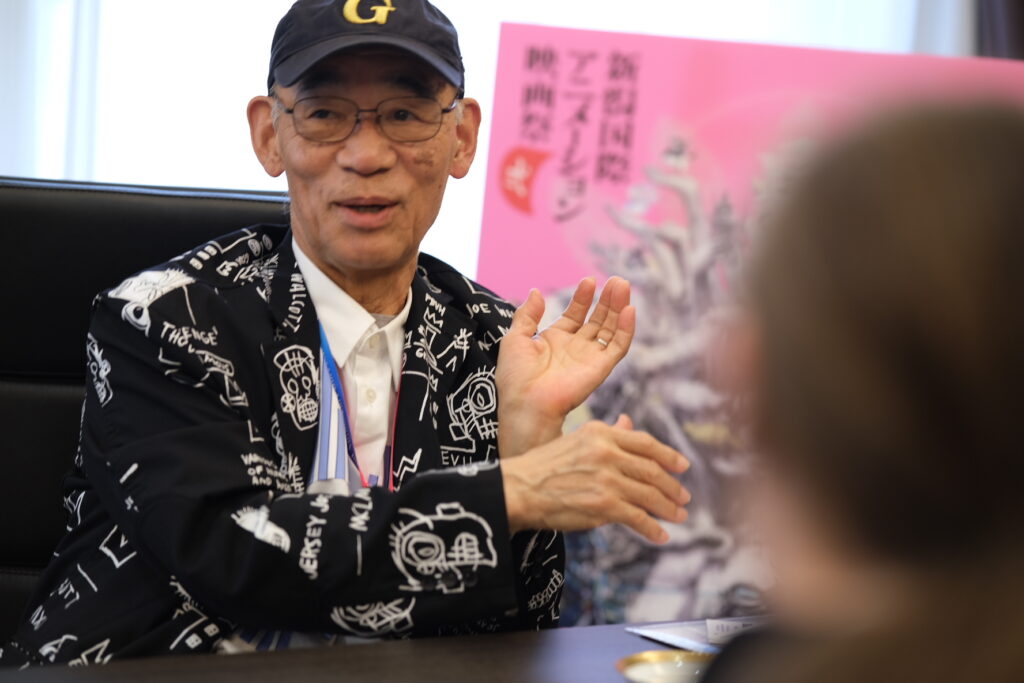

If any animator could be said to have defined the look of Studio Ghibli films in the last 20 years, it would, without a doubt, be Akihiko Yamashita. First only a key animator on Spirited Away in 2001, he was immediately promoted to animation direction on Howl’s Moving Castle in 2004 and then served as animation director and key animator on most of the studio’s productions, be they directed by Hayao Miyazaki, Gorô Miyazaki or Hiromasa Yonebayashi.

Unsurprisingly, this key member of Studio Ghibli was part of the staff of Miyazaki’s latest feature, The Boy and the Heron. As fellow animator Toshiyuki Inoue had told us, Yamashita was one of the key artists on the film, animating the highest number of shots. We were, therefore, extremely curious to talk with him. Not only is Mr. Yamashita an extremely hard-working and talented artist, but he is also full of love for his craft, and it makes reading him all the more interesting.

This interview is brought to you through a partnership with Animeland, France’s first anime and manga magazine

This article would not have been possible without the help of our patrons! If you like what you read, please support us on Ko-Fi!

This interview is available in Japanese. 日本語版はこちらです

“We were a small group of hand-picked people”

What was your reaction when you heard that Hayao Miyazaki was working on yet another “final film”? Were you surprised?

Akihiko Yamashita: I wasn’t. Rather, I was glad to know I’d be able to watch one more film by Miyazaki.

Was it natural for you to join the film once you heard about it? How did you receive the offer in the first place?

Akihiko Yamashita: Around 2016, I did key animation on Miyazaki’s short for the Ghibli Museum, Boro the Caterpillar. I distinctly remember the moment when, after it was done, I visited the studio to greet Miyazaki: that’s when I was first asked to work on the film.

Before that, I had noticed that Miyazaki was drawing all kinds of sketches, and I thought that he might already be working on his next feature… So when I got the offer, I didn’t even wait to know about the story, I immediately said I wanted to be on it. Before that, I had to do some work for two other studios I had engagements with, and once that was done, I transferred to The Boy and the Heron. At that point, I’d say the storyboard was half-completed.

You’ve been working with Miyazaki for around 20 years now. Was there something different this time in terms of studio atmosphere or how it was created?

Akihiko Yamashita: The biggest difference was that we worked without a set release date, so without deadlines.

For nearly every film, the release date is decided sometime during the production, and so it’s common knowledge that once the deadline is set, we’re all heading towards disaster. (laughs) However, with Miyazaki getting old, he couldn’t work as fast as before, so the overall schedule adapted to his pace. We went rather slowly, and the release date was only decided once the film was completed.

On normal films, a lot of staff is gathered and put to work all at once to compensate for the lack of time; this time, we were just a small group of hand-picked people who had all the time we needed. So, if I had to say what made this production special, it’s how quiet it was: everyone followed their own pace, something that you’d never ever meet elsewhere.

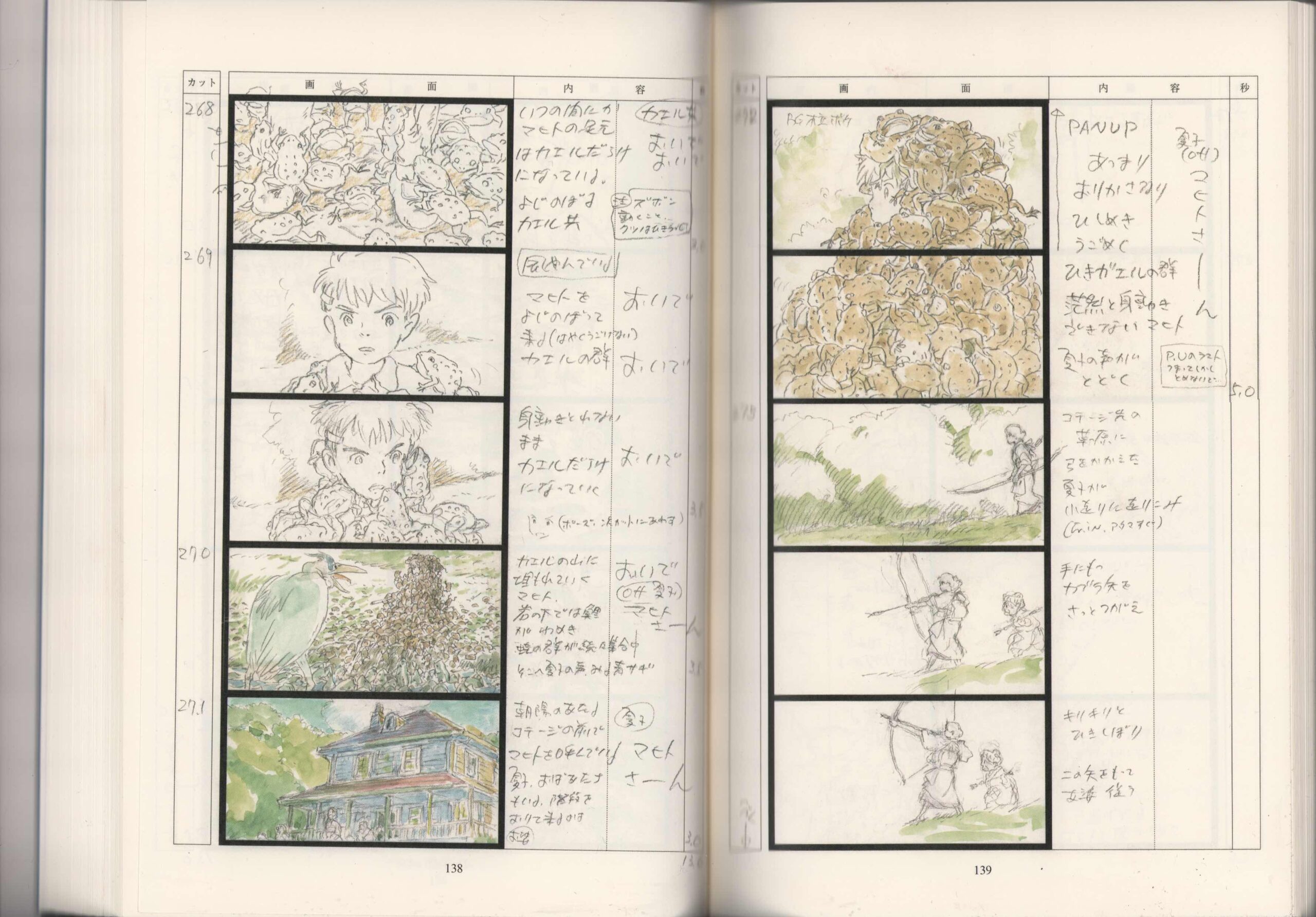

How about the storyboard? Was it different from Miyazaki’s previous ones?

Akihiko Yamashita: As usual, it was quite detailed: you’d never guess how old Miyazaki actually is. That’s not surprising coming from him, but what I just told you about the schedule probably played a part: without any pressure, Miyazaki could wholeheartedly focus on the storyboard and what he expected from the animators. It’s like he went into it without using the brakes once!

Miyazaki’s storyboards are indeed very detailed, but when we talked to Toshiyuki Inoue, he told us the details of the movement and acting aren’t specified that closely. What do you think? Do you manage to express your own style while respecting Miyazaki’s intent?

Akihiko Yamashita: Indeed, the storyboards are detailed but don’t contain that many detailed instructions about the specifics of each movement. It’s the same during meetings: rather than detailed instructions about everything, Miyazaki explains his overall intent, where each scene is supposed to go, and what he expects from us animators. Then, we’re rather free to create our own understanding of all this and do our best to materialize it through animation.

Understanding how far we can understand and realize the directors’ ideas and putting all of our efforts and skill into it, that’s the core of our work as animators. Of course, sometimes we play with the limits and see to which degree we can try out new ideas or techniques without straying too far from the director’s intent. But it’s already hard enough to do things as we’re supposed to, so doing anything more than that is kind of…

“Honda is truly excellent”

What was your reaction when you heard that Takeshi Honda [1] would be animation director?

Akihiko Yamashita: Honda had already been the animation director on Boro the Caterpillar, and most of its staff transferred to the film, so it felt like quite the natural development.

How was the relationship between Mr. Honda and Mr. Miyazaki? Was it different from the one Miyazaki had with his previous animation directors?

Akihiko Yamashita: Honda is best at animating character acting, and he’s become a master of it. Whatever the context, he’ll manage to develop and use that skill. This time, as well, it wasn’t because it was a Ghibli film that he laid that art of his aside and just copied the style of previous films. It seems that caused a few disagreements with Miyazaki…

But in the end, I believe that’s for the best: Honda’s animation brings something different to Ghibli’s animation style, and it has renewed it in a lot of good ways.

How about things in the studio? Was Mr. Honda leading the work? For instance, if you had a question or anything, would you rather go see him or Mr. Miyazaki?

Akihiko Yamashita: For everything that related to characters and their expressions, shadows or the folds of clothing, I systematically referred to Honda’s key animation as a standard. But for the other things which he hadn’t animated himself in his scenes, I drew them in my own way and I think that went without a hitch. Actually, whenever we talked with Honda, it wasn’t really about work but rather small talk!

As I said, the core of an animator’s job is to follow what the director asks, so whenever I had trouble with that, I’d go see Miyazaki to show him my roughs. He’d advise me on the things that were missing and reassure me about those that were good. He really helped me to gain more confidence in myself.

What about the meetings with the animators?

Akihiko Yamashita: As usual, during those, Miyazaki would explain things in an extremely detailed fashion. This time, the production staff transcribed what he said and transmitted it to the entire staff. I read it again, and it was an absolutely fascinating read – it could be made into a book! The storyboard’s been published, and with that, you’ve got a blueprint of the film, but if you had the explanations as well, you would get a detailed commentary of each scene and the intent behind it… But sadly, I don’t think there are any plans for publication.

Did you get any indications regarding your animation?

Akihiko Yamashita: Not really, nothing regarding how I should draw my key animation.

The priority on this film wasn’t the drawings themselves but rather the movement and acting of the characters, so it was alright if the details of the pictures changed from one scene to another. Moreover, in most Miyazaki films, we don’t actually follow the reference materials. The characters grow as the story develops, and the way the drawings evolve alongside the text is what makes working with Miyazaki special. So, the reference drawings always change as well. I suppose you’re going to say that makes our job particularly hard, but it’s actually not the case: we animators also change during the course of the production, and we can draw without thinking too hard about anything because the drawings themselves seem to adapt. Moreover, the viewers themselves don’t really notice when the style changes, so we just need to do animation that works for them.

I’d like to know about how you first met Mr. Takeshi Honda. Was it back when you were both at Atelier Giga?

Akihiko Yamashita: Actually, I believe it wasn’t at Giga, but at the studio Hiroyuki Kitazume[2] had created before that, Studio Pack. We talked about this with Honda a few years ago, and I realized that my memories of it were kinda confused.

Basically, Pack was divided into 2: studio 1 and studio 2, which was further away and where a few of us experienced animators trained 7 or 8 newbie in-betweeners. It seems that Honda was one of them. In the evening, after work, we all ate together in the studio, and we spent that free time chatting and all. Apparently, Honda and I often talked back then, but I have no memories of it…

I know Honda’s right, though, because of this: to decide who would cook the rice, we held a game of rock-paper-scissors, which we called “cook-paper-scissors”, and when I asked Honda about it, he remembered! (laughs) Well, if anything, that shows you can’t trust your own memory…

You served as assistant animation director on The Boy and the Heron, but you’re not credited as such. Why is that?

Akihiko Yamashita: It was decided during the production, and I didn’t take care of that many shots, so that’s why I didn’t get credited for it. Honda left me in charge of multiple shots, but not that many overall, so I wouldn’t say I supervised a lot of the film.

So, was your work as assistant animation director very different from what you did on Ponyo or Marnie?

Akihiko Yamashita: Well, the reason the animation director needs an assistant in the first place is that checking all of the drawings takes time, and if the animation director gets late, it affects the entire production. I was given the position to avoid this, and in that sense, it’s always been the same. It didn’t seem particularly harder or different than usual, either.

Honda’s style is often described as “sharp” and very realistic, but your own animation, like Ghibli’s in general, is softer and rounder. As assistant animation director, did you maybe serve as an intermediary between the two?

Akihiko Yamashita: The animation director is the one to decide on the overall animation style, so as usual, I tried to follow Honda’s orientations.

The work of animators is to follow the animation director: they’re the one who defines what kind of movements, what kind of style they want, and we just have to stick to that. In my case, I had worked with Honda before, so I more-or-less knew what he wanted to go for, but it was more difficult for some of the animators who didn’t know him. So, I’d encourage them whenever I saw they were in trouble.

I precisely wanted to ask about your previous work with Honda. On Evangelion 2:0, did you have any opportunity to watch his drawings and the way he worked?

Akihiko Yamashita: Yes, it was precisely to pay off a debt to him that I worked on Evangelion. He had helped me out many times with my own work, so I told him that it was time for me to do the same.

But I made a fatal mistake… I wanted to draw human beings, but Honda was mechanical animation director, so that meant I’d have to draw robots… And I ended up drawing the fight between the Evas… (laughs)

On my layouts, I sketched rough ideas for the movement, and then Honda drew a lot of additional poses for the fight that I could use as references. Those were absolutely great, so I decided I’d reuse them for personal reference. And so after that, on the Ghibli Museum short Mice Sumo, I redrew Honda’s poses for the sumo fight!

On the other hand, on Up On Poppy Hill and Ponyo, did you have any chance to correct Honda’s drawings?

Akihiko Yamashita: On Up On Poppy Hill, I also assisted the director Gorô Miyazaki, so I supervised pretty much everything. Of course, I could check Honda’s scenes, but I barely had to make any changes to his drawings. He truly is excellent.

“Nothing’s better to draw than a bird”

It seems you were in charge of a lot of shots on The Boy and the Heron. Could you tell us how many?

Akihiko Yamashita: People from the studio told me the number, but I don’t pay a lot of attention to all that, and I forgot… But I just asked again, and they told me it was 360 shots out of the total 1200.

I don’t think I worked faster than I usually do, so I could probably only do that much because the production was so long. If it had been shorter, I’d have done less. But in the end, that’s quite a satisfying number!

On Ponyo and The Wind Rises as well, it’s said that you were in charge of the highest number of scenes. What’s the secret to your speed?

Akihiko Yamashita: First, it seems that I, indeed, draw quite fast.

The other thing is that I can grasp what the director wants rather easily. I don’t lose time thinking too hard about how I should go about producing such or such effect: I immediately start to draw, and as I do, I find the most efficient way to go. I’ve been working in animation for a few decades now, and I’d say I’ve more-or-less got the ropes, so I’ve gotten good at finding shortcuts.

Finally, there’s the fact that I’m very impatient. (laughs)

I’m particularly curious about the heron in The Boy and the Heron. Did you animate it a lot? Did you use any reference for it?

Akihiko Yamashita: I drew the heron a lot, both its exquisite bird form and the old man form. I did use photos as reference for the small details of the face, but I didn’t draw it just as real herons are – or rather, I can’t draw like that. I always insert some deformations when I draw.

Was there anything particularly interesting or difficult in animating the heron?

Akihiko Yamashita: Actually, what I liked the most was animating birds – not just the heron, all the birds.

What I love the most is the wings – when they’re spread out, they always look different, whatever the angle. Sometimes, they’ll look very wide, sometimes thin and very fragile – a bird just has to flap its wings to produce shapes you’ve never seen before. Nothing’s better to draw than a bird. So, while it might be difficult to draw some angles you don’t have a reference for, searching for the right way to draw is interesting in itself – it was the case for the heron and for the pelicans. Though I think I’ve drawn enough pelicans for a lifetime…

Among your scenes, the one that left the strongest impression on me is the confrontation between Mahito and the heron, where all the fish and frogs come out. This scene is pretty terrifying. What was your reaction when you read the storyboard?

Akihiko Yamashita: It’s true that it’s pretty scary.

But I didn’t intend to make it scary when I drew it. I thought that if I drew the frogs and fishes too realistically, it might feel gross to the viewers – actually, I drew it realistically first, and I was the one to feel bad! (laughs) So, I rather approached it as something comical or rather grotesque: I tried to create a completely surreal atmosphere without any connection to reality. That’s how it ended up as scary, I think.

This scene is very slow, almost in slow motion. How did you decide on the timing?

Akihiko Yamashita: I didn’t intend to make it look like slow motion. It’s rather that, when you have so many animals and creatures squirming around at the same time like that, it’s more efficient to slow down the movement. I animated a similar scene once before, and the movement was too fast, so everything felt too light. I had to add in-betweens to slow everything down and make it feel right. Since I had this experience, this time, I could settle on the timing pretty naturally.

Was it difficult to animate so many animals?

Akihiko Yamashita: Crowd scenes are always difficult. But rather than just “difficult”, it’s a psychological issue. You have to be able to endure the weight of so many drawings. This time, all the animals were more or less from the same species, so it was relatively all right. But if they had all been different, then it’d have been a lot more problematic.

“We just have to get to drawing”

I wanted to ask about a specific animator, Shin’ya Ohira[3]. On The Boy and the Heron, he was barely corrected, but I’d like to hear your opinion on his work as a fellow animator and animation director.

Akihiko Yamashita: I believe that the reason Ohira’s scenes on The Boy and the Heron received almost no corrections is because of their special role within the film. Unlike the rest of the film, they’re supposed to look completely nightmarish, and Ohira pulled it off superbly. Ohira is among the people who have an exceptional talent for animation. His work is always interesting.

Actually, one day, I asked him how he decided on the timing for his animation. The answer was that, while he doesn’t do it all by instinct, he never uses an action recorder. Normal people like me, whose skills are still far behind, actually spend most of our days using an action recorder to check our timing and then correct it. So when he said that, I realized that’s how geniuses are.

Were you the one in charge of supervising Ohira’s scene on Howl’s Moving Castle? What was your reaction when you saw his work?

Akihiko Yamashita: Yes, I was the one who corrected Ohira’s drawings on both Howl and Ponoc’s Mary and the Witch’s Flower.

These were some of the best moments in my career as an animation director. It always makes me happy to see key animation with both beautiful pictures and well-made acting. When doing corrections, we draw on top of the key drawings as if we were using tracing paper. If the keys are good, whenever I do corrections, it feels like I’ve gotten good as well! That’s what makes me happy. Of course, my own skills remain the same and I don’t actually improve, but still. (laughs)

Ohira is among the animators who always put me in that state. He doesn’t just come up with poses and expressions I could never imagine by myself, it’s that correcting his drawings is always so instructive. I wish every animator could experience it one day.

At Ghibli, you’ve also participated in works not by Hayao Miyazaki, such as Tales from Earthsea and The Secret World of Arrietty. Did you try to reproduce Miyazaki’s style in such works? If not, how did you manage to go for something different?

Akihiko Yamashita: In any case, I don’t think that anything good comes from just copying someone else.

I’m not that creative, so obviously, I borrow a lot from Miyazaki’s works, but even if I do that, I can’t make up for my lack of ability: my shortcomings will come out in the film anyway, so it’s useless. Moreover, just copying the outer appearance of things is useless: when you’re drawing, you have to think about the intent and the ideas that you’re supposed to convey. It’s only if you’re thinking about these things that you can develop something of your own, find your own style, and make works you can claim as yours.

I see. But what about Ponoc? Since everyone’s from Ghibli, isn’t it hard to create something different?

Akihiko Yamashita: That might be the case, but nobody can reach even a fraction of Miyazaki’s level. So it’s useless to try to copy him – we have to do something individual, something that only we can do, or nothing at all. In that sense, I don’t think we have to think too hard to do something different from Ghibli; we just have to get to drawing.

“That’s what makes animation so fascinating!”

Ghibli’s layouts are often in color. Why is that? Doesn’t it make it harder to draw?

Akihiko Yamashita: I think you’d immediately understand if you saw real layouts, but pictures in black-and-white and pictures in color are completely different things. Ghibli’s layouts aren’t in color because it looks pretty, but because it’s much clearer that way.

Of course, you can perfectly do good layouts with just a black pencil, but it’s difficult and takes more time to work out the details. But if you add color, it takes a lot less time to distinguish between different objects – for example, grass here, water there, metal there… If it’s only black lines, the background art staff who use the layout afterward might have a hard time figuring it all out, thus making their work more difficult. With colors, they can figure it all out in the blink of an eye.

It’s also better for us animators. Colors make it simpler to distinguish between the characters and the backgrounds, and what was initially just lines takes on volume and nuances. In that sense, it’s not difficult at all; quite the contrary, it makes me enjoy my work more.

In all of your work at Ghibli, is there a scene that you like in particular or about which you have particularly strong memories?

Akihiko Yamashita: I can’t say if there’s one I like over the others, but there’s one I remember particularly well.

It was my first work for Ghibli: Chihiro and Haku’s fall in Spirited Away. Miyazaki told me he didn’t want it to be realistic but rather that it should feel like they were floating in their own happiness. I think I was able to realize that to some extent, and it really made me feel that I was working on a feature film to do such a scene.

What about your most difficult scene?

Akihiko Yamashita: Actually, it was only on The Boy and the Heron that I was really confronted with a big difficulty. It’s when the young Kiriko and Mahito get up on the ship. The waves are big and rough, the boat is pitching, it’s all moving against this huge wave that’s coming and there are the characters on top trying to keep their balance.

It wasn’t that hard to draw each element individually, but the difficulty was in putting all of them together. I had to find the good rhythm, the perfect timing through which each of the 4 elements would perfectly complement the others. And I had to convey the right atmosphere for this moment. It really wasn’t easy, but I think I found the right shortcut, and I’m pretty happy about it now.

Finally, is there a scene you’d redo if you could?

Akihiko Yamashita: There are way too many, so I’d better shut up!

There’s one scene in particular I’d like to ask about. That’s in The Wind Rises when Jirô, Castorpp, and Satomi sing together. The way you draw faces is really unique: the characters move, their heads and faces as well, and yet the proportions manage always to remain the same. When you animate such scenes, how do you keep the proportions of the face consistent when everything’s moving?

Akihiko Yamashita: Ah, that’s what makes animation so fascinating!

The proportions remain the same if you watch the sequence as a whole, but if you just look at the keyframes, it’ll look like they’re inconsistent. What makes animation is the optical illusion by which, when the drawings follow each other, the proportions remain the same.

In that sense, my work isn’t about drawing things correctly; it’s rather to find good ways to transform them. It might sound like I’m exaggerating, but I’m not: you can’t just draw by reproducing things as they are. If you do that, you’re not expressing anything anymore.

So, on the scene you mention, but also on any other scene – action or a quiet conversation without a lot of movement – it’s always necessary to bend the shapes to some degree, to make the movement richer. For instance, things like someone’s cheeks, clothes, or any shape can squash and stretch. You could say that you create expression by deforming the parts of a whole in such a way. It’s the same for machines, by the way. People might think that because it’s metal, it can’t change shapes. But as an animator, I’m always looking for new ways to change the shape of every little thing. So I’d be very happy if viewers paid more attention to this kind of thing.

By the way, Ghibli’s characters are often drawn with very few lines. Does that make it more difficult to reproduce certain emotions?

Akihiko Yamashita: It’s not, on the contrary. It’s rather when characters are very detailed that they become difficult to animate. Or, rather than being difficult, the thing is that just drawing a character with a lot of lines would get anyone tired. If you’re so tired of just drawing the character that you can’t draw the most important, that is the emotions and acting, well, it just feels wrong. So, what makes a character design interesting is its ability to be expressive without too many lines. Ghibli characters strike the right balance, and thanks to that, they’re rather easy to animate.

“With Miyazaki, it’s always about expressing something new”

Going back to The Wind Rises, you’ve animated a lot of planes. How was it? Was Miyazaki particularly strict when it came to planes?

Akihiko Yamashita: I just said I loved drawing birds, but actually, I also love drawing planes. In fact, I’d say I love drawing everything that flies.

I wasn’t very interested in biplanes at first, but as I drew more and more, I fell in love with the mechanical and functional beauty of their form. As soon as you get so closely involved with something, you can’t help but appreciate its beauty.

So drawing or animating planes wasn’t difficult – the fun of it always won over. Just like birds, planes never fly completely straight: sometimes they sway around, and sometimes they glide across the sky. For viewers, planes don’t “glide” – it rather feels like they float naturally. But it’s precisely that movement, which seems to defy logic, and how I can reproduce it, that fascinates me so much.

To answer your second question, Miyazaki didn’t give me any particular instructions.

In those plane scenes, you also drew the wind a lot. How do you draw something invisible like the wind?

Akihiko Yamashita: When they draw the movement of human beings, animators become a bit like actors – they try to incorporate what they’re drawing. But they can also do things actors can’t do: that’s giving shape to objects and natural elements. Among those is the wind.

Let’s say hair or clothes are fluttering – you can’t see the wind, but you can express how strong it is through the width of the movement of the hair or clothes. However, to know exactly to what degree the movement is right to express the strength of the wind just as you imagine it, you need a lot of experience. I’ve acquired that experience, and I’d say that I can do it without thinking too hard now.

How about Miyazaki? How does he express such invisible things in his storyboards?

Akihiko Yamashita: When it’s just something like the wind, I try to understand what Miyazaki wants and how strong the wind should be. If he gives specific indications like “strong wind”, I try to follow them to create a feeling of speed. That’s how I decide on the timing. But with Miyazaki, it’s never just about the blowing wind: it’s always about expressing something new, making pictures stronger and stronger.

When you directed The Invisible Man at Ponoc, was your intent to pursue this representation of wind under another shape?

Akihiko Yamashita: Even before starting work on it, before I thought about the story, I wanted to do something about flying. I wanted to create something about the pleasure of flight, but as the plot developed, it turned into something about floating. By “floating”, I mean being taken away by the wind – I wanted to give a shape to the meaning behind that, that is being taken away by one’s emotions. So, I did my best with all the tools I had at my disposal.

You’ve never worked with Isao Takahata. Is there a reason for that?

Akihiko Yamashita: It’s true that we never worked together, and I regret it immensely. The reason is that I arrived too late to be able to work with him.

I had to wait for a long time before my skills allowed me to work on a Ghibli film. I only reached the right level at the time of Spirited Away, and after that, the only opportunity I could have had to work with Takahata would have been on The Tale of Princess Kaguya. Sadly, I was exhausted after The Wind Rises, and I couldn’t participate…

I’ve heard that Takahata was supposed to direct a short on the Modest Heroes anthology. Do you know anything about that?

Akihiko Yamashita: Yes, Takahata was supposed to direct the 4th and final short, but it sadly never happened.

I heard a bit about it, it was supposed to be quite a serious story. I also felt that, visually, it would go further than anything I could imagine – it might have been able to go even further than The Tale of Princess Kaguya had. Sadly, this project vanished, and we’ll never witness it now.

Our heartfelt gratitude goes to Mr. Akihiko Yamashita for his time and kindness.

We wish to thank Fabrice Renaut for arranging this interview, Studio Ghibli’s Nao Amisaki for her availability, and Animeland’s Bruno De la Cruz and Joséphine Lemercier for this partnership.

Interview, translation, introduction, and notes by Matteo Watzky.

Assistance from Dimitri Seraki and Ludovic Joyet.

Notes

[2] Hiroyuki Kitazume (1961-). Animator, character designer. Initially a member of Tomonori Kogawa’s studio Beebow, Kitazume is one of the most iconic character designers of the late 1980’s with his work on Mobile Suit Gundam ZZ and Char’s Counterattack.

[3] Shin’ya Ohira (1966-). Animator. One of the most radical artists in Japanese animation, known for his extremely detailed and expressionist animation. Initially one of the leaders of the realist school in the 1990s, his work now verges on the experimental. He has been a regular presence on Hayao Miyazaki films since Porco Rosso.

If you want to learn more about the topic, you might be interested in:

The following are affiliate links

By clicking on the following links and placing an order, fullfrontal.moe earns a small amount on your order, which helps support the website.

This article would not have been possible without the help of our patrons! If you like what you read, please support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

Oshi no Ko & (Mis)Communication – Short Interview with Aka Akasaka and Mengo Yokoyari

The Oshi no Ko manga, which recently ended its publication, was created through the association of two successful authors, Aka Akasaka, mangaka of the hit love comedy Kaguya-sama: Love Is War, and Mengo Yokoyari, creator of Scum's Wish. During their visit at the...

Ideon is the Ego’s death – Yoshiyuki Tomino Interview [Niigata International Animation Film Festival 2024]

Yoshiyuki Tomino is, without any doubt, one of the most famous and important directors in anime history. Not just one of the creators of Gundam, he is an incredibly prolific creator whose work impacted both robot anime and science-fiction in general. It was during...

“Film festivals are about meetings and discoveries” – Interview with Tarô Maki, Niigata International Animation Film Festival General Producer

As the representative director of planning company Genco, Tarô Maki has been a major figure in the Japanese animation industry for decades. This is due in no part to his role as a producer on some of anime’s greatest successes, notably in the theaters, with films...

Trackbacks/Pingbacks