins, we were able to lower it to a certain extent. Also, by making it a 26-episode series, each episode was cheaper than making an entirely different story. That also reduced constraints such as advertising expenses or the staff’s binding charges, which were more cost-effective if we made 26 episodes.”

But wasn’t the risk also bigger, particularly in terms of time?

“No, to adapt GinEiDen into anime, even that wasn’t remotely enough. One could say we just had to make it on TV, but this material is not fit for it. It’s difficult to make character merchandise, so we would have struggled to find sponsors, and there were episodes with people talking for 30 entire minutes. To make it on TV, we would have had to change the original work accordingly to add companies or the channel’s directives. Also, we would have gotten less budget. To my mind, the representation of anime will expand by making ‘not easy to translate into anime’ works like this one. Even in the unlikely case that the mail-order system failed, the 26 quality films remaining would be the studio’s fortune. With late-night programs, satellite channels, or CATV, the demand for film content will keep on increasing, so in the long term, I don’t think producing it will be a disadvantage.”

Will the media-mix strategy of Mobile Police Patlabor open the way?

Starting a manga publication in Sunday at the same time as the OVA

The attempt of creating OVA as a part of a media-mix approach existed from the very beginning of the medium, but Patlabor must be the first one to meet equal success on OVA and other mediums, and to do so not as a derived work but as an original one. This Patlabor projected was originally the result of Masami Yuuki, Yu Dezaki, Yutaka Izubuchi, Kazunori Ito and Akemi Takada meeting up, talking about ‘How it would be great if we could create an anime like this,’ and starting to think about it (director Mamoru Oshii participated after the anime production was decided). Yuki-san was not thinking about turning it into manga at first, but when it was decided to create an OVA with Bandai’s participation, he was strongly solicited by the production side to publish a manga in the Weekly Shonen Sunday. This is why the story of the manga is different from the OVA, yet Sunday readers strongly supported it, and it worked as publicity for the OVA. Patlabor was the biggest OVA hit of the first half of the year, and part of it is due to its coordination with Sunday and its 2 million readers.

OVA is like creating an idol

One of the most important factors leading to the success of Patlabor was the reasonable price – 4800 yen for 30 minutes. This was allowed partly because of the mini-series of 6 volumes format, and thanks to the financial contribution of not only Bandai but also Tohoku Shinsha, Pioneer footing the bill for soundtrack creation, the production company making some benefit by inserting a product placement for Fujifilm’s AXIA cassette tape in the middle, etc.… There is, of course, the quality of the work itself, but these mechanisms behind Patlabor’s hit are worth paying attention to. We can also highlight the work of the staff since the low price apparently had a consequence on the budget, yet it does not show. As Bandai’s producer Shin Tsurunosawa puts it: “Personally, I consider it more as a merchandise mix than a media mix. If we consider OVA characters as idols, we can sell recordings, videos, or bromides for each one of them.

In the same way for Patlabor, we can make Gatchapon, erasers, plastic figures, Famicom games, or manga. I think it’s important to expand the image of the work with merchandise like this. Luckily we are a toymaker, so it is easier for us to create derived products like those. I’m willing to keep on pushing this strategy forward.”

We also hear about a new original Patlabor movie project based on the six volumes on its way. If that realizes, it would be the first work to ever come out from the minor league of OVA to the major league of theatrical films. This evolution needs to be followed.

An evolution from the TV series, Ace wo Nerae! 2 brings new feelings on the table

The Dezaki/Sugino duo is back

With the target audience of TV anime becoming more and more juvenile, and because of the lack of original productions, it seems normal for a tired audience as well as staff to be attracted to OVAs. Programs like Kikou Ryuhei Mellowlink, a spinoff to Armored Troopers Votoms, or Ace wo Nerae! 2 may have been broadcast in the golden age of young-adult-oriented TV animation. Ace 2 will condense eight volumes of the source manga into 13 episodes of 30 minutes (equivalent to one season of TV anime), but depending on how it is made, it has enough content to be extended the series on more issues. We could say that by deliberately condensing it in 13 episodes, each one is given a dense, dramatic tension. Expectations are even higher since it is the first in-house work after a long period of co-productions for the Osamu Dezaki (director)/Akio Sugino (animation director) duo. Fans of the TV series are under the charm of Dezaki’s dramatic Gekiga-like direction combining gimmicks like repeated close-ups and transmitted light photography, as well as Sugino’s lively animation direction.

The original Bishoujo Mecha line is still alive!! Top wo Nerae!

This is what happens when you keep looking for bankable things

Producer Toshio Okada says:

“I don’t like the attitude of pretending like you don’t care if it doesn’t sell when producing something. Creating a bankable work, meaning a work producers want is an extremely mature and healthy way of thinking, isn’t it? Bishoujo, Mecha, SF are material the demographic who buys OVA is craving for. If you want to create something that will sell, those three elements are absolutely necessary. There almost haven’t been any OVA using those three properly after Megazone23, though.”

In other words, as Okada-san sees it, the goal was not to focus on girls, mecha, or SF in itself, but to give the staff grandiose themes to be absorbed in, and to let them depict what they want to claim.

“This is the reasoning behind it – I thought that by making the most of the Bishoujo SF Mecha elements, the work would give them more visibility.”

They did not just hire Haruhiko Mikimoto-san for the character designs but also cared about depicting the characters he created cutely onscreen. As for mecha, they chose to make them move well rather than giving them cool designs. And above all, the greatest appeal of this series is its SF-inspired drama.

“It was a very fun work to do, and I am confident about the result.”

Kaze wo Nuke! , a motorbike story about youth proper to OVA

BariDen’s staff pursuing motorbikes once again

Motorbikes meet unchallenged success among the younger generation, yet anime featuring them is unexpectedly rare. It is particularly difficult on TV where sponsors are difficult to attract, and since it evokes gangs (Bousouzoku), the subject is quite delicate. It also requires extreme skills to depict motorbikes realistically. Thus we can say bike stories flourished thanks to OVA, for which viewers are limited and restrictions looser. “There is a motorbike boom right now,” Says director Takahiro Ikegami, “So it’s now or never to make an anime about motorbikes.” He had previously made an OVA about motorbikes called Baribari Densetsu Suzuka-hen, and the project emerged from him and Noboru Furuse-san (co-director on Kaze wo Nuke!, animation director) he met back then, as well as 4-5 bike aficionado staff members talking about making off-road races next time. “Compared to traditional on-road motorbike races, off-road is far more difficult to represent. The ground is uneven so the bike can bounce, and the rider must adapt his posture to reduce that vertical movement. “BariDen was more focusing on drama, so this time we want to let the bike act.”

An unexplored area, Donguri to Yamaneko explores the juvenile literature line

Static drawings unexpectedly work as an appeal

Video companies lately are also trying to target mothers who care about their child’s education by creating OVA versions of Minna no Uta or Nihon Mukashibanashi. Educational videos like these must have a very reasonable price setting, so the production side is also allowed to cut corners. As a result, we cannot guarantee that the last point does not affect the work’s quality. Yet Donguri to Yamaneko takes advantage of the lack of drawings by expressing itself through the charm of each static frame. Animator Yasuhiro Nakura says he wanted to “make a film work that could captivate people even without movement”. Each static frame testifies the amount of effort it required. To draw just one character, he had to put transparent celluloid on the layout, paint it white only on the character and trace the contour with color pencils. The pencils used are water-soluble, so they made the effects by staining it afterward. For the cat, he apparently traced each hair on the cells with a pen. He elaborated this method himself, adapting it according to advice from other staff members. The result is remarkable, and it reminds us that anime is a work by hand.

Manga adaptations with a fixed fanbase assured

More and more adaptations of great manga works

Manga was already the most frequent source material for anime from the very beginning, but in the case of OVA, the runtime is limited to 45-60 minutes, so the main issue becomes how close it can get to the world of the original work. This December, we are expecting the adaptations of Rumiko Takahashi’s One Pound Gospel, pre-published on the Young Sunday and Yoshitoo Asari’s Uchuu Kazoku Carlvinson, pre-published on the Shonen Captain to come out. Anime fans appreciate both, so we are looking forward to the result.

Production companies lead OVA works

It has been five years since OVA appeared. We thought it would soon disappear, yet it exceeded all of our expectations and is now about to evolve into a medium as important as TV and theatrical films.

Yet for OVA, the fact that each volume costs several thousand, sometimes tens of thousands, forced it to develop in completely different ways compared to its counterparts. Some of the interviews we have seen suggested that “People who pay 10,000 yen for one episode of anime are a little bit different from common people. So if we try and adapt to these people’s tastes, it is normal for the content to become maniac-oriented”. That person has a point. But if we only target maniacs, we cannot expect any further development for the OVA industry. And since the medium has expanded so much, the happy era of the first OVAs, where makers could think about maniacs exclusively, is now revolved. The fact that each production company needed to develop its own strategy is a result of that process. The strategy itself can be very particular to each company. For example, to the question ‘Don’t you want to create a tour de force like Demon City Shinjuku?’ one could reply, ‘We would rather create a series instead of one major work.’ Others would decline by saying, ‘Our capital is not sufficient, so such an ambitious work would be too risky.’ Another company would rather turn it into a theatrical film. We could go as far as to say that every one of them had the ‘right answer’ adapted to their situation. The interviews allowed us to highlight the fact that companies’ situations and decisions influenced the color of their production, even more so than we could think by observing the industry from outside.

Yet even if the company’s strategy is successful, I think what truly defines the work’s quality is the passion and competence of the staff members. It often happens that two works handled by the same director absolutely don’t have the same level of quality, and when we look for what made that difference, it is often a matter of staff coordination, fees, or schedule. Whether it is good or bad points, there are always explainable reasons behind it. On a smaller-scale project like OVA (compared to TV or films), those elements are directly reflected in the quality of the final product.

By the way, we often hear that OVA allows less feedback from the audience. In addition to those who buy the material itself, there must be quite a few people watching it by borrowing them in rental shops, yet the industry only gets a handful of reactions. It appears that this is the case not only for magazines but also for the production companies and the staff. OVA’s quality would truly improve only if there is a clear reaction from the audience, particularly for negative feedback, explaining what they found uninteresting and what they would want to see.

That is why I made the deliberate choice of focusing my special edition on the production side’s situation. I am curious to know the point of view of people watching and buying OVA. Please let me know.

I’m looking forward to it.

- Taketomi Yukako

Translation by Nohacro

On the other hand, rental video shops were starting to steal the limelight in the meantime. The rental system started in 1984, and already there were 514 official rental shops affiliated to the Japan Video Association, and their number grew every year (respectively 1,818 in 1985, 2,733 in 1986, and 4,732 in 1987), reaching 8,684 in September of this year (based on research by the Video Association). Besides, we estimate the number of non-attached shops at about 5,000, but only by seeing official figures, we can tell how significant this growth was. Even rental fees, which were about 1,500 yen at the beginning, got even more competitive, and now there are even shops which let you borrow for 100 yen. One would say that OVA is a medium for which celluloid is much stronger than film videos, but only a handful of consumers buy OVAs, which cost about 10,000 yen each, and is not a demographic that would suddenly grow. Thus it is not surprising that most makers started to calibrate their production to rental shops. The typical example of that is 1986’s Kizuoibito, which chose to adapt a source material appealing more to ordinary salary-men than to anime fans, with a limited budget compared to OVA standards at the time, and it succeeded.

The apparition of rental shops was also something anime fans welcomed at first since they were now able to easily watch OVAs they could not afford. Yet rental shops did not have as much of them as one would expect, and there were more and more works like Kizuoibito on the market, which differed completely from the type of work fans demanded. Makers’ and staff mentality was also starting to change to creating something valuable and worth spending 10,000 yen to produce, yet something enjoyable enough for a 500 yen fee.

The industry finally reaches maturity

All of this explains why there were very few hits among OVAs from last year to the beginning of this year, and why the future of the industry seemed so uncertain. But from next Autumn to Winter, we are expecting more satisfying works coming out of OVAs than TV and movie theaters. This is not a coincidence. Makers and staff who entered the industry seeing a bonanza were weeded out, and only those with concrete vision and strategy now remain under the spotlight. The situation of the OVA industry is certainly not rosy, but this establishes a context where creators must rack their brains to survive. Year 005 of the OVA calendar is the era of strategy, and that is the reason why right now, OVA is interesting.

Demon City Shinjuku, an ambitious OVA which received a movie-level budget and production time. Will it become the savior of the industry!?

100 million yen of budget, One year of production time

It may not have been surprising at the very beginning of the OVA industry, but a work with such a long production time and consequent budget is rare these days. With solid action and a direful setting, Demon City Shinjuku is built as quality entertainment, enjoyable by a broad audience, from kids to adults. It is truly a tour de force, injecting some energy into a declining industry. Behind the production of this work is Wicked City, also adapted from Hideyuki Kikuchi’s original work, directed by Yoshiaki Kawajiri and created by Madhouse. This OVA masterpiece was aimed toward young adults with a 130 million yen budget and two years of production time. It received a broad success, not only sales-wise, but also contributing to improving the public image of Japan Home Video, who endorsed the production. We hear that the movie is a great hit in Hong-Kong, where it is currently screening in movie theaters. There is also much demand for TV broadcasts and sales abroad. A good example of how creating a work of quality with a high budget resulted in increasing the company’s capital.

Interview with director Kawajiri

“My main focus with this work was to create something anyone could enjoy. To do so, I removed all common bad traits of OVA, such as convoluted stories or selfish preconceptions of the creators, thus purely focusing on entertainment. Filmmaking is a composite art, so I wanted for both this and the previous one, Wicked City, to have an organization where we could create elements such as art or music properly, and I think we achieved it for both. Between solidification of the rental business and the total sales hitting the ceiling, it becomes more and more difficult to create ambitious works. Still, I am willing to keep on making OVAs which have nothing to envy of theatrical films.”

Legend of the Galactic Heroes, a low-price long-running series to expand the bottom of the fan demographic

2500 yen, 30 minutes, 26 volumes on a weekly publishing

The number 1 issue for promoting OVA toward the general public was the price. In response, the Legend of the Galactic Heroes series was sold for a reasonable price of 2500 yen each. Kitty Films’ producer Masatoshi Tawara expresses his mind regarding this rate:

“We were able to sell it at this price because it was mail-ordering. By cutting the in-between margins, we were able to lower it to a certain extent. Also, by making it a 26-episode series, each episode was cheaper than making an entirely different story. That also reduced constraints such as advertising expenses or the staff’s binding charges, which were more cost-effective if we made 26 episodes.”

But wasn’t the risk also bigger, particularly in terms of time?

“No, to adapt GinEiDen into anime, even that wasn’t remotely enough. One could say we just had to make it on TV, but this material is not fit for it. It’s difficult to make character merchandise, so we would have struggled to find sponsors, and there were episodes with people talking for 30 entire minutes. To make it on TV, we would have had to change the original work accordingly to add companies or the channel’s directives. Also, we would have gotten less budget. To my mind, the representation of anime will expand by making ‘not easy to translate into anime’ works like this one. Even in the unlikely case that the mail-order system failed, the 26 quality films remaining would be the studio’s fortune. With late-night programs, satellite channels, or CATV, the demand for film content will keep on increasing, so in the long term, I don’t think producing it will be a disadvantage.”

Will the media-mix strategy of Mobile Police Patlabor open the way?

Starting a manga publication in Sunday at the same time as the OVA

The attempt of creating OVA as a part of a media-mix approach existed from the very beginning of the medium, but Patlabor must be the first one to meet equal success on OVA and other mediums, and to do so not as a derived work but as an original one. This Patlabor projected was originally the result of Masami Yuuki, Yu Dezaki, Yutaka Izubuchi, Kazunori Ito and Akemi Takada meeting up, talking about ‘How it would be great if we could create an anime like this,’ and starting to think about it (director Mamoru Oshii participated after the anime production was decided). Yuki-san was not thinking about turning it into manga at first, but when it was decided to create an OVA with Bandai’s participation, he was strongly solicited by the production side to publish a manga in the Weekly Shonen Sunday. This is why the story of the manga is different from the OVA, yet Sunday readers strongly supported it, and it worked as publicity for the OVA. Patlabor was the biggest OVA hit of the first half of the year, and part of it is due to its coordination with Sunday and its 2 million readers.

OVA is like creating an idol

One of the most important factors leading to the success of Patlabor was the reasonable price – 4800 yen for 30 minutes. This was allowed partly because of the mini-series of 6 volumes format, and thanks to the financial contribution of not only Bandai but also Tohoku Shinsha, Pioneer footing the bill for soundtrack creation, the production company making some benefit by inserting a product placement for Fujifilm’s AXIA cassette tape in the middle, etc.… There is, of course, the quality of the work itself, but these mechanisms behind Patlabor’s hit are worth paying attention to. We can also highlight the work of the staff since the low price apparently had a consequence on the budget, yet it does not show. As Bandai’s producer Shin Tsurunosawa puts it: “Personally, I consider it more as a merchandise mix than a media mix. If we consider OVA characters as idols, we can sell recordings, videos, or bromides for each one of them.

In the same way for Patlabor, we can make Gatchapon, erasers, plastic figures, Famicom games, or manga. I think it’s important to expand the image of the work with merchandise like this. Luckily we are a toymaker, so it is easier for us to create derived products like those. I’m willing to keep on pushing this strategy forward.”

We also hear about a new original Patlabor movie project based on the six volumes on its way. If that realizes, it would be the first work to ever come out from the minor league of OVA to the major league of theatrical films. This evolution needs to be followed.

An evolution from the TV series, Ace wo Nerae! 2 brings new feelings on the table

The Dezaki/Sugino duo is back

With the target audience of TV anime becoming more and more juvenile, and because of the lack of original productions, it seems normal for a tired audience as well as staff to be attracted to OVAs. Programs like Kikou Ryuhei Mellowlink, a spinoff to Armored Troopers Votoms, or Ace wo Nerae! 2 may have been broadcast in the golden age of young-adult-oriented TV animation. Ace 2 will condense eight volumes of the source manga into 13 episodes of 30 minutes (equivalent to one season of TV anime), but depending on how it is made, it has enough content to be extended the series on more issues. We could say that by deliberately condensing it in 13 episodes, each one is given a dense, dramatic tension. Expectations are even higher since it is the first in-house work after a long period of co-productions for the Osamu Dezaki (director)/Akio Sugino (animation director) duo. Fans of the TV series are under the charm of Dezaki’s dramatic Gekiga-like direction combining gimmicks like repeated close-ups and transmitted light photography, as well as Sugino’s lively animation direction.

The original Bishoujo Mecha line is still alive!! Top wo Nerae!

This is what happens when you keep looking for bankable things

Producer Toshio Suzuki says:

“I don’t like the attitude of pretending like you don’t care if it doesn’t sell when producing something. Creating a bankable work, meaning a work producers want is an extremely mature and healthy way of thinking, isn’t it? Bishoujo, Mecha, SF are material the demographic who buys OVA is craving for. If you want to create something that will sell, those three elements are absolutely necessary. There almost haven’t been any OVA using those three properly after Megazone23, though.”

In other words, as Okada-san sees it, the goal was not to focus on girls, mecha, or SF in itself, but to give the staff grandiose themes to be absorbed in, and to let them depict what they want to claim.

“This is the reasoning behind it – I thought that by making the most of the Bishoujo SF Mecha elements, the work would give them more visibility.”

They did not just hire Haruhiko Mikimoto-san for the character designs but also cared about depicting the characters he created cutely onscreen. As for mecha, they chose to make them move well rather than giving them cool designs. And above all, the greatest appeal of this series is its SF-inspired drama.

“It was a very fun work to do, and I am confident about the result.”

Kaze wo Nuke! , a motorbike story about youth proper to OVA

BariDen’s staff pursuing motorbikes once again

Motorbikes meet unchallenged success among the younger generation, yet anime featuring them is unexpectedly rare. It is particularly difficult on TV where sponsors are difficult to attract, and since it evokes gangs (Bousouzoku), the subject is quite delicate. It also requires extreme skills to depict motorbikes realistically. Thus we can say bike stories flourished thanks to OVA, for which viewers are limited and restrictions looser. “There is a motorbike boom right now,” Says director Takahiro Ikegami, “So it’s now or never to make an anime about motorbikes.” He had previously made an OVA about motorbikes called Baribari Densetsu Suzuka-hen, and the project emerged from him and Noboru Furuse-san (co-director on Kaze wo Nuke!, animation director) he met back then, as well as 4-5 bike aficionado staff members talking about making off-road races next time. “Compared to traditional on-road motorbike races, off-road is far more difficult to represent. The ground is uneven so the bike can bounce, and the rider must adapt his posture to reduce that vertical movement. “BariDen was more focusing on drama, so this time we want to let the bike act.”

An unexplored area, Donguri to Yamaneko explores the juvenile literature line

Static drawings unexpectedly work as an appeal

Video companies lately are also trying to target mothers who care about their child’s education by creating OVA versions of Minna no Uta or Nihon Mukashibanashi. Educational videos like these must have a very reasonable price setting, so the production side is also allowed to cut corners. As a result, we cannot guarantee that the last point does not affect the work’s quality. Yet Donguri to Yamaneko takes advantage of the lack of drawings by expressing itself through the charm of each static frame. Animator Yasuhiro Nakura says he wanted to “make a film work that could captivate people even without movement”. Each static frame testifies the amount of effort it required. To draw just one character, he had to put transparent celluloid on the layout, paint it white only on the character and trace the contour with color pencils. The pencils used are water-soluble, so they made the effects by staining it afterward. For the cat, he apparently traced each hair on the cells with a pen. He elaborated this method himself, adapting it according to advice from other staff members. The result is remarkable, and it reminds us that anime is a work by hand.

Manga adaptations with a fixed fanbase assured

More and more adaptations of great manga works

Manga was already the most frequent source material for anime from the very beginning, but in the case of OVA, the runtime is limited to 45-60 minutes, so the main issue becomes how close it can get to the world of the original work. This December, we are expecting the adaptations of Rumiko Takahashi’s One Pound Gospel, pre-published on the Young Sunday and Yoshitoo Asari’s Uchuu Kazoku Carlvinson, pre-published on the Shonen Captain to come out. Anime fans appreciate both, so we are looking forward to the result.

Production companies lead OVA works

It has been five years since OVA appeared. We thought it would soon disappear, yet it exceeded all of our expectations and is now about to evolve into a medium as important as TV and theatrical films.

Yet for OVA, the fact that each volume costs several thousand, sometimes tens of thousands, forced it to develop in completely different ways compared to its counterparts. Some of the interviews we have seen suggested that “People who pay 10,000 yen for one episode of anime are a little bit different from common people. So if we try and adapt to these people’s tastes, it is normal for the content to become maniac-oriented”. That person has a point. But if we only target maniacs, we cannot expect any further development for the OVA industry. And since the medium has expanded so much, the happy era of the first OVAs, where makers could think about maniacs exclusively, is now revolved. The fact that each production company needed to develop its own strategy is a result of that process. The strategy itself can be very particular to each company. For example, to the question ‘Don’t you want to create a tour de force like Demon City Shinjuku?’ one could reply, ‘We would rather create a series instead of one major work.’ Others would decline by saying, ‘Our capital is not sufficient, so such an ambitious work would be too risky.’ Another company would rather turn it into a theatrical film. We could go as far as to say that every one of them had the ‘right answer’ adapted to their situation. The interviews allowed us to highlight the fact that companies’ situations and decisions influenced the color of their production, even more so than we could think by observing the industry from outside.

Yet even if the company’s strategy is successful, I think what truly defines the work’s quality is the passion and competence of the staff members. It often happens that two works handled by the same director absolutely don’t have the same level of quality, and when we look for what made that difference, it is often a matter of staff coordination, fees, or schedule. Whether it is good or bad points, there are always explainable reasons behind it. On a smaller-scale project like OVA (compared to TV or films), those elements are directly reflected in the quality of the final product.

By the way, we often hear that OVA allows less feedback from the audience. In addition to those who buy the material itself, there must be quite a few people watching it by borrowing them in rental shops, yet the industry only gets a handful of reactions. It appears that this is the case not only for magazines but also for the production companies and the staff. OVA’s quality would truly improve only if there is a clear reaction from the audience, particularly for negative feedback, explaining what they found uninteresting and what they would want to see.

That is why I made the deliberate choice of focusing my special edition on the production side’s situation. I am curious to know the point of view of people watching and buying OVA. Please let me know.

I’m looking forward to it.

- Taketomi Yukako

Translation by Nohacro

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Akira stories – Katsuhiro Otomo and Hiroyuki Kitakubo talk at Niigata International Animation Film Festival 2023

Among the many events taking place during the first Niigata International Animation Film Festival was a Katsuhiro Otomo retrospective, held to celebrate the 45th anniversary of Akira and to accompany the release of Otomo’s Complete Works. All of Otomo’s animated...

“We’re all Iso’s children” – Interview with Ken’ichi Kutsuna [Part 1]

Ken’ichi Kutsuna has always been an alternative figure within the anime industry. A representative member of the “web-generation”, he entered the industry with a training quite different from that of his peers and an affinity for digital animation. After a...

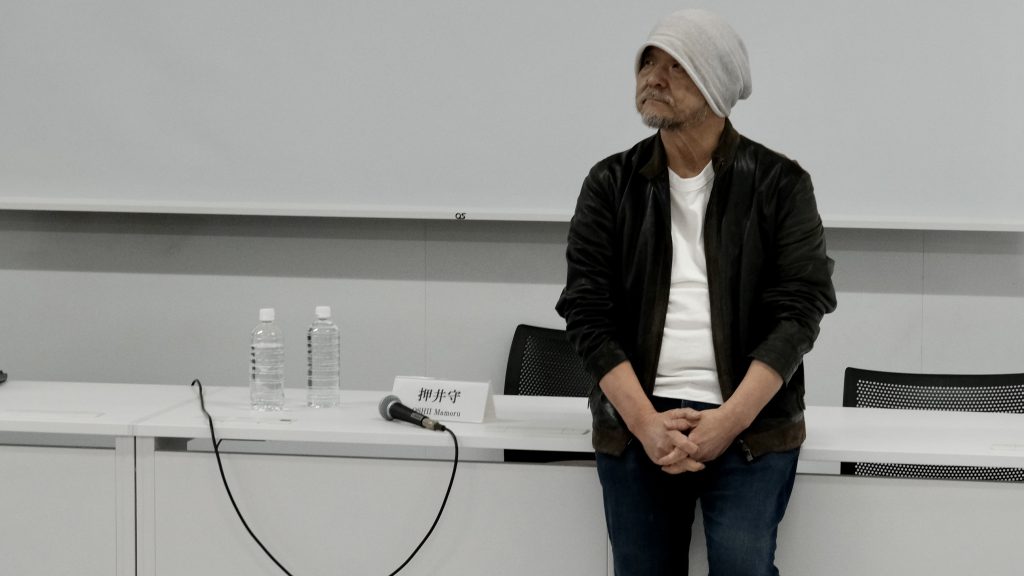

What matters in animation is expression – Interview with Mamoru Oshii [Niigata International Animation Film Festival]

The Niigata International Animation Film Festival held its first edition in March 2023, with a varied program showcasing works from around the world. And to top it off all and start this new festival with style, the head of the festival's jury was none other than...

Hello,

Thank you for the article. It’s nice to see efforts bridging the gap between anime magazines of the past and English-speaking fandom.

At the risk of coming off a little rude, I’d like to point out two things:

1) In the Top wo Nerae section, the text that reads “Producer Toshio Suzuki” appears to be a mistake. Based on the source image, it should read “Producer Toshio Okada” which would be consistent with the text that follows.

2) The text in the Legend of the Galactic Heroes section is missing a preceding paragraph which talks about the low pricing of LoGH relative to other OVAs and introduces comments from Kitty Films producer Masatoshi Tahara. Correspondingly, the quote responding to the potential risk involved with LoGH should be attributed to him.

Best,

Austin

Dear Austin,

thank you for your comment and for pointing out these mistakes, which have now been corrected.

Regarding the section about Ginga Eiyuu Densetsu paragraph, there was a compatibility error: the paragraph appeared on smartphone layouts but not on desktop ones.

Regarding the other mistake, we should have been more careful and check it. Especially since Toshio Okada and Toshio Suzuki aren’t written similarly at all.

Thank you for your kind remarks, we will be more careful in the future.

Best regards,

Dimitri – Chief Editor