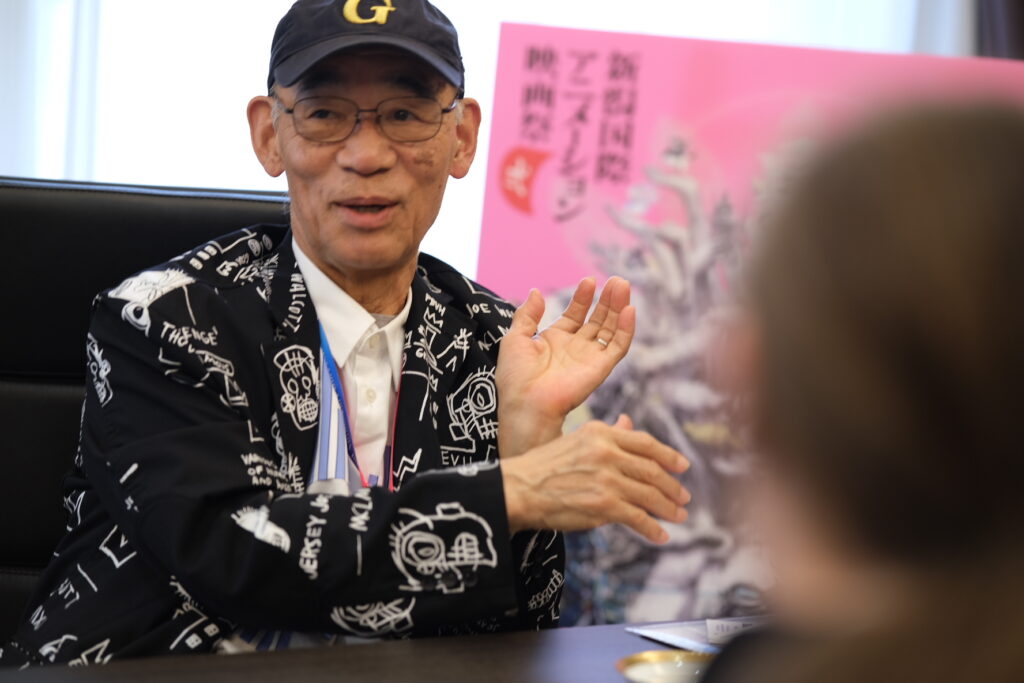

Ken’ichi Kutsuna has always been an alternative figure within the anime industry. A representative member of the “web-generation”, he entered the industry with a training quite different from that of his peers and an affinity for digital animation. After a successful career lasting more than 15 years as an animator and animation director, Kutsuna seems to have moved to the next stage: directing anime openings. His three works so far – Vlad Love, The Fire Hunter and Magical Girls Magical Destroyers – all share common motifs and techniques. We had the opportunity to meet Mr. Kutsuna so that he could explain them, alongside the secrets of his style, in further detail.

This article would not have been possible without the help of our patrons! If you like what you read, please support us on Ko-Fi!

“I just create according to what I feel is the most beautiful”

In your openings, it feels like you’re trying to recreate the feeling of analog photography. Could you tell us a bit more about that?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: There are all kinds of animation, aesthetics, and ways to create pictures… I don’t really discriminate between all of that, I just create according to what I feel is the most beautiful. So it’s not that I’m nostalgic, think that it was better in the old days, or that older is more cool or anything.

I see, so you don’t have a particular attachment for analog photography but just want to recreate the things you like?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: That’s right, the feeling or sense that I think is the most beautiful.

About that, in the dôjinshi where you commented on the Vlad Love opening, you mentioned Princess Mononoke’s influence. Could you explain what you like so much about it?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: Princess Mononoke was made at the time of the switch from analog to digital, and it’s representative of analog techniques at their highest level of development. The first part of the story is particularly beautiful in that sense.

It all comes back to the Covid period when there were some Ghibli revival screenings. I had the opportunity to see Princess Mononoke in the theater again back then, and it was so beautiful! The colors in particular: the red, and green, and black… I realized that these colors aren’t really used anymore. So I just figured I should start using them myself.

Today, it’s not just you who’s trying to revive the analog feel, but also people like Kentarô Waki [1] and China [2]. Is this something like a generational movement?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: We’re not quite from the same generation, so I can’t speak for that, but I do think that there’s an increasing number of people turning back towards old works. It also applies to independent artists like Komugiko2000[3]. I’m already in my 40’s, so I do have some nostalgia towards these older works. However, if younger people like China or Komugiko say that it’s good, I think you can trust them.

Going back to your own work, how do you create that unique feeling? Do you use any software in particular?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: In my case, the background and cels are done the usual way, with the color designer doing their job as usual, for example. But then, before sending it all to the photography, I play with the colors on Photoshop, and then send it.

How about the photography? Who are the people working on it besides you?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: I don’t really have a special person I always work with, but for Vlad Love, I asked the help of Daisuke Matsuki from 10Gauge, whom I’ve known for some time. He’s been doing the photography for the studio’s works, those made by Nobutaka Yoda. So Matsuki did all the photography on Vlad Love, and together we more-or-less narrowed down the kind of processing we wanted through trial-and-error. Since then, I haven’t relied on his help but have tried to reproduce the same processing by asking the regular photography director of a given show I’m working on to aim for the same feeling.

“Within the Japanese animation industry, Kobayashi was like a foreigner”

So that’s how you manage to keep the same style each time even though you’re with different staff?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: I got this way of doing things from the director of Beck, the late Osamu Kobayashi[4]. I asked him how he managed to make things with these specific colors, and he told me he reviewed all the shots with Photoshop. I finally got it then, but by doing that, you’re redoing the work of the background and color designers, so you’re getting involved in things you shouldn’t be involved in. But that was what Kobayashi taught me.

In that sense, you could say that Kobayashi wasn’t really from the industry, but someone who came from outside. Within the Japanese animation industry, he was a bit like a foreigner. So he wouldn’t look down on so-called “web-gen” animators like me but offer us jobs, start doing things on his own, basically never following the prescribed route. That has left a strong impact on me.

Mr. Kobayashi was a genius animator and director, but he also did various events. He would always be there at Animestyle events, lightening up the mood and having fun. Wouldn’t you like to recreate this? Since Mr. Kobayashi is no longer there…

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: Kobayashi made industry events into meeting places, bringing together young animators and veterans. It functioned like a community, and even people from outside the industry would be invited: illustrators and manga artists, musicians, DJs… It’s true that someone has to carry on Kobayashi’s legacy of mixing together all these different cultures.

I’d like to do that myself, but I don’t have all the connections he did, so it’s quite difficult.

Of course, Mr. Kobayashi wasn’t just an MC, he knew a lot about animation… He had been the chairman of the Yoshinori Kanada Fan Club, for example. Today, among animators, aren’t you the most knowledgeable one?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: I wouldn’t say that… My interests are pretty specific, I don’t know as much as Kobayashi did… Also, the older generation has people like Toshiyuki Inoue, who are incredibly knowledgeable as well.

But Yûichirô Oguro told me to call myself an animation researcher, so recently I’ve started to include that in my résumé. It’s a lot of work, but I was nurtured in that culture, and it’s thanks to it that I’m where I am today, so I want to make sure it doesn’t go away.

Going back to Mr. Kobayashi, he’s of course well-known for Beck or Gurren Lagann. What are your memories from these productions?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: At the time of Beck, I was still in university. The first to be scouted by Kobayashi were Ryo-chimo [5] and Yûki Hayashi, who’s been doing character designs at Toei since then, and whom everybody called “Vespa”.

I was really envious, so I tried to join during the summer vacation and only did a few cuts.

The problem was that, back then, everybody thought that animation should only be drawn on paper. I thought that it was a real job, so I did it seriously on paper, and I was very bad at it.

Were you enrolled in an arts college?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: Yes, I was. Nagoya University of Arts and Sciences has a department of visual media and arts, so I enrolled there. I studied everything from photography to film.

Animators who graduated from animation vocational schools often say that they’re not really useful, but how about college?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: It’s been very useful. (laughs) I’m still in contact with some of the teachers, and I even teach there as a part-time lecturer. The artistic education I received there, such as color theory, aesthetics, art theory, and also becoming aware of contemporary art and music has been really important.

I also took general education courses, and I still think that what I learned in the religion and philosophy classes there was very meaningful. I like reading books on philosophy and religion, and it really started with those classes, even though they’d make me sleepy back then.

Who’s your favorite philosopher?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: Deleuze. I can’t remember the title, but there’s this book in which he discusses Godard, and his interpretation of Godard has left a very strong impression on me. Also, among Japanese scholars, there’s Masaya Chiba. Basically, I also like Lévi-Strauss, I like Godard, you could say I like France (laughs).

What are you teaching at university?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: I teach animation, focusing on how to create movement. There are 2 units in a week: one of these I teach myself, and the other is by Yôko Yûki, the artist who was in charge of the second half of the Magical Destroyers opening, and she teaches the students about all the various techniques of expression in animation.

“We’re all Iso’s children”

Another web-gen artist who specialized in openings is Shingo Yamashita [6] . Do you think he’s also influenced by Osamu Kobayashi as you were?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: I don’t think he was as much influenced as me. In his case, I’d say it’s people like Mitsuo Iso [7] or even Makoto Shinkai. He’s been following these people using After Effects and experimenting with new visual trends in real time, so I’d say that what he’s doing has become quite different from my own work now.

Talking about Mitsuo Iso, didn’t you work with him before? At Eddie Mehong’s Studio Yapico.

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: I met Eddie at Satelight, we became friends there as he taught me how to use Flash. Right now, I believe he’s doing NFTs, and I’m thinking that maybe I should try it out as well. But actually I wasn’t really involved with Yapico.

I didn’t meet Iso there, but back when I was in college, I had the opportunity to visit Madhouse. That’s where I saw Mr. Iso for the first time and we talked a bit at that time. Then there were Kobayashi’s events, and when he came we’d have a drink or talk or things like that.

In terms of animation, did you get the Iso shock?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: Yes, I was really struck by his work.

What work in particular?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: I’d say the main ones would be Like the Clouds, Like the Wind and Final Fantasy. These are the two I like best. I don’t think I need to mention episodes 4 and 6 of Gosenzosama Banbanzai. That’s because I love character animation best.

Of course, I discovered him with War in The Pocket… Or no, I think it was Unit 2’s fight in End of Evangelion. Iso’s work became the foundation of both my and Shingo Yamashita’s animation. I’ve been retracing Iso’s works from that time, maybe you could call it copy-pasting… That way it’s possible to create complex movements while saving a lot of time and energy. Now that we’re on digital, a lot of people are doing it. This is especially the case of foreign animators, a lot of them are very good at it. So in a sense, you could say we’re all Iso’s children at this point (laughs).

I believe that, even when he was still drawing on paper, Iso was already thinking digitally. That’s what we talked about with Shingo Yamashita when we first met, and we agreed on what we liked in Iso’s works, so that’s how we became friends. I still remember those conversations.

We’ve been talking about Mitsuo Iso, but doesn’t the foundation for your animation come from Satoru Utsunomiya[8] ?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: I want it to be that way, but recreating the same atmosphere as Utsunomiya is incredibly difficult. So I gave up just following Utsunomiya after some point. I’ve tried to reproduce his genius for so long, but I’ve never had the actual possibility to do so. It was so hard that I just stopped trying. If I thought too hard about it, it would get to the point where I’d be unable to do anything, so it was quite difficult.

Utsunomiya’s work is the ideal of animation and the most beautiful thing there is for me, but it’s really too out of my league.

It’s true that Mr. Utsunomiya’s animation looks really simple and free from the outside, but it’s actually the complete opposite.

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: It’s very delicate, like threading a needle. The posing and the time sheets are very intricate, it’s impossible to reproduce.

Which is your favorite work of his? Obviously, Gosenzosama Banbanzai?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: Gosenzosama is the natural answer, but, let me think… I also like Legend of Crystania. He did a lot of key animation for both the movie and the last episode of the OVA.

Takashi Nakamura’s[9] work on the movie is also fantastic. He animated this sort of fight between a tiger and a lion, and then it’s Utsunomiya’s turn, when a spell is cast and flames burst out in every direction. If you watch it with Utsunomiya in mind, it’s really the best animation there is.

“I only take the jobs where I have complete freedom”

Thank you very much. Let’s go back to talking about your own work. Nowadays, there’s a lot of animators and directors who’re focusing on making openings, right? In your case, why did you decide to go that way?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: I’d say that I reached the limit of what I could do as an animation director. Nowadays, everything has to be perfectly on model and client checks have been getting tougher. But on openings, there still are some directors who are ok letting things be different. I take the job when such conditions are met. But even that is pretty rare, and I just got many opportunities recently. I don’t know for how long that will last.

So the point is basically that you can have complete freedom on openings.

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: I only take the jobs where I have complete freedom.

Does it mean you also like to work on your own?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: I try not to work on my own, actually. The reason is that, if I’m alone, I’ll just slack off. I can’t do that if people are actually waiting for me to do what I have to (laughs).

Usually, how many people do you work with for an opening?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: It depends, as I leave it to the producer from the studio to gather the animation team. I make my storyboards so that they’ll be the same regardless of the quality of the animation. If the animation isn’t good, they don’t have to move, but if I’m lucky with the animators, the storyboard is already strong, leading to an ideal result. Also, I do the editing myself, so I decide where things slow down or speed up, and I touch up the colors. With all that, I try not to be too obsessed with the animation… I try to, at least.

Your openings always use the same motifs, like flowers, water, fish, and so on… Could you explain these?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: Mamoru Oshii told me that you mustn’t spoil everything (laughs). So according to his teachings, I think it’s better to keep the secret. But basically it’s a fetish thing.

Mamoru Oshii had his own dog, so do you own a goldfish?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: Yes, I do. (laughs)

In the Magical Destroyers opening, there’s a goldfish in the second half…

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: It’s not mine. That’s Yûki doing it on her own.

So could you tell us more about her?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: Yûki was actually my university junior. And then on top of that, she went to the Tokyo University of the Arts and studied under Kôji Yamamura[10].

On the opening of Koneko no Chi which I directed, I wanted to have a mix between the CG characters and the work of independent artists, so I called on to her. Her work was fantastic, and she joined the studio I worked at back then, Marza Animation Planet, so we got many opportunities to work together. When the job for Magical Destroyers came, we listened to the song and came to the conclusion that the second half was a perfect fit for her.

So Ms. Yûki was completely free.

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: Yes she was, I didn’t give her any instructions. I knew she’d do something completely different from regular commercial animation, and in the end I think the gap works really well.

How about matching the music and images? Do you have a special method?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: I don’t really start from the storyboard as is usual, but rather I first come up with the motifs I know I’ll use and lay them out on sort of image boards.

Then I edit those to the music and change each shot if the need ever arises. I do that editing with the music, so the length and content of each cut are pretty much defined in the shape of a video-storyboard, and from that point I basically don’t have to change anything anymore.

Which do you think is most important, the pictures or the music?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: Well, music is very important. But I must say I haven’t done like Yamashita, that is, openings with songs by a major artist. I must confess I don’t even get such offers in the first place (laughs). But I feel that if the occasion ever arose, it wouldn’t really fit me. For better or worse, I’m working with relatively minor titles, and that’s how I’m doing.

Is it because you don’t want the animation to lose to the music?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: Not really, I don’t see it as a battle between the visuals and music, it’s more a question of properly understanding the music and the work I’m given and bringing out the best in both. So it’s about how to adjust myself to it.

I guess it’s not a question of likes and dislikes, then. Are you alright with working with a song you don’t like?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: Yes, I’m fine with that. It usually works out.

You have to listen to it over and over again, though.

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: Yes, it’s true that I have to listen to it. Of course, it would be ideal if I could work with music I like. But my kind of music isn’t really big, or rather it’s not the music that would make a good tie-up with an anime. Doing something with music I like is more like a personal dream.

What kind of bands or artists are you thinking about?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: There’s the drummer who plays on Yonezu’s “Kickback”, the opening Yamashita worked for. His name is Shun Ishiwaka and he’s also been working on Blue Giant’s soundtrack. He’s a very successful young drummer on the Japanese scene, and he has this songbook project going on, and he does lots of lives. I’ve tried to approach him but it hasn’t gotten any further. Another artist I love is Kyohei Sakaguchi. I’ve talked to him at one of his lives, saying I’d love to do an animated music video for him, but I have my hand fulls at the moment so it hasn’t advanced either.

Do music videos require a lot of money to make?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: If I work for free, I can make it pretty cheap. I can use a lot of techniques outside of what’s done in the anime industry, so I can put out something qualitative while keeping the costs down, if need be. At university, I learnt about all the methods they use in independent animation: clay, stop motion, CG, rotoscope, collage, live-action… you name it. So it’s hard to say precisely how much it’d cost me.

That’s cool (laughs). How much does it cost for a normal music video?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: Of course, it depends on the people. But if we say the song is around 3 minutes long, that would be about 4 million yen. I could do something without any problem for 3 million. Not a lot, right? With around 6 million, it would feel like too much. But with big artists, it can go up as high as 10 or 20 millions, I believe. Though it’s not like I’ve ever handled that much money (laughs).

But personally, I like low budgets. It leads you to make new discoveries. But to be clear, I’m not saying you should make something for no money!

So it all comes back to Osamu Kobayashi’s influence, doesn’t it?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: That’s part of it. If you can do something on your own, like an independent artist, you don’t have to think about anything other than recouping your own costs. I’ve been watching Kobayashi do pretty much everything by himself all this time, so it certainly influenced me.

Also, I think it’s fun to try finding ways to gather money. Especially nowadays with crowdfunding.

Regarding crowdfunding, you worked on the crowdfunded music video Back to You made by the Animators Dormitory Project, right? Could you tell us how that happened?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: I have a long-standing relationship with The Animator Dormitory Project and the Animator Supporters organization.

Since before the MV, I was teaching for multiple years in an online seminar for them alongside Shintarô Michishita. In that process, the association acquired lots of experience on how to gather money through crowdfunding… Since their goal is to find some sort of solution to the low wages for animators, they decided to generate work for animators with higher unit prices, with the money they had gathered themselves. That’s how that MV was born.

It was your first character design job, right?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: It was the first time I did my own characters on an original and on that scale. But I had done so before for a manga adaptation, the Hori-san to Miyamura-kun OVA.

How do you like design work?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: I love it. It’s a fun job.

On Vlad Love or The Fire Hunter, did you often meet or talk with Mamoru Oshii?

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: We only met twice. The first time was the preparatory meeting for the Vlad Love opening, and then once the opening was done, for delivery.

The first time, he said “in all my career, I’ve never had a bad opening, so I trust you to not fail me this time either. But do it as you like”. And after that he left for a karate lesson or something. And we didn’t have any other real meetings.

Mr. Oshii also loves French cinema, it’s a pity you couldn’t talk more.

Ken’ichi Kutsuna: We barely talked on that first meeting, but we had a long discussion the second time.

I kind-of went all-out, and the client wasn’t sure about it, but Oshii said it was completely all right and that we should go with it as is. For example, there’s this bit where I put red letters on top of red clothes, and even I thought it might be difficult to see, but Oshii said it wasn’t necessary to change anything. He backed me up all the way, and that really moved me.

Then he asked about me, and I told him I was Satoru Utsunomiya’s disciple. Then the dots seem to have connected in his head. He asked me about Utsunomiya, and we talked about him and everything…

Then it was a positive encounter in the end. Thank you for the beautiful story.

All our thanks go to Mr. Kutsuna for his time and kindness, and to Mr. Takahashi for the introduction.

Interview by Matteo Watzky and Ludovic Joyet.

Transcription by Antoine Jobard.

Translation by Antoine Jobard and Matteo Watzky.

Introduction and notes by Matteo Watzky.

Footnotes

[1] Kentarô Waki (1989-). Photographic director. One of the most famous photography directors in the anime industry today, he became famous for his work on the Sword Art Onlineseries. His use of digital effects is instantly recognizable. In recent months, he recreated the cel look of the movie Char’s Counterattackin a PV for the mobile game UC Engage.

[2] China (1996-). Animator. Famous for his work on the Yama no Susumeseries, this young animator recently directed the short Detarame na Sekai no Melodrama, part of the TOHO animation Music Films project.

[3] Komugiko2000. Animator, Illustrator. Independent animator, famous for their MVs with famous groups such as Zutomayo.

[4] Osamu Kobayashi (1964-2021). Animator, illustrator, director. One of the most original artists working in Japanese animation in the 2000s, he contributed to make the “web generation” enter the industry on works such as BECK or Paradise Kiss.

[5] Ryo-Timo (1979-). Animator and character designer, considered to be one of the central figures of the “web-generation” movement of the mid-2000’s. His most famous works are the Tetsuwan Birdy: Decodeand Yozakura Quartet series.

[6] Shingo Yamashita (1987-). Animator, character designer, director. One of the chief representatives of the “web generation” in Japan. In recent years, he has distinguished himself for the openings he directed on major series such as Jujutsu Kaisen, Ousama Rankingand Chainsaw Man.

[7] Mitsuo Iso (1966-). Animator, director. One of the most important animators in recent anime history, Iso was one of the major figures in the realist movement thanks to his incredibly lifelike work. He has since then moved on to direction with SF series such as Dennô Coil and The Orbital Children.

[8] Satoru Utsunomiya (1959-). Animator. One of the leaders of the realist school of animation, famous for his realistic and dynamic style. His work as character designer and animation director on the OVA Gosenzosama Banbanzai!sent shockwave throughout the anime industry when it came out.

[9] Takashi Nakamura (1955-). Animator, director. Arguably the leader of the realist school as it developed in the 80s. As a very popular animator and the animation director of Akira, he directly taught or inspired most of the realist group, including Toshiyuki Inoue and Satoru Utsunomiya. He has since then moved on to become a director and is most famous for A Tree of Palme, Fantastic Children, and The Picture Studio.

[10] Kôji Yamamura (1964-). Animator, director. One of the most important independent animators in Japan, famous for Mt. HeadDozens of Norths. He teaches at one of the most important art universities in Japan, the Tokyo University of the Arts.

Did you like this interview? Help us fund part 2 by making a donation!

You might also be interested in

Oshi no Ko & (Mis)Communication – Short Interview with Aka Akasaka and Mengo Yokoyari

The Oshi no Ko manga, which recently ended its publication, was created through the association of two successful authors, Aka Akasaka, mangaka of the hit love comedy Kaguya-sama: Love Is War, and Mengo Yokoyari, creator of Scum's Wish. During their visit at the...

Ideon is the Ego’s death – Yoshiyuki Tomino Interview [Niigata International Animation Film Festival 2024]

Yoshiyuki Tomino is, without any doubt, one of the most famous and important directors in anime history. Not just one of the creators of Gundam, he is an incredibly prolific creator whose work impacted both robot anime and science-fiction in general. It was during...

“Film festivals are about meetings and discoveries” – Interview with Tarô Maki, Niigata International Animation Film Festival General Producer

As the representative director of planning company Genco, Tarô Maki has been a major figure in the Japanese animation industry for decades. This is due in no part to his role as a producer on some of anime’s greatest successes, notably in the theaters, with films...

Recent Comments